Marginality and the Films of Hal Hartley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![New York / New York Film Festival, September 23 - October 9, 1994]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9802/new-york-new-york-film-festival-september-23-october-9-1994-29802.webp)

New York / New York Film Festival, September 23 - October 9, 1994]

Document generated on 09/29/2021 7:21 p.m. ETC New York New York Film Festival, September 23 - October 9, 1994 Steven Kaplan La critique d’art : enjeux actuels 1 Number 29, February–May 1995 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/35725ac See table of contents Publisher(s) Revue d'art contemporain ETC inc. ISSN 0835-7641 (print) 1923-3205 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Kaplan, S. (1995). Review of [New York / New York Film Festival, September 23 - October 9, 1994]. ETC, (29), 23–27. Tous droits réservés © Revue d'art contemporain ETC inc., 1995 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ nm/AiMiiEi NEW YORK New York Film Festival, September 23 - October 9,1994 ike the universe at large, film festivals often find the invidious structure of white overseer (coach, recruiter) it reassuring to start up with a big bang. The recent feeding off the talents and aspirations of a black underclass. 32nd edition of the New York Film Festival opened As Arthur Agee and William Gates progress from the with the explosive Pulp Fiction, fresh from its hood to a lily white suburban Catholic school (a basketball success at Cannes, continuing the virtual powerhouse which graduated Isiah Thomas) and hence to Ldeification of writer-director Quentin Tarantino among college, we are aware of the sacrifices they and their the hip media establishment, and poising him for entry families make, the difficulties of growing up black and into a wider marketplace. -

2009 Sundance Film Festival Announces Films in Competition

Media Contacts: For Immediate Release Brooks Addicott, 435.658.3456 December 3, 2008 [email protected] Amy McGee, 310.492.2333 [email protected] 2009 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES FILMS IN COMPETITION Festival Celebrates 25 Years of Independent Filmmaking and Cinematic Storytelling Park City, UT—Sundance Institute announced today the lineup of films selected to screen in the U.S. and World Cinema Dramatic and Documentary Competitions for the 25th Sundance Film Festival. In addition to the four Competition categories, the Festival presents films in five out-of-competition sections to be announced tomorrow. The 2009 Sundance Film Festival runs January 15-25 in Park City, Salt Lake City, Ogden, and Sundance, Utah. The complete list of films is available at www.sundance.org/festival. "This year's films are not narrowly defined. Instead we have a blurring of genres, a crossing of boundaries: geographic, generational, socio-economic and the like," said Geoffrey Gilmore, Director, Sundance Film Festival. "The result is both an exhilarating and emotive Festival in which traditional mythologies are suspended, discoveries are made, and creative storytelling is embraced." "Audiences may be surprised by how much emotion this year's films evoke," said John Cooper, Director of Programming, Sundance Film Festival. "We are seeing the next evolution of the independent film movement where films focus on storytelling with a sense of connection and purpose." For the 2009 Sundance Film Festival, 118 feature-length films were selected including 88 world premieres, 18 North American premieres, and 4 U.S. premieres representing 21 countries with 42 first-time filmmakers, including 28 in competition. -

An Lkd Films Production Presents

AN LKD FILMS PRODUCTION PRESENTS: RUNNING TIME.......................... 96 MIN GENRE ........................................ CRIME/DRAMA RATING .......................................NOT YET RATED YEAR............................................ 2015 LANGUAGE................................. ENGLISH COUNTRY OF ORIGIN ................ UNITED STATES FORMAT ..................................... 1920x1080, 23.97fps, 16:9, SounD 5.1 LINKS .......................................... Website: www.delinquentthemovie.com Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Delinquentthefilm/ IMDB: http://www.imDb.com/title/tt4225478/ Instagram: @delinquentmovie Hashtag: #delinquentmovie, #delinquentfilm SYNOPSIS The principal is itching to kick Joey out of high school, anD Joey can’t wait to get out. All he wants is to work for his father, a tree cutter by day anD the leader of a gang of small-time thieves by night in rural Connecticut. So when Joey’s father asks him to fill in as a lookout, Joey is thrilleD until a routine robbery goes very wrong. Caught between loyalties to family anD a chilDhood frienD in mourning. Joey has to deal with paranoiD accomplices, a criminal investigation, anD his own guilt. What kinD of man does Joey want to be, anD what does he owe to the people he loves? DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT My home state of Connecticut is depicteD in Television anD Film as the lanD of the wealthy anD privileged: country clubs, yachts, anD salmon coloreD polo shirts galore. Although many of these elements do exist, there is another siDe of Connecticut that is not often seen. It features blue-collar workers, troubleD youth, anD families living on the fringes. I was raiseD in WooDbury, a small town in LitchfielD Country that restricteD commercial businesses from operating within its borders. WooDbury haD a large disparity in its resiDent’s householD income anD over one hundreD antique shops that lineD the town’s “Main St.” I grew up in the rural part of town where my house shareD a property with my father’s plant business. -

Coldplay? 2016 CILL Season Begins 2016 Primary Election Results: So Goes City Island

Periodicals Paid at Bronx, N.Y. USPS 114-590 Volume 45 Number 4 May 2016 One Dollar Coldplay? 2016 CILL Season Begins By VIRGINIA DANNEGGER and KAREN NANI ria Piri, concession stand managers Jim and singlehandedly did the job of several and Sue Goonan, and equipment manager people. Even though his boys aged out of Lou Lomanaco. Several of these board the league, John still dedicates his time to members have served multiple terms on the help.” He presented John with a framed board. CILL jersey and a plaque in appreciation Mr. Esposito gave special thanks to for his support of the league and the City Photos by RICK DeWITT the outgoing president, John Tomsen, Island community. It was a chilly start to the 2016 Little League season on April 9, but the baseball tradi- who threw out the first pitch. “John has “As many of you know, volunteering tion dating back to 1900 is alive and warm on City Island. There are major, minor and time is a family commitment. Whether it t-ball teams competing once again this season. The ceremonial first pitch was thrown been president of the CILL since 2009 by outgoing president John Tomsen, who was also awarded a framed jersey by the Continued on page 19 new league president, Dom Esposito (right, top photo). New York State Assemblyman Michael Benedetto joined Catherine Ambrosini, Mr. Esposito and Mr. Tomsen (second photo, l. to r.) for the season opener. The American Legion color guard bearers led the teams in the “Star Spangled Banner.” As the weather warms up, head down to Ambro- 2016 Primary Election Results: sini Field next to P.S. -

Café Society

Presents CAFÉ SOCIETY A film by Woody Allen (96 min., USA, 2016) Language: English Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith Star PR 1352 Dundas St. West Tel: 416-488-4436 Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1Y2 Fax: 416-488-8438 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com @MongrelMedia MongrelMedia CAFÉ SOCIETY Starring (in alphabetical order) Rose JEANNIE BERLIN Phil STEVE CARELL Bobby JESSE EISENBERG Veronica BLAKE LIVELY Rad PARKER POSEY Vonnie KRISTEN STEWART Ben COREY STOLL Marty KEN STOTT Co-starring (in alphabetical order) Candy ANNA CAMP Leonard STEPHEN KUNKEN Evelyn SARI LENNICK Steve PAUL SCHNEIDER Filmmakers Writer/Director WOODY ALLEN Producers LETTY ARONSON, p.g.a. STEPHEN TENENBAUM, p.g.a. EDWARD WALSON, p.g.a. Co-Producer HELEN ROBIN Executive Producers ADAM B. STERN MARC I. STERN Executive Producer RONALD L. CHEZ Cinematographer VITTORIO STORARO AIC, ASC Production Designer SANTO LOQUASTO Editor ALISA LEPSELTER ACE Costume Design SUZY BENZINGER Casting JULIET TAYLOR PATRICIA DiCERTO 2 CAFÉ SOCIETY Synopsis Set in the 1930s, Woody Allen’s bittersweet romance CAFÉ SOCIETY follows Bronx-born Bobby Dorfman (Jesse Eisenberg) to Hollywood, where he falls in love, and back to New York, where he is swept up in the vibrant world of high society nightclub life. Centering on events in the lives of Bobby’s colorful Bronx family, the film is a glittering valentine to the movie stars, socialites, playboys, debutantes, politicians, and gangsters who epitomized the excitement and glamour of the age. Bobby’s family features his relentlessly bickering parents Rose (Jeannie Berlin) and Marty (Ken Stott), his casually amoral gangster brother Ben (Corey Stoll); his good-hearted teacher sister Evelyn (Sari Lennick), and her egghead husband Leonard (Stephen Kunken). -

Filmprogramm Oktober 2019 Rex Tone →3 Hal Hartley

Filmprogramm Oktober 2019 Rex Tone →3 Hal Hartley: Pionier des Independent-Films →4 REX Kids →13 Premieren: For Sama / Aquarela →15 So Long, My Son / Welcome to Sodom →19 Easy Love →20 Agenda →16/17 10 →21 Festivalfilme / Rex nuit Filmgeschichte →22 Berner filmPremiere →24 19 100 Jahre Bauhaus →25 Uncut / Kino und Theater →26/27 Shnit im Rex →28 www.rexbern.ch Editorial Von Thomas Allenbach Die Behauptung mag verwegen klingen, sie sei trotzdem gewagt: Im Okto- ber können Sie im REX den Film mit der besten Tanzszene der 1990er-Jahre sehen. Pulp Fiction? The Big Lebowski? Scent of a Woman? Sollten Sie unser Programm nach diesen Titeln durchforsten, werden Sie nicht fündig. Der Film heisst Simple Men, gedreht hat ihn der US-Amerikaner Hal Hartley, und der Song dazu stammt von Sonic Youth («Cool Thing» vom Album «Goo»). Falls Ihre Neugier geweckt ist: Die Szene können Sie sich auf Youtube Hier kommt die Nacht: anschauen (www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vgb8CyrgppI). Ich bin mir ziem- In der DJ-Reihe REXtone lich sicher, dass Sie danach unbedingt den ganzen Film sehen wollen – und spielen einmal im Monat ausgewählte DJs Obskuri- nach Simple Men gleich noch alle anderen Filme des Regisseurs, der in den täten, Raritäten und 1990er-Jahren zu den Helden des Independent-Kinos zählte und um den Popularitäten aus ihren es nach der Jahrtausendwende still geworden ist. Was hat Hartley seither weiten Archiven. Songs, die eine Einladung an die gemacht? Er ist unter anderem dabei, sich die Rechte an seinen Filmen Geselligkeit und Neugier- zurückzukaufen, diese zu restaurieren und neu zu untertiteln und sich so de sind und die zuweilen die Kontrolle über sein Oeuvre zu sichern. -

Sunshine State

SUNSHINE STATE A FILM BY JOHN SAYLES A Sony Pictures Classics Release 141 Minutes. Rated PG-13 by the MPAA East Coast East Coast West Coast Distributor Falco Ink. Bazan Entertainment Block-Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Shannon Treusch Evelyn Santana Melody Korenbrot Carmelo Pirrone Erin Bruce Jackie Bazan Ziggy Kozlowski Marissa Manne 850 Seventh Avenue 110 Thorn Street 8271 Melrose Avenue 550 Madison Avenue Suite 1005 Suite 200 8 th Floor New York, NY 10019 Jersey City, NJ 07307 Los Angeles, CA 9004 New York, NY 10022 Tel: 212-445-7100 Tel: 201 656 0529 Tel: 323-655-0593 Tel: 212-833-8833 Fax: 212-445-0623 Fax: 201 653 3197 Fax: 323-655-7302 Fax: 212-833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com CAST MARLY TEMPLE................................................................EDIE FALCO DELIA TEMPLE...................................................................JANE ALEXANDER FURMAN TEMPLE.............................................................RALPH WAITE DESIREE PERRY..................................................................ANGELA BASSETT REGGIE PERRY...................................................................JAMES MCDANIEL EUNICE STOKES.................................................................MARY ALICE DR. LLOYD...........................................................................BILL COBBS EARL PICKNEY...................................................................GORDON CLAPP FRANCINE PICKNEY.........................................................MARY -

Film Appreciation Wednesdays 6-10Pm in the Carole L

Mike Traina, professor Petaluma office #674, (707) 778-3687 Hours: Tues 3-5pm, Wed 2-5pm [email protected] Additional days by appointment Media 10: Film Appreciation Wednesdays 6-10pm in the Carole L. Ellis Auditorium Course Syllabus, Spring 2017 READ THIS DOCUMENT CAREFULLY! Welcome to the Spring Cinema Series… a unique opportunity to learn about cinema in an interdisciplinary, cinematheque-style environment open to the general public! Throughout the term we will invite a variety of special guests to enrich your understanding of the films in the series. The films will be preceded by formal introductions and followed by public discussions. You are welcome and encouraged to bring guests throughout the term! This is not a traditional class, therefore it is important for you to review the course assignments and due dates carefully to ensure that you fulfill all the requirements to earn the grade you desire. We want the Cinema Series to be both entertaining and enlightening for students and community alike. Welcome to our college film club! COURSE DESCRIPTION This course will introduce students to one of the most powerful cultural and social communications media of our time: cinema. The successful student will become more aware of the complexity of film art, more sensitive to its nuances, textures, and rhythms, and more perceptive in “reading” its multilayered blend of image, sound, and motion. The films, texts, and classroom materials will cover a broad range of domestic, independent, and international cinema, making students aware of the culture, politics, and social history of the periods in which the films were produced. -

Dead Zone Back to the Beach I Scored! the 250 Greatest

Volume 10, Number 4 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies and Television FAN MADE MONSTER! Elfman Goes Wonky Exclusive interview on Charlie and Corpse Bride, too! Dead Zone Klimek and Heil meet Romero Back to the Beach John Williams’ Jaws at 30 I Scored! Confessions of a fi rst-time fi lm composer The 250 Greatest AFI’s Film Score Nominees New Feature: Composer’s Corner PLUS: Dozens of CD & DVD Reviews $7.95 U.S. • $8.95 Canada �������������������������������������������� ����������������������� ���������������������� contents ���������������������� �������� ����� ��������� �������� ������ ���� ���������������������������� ������������������������� ��������������� �������������������������������������������������� ����� ��� ��������� ����������� ���� ������������ ������������������������������������������������� ����������������������������������������������� ��������������������� �������������������� ���������������������������������������������� ����������� ����������� ���������� �������� ������������������������������� ���������������������������������� ������������������������������������������ ������������������������������������� ����� ������������������������������������������ ��������������������������������������� ������������������������������� �������������������������� ���������� ���������������������������� ��������������������������������� �������������� ��������������������������������������������� ������������������������� �������������������������������������������� ������������������������������ �������������������������� -

Somebody up There Likes Me

TRIBECA FILM in partnership with AMERICAN EXPRESS presents a FALIRO HOUSE and M-13 PICTURES presentation a BOB BYINGTON film SOMEBODY UP THERE LIKES ME Run Time: 75 Minutes Rating: Not Rated Available On Demand: March 12, 2013 Select Theatrical release March 8 Chicago Music Box March 15 Los Angeles Cinefamily March 22 San Francisco Roxie Theater March 29 Denver Denver Film March 29 Brooklyn BAM April 5 Austin Violet Crown Distributor: Tribeca Film 375 Greenwich Street New York, NY 10011 Jennifer Holiner ID-PR 212-941-2038 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Starring Keith Poulson as Max Nick Offerman as Sal Jess Weixler as Lyla Stephanie Hunt as Clarissa Marshall Bell as Lyla's Dad Jonathan Togo as Adult Lyle Kate Lyn Sheil as Ex-Wife Ted Beck as Steakhouse Patron and Homeless Man Anna Margaret Hollyman as Paula Chris Doubek as Businessman Bob Schneider as Wedding Singer Alex Ross Perry as First Customer Gabriel Keller as Lyle Age 5 Ian Graffunder as Lyle Age 10 Jake Lewis as Lyle Age 15 with Kevin Corrigan as Memorial Man and Megan Mullally as Therapist SYNOPSIS Bob Byington’s smart, subversive comedy skips through 35 years in the life of Max Youngman (Keith Poulson), his best (and only) friend Sal (Nick Offerman, “Parks and Recreation”), and the woman they both adore (Jess Weixler, Teeth). As they stumble in and out of hilariously misguided relationships — strung together with animated vignettes by Bob Sabiston (A Scanner Darkly) and an original score by Vampire Weekend’s Chris Baio — Max never ages, holding on to a mysterious briefcase that may or may not contain the secret to life. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 86Th Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 86TH ACADEMY AWARDS ABOUT TIME Notes Domhnall Gleeson. Rachel McAdams. Bill Nighy. Tom Hollander. Lindsay Duncan. Margot Robbie. Lydia Wilson. Richard Cordery. Joshua McGuire. Tom Hughes. Vanessa Kirby. Will Merrick. Lisa Eichhorn. Clemmie Dugdale. Harry Hadden-Paton. Mitchell Mullen. Jenny Rainsford. Natasha Powell. Mark Healy. Ben Benson. Philip Voss. Tom Godwin. Pal Aron. Catherine Steadman. Andrew Martin Yates. Charlie Barnes. Verity Fullerton. Veronica Owings. Olivia Konten. Sarah Heller. Jaiden Dervish. Jacob Francis. Jago Freud. Ollie Phillips. Sophie Pond. Sophie Brown. Molly Seymour. Matilda Sturridge. Tom Stourton. Rebecca Chew. Jon West. Graham Richard Howgego. Kerrie Liane Studholme. Ken Hazeldine. Barbar Gough. Jon Boden. Charlie Curtis. ADMISSION Tina Fey. Paul Rudd. Michael Sheen. Wallace Shawn. Nat Wolff. Lily Tomlin. Gloria Reuben. Olek Krupa. Sonya Walger. Christopher Evan Welch. Travaris Meeks-Spears. Ann Harada. Ben Levin. Daniel Joseph Levy. Maggie Keenan-Bolger. Elaine Kussack. Michael Genadry. Juliet Brett. John Brodsky. Camille Branton. Sarita Choudhury. Ken Barnett. Travis Bratten. Tanisha Long. Nadia Alexander. Karen Pham. Rob Campbell. Roby Sobieski. Lauren Anne Schaffel. Brian Charles Johnson. Lipica Shah. Jarod Einsohn. Caliaf St. Aubyn. Zita-Ann Geoffroy. Laura Jordan. Sarah Quinn. Jason Blaj. Zachary Unger. Lisa Emery. Mihran Shlougian. Lynne Taylor. Brian d'Arcy James. Leigha Handcock. David Simins. Brad Wilson. Ryan McCarty. Krishna Choudhary. Ricky Jones. Thomas Merckens. Alan Robert Southworth. ADORE Naomi Watts. Robin Wright. Xavier Samuel. James Frecheville. Sophie Lowe. Jessica Tovey. Ben Mendelsohn. Gary Sweet. Alyson Standen. Skye Sutherland. Sarah Henderson. Isaac Cocking. Brody Mathers. Alice Roberts. Charlee Thomas. Drew Fairley. Rowan Witt. Sally Cahill. -

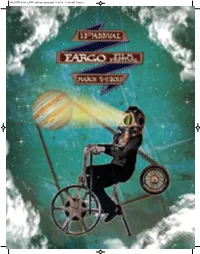

FFF 2004 Program.Qxd 2/20/13 11:18 AM Page 1 2013 FFF8.5X11 Fff2004program.Qxd2/20/1311:18Ampage2 1

2013 FFF 8.5x11_FFF 2004 program.qxd 2/20/13 11:18 AM Page 1 2013 FFF 8.5x11_FFF 2004 program.qxd 2/20/13 11:18 AM Page 2 DAN FRANCIS PHOTOGRAPHY 1 2013 FFF 8.5x11_FFF 2004 program.qxd 2/20/13 11:18 AM Page 3 ONCE UPON A TIME, MOTION PICTURES WERE ENORMOUS THINGS. Massive amounts of 35mm film were packed neatly in unwieldy padlocked metal cans and sent to a world’s worth of neighborhood cinemas. During my tenure at a local multiplex, a particularly long movie about a boy wizard resulted in a particularly massive film print. I managed to get this print halfway up a particularly steep staircase before tumbling bow-tie first down to what I feared was my doom but was, in fact, a conveniently placed pile of industrial sized bags of Orville Redenbacher. After that, I left it to our fearless projectionists to struggle them up the stairs to dimly lit projection booths. There, hunched over miles of celluloid, they would work into the wee hours of the morning – steady hands and bleary eyes assembling a new adventure. Such was the weight of storytelling. And the enormity of it made sense to me. Should one be able to lose the life and times of Charles Foster Kane if it slides down into that little space between the entertainment center and the wall? Emily Beck FARGO THEATRE Should the battle against an evil galactic empire be shipped in a standard packing envelope lined with those delicious little bubbles? Executive Director Isn’t it only fitting that the epic journey to return The One Ring (back to the fiery chasm from whence it came) be so enormous it could topple a teenager in an usher’s tuxedo made entirely of polyester? But the world turned.