Hearing the Silence: Finding the Middle Ground in the Spatial Humanities? Extracting and Comparing Perceived Silence and Tranquillity in the English Lake District

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Season 5 Article

N.B. IT IS RECOMMENDED THAT THE READER USE 2-PAGE VIEW (BOOK FORMAT WITH SCROLLING ENABLED) IN ACROBAT READER OR BROWSER. “EVEN’ING IT OUT – A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE LAST TWO YEARS OF “THE TWILIGHT ZONE” Television Series (minus ‘THE’)” A Study in Three Parts by Andrew Ramage © 2019, The Twilight Zone Museum. All rights reserved. Preface With some hesitation at CBS, Cayuga Productions continued Twilight Zone for what would be its last season, with a thirty-six episode pipeline – a larger count than had been seen since its first year. Producer Bert Granet, who began producing in the previous season, was soon replaced by William Froug as he moved on to other projects. The fifth season has always been considered the weakest and, as one reviewer stated, “undisputably the worst.” Harsh criticism. The lopsidedness of Seasons 4 and 5 – with a smattering of episodes that egregiously deviated from the TZ mold, made for a series much-changed from the one everyone had come to know. A possible reason for this was an abundance of rather disdainful or at least less-likeable characters. Most were simply too hard to warm up to, or at the very least, identify with. But it wasn’t just TZ that was changing. Television was no longer as new a medium. “It was a period of great ferment,” said George Clayton Johnson. By 1963, the idyllic world of the 1950s was disappearing by the day. More grittily realistic and reality-based TV shows were imminent, as per the viewing audience’s demand and it was only a matter of time before the curtain came down on the kinds of shows everyone grew to love in the 50s. -

A History of Rhythm, Metronomes, and the Mechanization of Musicality

THE METRONOMIC PERFORMANCE PRACTICE: A HISTORY OF RHYTHM, METRONOMES, AND THE MECHANIZATION OF MUSICALITY by ALEXANDER EVAN BONUS A DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2010 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of _____________________________________________________Alexander Evan Bonus candidate for the ______________________Doctor of Philosophy degree *. Dr. Mary Davis (signed)_______________________________________________ (chair of the committee) Dr. Daniel Goldmark ________________________________________________ Dr. Peter Bennett ________________________________________________ Dr. Martha Woodmansee ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ (date) _______________________2/25/2010 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. Copyright © 2010 by Alexander Evan Bonus All rights reserved CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES . ii LIST OF TABLES . v Preface . vi ABSTRACT . xviii Chapter I. THE HUMANITY OF MUSICAL TIME, THE INSUFFICIENCIES OF RHYTHMICAL NOTATION, AND THE FAILURE OF CLOCKWORK METRONOMES, CIRCA 1600-1900 . 1 II. MAELZEL’S MACHINES: A RECEPTION HISTORY OF MAELZEL, HIS MECHANICAL CULTURE, AND THE METRONOME . .112 III. THE SCIENTIFIC METRONOME . 180 IV. METRONOMIC RHYTHM, THE CHRONOGRAPHIC -

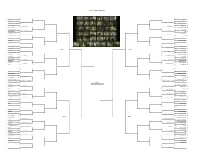

Favorite Twilight Zone Episodes.Xlsx

TITLE - VOTING BRACKETS First Round Second Round Sweet Sixteen Elite Eight Final Four Championship Final Four Elite Eight Sweet Sixteen Second Round First Round Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes 1 Time Enough at Last 57 56 Eye of the Beholder 1 Time Enough at Last Eye of the Beholder 32 The Fever 4 5 The Mighty Casey 32 16 A World of Difference 25 19 The Rip Van Winkle Caper 16 I Shot an Arrow into the Air A Most Unusual Camera 17 I Shot an Arrow into the Air 35 41 A Most Unusual Camera 17 8 Third from the Sun 44 37 The Howling Man 8 Third from the Sun The Howling Man 25 A Passage for Trumpet 16 Nervous22 Man in a Four Dollar Room 25 9 Love Live Walter Jameson 34 45 The Invaders 9 Love Live Walter Jameson The Invaders 24 The Purple Testament 25 13 Dust 24 5 The Hitch-Hiker 52 41 The After Hours 5 The Hitch-Hiker The After Hours 28 The Four of Us Are Dying 8 19 Mr. Bevis 28 12 What You Need 40 31 A World of His Own 12 What You Need A World of His Own 21 Escape Clause 19 28 The Lateness of the Hour 21 4 And When the Sky Was Opened 37 48 The Silence 4 And When the Sky Was Opened The Silence 29 The Chaser 21 11 The Mind and the Matter 29 13 A Nice Place to Visit 35 35 The Night of the Meek 13 A Nice Place to Visit The Night of the Meek 20 Perchance to Dream 24 24 The Man in the Bottle 20 Season 1 Season 2 6 Walking Distance 37 43 Nick of Time 6 Walking Distance Nick of Time 27 Mr. -

ANTHOLOGY of TEXT SCORES

ANTHOLOGY of TEXT SCORES Pauline Oliveros Foreword by Brian Pertl edited by Samuel Golter and Lawton Hall Anthology ofText Scores by Pauline Oliveros Compilation and editing by Samuel Golter Page layout, editing, graphics, and design by Lawton Hall Cover artwork by Nico Bovoso and Lawton Hall © 2013 Deep Listening Publications. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced by any means-graphic, electronic, or mechanical-including photocopying, recording, taping or by any information storage retrieval system without the written permission of the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles and reviews. Deep Listening Publications Deep Listening Institute, Ltd. 77 Cornell Street, Suite 303 Kingston, NY 12401 www.deeplistening.org ISBN: 978-1-889471-22-8 Printed in the United States of America TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword ................................................................................................................................. i Brian Pert! Preface .....................................................................................................................................v Pauline Oliveros Editor's Note ..........................................................................................................................vii Samuel Golter The Earthworm Also Sings ...................................................................................................... 1 A Composer's Guide to Deep Listening PERFORMANCE PIECESfor SOLOIS TS T riskaidekaphonia -

HOW to WATCH TELEVISION This Page Intentionally Left Blank HOW to WATCH TELEVISION

HOW TO WATCH TELEVISION This page intentionally left blank HOW TO WATCH TELEVISION EDITED BY ETHAN THOMPSON AND JASON MITTELL a New York University Press New York and London NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS New York and London www.nyupress.org © 2013 by Ethan Thompson and Jason Mittell All rights reserved References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data How to watch television / edited by Ethan Thompson and Jason Mittell. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8147-4531-1 (cl : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8147-6398-8 (pb : alk. paper) 1. Television programs—United States. 2. Television programs—Social aspects—United States. 3. Television programs—Political aspects—United States. I. Thompson, Ethan, editor of compilation. II. Mittell, Jason, editor of compilation. PN1992.3.U5H79 2013 791.45'70973—dc23 2013010676 New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books. Manufactured in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction: An Owner’s Manual for Television 1 Ethan Thompson and Jason Mittell I. TV Form: Aesthetics and Style 1 Homicide: Realism 13 Bambi L. Haggins 2 House: Narrative Complexity 22 Amanda D. -

Ödön Von Horváth's Volksstücke

Ödön von Horváth’s Volksstücke. Sounds and silences in dramaturgy and theatrical performance Alina Sofronie A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities and Languages Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences University of New South Wales November 2016 ORIGINALITY STATEMENT I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project’s design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged. Signed ………………………… Date ……………………………… i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank my supervisors, Dr Robert Buch, School of Humanities and Languages, Associate Professor Gerhard Fischer, School of Humanities and Languages, and Dr Meg Mumford, School of the Arts and Media, for the provision of their time, experience and advice. I have appreciated their constructive criticism and guidance during the development of this thesis. Throughout my candidature they have offered me support -

Human Sonic Permeability and the Practice of Cinema Sound Design Within Ecologies of Silences

Please do not remove this page Insounds : human sonic permeability and the practice of cinema sound design within ecologies of silences Delmotte, Isabelle https://researchportal.scu.edu.au/discovery/delivery/61SCU_INST:ResearchRepository/1267125620002368?l#1367374680002368 Delmotte, I. (2013). Insounds: human sonic permeability and the practice of cinema sound design within ecologies of silences [Southern Cross University]. https://researchportal.scu.edu.au/discovery/fulldisplay/alma991012821334302368/61SCU_INST:Research Repository Southern Cross University Research Portal: https://researchportal.scu.edu.au/discovery/search?vid=61SCU_INST:ResearchRepository [email protected] Open Downloaded On 2021/10/01 00:25:06 +1000 Please do not remove this page ‘Insounds’: Human sonic permeability and the practice of cinema sound design within ecologies of silences Isabelle Delmotte MFA Research (1st class Honours) (U.N.S.W) School of Arts and Social Sciences Media Studies Southern Cross University, NSW Exegesis supporting a multi-media exhibition entitled ‘Inaudible Visions, Oscillating Silences’ and submitted towards fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2013 Statement of Authorship I certify that the work presented in this thesis is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, original, except as acknowledged in the text, and that the material has not been submitted, either in whole or in part, for a degree at this or any other university. I acknowledge that I have read and understood the University’s rules, requirements, procedures and policy relating to my higher degree research award and to my thesis. I certify that I have complied with the rules, requirements, procedures and policy of the University. -

Wissnerupdatedcv8.24.2019

Reba A. Wissner, Ph.D. 1 Reba A. Wissner, Ph.D. 2940 Bouck Avenue Bronx, NY 10469-5211 718-974-3109 [email protected] EDUCATION Degrees 2012 Ph.D., Historical Musicology, Brandeis University Dissertation Title: “Of Gods, Myths, and Mortals: Francesco Cavalli’s L’Elena (1659)” Research Advisor: Eric Chafe Readers: Seth Coluzzi (Colgate University), Wendy Heller (Princeton University) 2008 M.F.A., Historical Musicology, Brandeis University 2005 B.A., cum laude, Music with Departmental Honors and Italian, Hunter College of the City University of New York Certificates 2019 (Expected) Graduate Certificate, Higher Education Administration, Northeastern University 16 credit hours in higher education law, finance, governance, operations, and curriculum and instructional design ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS Spring 2019 Adjunct Assistant Professor, Music History, Department of Music, Seton Hall University Fall 2017-Present Affiliated Faculty, Film and Media Studies Program, Rider University Fall 2016-Present Adjunct Assistant Professor, Music History and Theory, Steinhardt School, Department of Music and Performing Arts Professions, New York University Fall 2016-Present Adjunct Assistant Professor, Department of Music, School of Contemporary Arts, Ramapo College of New Jersey Fall 2015-Present Adjunct Assistant Professor, Department of Music Composition, History, and Theory, Westminster Choir College of Rider University Fall 2013-Present Adjunct Professor, Department of Music History, John J. Cali School of Music, Montclair State University Winter -

Annual Reports, Town of Acton, Massachusetts

1 3 wly? ACTON ANNUAL REPORT :;::. 1 97 OF GENERAL INTEREST Incorporated as a Town: July 3, 1735 Type of Government: Open Town Meeting-Selectmen-Town Manager. Location: Eastern Massachusetts, Middlesex County, bordered on the east by Carlisle and Concord, on the west by B borough, on the north by Westford and Littleton, on the south by Sudbury, and on the southwest by Stow and' Maynard. Name: Acton as the name of our Town has several possible derivations: the old Saxon word Ac-tun meaning oak settlement or hamlet in the oaks, the Town of Acton, England, the Acton family of England, a member of which supposedly offered a bell for the first meeting house in 1735. Elevation at Town Hall: 268' above mean sea level. Land Area: Approximately 20 square miles. Population: Year Persons Density 1910 2136 106 per sq. 1950 3510 175 1955 4681 233 1960 7238 361 1965 10188 507 1970 14770 739 Climate: Normal January temperature 27.7° F. Normal July temperature 72.0° F. Normal annual precipitation 43.02 inches. Public Education: Pupil enrollment (October 1971): Grades 1-6, 2437; Grades 7-12, 2290 (Regional) Number of teachers and administrative staff: 291 Pupil-teacher ratio: 1 to 27 (avg. elementary grades) 1 to 20 (avg. Jr. and Sr. High) Tax Picture: Year Tax Rate Assessed Valuation 1966 $29 $70,309,795 1967 31 74,262,745 1968 34 79,513,915 1969 38.50 88,979,095 1970 43 97,088,304 1971 45 104,939,555 United States Senators in Congress: Edward W. Brooke (R), Newton, Massachusetts Edward M. -

![The Gift of Silence [Donner Les Bruits]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1746/the-gift-of-silence-donner-les-bruits-6651746.webp)

The Gift of Silence [Donner Les Bruits]

The Gift of Silence [donner les bruits] I'm wondering if silence itself is perhaps the mystery at the heart of music? And is silence the most perfect music of all? (Sting, in his speech on the occasion of his acceptance of an honorary doctorate from the Berklee College of Music on 15 May, 1994.) [1] What is music? This question investigates the borderline between music and what can no longer be considered music. It is the question of the frame of music since the frame is what distinguishes it as music, what 'produces' music. Without it, music is not music. It can be asked whether the frame is central or marginal, essential or supplemental. The frame itself is not music. Once the frame encloses the music and makes music music, it is external to the music. But as a frame of music, it also belongs to the music. Can we say that the frame is (n)either simply inside (n)or outside music? What is music? What is the frame of music? In order to answer these questions, music needs to be pushed to its boundaries. This then raises the question of what takes place on the borderline between music and non-music; it is a question of the most intimate and, at the same time, the other of music. It can be said that music is bordered by two distinct entities. On one hand, there are sounds that we no longer consider music: noise. On the other hand, there is the absence of sound: silence. (But exactly how different is this 'other' hand? An important question that will be elaborated upon extensively.) 'Music is inscribed between noise and silence', says Jacques Attali (Attali, p.19). -

Rod Serling Papers, 1945-1969

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt5489n8zx No online items Finding Aid for the Rod Serling papers, 1945-1969 Finding aid prepared by Processed by Simone Fujita in the Center for Primary Research and Training (CFPRT), with assistance from Kelley Wolfe Bachli, 2010. Prior processing by Manuscripts Division staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2002 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Rod Serling 1035 1 papers, 1945-1969 Descriptive Summary Title: Rod Serling papers Date (inclusive): 1945-1969 Collection number: 1035 Creator: Serling, Rod, 1924- Extent: 23 boxes (11.5 linear ft.) Abstract: Rodman Edward Serling (1924-1975) wrote teleplays, screenplays, and many of the scripts for The Twilight Zone (1959-65). He also won 6 Emmy awards. The collection consists of scripts for films and television, including scripts for Serling's television program, The Twilight Zone. Also includes correspondence and business records primarily from 1966-1968. Language: Finding aid is written in English. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Department of Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. -

Greek Tragedy on Radio

AN EAR FOR AN EYE: GREEK TRAGEDY ON RADIO by Natalie Anastasia Papoutsis A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Centre for Study of Drama University of Toronto © Copyright by Natalie Anastasia Papoutsis 2011 An Ear for an Eye: Greek Tragedy on Radio Natalie Anastasia Papoutsis Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Centre for Study of Drama University of Toronto 2011 Abstract An Ear for an Eye: Greek Tragedy on Radio examines the dramaturgical principles involved in the adaptation of Greek tragedies for production as radio dramas by considering the classical dramatic form’s representational ability through purely oral means and the effects of dramaturgical interventions. The inherent orality of these tragedies and Aristotle’s suggested limitation of spectacle ( opsis ) appears to make them eminently suitable for radio, a medium in which the visual dimension of plays is relegated entirely to the imagination through the agency of sound. Utilizing productions from Canadian and British national radio (where classical adaptations are both culturally mandated and technically practical) from the height of radio’s golden age to the present, this study demonstrates how producers adapted to the unique formal properties of radio. The appendices include annotated, chronological lists of 154 CBC and BBC productions that were identified in the course of research, providing a significant resource for future investigators. ii The dissertation first examines the proximate forces which shaped radio dramaturgy and radio listeners. Situating the emergence of radio in the context of modernity, Chapter One elucidates how audiences responded to radio’s return to orality within a visually-oriented culture.