Barbara Kasten: out of the Box”, Ocula, 7 August, 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

October 2011 - January 2012

Art Exhibition October 2011 - January 2012 Barbara Kasten Barbara Kasten, a Chicago born artist, is best known for her photographs of well known architectural sites. She experiments with different photographic processes such as color, light and focus, while conveying meaning through the elements involved. Her use of architecture as an inspiration is prevalent throughout her art, and as seen here, she infuses pops of color to highlight vivid angles and sharp lines. She explores the relationship between light in a setting of large-scale assemblages, which ultimately makes light and shadows the subject. With influences from The Bauhaus and Constructivism, Kasten explores modes of reorganizing the visual environment while using geometric shapes and lighting to create an abstract interpretation. Barbara Kasten received her BFA in painting and sculpture from the University of Arizona in Tucson. She went on to receive her MFA from the California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland, CA. Kasten’s work can be seen in many prestigious museums throughout the U.S., Europe and Japan, including The Art Institute of Chicago, The Museum of Contemporary Photography and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. For more information about Barbara Kasten and her work, please contact Tony Wight Gallery at 312/492-7261 or visit www.tonywightgallery.com Bernard Williams Bernard Williams was born in Chicago and has worked in the mediums of painting, sculpture, metalwork, murals and installations. His interest in American and world history are evident as he pulls from the “melting pot” cultures that make up this country. Inspired by signs and symbols, Williams often arranges them in ways to depict the complexities of human and historical development. -

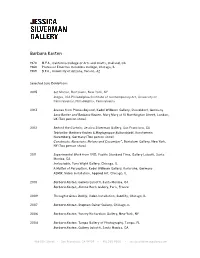

2015 Barbara KASTEN Resume

BARBARA KASTEN CURRICULUM VITAE EDUCATION 1970 M.F.A., California College of Arts and Crafts, Oakland, California 1959 B.F.A., University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona GUEST LECTURES 2015 “Kasten in Context: New Peers: Barbara Kasten in conversation with David Hartt, Takeshi Murata, and Sara VanDerBeek”, Insitiute of Contemporary Art, Philadephia, PA 2013 Panel: “Color Rush”, Aperture, AIPAD Conference, New York 2012 Expo Chicago, Panel “Eclectic Coherence,” Chicago, Illinois Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts, Washington University in St. Louis,MO 2010 Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona, Tucson 2009 Los Angeles County Museum of Art, “Artists Speak” series 2008 Columbia College Faculty Retreat, Distinguished Artist Presentation 2007 Columbia College Faculty Retreat, Distinguished Artist Presentation The New School, NY,representing Columbia College Photography Department 2004 Tampa Gallery of Photography, Tampa, Florida 2002 Art Museum, University of Memphis, Tennessee 1999 Columbia College Faculty Retreat, Panel “New Direction in Photography” Seminar Guest, Honors Program at Daley College, Chicago, Illinois “Chicago Photo” lecture series, The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois 1998 “Photography CHICAGO 1998”, Chicago, Illinois SPE National Convention, Panel “Going Commercial: Fine Art Photographers Explore Todayʼs Marketplace”, Tucson, Arizona 1997 Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 1996 Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York Ithaca College, Lecture and Workshop, Ithaca, New York 1994 VISCOMM 94, Javits Convention Center, New York, New York 1 MacWorld Exposition, Boston, Massachusetts 1993 Art and Photography Department, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York School of the Visual Arts, New York, New York 1992 Rochester Institute of Technology, Rochester, New York Society for Photographic Education, National Convention, Washington, D.C. -

For Immediate Release Barbara Kasten

For Immediate Release Barbara Kasten: Stages October 1–January 9, 2016 Chicago, August 5, 2015—The Graham Foundation, in partnership with the 2015 Chicago Architecture Biennial, is pleased to present Barbara Kasten: Stages, the first major survey of the work of Chicago-based artist Barbara Kasten. Widely known for her photographs, since the 1970s Kasten has developed an expansive practice through the lens of painting, textile, sculpture, theater, architecture, and installation. Organized in conversation with the artist and with full access to her extensive archive, the exhibition offers fresh vantages onto Kasten’s five-decade career as an innovative multidisciplinary artist engaged with abstraction, light, and architectonic space. Barbara Kasten: Stages situates the artist’s work within current conversations in art and architecture and traces its roots to the unique and provocative intersection of Bauhaus- influenced pedagogy in America, the California Light and Space movement, and the ethos and aesthetics of postmodernism. Kasten’s interest in the interplay between three- dimensional and two-dimensional forms, her concern with staging and the role of the prop, her cross-disciplinary process, and the way she has developed new approaches to abstraction and materiality are all intensely relevant to contemporary architecture’s critical engagement with visual arts practices as well as to a new generation of artists who have drawn inspiration from Kasten’s evolving aesthetic and process. Loosely chronological, the exhibition focuses on selections from major bodies of work spanning the 1970s to the present. It brings together and contextualizes for the first time Kasten’s earliest fiber sculptures, mixed media works, cyanotype prints, forays into set design, archival documents, and video documentation, along with Kasten’s best known photographic series—her studio constructions and architectural interventions. -

Barbara Kasten

Kadel Willborn Birkenstr. 3 D – 40233 Düsseldorf [email protected] www.kadel-willborn.de Barbara Kasten born 1936, lives and works in Chicago, US Education 1970 M.F.A., California College of Arts and Crafts, Oakland, California, US 1959 B.F.A., University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona, US Museum Collections Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas, US Ackland Art Museum, Chapel Hill, NC, US Art Gallery New South Wales, Sydney, AU Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, US Art Tower Mito Contemporary Art Gallery, Mito, Japan, US Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, Maryland, US Birmingham Museum of Art, Birmingham, Alabama, US California Museum of Photography, University of California Riverside, Riverside, US Contemporary Art Centre, Vilnius, LT Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona, US Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, FR Centro Cultural Arte Contemporaneo, Mexico City, US Fine Arts Museum of New Mexico, Santa Fe, New Mexico, US Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts, US Generali Foundation, Vienna, AT Hammer Museum, Uiversity of California at Los Angeles, Los Angeles, US Helen Forsman Spencer Museum of Art, Lawrence, Kansas, US High Museum of Art, Atlanta, Georgia, US International Center of Photography, New York, US International Museum of Photography at George Eastman House, Rochester, New York, US J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, US Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, Wolfsburg, DE Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California, US Madison Art Center, Madison, Wisconsin, US Museum der Moderne, Salzburg, AT Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York, US Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, Illinois, US Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, California, US Museum of Contemporary Photography, Columbia College, Chicago, Illinois, US Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas, US Museum of Fine Arts, Museum of New Mexico, Santa Fe, New Mexico, US Museum of Modern Art, Lodz, PL Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York, US Museum of Photographic Arts, San Diego, California, US 1 Kadel Willborn Birkenstr. -

Words Without Pictures

WORDS WITHOUT PICTURES NOVEMBER 2007– FEBRUARY 2009 Los Angeles County Museum of Art CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Charlotte Cotton, Alex Klein 1 NOVEMBER 2007 / ESSAY Qualifying Photography as Art, or, Is Photography All It Can Be? Christopher Bedford 4 NOVEMBER 2007 / DISCUSSION FORUM Charlotte Cotton, Arthur Ou, Phillip Prodger, Alex Klein, Nicholas Grider, Ken Abbott, Colin Westerbeck 12 NOVEMBER 2007 / PANEL DISCUSSION Is Photography Really Art? Arthur Ou, Michael Queenland, Mark Wyse 27 JANUARY 2008 / ESSAY Online Photographic Thinking Jason Evans 40 JANUARY 2008 / DISCUSSION FORUM Amir Zaki, Nicholas Grider, David Campany, David Weiner, Lester Pleasant, Penelope Umbrico 48 FEBRUARY 2008 / ESSAY foRm Kevin Moore 62 FEBRUARY 2008 / DISCUSSION FORUM Carter Mull, Charlotte Cotton, Alex Klein 73 MARCH 2008 / ESSAY Too Drunk to Fuck (On the Anxiety of Photography) Mark Wyse 84 MARCH 2008 / DISCUSSION FORUM Bennett Simpson, Charlie White, Ken Abbott 95 MARCH 2008 / PANEL DISCUSSION Too Early Too Late Miranda Lichtenstein, Carter Mull, Amir Zaki 103 APRIL 2008 / ESSAY Remembering and Forgetting Conceptual Art Alex Klein 120 APRIL 2008 / DISCUSSION FORUM Shannon Ebner, Phil Chang 131 APRIL 2008 / PANEL DISCUSSION Remembering and Forgetting Conceptual Art Sarah Charlesworth, John Divola, Shannon Ebner 138 MAY 2008 / ESSAY Who Cares About Books? Darius Himes 156 MAY 2008 / DISCUSSION FORUM Jason Fulford, Siri Kaur, Chris Balaschak 168 CONTENTS JUNE 2008 / ESSAY Minor Threat Charlie White 178 JUNE 2008 / DISCUSSION FORUM William E. Jones, Catherine -

Christian Marclay

US $25 The Global Journal of Prints and Ideas November – December 2016 Volume 6, Number 4 Panoramic Wallpaper in New England • Christian Marclay • Fantastic Architecture • Ania Jaworska • Barbara Kasten Degas Monotypes at MoMA • American Prints at the National Gallery • Matisse at the Morgan • Prix de Print • News PHILIP TAAFFE The Philip Taaffe E/AB Fair Benefit Prints are available at eabfair.org Philip Taaffe, Fossil Leaves, screenprint, 25x38” variable edition of 30 Philip Taaffe, St. Steven’s Lizards, screenprint, 25x34.5” variable edition of 30 Thanks to all the exhibitors and guests for a great fair! November – December 2016 In This Issue Volume 6, Number 4 Editor-in-Chief Susan Tallman 2 Susan Tallman On the Wall Associate Publisher Catherine Bindman 3 Julie Bernatz A French Panoramic Wallpaper in the Home of a New England Lawyer Managing Editor James Siena and Katia Santibañez 8 Isabella Kendrick Zuber in Otis Associate Editor Susan Tallman 10 Julie Warchol To The Last Syllable of Recorded Time: Christian Marclay Manuscript Editor Prudence Crowther Prix de Print, No. 20 16 Colin Lyons Editor-at-Large Time Machine for Catherine Bindman Abandoned Futures Juried by Chang Yuchen Design Director Skip Langer Exhibition Reviews Julie Warchol 18 Webmaster Ania Jaworska at MCA Chicago Dana Johnson Vincent Katz 21 Matisse Bound and Unbound Joseph Goldyne 25 New Light on Degas’ Dark Dramas Vincent Katz 29 Degas at MoMA Ivy Cooper 33 Prints in the Gateway City Lauren R. Fulton 35 On Paper, on Chairs: Barbara Kasten Book Reviews Paige K. Johnston 38 Higgins’ and Vostell’s Fantastic Architecture Catherine Bindman 40 (Printed) Art in America News of the Print World 43 On the Cover: Christian Marclay, detail of Actions: Splish, Plop, Plash, Plash (No. -

Barbara Kasten

Barbara Kasten 1970 M.F.A., California College of Arts and Crafts, Oakland, CA 1960 Professor Emeritus Columbia College, Chicago, IL 1959 B.F.A., University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ Selected Solo Exhibitions 2015 Set Motion, Bortolami, New York, NY Stages, ICA Philadelphia (Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 2013 Scenes from Places Beyond, Kadel Willborn Gallery, Dusseldorf, Germany Sara Barker and Barbara Kasten, Mary Mary at 10 Northington Street, London, UK (Two person show) 2012 Behind the Curtain, Jessica Silverman Gallery, San Francisco, CA Tektonika: Barbara Kasten & Magicgruppe Kulturobjekt, Kunstverein Nuremberg, Germany (Two person show) Constructs, Abrasions, Melons and Cucumber”, Bortolami Gallery, New York, NY (Two person show) 2011 Experimental Work from 1970, Pacific Standard Time, Gallery Luisotti, Santa Monica, CA Ineluctable, Tony Wight Gallery, Chicago, IL A Matter of Perception, Kadel Willborn Gallery, Karlsruhe, Germany REMIX, Video Installation, Applied Art, Chicago, IL 2010 Barbara Kasten, Gallery Luisotti, Santa Monica, CA Barbara Kasten, Almine Rech Gallery, Paris, France 2009 Through a Glass Darkly, Video Installation, SubCity, Chicago, IL 2007 Barbara Kasten, Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago, IL 2006 Barbara Kasten, Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York, NY 2004 Barbara Kasten, Tampa Gallery of Photography, Tampa, FL Barbara Kasten, Gallery Luisotti, Santa Monica, CA 488 Ellis Street San Francisco, CA 94109 415.255.9508 jessicasilvermangallery.com 2002 Art Museum, -

1 BARBARA KASTEN 312 371 9629 E-Mail: [email protected] CURRICULUM VITAE

BARBARA KASTEN 312 371 9629 E-mail: [email protected] www.barbarakasten.net CURRICULUM VITAE EDUCATION 1970 M.F.A., California College of Arts and Crafts, Oakland, California 1959 B.F.A., University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona AWARDS AND RESIDENCIES 2009 Faculty Development Grant, Columbia College Chicago 2006-8 Distinguished Artist, Columbia College Chicago 2005 Faculty Development Grant, Columbia College Chicago 1998 Graduate International Faculty Development Grant, Columbia College Chicago 1996 Artist in Residence, EKLISIA, Gumusluk, Turkey 1995 Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, Cornell Council for the Arts, Visiting Artist Residency, (March) USIA Arts America Cultural Specialist, (in Lithuania, Estonia, Latvia) Artist in Residence, EKLISIA, Gumusluk, Turkey 1991 Apple Digital Photography Grant Artist in Residence, Musee de Pont Aven, Pont Aven, France 1985 Capp Street Project Residency, San Francisco, California 1982 John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship Polaroid Collection Program (1982 - present) 1981 National Endowment of the Arts Grant; Project Director, Videotape Documentary, "High Heels and Ground Glass" Coast Community College District 1977 National Endowment of the Arts, Photography Fellowship 1971 Fulbright Hays Fellowship, Poland SOLO EXHIBITIONS 1 2010 ‘abstracting…light’, Almine Rech Gallery ,Paris, France ……. ……. ‘Shadow=Light’, Gallery Luisotti ,Santa Monica, CA 2009 ‘Through a Glass Darkly”, Video Installation, SubCity, Fine Arts Building, Chicago, IL 2007 Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago 2006 Yancey Richardson Gallery. -

Featured Releases 2 Limited Editions 102 Journals 109

Lorenzo Vitturi, from Money Must Be Made, published by SPBH Editions. See page 125. Featured Releases 2 Limited Editions 102 Journals 109 CATALOG EDITOR Thomas Evans Fall Highlights 110 DESIGNER Photography 112 Martha Ormiston Art 134 IMAGE PRODUCTION Hayden Anderson Architecture 166 COPY WRITING Design 176 Janine DeFeo, Thomas Evans, Megan Ashley DiNoia PRINTING Sonic Media Solutions, Inc. Specialty Books 180 Art 182 FRONT COVER IMAGE Group Exhibitions 196 Fritz Lang, Woman in the Moon (film still), 1929. From The Moon, Photography 200 published by Louisiana Museum of Modern Art. See Page 5. BACK COVER IMAGE From Voyagers, published by The Ice Plant. See page 26. Backlist Highlights 206 Index 215 Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future Edited with text by Tracey Bashkoff. Text by Tessel M. Bauduin, Daniel Birnbaum, Briony Fer, Vivien Greene, David Max Horowitz, Andrea Kollnitz, Helen Molesworth, Julia Voss. When Swedish artist Hilma af Klint died in 1944 at the age of 81, she left behind more than 1,000 paintings and works on paper that she had kept largely private during her lifetime. Believing the world was not yet ready for her art, she stipulated that it should remain unseen for another 20 years. But only in recent decades has the public had a chance to reckon with af Klint’s radically abstract painting practice—one which predates the work of Vasily Kandinsky and other artists widely considered trailblazers of modernist abstraction. Her boldly colorful works, many of them large-scale, reflect an ambitious, spiritually informed attempt to chart an invisible, totalizing world order through a synthesis of natural and geometric forms, textual elements and esoteric symbolism. -

The D.A.P. Catalog Fall 2020

THE D.A.P. CATALOG FALL 2020 Featured Releases 2 Limited Editions 78 Journals 79 CATALOG EDITOR Previously Announced Exhibition Catalogs 80 Thomas Evans DESIGNER Martha Ormiston Fall Highlights 82 COPY WRITING Arthur Cañedo, Megan Ashley DiNoia, Thomas Evans, Emilia Copeland Titus Photography 84 Art 108 ABOVE: Architecture & Design 144 B. Wurtz, various pan paintings. From B. Wurtz: Pan Paintings, published by Hunters Point Press. See page 127. Specialty Books 162 FRONT COVER: John Baldessari, Palm Tree/Seascape, 2010. From John Baldessari, published by Walther König, Art 164 Köln. See page 61. Photography 190 BACK COVER: Feliciano Centurión, Estoy vivo, 1994. From Feliciano Centurión, published by Americas Society. Backlist Highlights 197 See page 127. Index 205 Plus sign indicates that a title is listed on Edelweiss NEED HIGHER RES Gerhard Richter: Landscape The world’s most famous painter focuses on the depiction of natural environments, from sunsets to seascapes to suburban streets Gerhard Richter’s paintings combine photorealism and abstraction in a manner that is completely unique to the German artist. A master of texture, Richter has experimented with different techniques of paint application throughout his career. His hallmark is the illusion of motion blur in his paintings, which are referenced from photographs he himself has taken, obscuring his subjects with gentle brushstrokes or the scrape of a squeegee, softening the edges of his figures to appear as though they had been captured by an unfocused lens. This publication concentrates on the theme of landscape in Richter’s work, a genre to which he has remained faithful for over 60 years, capturing environments from seascapes to countryside. -

Craftfolkartinsf00annerich.Pdf

University of California Berkeley Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California California Craft Artists Oral History Series Margery Anneberg ANNEBERG GALLERY, 1966-1981, AND CRAFT AND FOLK ART IN THE SAN FRANCISCO BAY AREA With Introductions by Jack Lenor Larsen and June Schwarcz Interviews Conducted by Suzanne B. Riess in 1995 Copyright C 1998 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the Nation. Oral history is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well- informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ************************************ All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Margery Anneberg dated March 20, 1995. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. -

Barbara Kasten

Barbara Kasten 1970 M.F.A., California College of Arts and Crafts, Oakland, CA 1960 Professor Emeritus Columbia College, Chicago, IL 1959 B.F.A., University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ Solo Exhibitions 2013 Scenes from Places Beyond, Kadel Willborn Gallery, Dusseldorf, Germany Sara Barker and Barbara Kasten, Laura Bartlett Gallery, London, UK (Two person show) 2012 Behind the Curtain, Jessica Silverman Gallery, San Francisco, CA Tektonika: Barbara Kasten & Magicgruppe Kulturobjekt, Kunstverein Nuremberg, Germany (Two person show) Constructs, Abrasions, Melons and Cucumber”, Bortolami Gallery, New York, NY (Two person show) 2011 Experimental Work from 1970, Pacific Standard Time, Gallery Luisotti, Santa Monica, CA Ineluctable, Tony Wight Gallery, Chicago, IL A Matter of Perception, Kadel Willborn Gallery, Karlsruhe, Germany REMIX, Video Installation, Applied Art, Chicago, IL 2010 Barbara Kasten, Gallery Luisotti, Santa Monica, CA Barbara Kasten, Almine Rech Gallery, Paris, France 2009 Through a Glass Darkly, Video Installation, SubCity, Chicago, IL 2007 Barbara Kasten, Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago, IL 2006 Barbara Kasten, Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York, NY 2004 Barbara Kasten, Tampa Gallery of Photography, Tampa, FL Barbara Kasten, Gallery Luisotti, Santa Monica, CA 2002 Art Museum, University of Memphis, TN 2001 Barbara Kasten, Gallery Luisotti, Santa Monica, CA 2000 Small Works Gallery, Las Vegas, NV 1999 John Weber Gallery, New York, NY Gallery Luisotti, Bergamot Station, Santa Monica, CA 1998 Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York, NY 1997 Small Works Gallery, Las Vegas, NV 1996 Gallery Luisotti, Bergamot Station, Santa Monica, CA Frederick Spratt Gallery, San Jose, CA Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York, NY Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 1995 Contemporary Art Center, Vilnius, Lithuania 488 Ellis Street San Francisco, CA 94102 415.255.9508 jessicasilvermangallery.com Parchman Stremmel, San Antonio, TX 1993 Place Sazaby/Gallery RAM, Los Angeles, CA 1992 d.p.