Beneath the Rubble, the Crystal Palace! the Surprising Persistence of a Temporary Mega Event

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of the East London Line

HISTORY OF THE EAST LONDON LINE – FROM BRUNEL’S THAMES TUNNEL TO THE LONDON OVERGROUND by Oliver Green A report of the LURS meeting at All Souls Club House on 11 October 2011 Oliver worked at the London Transport Museum for many years and was one of the team who set up the Covent Garden museum in 1980. He left in 1989 to continue his museum career in Colchester, Poole and Buckinghamshire before returning to LTM in 2001 to work on its recent major refurbishment and redisplay in the role of Head Curator. He retired from this post in 2009 but has been granted an honorary Research Fellowship and continues to assist the museum in various projects. He is currently working with LTM colleagues on a new history of the Underground which will be published by Penguin in October 2012 as part of LU’s 150th anniversary celebrations for the opening of the Met [Bishops Road to Farringdon Street 10 January 1863.] The early 1800s saw various schemes to tunnel under the River Thames, including one begun in 1807 by Richard Trevithick which was abandoned two years later when the workings were flooded. This was started at Rotherhithe, close to the site later chosen by Marc Isambard Brunel for his Thames Tunnel. In 1818, inspired by the boring technique of shipworms he had studied while working at Chatham Dockyard, Brunel patented a revolutionary method of digging through soft ground using a rectangular shield. His giant iron shield was divided into 12 independently moveable protective frames, each large enough for a miner to work in. -

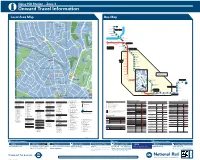

Local Area Map Bus Map

Gipsy Hill Station – Zone 3 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map Emmanuel Church 102 ST. GOTHARD ROAD 26 94 1 Dulwich Wood A 9 CARNAC STREET Sydenham Hill 25 LY Nursery School L A L L CHALFORD ROAD AV E N U E L 92 B HAMILTON ROAD 44 22 E O W Playground Y E UPPPPPPERE R L N I 53 30 T D N GREAT BROWNINGS T D KingswoodK d B E E T O N WAY S L R 13 A E L E A 16 I L Y E V 71 L B A L E P Estate E O E L O Y NELLO JAMES GARDENS Y L R N 84 Kingswood House A N A D R SYDEENE NNHAMAMM E 75 R V R 13 (Library and O S E R I 68 122 V A N G L Oxford Circus N3 Community Centre) E R 3 D U E E A K T S E B R O W N I N G L G I SSeeeleyeele Drivee 67 2 S E 116 21 H WOODSYRE 88 1 O 282 L 1 LITTLE BORNES 2 U L M ROUSE GARDENS Regent Street M O T O A U S N T L O S E E N 1 A C R E C Hamley’s Toy Store A R D G H H E S C 41 ST. BERNARDS A M 5 64 J L O N E L N Hillcrest WEST END 61 CLOSE 6 1 C 24 49 60 E C L I V E R O A D ST. -

Walks Programme: July to September 2021

LONDON STROLLERS WALKS PROGRAMME: JULY TO SEPTEMBER 2021 NOTES AND ANNOUNCEMENTS IMPORTANT NOTE REGARDING COVID-19: Following discussions with Ramblers’ Central Office, it has been confirmed that as organized ‘outdoor physical activity events’, Ramblers’ group walks are exempt from other restrictions on social gatherings. This means that group walks in London can continue to go ahead. Each walk is required to meet certain requirements, including maintenance of a register for Test and Trace purposes, and completion of risk assessments. There is no longer a formal upper limit on numbers for walks; however, since Walk Leaders are still expected to enforce social distancing, and given the difficulties of doing this with large numbers, we are continuing to use a compulsory booking system to limit numbers for the time being. Ramblers’ Central Office has published guidance for those wishing to join group walks. Please be sure to read this carefully before going on a walk. It is available on the main Ramblers’ website at www.ramblers.org.uk. The advice may be summarised as: - face masks must be carried and used, for travel to and from a walk on public transport, and in case of an unexpected incident; - appropriate social distancing must be maintained at all times, especially at stiles or gates; - you should consider bringing your own supply of hand sanitiser, and - don’t share food, drink or equipment with others. Some other important points are as follows: 1. BOOKING YOUR PLACE ON A WALK If you would like to join one of the walks listed below, please book a place by following the instructions given below. -

Mais House - Sydenham Hill GLA

Mais House - Sydenham Hill GLA 21.02.19 Front Cover Aerial View of Sydenham Hill Hawkins\Brown © | 06.12.18 | HB18049 | Pre-App Information Contents 1.0 Introduction 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Project Brief 2.0 Site & Context 2.1 Site Location & Connectivity 2.2 Site Topography 2.3 Land Use 2.4 Transport & Connections 2.5 Physical & Urban Context 2.6 The Existing Estate 2.7 Existing Building Heights 2.8 Existing Transport Connections & Movement 2.9 Landscaping & Townscape 2.10 Amenity & Green Space 2.11 Existing Tree Analysis 2.12 Existing Landscape Analysis 3.0 Heritage Appraisal 3.1 Kirkdale Conservation Area & Listed Buildings 3.2 Historic Maps 3.3 Compositional Development 3.4 Lammas Green 3.5 The Mansions 4.0 Masterplanning Principles 4.1 Overlooking Distances 4.2 Existing Trees 4.3 Development Area 4.4 Masterplan Diagrams 5.0 The Proposals 5.1 Opportunities & Constraints, Potential Development Area 5.2 Proposal Overview 5.3 Proposal Plans 5.4 Sydenham Hill Road/ Kirkdale Road Proposed Elevations 5.5 Proposal Key View 01 5.6 Proposal Key View 02 5.7 Development Key View 01 5.8 Development Key View 02 5.9 Parking and Access Appendices A Topographical Survey B Existing Tree Plan C Existing Tree Constraints Plan Hawkins\Brown © | 06.12.18 | HB18049 | Pre-App Information 3 Hawkins\Brown © | 06.12.18 | HB18049 | Pre-App Information 4 1.0 Introduction 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Project Brief Hawkins\Brown © | 06.12.18 | HB18049 | Pre-App Information 5 1.0 Introduction 1.1 Introduction Brief The City of London Corporation are looking to redevelop the Sydenham Hill Estate in the London Borough of Lewisham. -

Bromley May 2018

Traffic noise maps of public parks in Bromley May 2018 This document shows traffic noise maps for parks in the borough. The noise maps are taken from http://www.extrium.co.uk/noiseviewer.html. Occasionally, google earth or google map images are included to help the reader identify where the park is located. Similar documents are available for all London Boroughs. These were created as part of research into the impact of traffic noise in London’s parks. They should be read in conjunction with the main report and data analysis which are available at http://www.cprelondon.org.uk/resources/item/2390-noiseinparks. The key to the traffic noise maps is shown here to the right. Orange denotes noise of 55 decibels (dB). Louder noises are denoted by reds and blues with dark blue showing the loudest. Where the maps appear with no colour and are just grey, this means there is no traffic noise of 55dB or above. London Borough of Bromley 1 1.Betts Park 2.Crystal Palace Park 3.Elmstead Wood 2 4.Goddington Park 5.Harvington Sports Ground 6.Hayes Common 3 7.High Elms Country Park 8.Hoblingwell Wood 9.Scadbury Park 10.Jubilee Country Park 4 11.Kelsey Park 12.South Park 13.Norman Park 5 14.Southborough Recreation Ground 15.Swanley Park 16.Winsford Gardens 6 17. Spring Park 18. Langley Park Sports Ground 19. Croydon Road Rec 7 20. Crease Park 21. Cator Park 22. Mottingham Sports Ground / Foxes Fields 8 23. St Pauls Cray Hill Country Park 24. Pickhurst Rec 25. -

Brunel's Dream

Global Foresights | Global Trends and Hitachi’s Involvement Brunel’s Dream Kenji Kato Industrial Policy Division, Achieving Comfortable Mobility Government and External Relations Group, Hitachi, Ltd. The design of Paddington Station’s glass roof was infl u- Renowned Engineer Isambard enced by the Crystal Palace building erected as the venue for Kingdom Brunel London’s fi rst Great Exhibition held in 1851. Brunel was also involved in the planning for Crystal Palace, serving on the The resigned sigh that passed my lips on arriving at Heathrow building committee of the Great Exhibition, and acclaimed Airport was prompted by the long queues at immigration. the resulting structure of glass and iron. Being the gateway to London, a city known as a melting pot Rather than pursuing effi ciency in isolation, Brunel’s of races, the arrivals processing area was jammed with travel- approach to constructing the Great Western Railway was to ers from all corners of the world; from Europe of course, but make the railway lines as fl at as possible so that passengers also from the Middle East, Africa, Asia, and North and South could enjoy a pleasant journey while taking in Britain’s won- America. What is normally a one-hour wait can stretch to derful rural scenery. He employed a variety of techniques to two or more hours if you are unfortunate enough to catch a overcome the constraints of the terrain, constructing bridges, busy time of overlapping fl ight arrivals. While this only adds cuttings, and tunnels to achieve this purpose. to the weariness of a long journey, the prospect of comfort Rain, Steam and Speed – The Great Western Railway, a famous awaits you on the other side. -

South East London Green Chain Plus Area Framework in 2007, Substantial Progress Has Been Made in the Development of the Open Space Network in the Area

All South East London Green London Chain Plus Green Area Framework Grid 6 Contents 1 Foreword and Introduction 2 All London Green Grid Vision and Methodology 3 ALGG Framework Plan 4 ALGG Area Frameworks 5 ALGG Governance 6 Area Strategy 8 Area Description 9 Strategic Context 10 Vision 12 Objectives 14 Opportunities 16 Project Identification 18 Project Update 20 Clusters 22 Projects Map 24 Rolling Projects List 28 Phase Two Early Delivery 30 Project Details 50 Forward Strategy 52 Gap Analysis 53 Recommendations 56 Appendices 56 Baseline Description 58 ALGG SPG Chapter 5 GGA06 Links 60 Group Membership Note: This area framework should be read in tandem with All London Green Grid SPG Chapter 5 for GGA06 which contains statements in respect of Area Description, Strategic Corridors, Links and Opportunities. The ALGG SPG document is guidance that is supplementary to London Plan policies. While it does not have the same formal development plan status as these policies, it has been formally adopted by the Mayor as supplementary guidance under his powers under the Greater London Authority Act 1999 (as amended). Adoption followed a period of public consultation, and a summary of the comments received and the responses of the Mayor to those comments is available on the Greater London Authority website. It will therefore be a material consideration in drawing up development plan documents and in taking planning decisions. The All London Green Grid SPG was developed in parallel with the area frameworks it can be found at the following link: http://www. london.gov.uk/publication/all-london-green-grid-spg . -

Green Chain Walk Section 10

Transport for London.. Green Chain Walk. Section 10 of 11. Beckenham Place Park to Crystal Palace. Section start: Beckenham Place Park. Nearest stations Beckenham Hill . to start: Section finish: Crystal Palace. Nearest stations Crystal Palace to finish: Section distance: 3.9 miles (6.3 kilometres). Introduction. This section runs from Beckenham Place Park to Crystal Palace, a section steeped in heritage, with a Victorian Dinosaur Park at Crystal Palace Park and a rather unusual Edward VIII pillar box at Stumps Hill, made at Carron Ironworks. Directions. If starting at Beckenham Hill station, turn right from the station on to Beckenham Hill Road and cross this at the pedestrian lights. Enter Beckenham Place Park along the road by the gatehouse on your left and use the parallel footpath to Beckenham House Mansion, which is the start of section ten. From Beckenham House Mansion, take the footpath on the other side of the car park and head down to Southend Road. Upon reaching this, turn left and follow the road, crossing over to turn right into Stumps Hill Lane. At the Green Chain major signpost turn left along Worsley Bridge Road. At the T-junction turn right into Brackley Road towards St. Paul's church on the opposite side. Continue along Brackley Road to turn left into Copers Cope Road. Take the first right off Copers Cope Road to pass through the subway under New Beckenham railway station and into Lennard Road. From Lennard Road take the first left into King's Hall Road. Continue along King's Hall Road then turn right between numbers 173 and 175. -

The Crystal Palace

The Crystal Palace The Crystal Palace was a cast-iron and plate-glass structure originally The Crystal Palace built in Hyde Park, London, to house the Great Exhibition of 1851. More than 14,000 exhibitors from around the world gathered in its 990,000-square-foot (92,000 m2) exhibition space to display examples of technology developed in the Industrial Revolution. Designed by Joseph Paxton, the Great Exhibition building was 1,851 feet (564 m) long, with an interior height of 128 feet (39 m).[1] The invention of the cast plate glass method in 1848 made possible the production of large sheets of cheap but strong glass, and its use in the Crystal Palace created a structure with the greatest area of glass ever seen in a building and astonished visitors with its clear walls and ceilings that did not require interior lights. It has been suggested that the name of the building resulted from a The Crystal Palace at Sydenham (1854) piece penned by the playwright Douglas Jerrold, who in July 1850 General information wrote in the satirical magazine Punch about the forthcoming Great Status Destroyed Exhibition, referring to a "palace of very crystal".[2] Type Exhibition palace After the exhibition, it was decided to relocate the Palace to an area of Architectural style Victorian South London known as Penge Common. It was rebuilt at the top of Town or city London Penge Peak next to Sydenham Hill, an affluent suburb of large villas. It stood there from 1854 until its destruction by fire in 1936. The nearby Country United Kingdom residential area was renamed Crystal Palace after the famous landmark Coordinates 51.4226°N 0.0756°W including the park that surrounds the site, home of the Crystal Palace Destroyed 30 November 1936 National Sports Centre, which had previously been a football stadium Cost £2 million that hosted the FA Cup Final between 1895 and 1914. -

The Crystal Palace and Great Exhibition of 1851

Gale Primary Sources Start at the source. The Crystal Palace and Great Exhibition of 1851 Ed King British Library Various source media, British Library Newpapers EMPOWER™ RESEARCH The Crystal Palace evokes a response from almost exhibition of 1849 was visited by 100,000 people.2 As the everyone that you meet. Its fame is part of our culture. introduction to the catalogue of the 1846 exhibition The origin of the Crystal Palace lay in a decision made explained: in 1849 by Albert, the Prince Consort, together with a small group of friends and advisers, to hold an international exhibition in 1851 of the industry of all 'We are persuaded that if artistic manufactures are not appreciated, it is because they are not widely enough known. We believe that when nations. This exhibition came to have the title of: 'Great works of high merit, of British origin, are brought forward, they will Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations', be fully appreciated and thoroughly enjoyed. ... this exhibition when normally shortened to 'Great Exhibition'. 3 thrown ... open to all will tend to improve the public taste.' There had been exhibitions prior to the Great Exhibition. This declaration of intent has a prophetic ring about it, These had occurred in Britain and also in France and when we consider what eventually happened in 1851. Germany.1 The spirit of competition fostered by the trade of mass-produced goods between nations created, to some extent, a need to exhibit goods. This, The Crystal Palace in Hyde Park in turn, promoted the sale of goods. -

Buses from Old Kent Road

Buses from Old Kent Road 168 Newington Green 21 78 Belsize Park Hampstead Heath 453 Royal Free Hospital Shoreditch Marylebone Hoxton Curtain Road Chalk Farm 63 Baring Street Shoreditch High Street King’s Cross 0RRUÀHOGV Camden Town for St Pancras International Baker Street Eye Hospital Liverpool Street for Madame Tussauds Mornington Crescent Mount Pleasant Old Street CITY Euston Farringdon Aldgate Regent’s Park Eversholt Street Moorgate St Paul’s King Edward Finsbury Square Tower Gateway Russell Square Cathedral St Paul’s Street for Fenchurch Street , Tower Hill , Tower Millenium Pier 172 Bank Holborn and Tower of London Great Portland Street Ludgate Circus Route finder for City Thameslink Monument River Thames Blackfriars Oxford Circus Fleet Tower Bridge ROTHERHITHE Day buses including 24-hour routes Street City Hall Southwark Jamaica Road Jamaica Road Rotherhithe Bus route Towards Bus stops Piccadilly Circus Aldwych Street &UXFLÀ[/DQH Tanner Street Abbey Street Bermondsey Southwark Park Tunnel Entrance Rotherhithe for Covent Garden and London London Bridge Tower Bridge Road Jamaica Road Jamaica Road Jamaica Road Transport Museum Blackfriars Road for Guy’s Hospital and Druid Street Dockhead St James’s Road Drummond Road Salter Road 21 Lewisham Lower Road Canada Regent Street Southwark Street the London Dungeon Water for Blackfriars Surrey Quays Road Newington Green Tower Bridge Road Southwark Park Road Stamford Street Abbey Street Kirby Estate Trafalgar Square Borough BERMONDSEY Redriff Road Onega Gate 24 hour for Charing -

Times Are Changing at Sydenham Hill

This autumn, we’ll be running an amended weekday timetable shown below affecting Times are changing Off-Peak* metro services, but only on days when we expect the weather to be at its worst. at Sydenham Hill Check your journey up to 3 days in advance at southeasternrailway.co.uk/autumn Trains to London Mondays to Fridays There will be a minimum of 2 trains per hour Off-Peak, mainly at 18 and 48 minutes past the hour towards London. Sydenham Hill d 0518 0548 0618 0630 0650 0703 0710 0734 0740 0749 0803 0810 0817 0840 0847 0903 0910 0917 0933 0949 1003 1018 1048 1103 1118 1133 West Dulwich d 0520 0550 0620 0632 0652 0705 0712 — 0742 0752 0806 0812 0820 0842 0850 0905 0912 0920 0935 0951 1005 1020 1050 1105 1120 1135 Herne Hill a 0522 0552 0622 0634 0654 0707 0715 0737 0745 0754 0808 0815 0822 0845 0852 0907 0915 0922 0937 0953 1007 1022 1052 1107 1122 1137 Loughborough Jn d — — — — — — 0719 — 0749 — — 0819 — 0849 — — 0919 — — — — — — — — — Elephant & Castle d — — — — — — 0723 — 0753 — — 0823 — 0853 — — 0923 — — — — — — — — — London Blackfriars a — — — — — — 0729 — 0759 — — 0829 — 0859 — — 0929 — — — — — — — — — Brixton d 0526 0556 0626 0638 0658 0711 — 0741 — 0758 0812 — 0826 — 0856 0911 — 0926 0941 0957 1011 1026 1056 1111 1126 1141 London Victoria a 0535 0605 0635 0647 0707 0720 — 0750 — 0807 0821 — 0835 — 0905 0921 — 0935 0950 1004 1020 1033 1103 1118 1133 1148 Sydenham Hill d 1148 1218 1248 1518 1548 1603 1618 1648 1718 1733 1748 1803 1818 1833 1848 1918 1948 2018 2033 2048 2103 2118 2133 2148 West Dulwich d 1150 1220 1250 and at 1520