A Pilgrim's Guide to Mount Athos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Monasteries

Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Monasteries Atlas of Whether used as a scholarly introduction into Eastern Christian monasticism or researcher’s directory or a travel guide, Alexei Krindatch brings together a fascinating collection of articles, facts, and statistics to comprehensively describe Orthodox Christian Monasteries in the United States. The careful examina- Atlas of American Orthodox tion of the key features of Orthodox monasteries provides solid academic frame for this book. With enticing verbal and photographic renderings, twenty-three Orthodox monastic communities scattered throughout the United States are brought to life for the reader. This is an essential book for anyone seeking to sample, explore or just better understand Orthodox Christian monastic life. Christian Monasteries Scott Thumma, Ph.D. Director Hartford Institute for Religion Research A truly delightful insight into Orthodox monasticism in the United States. The chapters on the history and tradition of Orthodox monasticism are carefully written to provide the reader with a solid theological understanding. They are then followed by a very human and personal description of the individual US Orthodox monasteries. A good resource for scholars, but also an excellent ‘tour guide’ for those seeking a more personal and intimate experience of monasticism. Thomas Gaunt, S.J., Ph.D. Executive Director Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA) This is a fascinating and comprehensive guide to a small but important sector of American religious life. Whether you want to know about the history and theology of Orthodox monasticism or you just want to know what to expect if you visit, the stories, maps, and directories here are invaluable. -

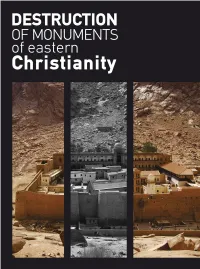

Monuments.Pdf

© 2017 INTERPARLIAMENTARY ASSEMBLY ON ORTHODOXY ISBN 978-960-560 -139 -3 Front cover page photo Sacred Monastery of Mount Sinai, Egypt Back cover page photo Saint Sophia’s Cathedral, Kiev, Ukrania Cover design Aristotelis Patrikarakos Book artwork Panagiotis Zevgolis, Graphic Designer, HELLENIC PARLIAMENT | Publications & Printing Directorate Editing George Parissis, HELLENIC PARLIAMENT | International Affairs Directorate Maria Bakali, I.A.O. Secretariat Lily Vardanyan, I.A.O. Secretariat Printing - Bookbinding HELLENIC PARLIAMENT | Publications & Printing Directorate Οι πληροφορίες των κειμένων παρέχονται από τους ίδιους τους διαγωνιζόμενους και όχι από άλλες πηγές The information of texts is provided by contestants themselves and not from other sources ΠΡΟΛΟΓΟΣ Η προστασία της παγκόσμιας πολιτιστικής κληρονομιάς, υποδηλώνει την υψηλή ευθύνη της κάθε κρατικής οντότητας προς τον πολιτισμό αλλά και ενδυναμώνει τα χαρακτηριστικά της έννοιας “πολίτης του κόσμου” σε κάθε σύγχρονο άνθρωπο. Η προστασία των θρησκευτικών μνημείων, υποδηλώνει επί πλέον σεβασμό στον Θεό, μετοχή στον ανθρώ - πινο πόνο και ενθάρρυνση της ανθρώπινης χαράς και ελπίδας. Μέσα σε κάθε θρησκευτικό μνημείο, περι - τοιχίζεται η ανθρώπινη οδύνη αιώνων, ο φόβος, η προσευχή και η παράκληση των πονεμένων και αδικημένων της ιστορίας του κόσμου αλλά και ο ύμνος, η ευχαριστία και η δοξολογία προς τον Δημιουργό. Σεβασμός προς το θρησκευτικό μνημείο, υποδηλώνει σεβασμό προς τα συσσωρευμένα από αιώνες αν - θρώπινα συναισθήματα. Βασισμένη σε αυτές τις απλές σκέψεις προχώρησε η Διεθνής Γραμματεία της Διακοινοβουλευτικής Συνέ - λευσης Ορθοδοξίας (Δ.Σ.Ο.) μετά από απόφαση της Γενικής της Συνέλευσης στην προκήρυξη του δεύτερου φωτογραφικού διαγωνισμού, με θέμα: « Καταστροφή των μνημείων της Χριστιανικής Ανατολής ». Επι πλέον, η βούληση της Δ.Σ.Ο., εστιάζεται στην πρόθεσή της να παρουσιάσει στο παγκόσμιο κοινό, τον πολιτισμικό αυτό θησαυρό της Χριστιανικής Ανατολής και να επισημάνει την ανάγκη μεγαλύτερης και ου - σιαστικότερης προστασίας του. -

The Mural Paintings of Protaton Church from Mount Athos

European Journal of Science and Theology, February 2020, Vol.16, No.1, 199-206 _______________________________________________________________________ THE MURAL PAINTINGS OF PROTATON CHURCH FROM MOUNT ATHOS Petru Sofragiu* Alexandru Ioan Cuza University of Iaşi, Faculty of Orthodox Theology, 9 Cloșca, Iasi, 700065, Romania (Received 24 September 2019, revised 13 November 2019) Abstract This paper focuses on the study of the Church of the Protaton in Karyes, the most representative monument of Holy Mount Athos. Its mural paintings, which show examples of Byzantine Art and date back to the Paleologan period (the 19th century), have been preserved until today. They were attributed to Manuel Panselinos, the founder of the Macedonian School of painting, who also frescoed numerous churches in Macedonia and Medieval Serbia. The analysis of the stylistic elements, iconographic themes and their theological significance has surely given us the opportunity to take a deeper insight into the artistic background of this amazing painter who mastered the monumental compositions of the Church of the Protaton. The study aims at highlighting both the similarities and the differences in Panselinos’ masterpieces and the monuments decorated by the proud disciples of this top master in Thessaloniki, who remains an inexhaustible source of inspiration for future generations of artists. Keywords: Protaton, Karyes, Paleologan period, Panselinos 1. Introduction - brief history of the Protaton Church Near the centre of Athos Peninsula, it is located city of Karyes, which is the capital of Mount Athos. Founded in the 9th century, its name derives from the walnut trees (karyai), which abound in this region even from Antiquity, where the sanctuary of goddess Artemis is also located [1]. -

KARYES Lakonia

KARYES Lakonia The Caryatides Monument full of snow News Bulletin Number 20 Spring 2019 KARYATES ASSOCIATION: THE ANNUAL “PITA” DANCE THE BULLETIN’S SPECIAL FEATURES The 2019 Association’s Annual Dance was successfully organized. One more time many compartiots not only from Athens, but also from other CONTINUE cities and towns of Greece gathered together. On Sunday February 10th Karyates enjoyed a tasteful meal and danced at the “CAPETANIOS” hall. Following the positive response that our The Sparta mayor mr Evagellos first special publication of the history of Valliotis was also present and Education in Karyes had in our previous he addressed to the Karyates issue, this issue continues the series of congratulating the Association tributes to the history of our country. for its efforts. On the occasion of the Greek National After that, the president of the Independence Day on March 25th, we Association mr Michael publish a new tribute to the Repoulis welcome all the participation of Arachovitians/Karyates compatriots and present a brief in the struggle of the Greek Nation to report for the year 2018 and win its freedom from the Ottoman the new year’s action plan. slavery. The board members of the Karyates Association Mr. Valliotis, Sparta Mayor At the same time, with the help of Mr. The Vice President of the Association Ms Annita Gleka-Prekezes presented her new book “20th Century Stories, Traditions, Narratives from the Theodoros Mentis, we publish a second villages of Northern Lacedaemon” mentioning that all the revenues from its sells will contribute for the Association’s actions. special reference to the Karyes Dance Group. -

Preserving & Promoting Understanding of the Monastic

We invite you to help the MOUNT ATHOS Preserving & Promoting FOUNDATION OF AMERICA Understanding of the in its efforts. Monastic Communities You can share in this effort in two ways: of Mount Athos 1. DONATE As a 501(c)(3), MAFA enables American taxpayers to make tax-deductible gifts and bequests that will help build an endowment to support the Holy Mountain. 2. PARTICIPATE Become part of our larger community of patrons, donors, and volunteers. Become a Patron, OUr Mission Donor, or Volunteer! www.mountathosfoundation.org MAFA aims to advance an understanding of, and provide benefit to, the monastic community DONATIONS BY MAIL OR ONLINE of Mount Athos, located in northeastern Please make checks payable to: Greece, in a variety of ways: Mount Athos Foundation of America • and RESTORATION PRESERVATION Mount Athos Foundation of America of historic monuments and artifacts ATTN: Roger McHaney, Treasurer • FOSTERING knowledge and study of the 2810 Kelly Drive monastic communities Manhattan, KS 66502 • SUPPORTING the operations of the 20 www.mountathosfoundation.org/giving monasteries and their dependencies in times Questions contact us at of need [email protected] To carry out this mission, MAFA works cooperatively with the Athonite Community as well as with organizations and foundations in the United States and abroad. To succeed in our mission, we depend on our patrons, donors, and volunteers. Thank You for Your Support The Holy Mountain For more than 1,000 years, Mount Athos has existed as the principal pan-Orthodox, multinational center of monasticism. Athos is unique within contemporary Europe as a self- governing region claiming the world’s oldest continuously existing democracy and entirely devoted to monastic life. -

An Essay in Universal History

AN ESSAY IN UNIVERSAL HISTORY From an Orthodox Christian Point of View VOLUME VI: THE AGE OF MAMMON (1945 to 1992) PART 2: from 1971 to 1992 Vladimir Moss © Copyright Vladimir Moss, 2018: All Rights Reserved 1 The main mark of modern governments is that we do not know who governs, de facto any more than de jure. We see the politician and not his backer; still less the backer of the backer; or, what is most important of all, the banker of the backer. J.R.R. Tolkien. It is time, it is the twelfth hour, for certain of our ecclesiastical representatives to stop being exclusively slaves of nationalism and politics, no matter what and whose, and become high priests and priests of the One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church. Fr. Justin Popovich. The average person might well be no happier today than in 1800. We can choose our spouses, friends and neighbours, but they can choose to leave us. With the individual wielding unprecedented power to decide her own path in life, we find it ever harder to make commitments. We thus live in an increasingly lonely world of unravelling commitments and families. Yuval Noah Harari, (2014). The time will come when they will not endure sound doctrine, but according to their own desires, because they have itching ears, will heap up for themselves teachers, and they will turn their ears away from the truth, and be turned aside to fables. II Timothy 4.3-4. People have moved away from ‘religion’ as something anchored in organized worship and systematic beliefs within an institution, to a self-made ‘spirituality’ outside formal structures, which is based on experience, has no doctrine and makes no claim to philosophical coherence. -

Athos Gregory Ch

8 Athos Gregory Ch. 6_Athos Gregory Ch. 6 5/15/14 12:53 PM Page 154 TWENTIETH-CENTURY ATHOS it of course came the first motorized vehicles ever seen on Athos. 2 Such con - cessions to modernization were deeply shocking to many of the monks. And they were right to suspect that the trend would not stop there. SEEDS Of RENEWAl Numbers of monks continued to fall throughout the 960s and it was only in the early 970s that the trend was finally arrested. In 972 the population rose from ,5 to ,6—not a spectacular increase, but nevertheless the first to be recorded since the turn of the century. Until the end of the century the upturn was maintained in most years and the official total in 2000 stood at just over ,600. The following table shows the numbers for each monastery includ - ing novices and those living in the dependencies: Monastery 972 976 97 90 92 96 9 990 992 2000 lavra 0 55 25 26 29 09 7 5 62 Vatopedi 7 65 60 5 50 55 50 75 2 Iviron 5 6 52 52 5 5 5 6 6 7 Chilandar 57 6 69 52 5 6 60 75 Dionysiou 2 7 5 5 56 59 59 59 50 5 Koutloumousiou 6 6 66 57 0 75 7 7 77 95 Pantokrator 0 7 6 6 62 69 57 66 50 70 Xeropotamou 0 26 22 7 6 7 0 0 Zographou 2 9 6 2 5 20 Dochiariou 2 29 2 2 27 Karakalou 2 6 20 6 6 9 26 7 Philotheou 2 0 6 66 79 2 79 7 70 Simonopetra 2 59 6 60 72 79 7 0 7 7 St Paul’s 95 9 7 7 6 5 9 5 0 Stavronikita 7 5 0 0 0 2 5 Xenophontos 7 26 9 6 7 50 57 6 Grigoriou 22 0 57 6 7 62 72 70 77 6 Esphigmenou 9 5 0 2 56 0 Panteleimonos 22 29 0 0 2 2 5 0 5 Konstamonitou 6 7 6 22 29 20 26 0 27 26 Total ,6 ,206 ,27 ,9 ,275 ,25 ,255 ,290 ,7 ,60 These figures tell us a great deal about the revival and we shall examine 2 When Constantine Cavarnos visited Chilandar in 95, however, he was informed by fr Domitian, ‘We now have a tractor, too. -

Manolis G. Varvounis * – Nikos Rodosthenous Religious

Manolis G. Varvounis – Nikos Rodosthenous Religious Traditions of Mount Athos on Miraculous Icons of Panagia (The Mother of God) At the monasteries and hermitages of Mount Athos, many miraculous icons are kept and exhibited, which are honored accordingly by the monks and are offered for worship to the numerous pilgrims of the holy relics of Mount Athos.1 The pil- grims are informed about the monastic traditions of Mount Athos regarding these icons, their origin, and their miraculous action, during their visit to the monasteries and then they transfer them to the world so that they are disseminated systemati- cally and they can become common knowledge of all believers.2 In this way, the traditions regarding the miraculous icons of Mount Athos become wide-spread and are considered an essential part of religious traditions not only of the Greek people but also for other Orthodox people.3 Introduction Subsequently, we will examine certain aspects of these traditions, based on the literature, notably the recent work on the miraculous icons in the monasteries of Mount Athos, where, except for the archaeological and the historical data of these specific icons, also information on the wonders, their origin and their supernatural action over the centuries is captured.4 These are information that inspired the peo- ple accordingly and are the basis for the formation of respective traditions and re- ligious customs that define the Greek folk religiosity. Many of these traditions relate to the way each icon ended up in the monastery where is kept today. According to the archetypal core of these traditions, the icon was thrown into the sea at the time of iconoclasm from a region of Asia Minor or the Near East, in order to be saved from destruction, and miraculously arrived at the monastery. -

Study Abroad Syllabus GE157 a Walk Across Greece

Study Abroad Syllabus GE157 A Walk Across Greece Description This course takes students on a journey across the country for a series of interactive excursions exploring the history of Greece through day hikes, walking tours and guided visits to regional museums, historical sites and famous monuments. Travelling from the Homeric epics of the Bronze Age to the 19th century War of Independence, students follow the vicissitudes of 5,000 years of history, covering over 1,000 kilometres of geography with peripatetic lectures and group discussions. Learning Outcomes At the end of this course, students will Exhibit an understanding of historical developments in Greece from ancient times to the present. Identify and discuss the monuments they will have visited and be able to recognize their stylistic attributes within the larger iconographic, historic, religious, and sociological contexts of the period they were created. Develop an understanding and appreciation for Hellenic culture and how it has shaped the development of Western thought, culture, and tradition. Method of Evaluation Assessment Area Percentage Pre-course reading and assignment 15% Attend class activities and actively participate in discussions 40% Deliver an post-course essay 25% Record reflections in a Travel Logue (or a Journal on preset themes) 20% during the trip and make a presentation based thereon Total 100% Policies and Procedures Attendance Policy: Class participation and attendance are an integral part of the University’s education policy: “Our mission requires of us that we pursue excellence in education…We are therefore committed to following the best practices of American higher education that encourage and require punctuality as well as attendance.” Plagiarism Policy: Students are responsible for performing academic tasks in such a way that honesty is not in question. -

CFHB 26 Manuel II Palaeologus Funeral Oration.Pdf

MANUEL PALAEOLOGUS FUNERAL ORATION CORPUS FONTIUM HISTORI-AE BYZANTINAE CONSILIO SOCIETATIS INTERNATIONAL IS STUD lIS BYZANTINIS PROVEHENDIS DESTINATAE EDITUM VOLUMEN XXVI MANUEL 11 PALAEOLOGUS FUNERAL ORATION ON HIS BROTHER THEODORE EDIDIT, ANGLlCE VERTlT ET ADNOTAVIT JULIANA CHRYSOSTOMIDES SERIES THESSALONICENSIS EDlDIT IOHANNES KARAYANNOPULOS APUD SOCIETATEM STUDIORUM BYZANTINORUM THESSALONICAE MCMLXXXV MANUEL 11 PALAEOLOGUS FUNERAL ORATION ON HIS BROTHER THEODORE INTRODUCTION, TEXT, TRANSLATION AND NOTES BY J. CHRYSOSTOMIDES ASSOCIATION FOR BYZANTINE RESEARCH THESSALONlKE 1985 l:TOIXEI00El:IA - EKTynnl:H 0ANAl:Hl: AATIN�ZHl:, E0N. AMYNHl: 38, THA. 221.529, 0El:l:AAONIKH ElL ANAMNHLIN n. Raymond-J. Loenertz a.p. NIKOAdov dJeJ..rpov Kai l1'7rpOC; TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Abbreviations ........................................... ix-xii List of Signs ................................................. xiii List of Illustrations ............................................ xiv Foreword ................................." ... ................. 3-4 Introduction ..........' ....." ......................... ....... 5-62 I. The Author ............................................... 5-13 n. Historical Introduction ..................................... 15-25 'nl. Text and Manuscripts ..................................... 27-62 A. Text ................................................... 27-31 B. Manuscripts ............................................. 32-42 . C. Relationship of the Manuscripts ......................... 43-53 D. Editions and Translations -

The Mt. Lykaion Excavation and Survey Project Survey and Excavation Lykaion Mt

excavating at the Birthplace of Zeus The Mt. Lykaion Excavation and Survey Project by david gilman romano and mary e. voyatzis www.penn.museum/expedition 9 Village of Ano Karyes on the eastern slopes of Mt. Lykaion. The Sanctuary of Zeus is above the village and beyond view of this photograph. in the 3rd century BCE, the Greek poet Callimachus wrote a Hymn to Zeus asking the ancient and most powerful Greek god whether he was born in Arcadia on Mt. Lykaion or in Crete on Mt. Ida. My soul is all in doubt, since debated is his birth. O Zeus, some say that you were born on the hills of Ida; others, O Zeus, say in Arcadia; did these or those, O Father lie? “Cretans are ever liars.” These two traditions relating to the birthplace of Zeus were clearly known in antiquity and have been transmitted to the modern day. It was one of the first matters that the village leaders in Ano Karyes brought to our attention when we arrived there in 2003. We came to discuss logistical support for our proposed project to initiate a new excavation and survey project at the nearby Sanctuary of Zeus. Situated high on the eastern slopes of Mt. Lykaion, Ano Karyes, with a winter population of 22, would become our base of operations, and the village leaders representing the Cultural Society of Ano Karyes would become our friends and collaborators in this endeavor. We were asked very directly if we could prove that Zeus was born on Mt. Lykaion. In addition, village leaders raised another historical matter related to the ancient reference by Pliny, a 1st century CE author, who wrote that the athletic festival at Mt. -

Managing-The-Heritage-Of-Mt-Athos

174 Managing the heritage of Mt Athos Thymio Papayannis1 Introduction Cypriot monastic communities (Tachi- aios, 2006). Yet all the monks on Mt The spiritual, cultural and natural herit- Athos are recognised as citizens of age of Mt Athos dates back to the end Greece residing in a self-governed part of the first millennium AD, through ten of the country (Kadas, 2002). centuries of uninterrupted monastic life, and is still vibrant in the beginning of Already in 885 Emperor Basil I de- the third millennium. The twenty Chris- clared Mt Athos as ‘…a place of monks, tian Orthodox sacred monasteries that where no laymen nor farmers nor cat- share the Athonite peninsula – in tle-breeders were allowed to settle’. Halkidiki to the East of Thessaloniki – During the Byzantine Period a number are quite diverse. Established during of great monasteries were established the Byzantine times, and inspired by in the area. The time of prosperity for the monastic traditions of Eastern Chris- the monasteries continued even in the tianity, they have developed through the early Ottoman Empire period. However, ages in parallel paths and even have the heavy taxation gradually inflicted different ethnic backgrounds with on them led to an economic crisis dur- Greek, Russian, Serbian, Bulgarian and 1 The views included in this paper are of its au- thor and do not represent necessarily those of < The approach to the Stavronikita Monastery. the Holy Community of Mt Athos. 175 Cape Arapis younger and well-educated monks (Si- deropoulos, 2000) whose number has Chilandariou been doubled during the past forty Esgmenou Ouranoupoli Cape Agios Theodori years.