Crystal Palace Company

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Core Strategy

APPENDIX 2 AREA PEN PORTRAITS 1 Beckenham Copers Cope & Kangley Bridge 2 Bickley 3 Bromley Common 4 Chislehurst 5 Clock House, Elmers End & Eden Park 6 Cray Valley, St Paul's Cray & St. Mary Cray 7 Crofton and Farnborough 8 Crystal Palace, Penge & Anerley 9 Hayes 10 Keston 11 Mottingham 12 Shortlands, Park Langley & Pickhurst 13 West Wickham & Coney Hall Places within the London Borough of Bromley Ravensbourne, Plaistow & Sundridge Mottingham Beckenham Copers Cope Bromley Bickley & Kangley Bridge Town Chislehurst Crystal Palace Cray Valley, St Paul's Penge and Anerley Cray & St. Mary Cray Shortlands, Park Eastern Green Belt Langley & Pickhurst Clock House, Elmers Petts Wood & Poverest End & Eden Park Orpington, Ramsden West Wickham & Coney Hall & Goddington Hayes Crofton & Farnborough Bromley Common Chelsfield, Green Street Green & Pratts Bottom Keston Darwin & Green Belt Biggin Hill Settlements Reproduced by permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of HMSO. © Crown copyright and database 2011. Ordnance Survey Licence number 100017661. BECKENHAM COPERS COPE & KANGLEY BRIDGE Character The introduction of the railway in mid-Victorian times saw Beckenham develop from a small village into a town on the edge of suburbia. The majority of dwellings in the area are Victorian with some 1940’s and 50’s flats and houses. On the whole houses tend to have fair sized gardens; however, where there are smaller dwellings and flatted developments there is a lack of available off-street parking. During the later part of the 20th century a significant number of Victorian villas were converted or replaced by modern blocks of flats or housing. Ten conservation areas have been established to help preserve and enhance the appearance of the area reflecting the historic character of the area. -

Walks Programme: July to September 2021

LONDON STROLLERS WALKS PROGRAMME: JULY TO SEPTEMBER 2021 NOTES AND ANNOUNCEMENTS IMPORTANT NOTE REGARDING COVID-19: Following discussions with Ramblers’ Central Office, it has been confirmed that as organized ‘outdoor physical activity events’, Ramblers’ group walks are exempt from other restrictions on social gatherings. This means that group walks in London can continue to go ahead. Each walk is required to meet certain requirements, including maintenance of a register for Test and Trace purposes, and completion of risk assessments. There is no longer a formal upper limit on numbers for walks; however, since Walk Leaders are still expected to enforce social distancing, and given the difficulties of doing this with large numbers, we are continuing to use a compulsory booking system to limit numbers for the time being. Ramblers’ Central Office has published guidance for those wishing to join group walks. Please be sure to read this carefully before going on a walk. It is available on the main Ramblers’ website at www.ramblers.org.uk. The advice may be summarised as: - face masks must be carried and used, for travel to and from a walk on public transport, and in case of an unexpected incident; - appropriate social distancing must be maintained at all times, especially at stiles or gates; - you should consider bringing your own supply of hand sanitiser, and - don’t share food, drink or equipment with others. Some other important points are as follows: 1. BOOKING YOUR PLACE ON A WALK If you would like to join one of the walks listed below, please book a place by following the instructions given below. -

Grasmere Court, Westwood Hill, London, SE26 £325,000 - £350,000 £350,000 Leasehold

Grasmere Court, Westwood Hill, London, SE26 £325,000 - £350,000 £350,000 Leasehold Share of freehold ( Extended lease Modern fitted kitchen length ) Contemporary three piece bathroom Two double bedrooms suite Purpose built apartment Separate W/C Bright and spacious throughout Free off street parking Excellent decorative order throughout Short walk to Crystal Palace Park 2, Lansdowne Road, Croydon, London, CR9 2ER Tel: 0330 043 0002 Email: [email protected] Web: www.truuli.co.uk Grasmere Court, Westwood Hill, London, SE26 £325,000 - £350,000 £350,000 Leasehold Vendor Comments: "When I began my property search (over 14 years ago), I quickly realised that I couldn’t afford a two bedroom flat in North London. Having explored a few areas in South London, I found my dream flat on the borders of Lewisham, Southwark and Bromley. The flat has two double bedrooms, two storage cupboards, a nice sized lounge and kitchen. It was redecorated (painting/new laminate floors) in Nov 19, while the kitchen was renovated in the summer of 2017. There is access to a communal garden that is shared with Torrington Court but if you fancy larger green spaces, a maze, dinosaurs and a lake, then Crystal Palace Park is a 10min walk. If you fancy somewhere more quieter, then Wells Park and Dulwich Woods are close by. The location is fantastic as there are great transport links, which makes commuting for work or social events really easy. There are several mainline stations that are either a 10-15 min walk or a bus ride away. These are Sydenham & Penge West (for London Bridge, East & West Croydon, Victoria and Highbury & Islington), Crystal Palace (Highbury & Islington, Beckenham Junction, West Croydon, Clapham Junction and Victoria), Sydenham Hill & Penge East (Victoria, Herne Hill and Blackfriars). -

Appendix B List of Site Applicable to the PSPO. All Carriageways

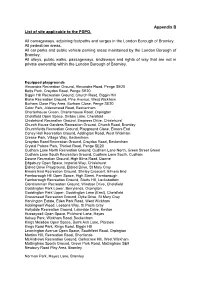

Appendix B List of site applicable to the PSPO. All carriageways, adjoining footpaths and verges in the London Borough of Bromley. All pedestrian areas. All car parks and public vehicle parking areas maintained by the London Borough of Bromley. All alleys, public walks, passageways, bridleways and rights of way that are not in private ownership within the London Borough of Bromley. Equipped playgrounds Alexandra Recreation Ground, Alexandra Road, Penge SE20 Betts Park, Croydon Road, Penge SE20 Biggin Hill Recreation Ground, Church Road, Biggin Hill Blake Recreation Ground, Pine Avenue, West Wickham Burham Close Play Area, Burham Close, Penge SE20 Cator Park, Aldersmead Road, Beckenham Charterhouse Green, Charterhouse Road, Orpington Chelsfield Open Space, Skibbs Lane, Chelsfield Chislehurst Recreation Ground, Empress Drive, Chislehurst Church House Gardens Recreation Ground, Church Road, Bromley Churchfields Recreation Ground, Playground Close, Elmers End Coney Hall Recreation Ground, Addington Road, West Wickham Crease Park, Village Way, Beckenham Croydon Road Recreation Ground, Croydon Road, Beckenham Crystal Palace Park, Thicket Road, Penge SE20 Cudham Lane North Recreation Ground, Cudham Lane North, Green Street Green Cudham Lane South Recreation Ground, Cudham Lane South, Cudham Downe Recreation Ground, High Elms Road, Downe Edgebury Open Space, Imperial Way, Chislehurst Eldred Drive Playground, Eldred Drive, St Mary Cray Elmers End Recreation Ground, Shirley Crescent, Elmers End Farnborough Hill Open Space, High Street, Farnborough -

South Camberwell Southwark Ward Profiles Ward

Southwark Ward Profiles South Camberwell Ward People & Health Intelligence Section Southwark Public Health October 2017 Please cite as: Southwark Ward Profiles. Southwark Council: London, 2017. South Camberwell Ward Profile This profile has been developed as part of the Southwark Joint Strategic Needs Assessment (JSNA). Profiles have been developed for each of the electoral wards in the borough and provide information on a number of topic areas, including: demographics, children and young people, health outcomes, and the wider determinants of health. Due to the limited availability of timely and robust data at an electoral ward level the profiles are only intended to provide a high level overview of each ward. More detailed information on specific topic areas is available through the detailed health needs assessments. We aim to further develop the profiles over time and welcome your comments and suggestions on information you would find useful. Contact us at: [email protected] Key Findings Demographics n Latest population estimates show that 13710 people live in South Camberwell ward n South Camberwell has a total BAME population of 44% n Life expectancy for males in South Camberwell is 83 years of age n Life expectancy for females in South Camberwell is 85 years of age Children & Young People n 23% of dependant children under the age of 20 in South Camberwell ward are living in low income households n There were 695 A&E attendances per 1,000 children aged between 0-4 years in 2012/13 - 2014/15 n 15% of children measured in -

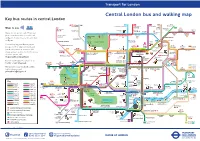

Central London Bus and Walking Map Key Bus Routes in Central London

General A3 Leaflet v2 23/07/2015 10:49 Page 1 Transport for London Central London bus and walking map Key bus routes in central London Stoke West 139 24 C2 390 43 Hampstead to Hampstead Heath to Parliament to Archway to Newington Ways to pay 23 Hill Fields Friern 73 Westbourne Barnet Newington Kentish Green Dalston Clapton Park Abbey Road Camden Lock Pond Market Town York Way Junction The Zoo Agar Grove Caledonian Buses do not accept cash. Please use Road Mildmay Hackney 38 Camden Park Central your contactless debit or credit card Ladbroke Grove ZSL Camden Town Road SainsburyÕs LordÕs Cricket London Ground Zoo Essex Road or Oyster. Contactless is the same fare Lisson Grove Albany Street for The Zoo Mornington 274 Islington Angel as Oyster. Ladbroke Grove Sherlock London Holmes RegentÕs Park Crescent Canal Museum Museum You can top up your Oyster pay as Westbourne Grove Madame St John KingÕs TussaudÕs Street Bethnal 8 to Bow you go credit or buy Travelcards and Euston Cross SadlerÕs Wells Old Street Church 205 Telecom Theatre Green bus & tram passes at around 4,000 Marylebone Tower 14 Charles Dickens Old Ford Paddington Museum shops across London. For the locations Great Warren Street 10 Barbican Shoreditch 453 74 Baker Street and and Euston Square St Pancras Portland International 59 Centre High Street of these, please visit Gloucester Place Street Edgware Road Moorgate 11 PollockÕs 188 TheobaldÕs 23 tfl.gov.uk/ticketstopfinder Toy Museum 159 Russell Road Marble Museum Goodge Street Square For live travel updates, follow us on Arch British -

Bromley May 2018

Traffic noise maps of public parks in Bromley May 2018 This document shows traffic noise maps for parks in the borough. The noise maps are taken from http://www.extrium.co.uk/noiseviewer.html. Occasionally, google earth or google map images are included to help the reader identify where the park is located. Similar documents are available for all London Boroughs. These were created as part of research into the impact of traffic noise in London’s parks. They should be read in conjunction with the main report and data analysis which are available at http://www.cprelondon.org.uk/resources/item/2390-noiseinparks. The key to the traffic noise maps is shown here to the right. Orange denotes noise of 55 decibels (dB). Louder noises are denoted by reds and blues with dark blue showing the loudest. Where the maps appear with no colour and are just grey, this means there is no traffic noise of 55dB or above. London Borough of Bromley 1 1.Betts Park 2.Crystal Palace Park 3.Elmstead Wood 2 4.Goddington Park 5.Harvington Sports Ground 6.Hayes Common 3 7.High Elms Country Park 8.Hoblingwell Wood 9.Scadbury Park 10.Jubilee Country Park 4 11.Kelsey Park 12.South Park 13.Norman Park 5 14.Southborough Recreation Ground 15.Swanley Park 16.Winsford Gardens 6 17. Spring Park 18. Langley Park Sports Ground 19. Croydon Road Rec 7 20. Crease Park 21. Cator Park 22. Mottingham Sports Ground / Foxes Fields 8 23. St Pauls Cray Hill Country Park 24. Pickhurst Rec 25. -

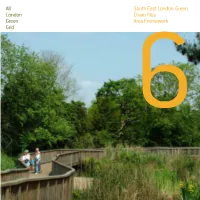

South East London Green Chain Plus Area Framework in 2007, Substantial Progress Has Been Made in the Development of the Open Space Network in the Area

All South East London Green London Chain Plus Green Area Framework Grid 6 Contents 1 Foreword and Introduction 2 All London Green Grid Vision and Methodology 3 ALGG Framework Plan 4 ALGG Area Frameworks 5 ALGG Governance 6 Area Strategy 8 Area Description 9 Strategic Context 10 Vision 12 Objectives 14 Opportunities 16 Project Identification 18 Project Update 20 Clusters 22 Projects Map 24 Rolling Projects List 28 Phase Two Early Delivery 30 Project Details 50 Forward Strategy 52 Gap Analysis 53 Recommendations 56 Appendices 56 Baseline Description 58 ALGG SPG Chapter 5 GGA06 Links 60 Group Membership Note: This area framework should be read in tandem with All London Green Grid SPG Chapter 5 for GGA06 which contains statements in respect of Area Description, Strategic Corridors, Links and Opportunities. The ALGG SPG document is guidance that is supplementary to London Plan policies. While it does not have the same formal development plan status as these policies, it has been formally adopted by the Mayor as supplementary guidance under his powers under the Greater London Authority Act 1999 (as amended). Adoption followed a period of public consultation, and a summary of the comments received and the responses of the Mayor to those comments is available on the Greater London Authority website. It will therefore be a material consideration in drawing up development plan documents and in taking planning decisions. The All London Green Grid SPG was developed in parallel with the area frameworks it can be found at the following link: http://www. london.gov.uk/publication/all-london-green-grid-spg . -

Elephant Park

Retail & Leisure 2 Embrace the spirit Retail at Elephant Park Embrace the spirit Retail at Elephant Park 3 Over 100,000 sq ft of floorspace Elephant Park: including affordable retail Opportunity-packed 50+ Zone 1 retail & shops, bars leisure space in & restaurants Elephant & Castle Four curated retail areas 4 Embrace the spirit Retail at Elephant Park Embrace the spirit Retail at Elephant Park 5 Be part of 2,700 a £2.3 billion new homes regeneration scheme at 97,000 sq m largest new park in Elephant Park Central London for 70 years Introducing Elephant Park, set to become the new heart of Elephant & Castle. This ambitious new development will transform and reconnect the area with its network of walkable streets and tree-lined squares, offering residents £30m transport investment and workers a place to meet, socialise and relax. Goodge Street Exmouth Market 6 Embrace the spirit Retail at Elephant Park Embrace the spirit Retail at Elephant Park 7 Barbican Liverpool Street Marylebone Moorgate Fitzrovia Oxford Circus Shopping Holborn Oxford Circus Farringdon Bond Street Tottenham Marble Arch Court Road Covent Garden THE STRAND Cheapside Soho Shopping Whitechapel City St Paul’s City of The Gherkin Thameslink Catherdral THE STRANDTemple Covent Garden London Leadenhall Market Tower Hill Leicester Shopping WATERLOO BRIDGE Monument Mayfair Square BLACKFRIARS BRIDGE SouthwarkPiccadilly One of London’s fastest-developing areas Circus Embankment LONDON BRIDGE Tower of St James’s Charing Tate Modern London Cross Southbank Centre London Green Park Borough Bridge Food Markets Market Flat Iron A3200 TOWER BRIDGE Elephant Park will offer an eclectic range of retail, leisure and F&B, all crafted to meet the demands Southwark Markets The Shard of the diverse customer profile. -

Planning Application Design & Access Statement Van-0387

PLANNING APPLICATION DESIGN & ACCESS STATEMENT VAN-0387 53 PERRY VALE, FOREST HILL, LONDON, SE23 2NE SEPTEMBER 2018 1.0 Contents VAN-0387 – 53 Perry Vale, Forest Hill, SE23 2NE, London Borough of Lewisham Design and Access Statement, July 2018 1.0 Contents 1 2.0 Introduction 2 3.0 Site analysis and Current Building 5 4.0 Description of the proposal 7 5.0 Use and Layout 10 6.0 Heritage Statement 12 7.0 Planning History and Policies 15 8.0 Architectural Character and Materials 15 9.0 Landscaping and Trees 19 10.0 Ecology 19 11.0 Extract, Ventilation and Services 20 12.0 Cycle Storage and Refuse 20 13.0 Sustainability and Renewable Energy Technology 21 14.0 Access & Mobility Statement 21 15.0 Transport, Traffic and parking Statement 22 16.0 Acoustics 22 17.0 Flood Risk 22 18.0 Statement of Community Engagement 23 19.0 Conclusion 24 1 2.0 Introduction VAN-0387 – 53 Perry Vale, Forest Hill, SE23 2NE, London Borough of Lewisham Design and Access Statement, July 2018 This application submission is prepared by db architects on behalf of Vanquish Iconic Developments for the site at 53 Perry Vale, Forest Hill, SE23 2NE. Vanquish are a family-run business and have been creating urban industrial interior designed developments for many years now across South East London. "We are a firm believer that property development should be creative, not made with basic materials to fit the standard criteria of a build. This is reflected in our interiors and exteriors of each finished development. -

Green Chain Walk Section 10

Transport for London.. Green Chain Walk. Section 10 of 11. Beckenham Place Park to Crystal Palace. Section start: Beckenham Place Park. Nearest stations Beckenham Hill . to start: Section finish: Crystal Palace. Nearest stations Crystal Palace to finish: Section distance: 3.9 miles (6.3 kilometres). Introduction. This section runs from Beckenham Place Park to Crystal Palace, a section steeped in heritage, with a Victorian Dinosaur Park at Crystal Palace Park and a rather unusual Edward VIII pillar box at Stumps Hill, made at Carron Ironworks. Directions. If starting at Beckenham Hill station, turn right from the station on to Beckenham Hill Road and cross this at the pedestrian lights. Enter Beckenham Place Park along the road by the gatehouse on your left and use the parallel footpath to Beckenham House Mansion, which is the start of section ten. From Beckenham House Mansion, take the footpath on the other side of the car park and head down to Southend Road. Upon reaching this, turn left and follow the road, crossing over to turn right into Stumps Hill Lane. At the Green Chain major signpost turn left along Worsley Bridge Road. At the T-junction turn right into Brackley Road towards St. Paul's church on the opposite side. Continue along Brackley Road to turn left into Copers Cope Road. Take the first right off Copers Cope Road to pass through the subway under New Beckenham railway station and into Lennard Road. From Lennard Road take the first left into King's Hall Road. Continue along King's Hall Road then turn right between numbers 173 and 175. -

354 Penge – Beckenham – Bromley

354 Penge–Beckenham–Bromley 354 Mondays to Fridays PengeCrookedBillet 0557 0617 0635 0653 0710 0727 0745 0804 0824 0845 0905 0925 1105 1124 1424 1442 AnerleyTownHall 0600 0620 0638 0656 0714 0731 0751 0810 0830 0851 0910 0929 1109 1128 1428 1447 BirkbeckStation 0603 0623 0641 0659 0717 0735 0755 0814 0834 0855 0914 0933 Then 1113 1132 Then 1432 1451 ClockHouseStation 0607 0627 0645 0704 0722 0740 0800 0819 0839 0900 0919 0938 every 1118 1137 every 1437 1456 BeckenhamWarMemorial(HighSt.) 0609 0629 0647 0706 0724 0743 0803 0823 0843 0903 0922 0941 20 1121 1140 20 1440 1459 BeckenhamHighSt.Marks&Spencer 0611 0631 0649 0709 0727 0747 0807 0827 0847 0907 0926 0945 mins. 1125 1144 mins. 1444 1503 FarnabyRoadRavensbourneAvenue 0616 0636 0655 0715 0733 0754 0814 0834 0854 0914 0933 0952 until 1132 1151 until 1451 1511 BromleyMarketSquare 0620 0640 0659 0719 0738 0759 0819 0839 0859 0919 0938 0957 1137 1156 1456 1516 BromleyNorthStation 0622 0642 0702 0722 0741 0802 0822 0842 0902 0922 0941 1000 1140 1159 1459 1519 PengeCrookedBillet 1501 1721 1741 1801 1821 1840 1858 1916 1936 1956 2016 2046 2116 2146 &&16 0016 AnerleyTownHall 1506 1726 1746 1806 1826 1844 1902 1920 1940 2000 2020 2049 2119 2149 &&19 0019 BirkbeckStation 1510 Then 1730 1750 1810 1830 1848 1906 1924 1944 2004 2023 2052 2122 2152 &&22 Then 0022 ClockHouseStation 1515 every 1735 1755 1815 1835 1853 1911 1929 1948 2008 2028 2057 2126 2156 &&26 every 0026 BeckenhamWarMemorial(HighSt.) 1519 20 1739 1759 1818 1837 1855 1913 1931 1950 2010 2030 2059 2128 2158 &&28 30 0028 BeckenhamHighSt.Marks&Spencer 1523 mins.