Distribution and Systematics of Notropis Wickliffi (Cypriniformes: Cyprinidae) in Illinois

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carmine Shiner (Notropis Percobromus) in Canada

COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Carmine Shiner Notropis percobromus in Canada THREATENED 2006 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION ENDANGERED WILDLIFE DES ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL IN CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC 2006. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the carmine shiner Notropis percobromus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 29 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Previous reports COSEWIC 2001. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the carmine shiner Notropis percobromus and rosyface shiner Notropis rubellus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. v + 17 pp. Houston, J. 1994. COSEWIC status report on the rosyface shiner Notropis rubellus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-17 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge D.B. Stewart for writing the update status report on the carmine shiner Notropis percobromus in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada, overseen and edited by Robert Campbell, Co-chair, COSEWIC Freshwater Fishes Species Specialist Subcommittee. In 1994 and again in 2001, COSEWIC assessed minnows belonging to the rosyface shiner species complex, including those in Manitoba, as rosyface shiner (Notropis rubellus). For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Évaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la tête carminée (Notropis percobromus) au Canada – Mise à jour. -

Notropis Girardi) and Peppered Chub (Macrhybopsis Tetranema)

Arkansas River Shiner and Peppered Chub SSA, October 2018 Species Status Assessment Report for the Arkansas River Shiner (Notropis girardi) and Peppered Chub (Macrhybopsis tetranema) Arkansas River shiner (bottom left) and peppered chub (top right - two fish) (Photo credit U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) Arkansas River Shiner and Peppered Chub SSA, October 2018 Version 1.0a October 2018 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 2 Albuquerque, NM This document was prepared by Angela Anders, Jennifer Smith-Castro, Peter Burck (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) – Southwest Regional Office) Robert Allen, Debra Bills, Omar Bocanegra, Sean Edwards, Valerie Morgan (USFWS –Arlington, Texas Field Office), Ken Collins, Patricia Echo-Hawk, Daniel Fenner, Jonathan Fisher, Laurence Levesque, Jonna Polk (USFWS – Oklahoma Field Office), Stephen Davenport (USFWS – New Mexico Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office), Mark Horner, Susan Millsap (USFWS – New Mexico Field Office), Jonathan JaKa (USFWS – Headquarters), Jason Luginbill, and Vernon Tabor (Kansas Field Office). Suggested reference: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2018. Species status assessment report for the Arkansas River shiner (Notropis girardi) and peppered chub (Macrhybopsis tetranema), version 1.0, with appendices. October 2018. Albuquerque, NM. 172 pp. Arkansas River Shiner and Peppered Chub SSA, October 2018 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ES.1 INTRODUCTION (CHAPTER 1) The Arkansas River shiner (Notropis girardi) and peppered chub (Macrhybopsis tetranema) are restricted primarily to the contiguous river segments of the South Canadian River basin spanning eastern New Mexico downstream to eastern Oklahoma (although the peppered chub is less widespread). Both species have experienced substantial declines in distribution and abundance due to habitat destruction and modification from stream dewatering or depletion from diversion of surface water and groundwater pumping, construction of impoundments, and water quality degradation. -

Indiana Species April 2007

Fishes of Indiana April 2007 The Wildlife Diversity Section (WDS) is responsible for the conservation and management of over 750 species of nongame and endangered wildlife. The list of Indiana's species was compiled by WDS biologists based on accepted taxonomic standards. The list will be periodically reviewed and updated. References used for scientific names are included at the bottom of this list. ORDER FAMILY GENUS SPECIES COMMON NAME STATUS* CLASS CEPHALASPIDOMORPHI Petromyzontiformes Petromyzontidae Ichthyomyzon bdellium Ohio lamprey lampreys Ichthyomyzon castaneus chestnut lamprey Ichthyomyzon fossor northern brook lamprey SE Ichthyomyzon unicuspis silver lamprey Lampetra aepyptera least brook lamprey Lampetra appendix American brook lamprey Petromyzon marinus sea lamprey X CLASS ACTINOPTERYGII Acipenseriformes Acipenseridae Acipenser fulvescens lake sturgeon SE sturgeons Scaphirhynchus platorynchus shovelnose sturgeon Polyodontidae Polyodon spathula paddlefish paddlefishes Lepisosteiformes Lepisosteidae Lepisosteus oculatus spotted gar gars Lepisosteus osseus longnose gar Lepisosteus platostomus shortnose gar Amiiformes Amiidae Amia calva bowfin bowfins Hiodonotiformes Hiodontidae Hiodon alosoides goldeye mooneyes Hiodon tergisus mooneye Anguilliformes Anguillidae Anguilla rostrata American eel freshwater eels Clupeiformes Clupeidae Alosa chrysochloris skipjack herring herrings Alosa pseudoharengus alewife X Dorosoma cepedianum gizzard shad Dorosoma petenense threadfin shad Cypriniformes Cyprinidae Campostoma anomalum central stoneroller -

RFP No. 212F for Endangered Species Research Projects for the Prairie Chub

1 RFP No. 212f for Endangered Species Research Projects for the Prairie Chub Final Report Contributing authors: David S. Ruppel, V. Alex Sotola, Ozlem Ablak Gurbuz, Noland H. Martin, and Timothy H. Bonner Addresses: Department of Biology, Texas State University, San Marcos, Texas 78666 (DSR, VAS, NHM, THB) Kirkkonaklar Anatolian High School, Turkish Ministry of Education, Ankara, Turkey (OAG) Principal investigators: Timothy H. Bonner and Noland H. Martin Email: [email protected], [email protected] Date: July 31, 2017 Style: American Fisheries Society Funding sources: Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts, Turkish Ministry of Education- Visiting Scholar Program (OAG) Summary Four hundred mesohabitats were sampled from 36 sites and 20 reaches within the upper Red River drainage from September 2015 through September 2016. Fishes (N = 36,211) taken from the mesohabitats represented 14 families and 49 species with the most abundant species consisting of Red Shiner Cyprinella lutrensis, Red River Shiner Notropis bairdi, Plains Minnow Hybognathus placitus, and Western Mosquitofish Gambusia affinis. Red River Pupfish Cyprinodon rubrofluviatilis (a species of greatest conservation need, SGCN) and Plains Killifish Fundulus zebrinus were more abundant within prairie streams (e.g., swift and shallow runs with sand and silt substrates) with high specific conductance. Red River Shiner (SGCN), Prairie Chub Macrhybopsis australis (SGCN), and Plains Minnow were more abundant within prairie 2 streams with lower specific conductance. The remaining 44 species of fishes were more abundant in non-prairie stream habitats with shallow to deep waters, which were more common in eastern tributaries of the upper Red River drainage and Red River mainstem. Prairie Chubs comprised 1.3% of the overall fish community and were most abundant in Pease River and Wichita River. -

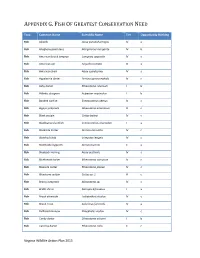

Fish of Greatest Conservation Need

APPENDIX G. FISH OF GREATEST CONSERVATION NEED Taxa Common Name Scientific Name Tier Opportunity Ranking Fish Alewife Alosa pseudoharengus IV a Fish Allegheny pearl dace Margariscus margarita IV b Fish American brook lamprey Lampetra appendix IV c Fish American eel Anguilla rostrata III a Fish American shad Alosa sapidissima IV a Fish Appalachia darter Percina gymnocephala IV c Fish Ashy darter Etheostoma cinereum I b Fish Atlantic sturgeon Acipenser oxyrinchus I b Fish Banded sunfish Enneacanthus obesus IV c Fish Bigeye jumprock Moxostoma ariommum III c Fish Black sculpin Cottus baileyi IV c Fish Blackbanded sunfish Enneacanthus chaetodon I a Fish Blackside darter Percina maculata IV c Fish Blotched chub Erimystax insignis IV c Fish Blotchside logperch Percina burtoni II a Fish Blueback Herring Alosa aestivalis IV a Fish Bluebreast darter Etheostoma camurum IV c Fish Blueside darter Etheostoma jessiae IV c Fish Bluestone sculpin Cottus sp. 1 III c Fish Brassy Jumprock Moxostoma sp. IV c Fish Bridle shiner Notropis bifrenatus I a Fish Brook silverside Labidesthes sicculus IV c Fish Brook Trout Salvelinus fontinalis IV a Fish Bullhead minnow Pimephales vigilax IV c Fish Candy darter Etheostoma osburni I b Fish Carolina darter Etheostoma collis II c Virginia Wildlife Action Plan 2015 APPENDIX G. FISH OF GREATEST CONSERVATION NEED Fish Carolina fantail darter Etheostoma brevispinum IV c Fish Channel darter Percina copelandi III c Fish Clinch dace Chrosomus sp. cf. saylori I a Fish Clinch sculpin Cottus sp. 4 III c Fish Dusky darter Percina sciera IV c Fish Duskytail darter Etheostoma percnurum I a Fish Emerald shiner Notropis atherinoides IV c Fish Fatlips minnow Phenacobius crassilabrum II c Fish Freshwater drum Aplodinotus grunniens III c Fish Golden Darter Etheostoma denoncourti II b Fish Greenfin darter Etheostoma chlorobranchium I b Fish Highback chub Hybopsis hypsinotus IV c Fish Highfin Shiner Notropis altipinnis IV c Fish Holston sculpin Cottus sp. -

Information on the NCWRC's Scientific Council of Fishes Rare

A Summary of the 2010 Reevaluation of Status Listings for Jeopardized Freshwater Fishes in North Carolina Submitted by Bryn H. Tracy North Carolina Division of Water Resources North Carolina Department of Environment and Natural Resources Raleigh, NC On behalf of the NCWRC’s Scientific Council of Fishes November 01, 2014 Bigeye Jumprock, Scartomyzon (Moxostoma) ariommum, State Threatened Photograph by Noel Burkhead and Robert Jenkins, courtesy of the Virginia Division of Game and Inland Fisheries and the Southeastern Fishes Council (http://www.sefishescouncil.org/). Table of Contents Page Introduction......................................................................................................................................... 3 2010 Reevaluation of Status Listings for Jeopardized Freshwater Fishes In North Carolina ........... 4 Summaries from the 2010 Reevaluation of Status Listings for Jeopardized Freshwater Fishes in North Carolina .......................................................................................................................... 12 Recent Activities of NCWRC’s Scientific Council of Fishes .................................................. 13 North Carolina’s Imperiled Fish Fauna, Part I, Ohio Lamprey .............................................. 14 North Carolina’s Imperiled Fish Fauna, Part II, “Atlantic” Highfin Carpsucker ...................... 17 North Carolina’s Imperiled Fish Fauna, Part III, Tennessee Darter ...................................... 20 North Carolina’s Imperiled Fish Fauna, Part -

Endangered Species

FEATURE: ENDANGERED SPECIES Conservation Status of Imperiled North American Freshwater and Diadromous Fishes ABSTRACT: This is the third compilation of imperiled (i.e., endangered, threatened, vulnerable) plus extinct freshwater and diadromous fishes of North America prepared by the American Fisheries Society’s Endangered Species Committee. Since the last revision in 1989, imperilment of inland fishes has increased substantially. This list includes 700 extant taxa representing 133 genera and 36 families, a 92% increase over the 364 listed in 1989. The increase reflects the addition of distinct populations, previously non-imperiled fishes, and recently described or discovered taxa. Approximately 39% of described fish species of the continent are imperiled. There are 230 vulnerable, 190 threatened, and 280 endangered extant taxa, and 61 taxa presumed extinct or extirpated from nature. Of those that were imperiled in 1989, most (89%) are the same or worse in conservation status; only 6% have improved in status, and 5% were delisted for various reasons. Habitat degradation and nonindigenous species are the main threats to at-risk fishes, many of which are restricted to small ranges. Documenting the diversity and status of rare fishes is a critical step in identifying and implementing appropriate actions necessary for their protection and management. Howard L. Jelks, Frank McCormick, Stephen J. Walsh, Joseph S. Nelson, Noel M. Burkhead, Steven P. Platania, Salvador Contreras-Balderas, Brady A. Porter, Edmundo Díaz-Pardo, Claude B. Renaud, Dean A. Hendrickson, Juan Jacobo Schmitter-Soto, John Lyons, Eric B. Taylor, and Nicholas E. Mandrak, Melvin L. Warren, Jr. Jelks, Walsh, and Burkhead are research McCormick is a biologist with the biologists with the U.S. -

Fishes of South Dakota

MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATIONS MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN, NO. 119 Fishes of South Dakota REEVE M. BAILEY AND MARVIN 0. ALLUM South Dakota State College ANN ARBOR MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN JUNE 5, 1962 MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATIONS MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY 01; MICHIGAN The publications of the Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan, consist of two series-the Occasional Papers and the Miscellaneous Publications. Both series were founded by Dr. Bryant Walker, Mr. Bradshaw H. Swales, and Dr. W. W. Newcomb. The Occasional Papers, publication of which was begun in 1913, serve as a medium for original studies based principally upon the collections in the Museum. They are issued separately. When a sufficient number of pages has been printed to make a volume, a title page, table of contents, and an index are supplied to libraries and indi- viduals on the mailing list for the series. The Miscellaneous Publications, which include papers on field and museum tech- niques, monographic studies, and other contributions not within the scope of the Occasional Papers, are published separately. It is not intended that they be grouped into volumes. Each number has a title page and, when necessary, a table of contents. A conlplete list of publications on Birds, Fishes, Insects, Mammals, Mollusks, and Reptiles and Amphibians is available. Address inquiries to the Director, Museum of Zoology, Ann Arbor, Michigan No. 13. Studies of the fishes of the order Cyprinodontes. By CARL L. HUBBS. (1924) 23 pp., 4 pls. ............................................. No. 15. A check-list of the fishes of the Great Lakes and tributary waters, with nomenclatorial notes and analytical keys. -

Aquatic Fish Report

Aquatic Fish Report Acipenser fulvescens Lake St urgeon Class: Actinopterygii Order: Acipenseriformes Family: Acipenseridae Priority Score: 27 out of 100 Population Trend: Unknown Gobal Rank: G3G4 — Vulnerable (uncertain rank) State Rank: S2 — Imperiled in Arkansas Distribution Occurrence Records Ecoregions where the species occurs: Ozark Highlands Boston Mountains Ouachita Mountains Arkansas Valley South Central Plains Mississippi Alluvial Plain Mississippi Valley Loess Plains Acipenser fulvescens Lake Sturgeon 362 Aquatic Fish Report Ecobasins Mississippi River Alluvial Plain - Arkansas River Mississippi River Alluvial Plain - St. Francis River Mississippi River Alluvial Plain - White River Mississippi River Alluvial Plain (Lake Chicot) - Mississippi River Habitats Weight Natural Littoral: - Large Suitable Natural Pool: - Medium - Large Optimal Natural Shoal: - Medium - Large Obligate Problems Faced Threat: Biological alteration Source: Commercial harvest Threat: Biological alteration Source: Exotic species Threat: Biological alteration Source: Incidental take Threat: Habitat destruction Source: Channel alteration Threat: Hydrological alteration Source: Dam Data Gaps/Research Needs Continue to track incidental catches. Conservation Actions Importance Category Restore fish passage in dammed rivers. High Habitat Restoration/Improvement Restrict commercial harvest (Mississippi River High Population Management closed to harvest). Monitoring Strategies Monitor population distribution and abundance in large river faunal surveys in cooperation -

Geological Survey of Alabama Calibration of The

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF ALABAMA Berry H. (Nick) Tew, Jr. State Geologist WATER INVESTIGATIONS PROGRAM CALIBRATION OF THE INDEX OF BIOTIC INTEGRITY FOR THE SOUTHERN PLAINS ICHTHYOREGION IN ALABAMA OPEN-FILE REPORT 0908 by Patrick E. O'Neil and Thomas E. Shepard Prepared in cooperation with the Alabama Department of Environmental Management and the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Tuscaloosa, Alabama 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................ 1 Introduction.......................................................... 1 Acknowledgments .................................................... 6 Objectives........................................................... 7 Study area .......................................................... 7 Southern Plains ichthyoregion ...................................... 7 Methods ............................................................ 8 IBI sample collection ............................................. 8 Habitat measures............................................... 10 Habitat metrics ........................................... 12 The human disturbance gradient ................................... 15 IBI metrics and scoring criteria..................................... 19 Designation of guilds....................................... 20 Results and discussion................................................ 22 Sampling sites and collection results . 22 Selection and scoring of Southern Plains IBI metrics . 41 1. Number of native species ................................ -

Kansas Stream Fishes

A POCKET GUIDE TO Kansas Stream Fishes ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ By Jessica Mounts Illustrations © Joseph Tomelleri Sponsored by Chickadee Checkoff, Westar Energy Green Team, Kansas Department of Wildlife, Parks and Tourism, Kansas Alliance for Wetlands & Streams, and Kansas Chapter of the American Fisheries Society Published by the Friends of the Great Plains Nature Center Table of Contents • Introduction • 2 • Fish Anatomy • 3 • Species Accounts: Sturgeons (Family Acipenseridae) • 4 ■ Shovelnose Sturgeon • 5 ■ Pallid Sturgeon • 6 Minnows (Family Cyprinidae) • 7 ■ Southern Redbelly Dace • 8 ■ Western Blacknose Dace • 9 ©Ryan Waters ■ Bluntface Shiner • 10 ■ Red Shiner • 10 ■ Spotfin Shiner • 11 ■ Central Stoneroller • 12 ■ Creek Chub • 12 ■ Peppered Chub / Shoal Chub • 13 Plains Minnow ■ Silver Chub • 14 ■ Hornyhead Chub / Redspot Chub • 15 ■ Gravel Chub • 16 ■ Brassy Minnow • 17 ■ Plains Minnow / Western Silvery Minnow • 18 ■ Cardinal Shiner • 19 ■ Common Shiner • 20 ■ Bigmouth Shiner • 21 ■ • 21 Redfin Shiner Cover Photo: Photo by Ryan ■ Carmine Shiner • 22 Waters. KDWPT Stream ■ Golden Shiner • 22 Survey and Assessment ■ Program collected these Topeka Shiner • 23 male Orangespotted Sunfish ■ Bluntnose Minnow • 24 from Buckner Creek in Hodgeman County, Kansas. ■ Bigeye Shiner • 25 The fish were catalogued ■ Emerald Shiner • 26 and returned to the stream ■ Sand Shiner • 26 after the photograph. ■ Bullhead Minnow • 27 ■ Fathead Minnow • 27 ■ Slim Minnow • 28 ■ Suckermouth Minnow • 28 Suckers (Family Catostomidae) • 29 ■ River Carpsucker • -

Summary Report of Freshwater Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S

Summary Report of Freshwater Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 4—An Update April 2013 Prepared by: Pam L. Fuller, Amy J. Benson, and Matthew J. Cannister U.S. Geological Survey Southeast Ecological Science Center Gainesville, Florida Prepared for: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia Cover Photos: Silver Carp, Hypophthalmichthys molitrix – Auburn University Giant Applesnail, Pomacea maculata – David Knott Straightedge Crayfish, Procambarus hayi – U.S. Forest Service i Table of Contents Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................................... ii List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................ v List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................ vi INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 1 Overview of Region 4 Introductions Since 2000 ....................................................................................... 1 Format of Species Accounts ...................................................................................................................... 2 Explanation of Maps ................................................................................................................................