Passive Solar Greenhouse in Ladakh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final BLO,2012-13

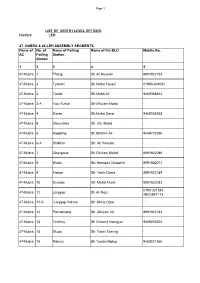

Page 1 LIST OF BOOTH LEVEL OFFICER . District: LEH 47- NUBRA & 48-LEH ASSEMBLY SEGMENTS. Name of No. of Name of Polling Name of the BLO Mobile.No. AC Polling Station Station 1 3 3 4 5 47-Nubra 1 Thang Sh.Ali Hussain 8991922153 47-Nubra 2 Tyakshi Sh.Mohd Yousuf 01980-248031 47-Nubra 3 Turtuk Sh.Mohd Ali 9469368812 47-Nubra 3-A Youl Turtuk Sh:Ghulam Mohd - 47-Nubra 4 Garari Sh.Mohd Omar 9469265938 47-Nubra 5 Chulunkha Sh: Gh. Mohd - 47-Nubra 6 Bogdang Sh.Ibrahim Ali 9469732596 47-Nubra 6-A Shilkhor Sh: Ali Hassain - 47-Nubra 7 Changmar Sh.Ghulam Mehdi 8991922086 47-Nubra 8 Waris Sh: Namgail Chosphel 8991922073 47-Nubra 9 Fastan Sh: Tashi Dawa 8991922149 47-Nubra 10 Sunudo Sh: Mohd Anvar 8991922082 0190-221344 47-Nubra 11 Largyap Sh Ali Rozi /9622957173 47-Nubra 11-A Largyap Yokma Sh: Nima Otzer - 47-Nubra 12 Pachathang Sh. Ghulam Ali 8991922182 47-Nubra 13 Terchey Sh Chemet Namgyal 9469266204 47-Nubra 14 Skuru Sh; Tashi Tsering - 47-Nubra 15 Rakuru Sh Tsetan Motup 9469221366 Page 2 47-Nubra 16 Udamaru Sh:Mohd Ali 8991922151 47-Nubra 16-A Shukur Sh: Sonam Tashi - 47-Nubra 17 Hunderi Sh: Tashi Nurbu 8991922110 47-Nubra 18 Hunder Sh Ghulam Hussain 9469177470 47-Nubra 19 Hundar Dok Sh Phunchok Angchok 9469221358 47-Nubra 20 Skampuk Sh: Lobzang Thokmed - 47-Nubra 21 Partapur Smt. Sari Bano - 47-Nubra 22 Diskit Sh: Tsering Stobdan 01980-220011 47-Nubra 23 Burma Sh Tuskor Tagais 8991922100 47-Nubra 24 Charasa Sh Tsewang Stobgais 9469190201 47-Nubra 25 Kuri Sh: Padma Gurmat 9419885156 47-Nubra 26 Murgi Thukje Zangpo 9419851148 47-Nubra 27 Tongsted -

1) Consider the Following Statements with Respect to Shram Shakti Portal

Daily Current Affairs Prelims Quiz - 22-01-2021 - (Online Prelims Test) 1) Consider the following statements with respect to Shram Shakti Portal 1. It is a National Migration Support Portal to help migrant workers. 2. It was launched by the Ministry of Tribal Affairs. Which of the statement(s) given above is/are correct? a. 1 only b. 2 only c. Both 1 and 2 d. Neither 1 nor 2 Answer : c In a move that would effectively help in the smooth formulation of State and National level programs for migrant workers, the Union Ministry of Tribal Affairs (MoTA) is launching Shram Shakti and Shram Saathi. ShramShakti – It is a National Migration Support Portal. Shram Saathi – It is a training manual for migrant workers at Goa. To facilitate and support approximately 4 lakhs migrants who come from different States to Goa, Chief Minister of Goa will also launch dedicated Migration cell in Goa. MoTA has also sanctioned Tribal research Institute, Tribal Museum, Van Dhan Kendras and Tribal Lok Utsav in Goa. 2) Consider the following statements with respect to India Science 1. It is an Internet-based science Over-The-Top (OTT) TV channel initiated by the Department of Science and Technology. 2. It has been implemented and managed by Prasar Bharati, an autonomous organization of the Department of Information and Broadcasting. Which of the statement(s) given above is/are correct? a. 1 only b. 2 only c. Both 1 and 2 d. Neither 1 nor 2 Answer : a India Science, Nation’s Science & Technology OTT (Over-the-top) channel has completed its second year of existence. -

A Pilot Survey of the Avifauna of Rangdum Valley, Kargil, Ladakh (Indian Trans-Himalaya)

Journal of Threatened Taxa | www.threatenedtaxa.org | 26 May 2015 | 7(6): 7274–7281 A pilot survey of the avifauna of Rangdum Valley, Kargil, Ladakh (Indian Trans-Himalaya) ISSN 0974-7907 (Online) 1 2 3 Short Communication Short Tanveer Ahmed , Afifullah Khan & Pankaj Chandan ISSN 0974-7893 (Print) 1,2 Aligarh Muslim University, Department of Wildlife Sciences, Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh 202002, India OPEN ACCESS 3 WWF-India, 172-B, Lodhi Estate, New Delhi 110003, India 1 [email protected] (corresponding author), 2 [email protected],3 [email protected] Abstract: An avifaunal survey of Rangdum Valley in Kargil District, Pradesh) and Ladakh (Jammu & Kashmir) at an average Jammu & Kashmir, India was carried out between June and July 2011. altitude of over 4000m. In Ladakh, studies on avifauna McKinnon’s species richness and total count methods were used. A total of 69 species were recorded comprising six passage migrants, were initiated by A.L. Adam as early as 1859 (Adam 25 residents, 36 summer visitors and three vagrants. The recorded 1859). Some avifaunal surveys in this region were species represents seven orders and 24 families, accounting for 23% th of the species known from Ladakh. A majority of the bird species are carried out in early 20 century (Ludlow 1920; Wathen insectivores. 1923; Osmaston 1925, 1927). Later, more studies on avian species in different parts of Ladakh were Keywords: Avifauna, feeding guild, Ladakh, Rangdum Valley, status. carried out by Holmes (1986), Mallon (1987), Mishra & Humbert-Droz (1998), Singh & Jayapal (2000), Pfister The Himalaya constitute one of the richest and (2001), Namgail (2005), Sangha & Naoroji (2005a,b), most unique ecosystems on the earth. -

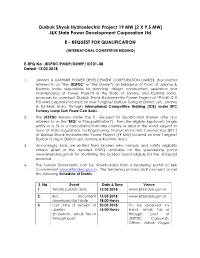

Durbuk Shyok Hydroelectric Project 19 MW (2 X 9.5 MW) J&K State Power Development Corporation Ltd

Durbuk Shyok Hydroelectric Project 19 MW (2 X 9.5 MW) J&K State Power Development Corporation Ltd. E - REQUEST FOR QUALIFICATION (INTERNATIONAL COMPETITIVE BIDDING) E-RFQ No: JKSPDC/PMDP/DSHEP/10101-08 Dated: 13.03.2018 1. JAMMU & KASHMIR POWER DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION LIMITED, (hereinafter referred to as “the JKSPDC" or "the Owner”) an Enterprise of Govt. of Jammu & Kashmir, India, responsible for planning, design, construction, operation and maintenance of Power Projects in the State of Jammu and Kashmir, India, proposes to construct Durbuk Shyok Hydroelectric Power Project of 19 MW (2 X 9.5 MW) capacity located on river Tangtse/ Durbuk Gong in District Leh, Jammu & Kashmir, India, through International Competitive Bidding (ICB) under EPC Turnkey Lump Sum Fixed Cost Basis. 2. The JKSPDC hereby invites the E - Request for Qualification (herein after also referred to as the "RFQ" or "Prequalification") from the eligible Applicants (single entity or a JV or a consortium) from any country or area in the world subject to Govt of India regulations, for Engineering, Procurement and Construction (EPC) of Durbuk Shyok Hydroelectric Power Project (19 MW) located on river Tangtse/ Durbuk Gong in District Leh, Jammu & Kashmir, India. 3. Accordingly, bids are invited from bidders who comply and satisfy eligibility criteria given in the detailed E-RFQ available on the e-tendering portal www.jktenders.gov.in for shortlisting the bidders found eligible for the aforesaid proposal. 4. The Tender Documents can be downloaded from e-tendering portal of J&K Government www.jktenders.gov.in . The tendering process shall proceed as per the following Schedule of Events: S. -

Photographic Archives in Paris and London Pascale Dollfus

Photographic archives in Paris and London Pascale Dollfus To cite this version: Pascale Dollfus. Photographic archives in Paris and London. European bulletin of Himalayan research, University of Cambridge ; Südasien-Institut (Heidelberg, Allemagne)., 1999, Special double issue on photography dedicated to Corneille Jest, pp.103-106. hal-00586763 HAL Id: hal-00586763 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00586763 Submitted on 10 Feb 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. EBHR 15- 16. 1998- 1999 PHOTOGRAPHIC ARCHIVES IN PARIS AND epal among the Limbu. Rai. Chetri. Sherpa, Bhotiya and Sunuwar. LONDO ' Both these collections encompa'\s pictures of land flY PA CALE DOLL FUSS scapes. architecture. techniques. agriculture. herding, lrade, feslivals. shaman practices. rites or passage. etc. In addition to these major collecti ons. once can find I. PUOTOGRAPfIIC ARCIUVES IN PARIS 350 photographs taken in 1965 by Jaeques Millot. (director of the RCP epal) in the Kathmandu Valley. Photographic Library ("Phototheque"), Musee de approx. 110 photographs (c. 1966-67) by Mireille Helf /'lIommc. fer. related primari Iy to musicians caSles, 45 photo 1'1. du Trocadero. Paris 750 16. graphs (1967-68) by Marc Gaborieau. -

OU1901 092-099 Feature Cycling Ladakh

Cycling Ladakh Catching breath on the road to Rangdum monastery PICTURE CREDIT: Stanzin Jigmet/Pixel Challenger Breaking the There's much more to Kate Leeming's pre- Antarctic expeditions than preparation. Her journey in the Indian Himalaya was equally about changing peoples' lives. WORDS Kate Leeming 92 93 Cycling Ladakh A spectacular stream that eventually flows into the Suru River, on the 4,000m plains near Rangdum nergy was draining from my legs. My heart pounded hard and fast, trying to replenish my oxygen deficit. I gulped as much of the rarified air as I could, without great success; at 4,100m, the atmospheric oxygen is at just 11.5 per cent, compared to 20.9 per cent at sea level. As I continued to ascend towards the snow-capped peaks around Sirsir La pass, the temperature plummeted and my body, drenched in a lather of perspiration, Estarted to get cold, further sapping my energy stores. Sirsir La, at 4,828m, is a few metres higher than Europe’s Mont Blanc, and I was just over half way up the continuous 1,670m ascent to get there. This physiological response may have been a reality check, but it was no surprise. The ride to the remote village of Photoksar on the third day of my altitude cycling expedition in the Indian Himalaya had always loomed as an enormous challenge, and I was not yet fully acclimatised. I drew on experience to pace myself: keeping the pedals spinning in a low gear, trying to relax as much as possible and avoiding unnecessary exertion. -

Statistical Handbook District Kargil 2018-19

Statistical Handbook District Kargil 2018-19 “STATISTICAL HANDBOOK” DISTRICT KARGIL UNION TERRITORY OF LADAKH FOR THE YEAR 2018-19 RELEASED BY: DISTRICT STATISTICAL & EVALUATION OFFICE KARGIL D.C OFFICE COMPLEX BAROO KARGIL J&K. TELE/FAX: 01985-233973 E-MAIL: [email protected] Statistical Handbook District Kargil 2018-19 THE ADMINISTRATION OF UNION TERRITORY OF LADAKH, Chairman/ Chief Executive Councilor, LAHDC Kargil Phone No: 01985 233827, 233856 Message It gives me immense pleasure to know that District Statistics & Evaluation Agency Kargil is coming up with the latest issue of its ideal publication “Statistical Handbook 2018-19”. The publication is of paramount importance as it contains valuable statistical profile of different sectors of the district. I hope this Hand book will be useful to Administrators, Research Scholars, Statisticians and Socio-Economic planners who are in need of different statistics relating to Kargil District. I appreciate the efforts put in by the District Statistics & Evaluation Officer and the associated team of officers and officials in bringing out this excellent broad based publication which is getting a claim from different quarters and user agencies. Sd/= (Feroz Ahmed Khan ) Chairman/Chief Executive Councilor LAHDC, Kargil Statistical Handbook District Kargil 2018-19 THE ADMINISTRATION OF UNION TERRITORY OF LADAKH District Magistrate, (Deputy Commissioner/CEO) LAHDC Kargil Phone No: 01985-232216, Tele Fax: 232644 Message I am glad to know that the district Statistics and Evaluation Office Kargil is releasing its latest annual publication “Statistical Handbook” for the year 2018- 19. The present publication contains statistics related to infrastructure as well as Socio Economic development of Kargil District. -

Field Guide Mammals of Ladakh ¾-Hðgå-ÅÛ-Hýh-ºiô-;Ým-Mû-Ç+Ô¼-¾-Zçàz-Çeômü

Field Guide Mammals of Ladakh ¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-hÝh-ºIô-;Ým-mÛ-Ç+ô¼-¾-zÇÀz-Çeômü Tahir Shawl Jigmet Takpa Phuntsog Tashi Yamini Panchaksharam 2 FOREWORD Ladakh is one of the most wonderful places on earth with unique biodiversity. I have the privilege of forwarding the fi eld guide on mammals of Ladakh which is part of a series of bilingual (English and Ladakhi) fi eld guides developed by WWF-India. It is not just because of my involvement in the conservation issues of the state of Jammu & Kashmir, but I am impressed with the Ladakhi version of the Field Guide. As the Field Guide has been specially produced for the local youth, I hope that the Guide will help in conserving the unique mammal species of Ladakh. I also hope that the Guide will become a companion for every nature lover visiting Ladakh. I commend the efforts of the authors in bringing out this unique publication. A K Srivastava, IFS Chief Wildlife Warden, Govt. of Jammu & Kashmir 3 ÇSôm-zXôhü ¾-hÐGÅ-mÛ-ºWÛG-dïm-mP-¾-ÆôG-VGÅ-Ço-±ôGÅ-»ôh-źÛ-GmÅ-Å-h¤ÛGÅ-zž-ŸÛG-»Ûm-môGü ¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-Å-GmÅ-;Ým-¾-»ôh-qºÛ-Åï¤Å-Tm-±P-¤ºÛ-MãÅ-‚Å-q-ºhÛ-¾-ÇSôm-zXôh-‚ô-‚Å- qôºÛ-PºÛ-¾Å-ºGm-»Ûm-môGü ºÛ-zô-P-¼P-W¤-¤Þ-;-ÁÛ-¤Û¼-¼Û-¼P-zŸÛm-D¤-ÆâP-Bôz-hP- ºƒï¾-»ôh-¤Dm-qôÅ-‚Å-¼ï-¤m-q-ºÛ-zô-¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-Ç+h-hï-mP-P-»ôh-‚Å-qôº-È-¾Å-bï-»P- zÁh- »ôPÅü Åï¤Å-Tm-±P-¤ºÛ-MãÅ-‚ô-‚Å-qô-h¤ÛGÅ-zž-¾ÛÅ-GŸôm-mÝ-;Ým-¾-wm-‚Å-¾-ºwÛP-yï-»Ûm- môG ºô-zôºÛ-;-mÅ-¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-h¤ÛGÅ-zž-Tm-mÛ-Åï¤Å-Tm-ÆâP-BôzÅ-¾-wm-qºÛ-¼Û-zô-»Ûm- hôm-m-®ôGÅ-¾ü ¼P-zŸÛm-D¤Å-¾-ºfh-qô-»ôh-¤Dm-±P-¤-¾ºP-wm-fôGÅ-qºÛ-¼ï-z-»Ûmü ºhÛ-®ßGÅ-ºô-zM¾-¤²h-hï-ºƒÛ-¤Dm-mÛ-ºhÛ-hqï-V-zô-q¼-¾-zMz-Çeï-Çtï¾-hGôÅ-»Ûm-môG Íï-;ï-ÁÙÛ-¶Å-b-z-ͺÛ-Íïw-ÍôÅ- mGÅ-±ôGÅ-Åï¤Å-Tm-ÆâP-Bôz-Çkï-DG-GÛ-hqôm-qô-G®ô-zô-W¤- ¤Þ-;ÁÛ-¤Û¼-GŸÝP.ü 4 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The fi eld guide is the result of exhaustive work by a large number of people. -

Changing Land Use and Water Management in a Ladakhi Village of Northern India

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Agriculture and Agricultural Science Procedia 5 ( 2015 ) 60 – 66 1st International Conference on Asian Highland Natural Resources Management, AsiaHiLand 2015 Changing Land Use and Water Management in a Ladakhi Village of Northern India aӒ b Shinya Takeda , Takayoshi Yamaguchi aGraduate School of Asian and African Area Studies, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan bThe National Institute for Agro-Environmental Sciences, Tsukuba 305-8604, Japan ABSTRACT Focusing on agro-pastoralism and the change in farmland use by the highlanders in Ladakh, Domkhar valley in lower Ladakh was selected as the research site. Domkhar valley has a total population of 1,269 people and 193 households and is divided into three villages based on their locations: Domkhar Do (lower village, 3,000 to 3,100 meters altitude), Domkhar Barma (middle village, 3,400 to 3,500 meters altitude), and Domkhar Gonma (upper village, 3,600 to 4,000 meters altitude). There is a hamlet called Kuramric at the highest point of the upper village at 4,100 meters. The villagers release their livestock in the pastures in the U- shaped valley located above Kuramric. Barley is the main crop cultivated in all three villages. Wheat can be cultivated in the lower and middle villages, but not in the upper village. We created a list of households in the three villages in Domkhar valley before conducting interviews. We then created a map showing irrigation canals, the land ownership and usage of each household from the GeoEye-1 satellite images taken in September and November 2010. We elucidated the change in land use and water management based on this map of irrigation canals, land ownership and usage along with the interviews and on-site observations. -

INDIA102 Full Appeal Final Version

SECRETARIAT - 150 route de Ferney, P.O. Box 2100, 1211 Geneva 2, Switzerland - TEL: +41 22 791 6033 - FAX: +41 22 791 6506 www .actalliance.org Appeal India Relief Assistance to People Affected by Flash Floods and Landslides in Ladakh - IND102 Appeal Target: US$ 1,131,182 Balance Requested: US$ 1,067,607 Geneva, 17 September 2010 Dear Colleagues, The town of Leh in Ladakh, in northeastern Jammu & Kashmir state, experienced deadly flash floods caused by a cloudburst lasting several hours on 6 August 2010. This in turn triggered raging floods and landslides. Hundreds of homes were destroyed and people marooned. More than 200 mud-built houses were washed away. The district hospital is submerged and the radio station damaged. Electricity cables and telecommunication pylons have been damaged or destroyed. The affected area stretches from the village of Phayang on the Rohtang-Leh highway to Nimoo on the Leh- Srinagar highway (a distance of more than 150 km). Five villages were severely affected in the sudden downpour and flash floods, including Choglumsar and Shapoo. Leh town was among the worst-hit areas. Leh has a population of 117,000, most of whom are taking shelter in the higher mountains around them. Over 200 people are still reported to be missing from the worst-hit village of Choglumsar, 13km from Leh city, where nearly all homes were washed away. Phayang, 15km from Leh, was also badly hit and is completely submerged. ACT Alliance members Church’s Auxiliary for Social Action (CASA) and the Lutheran World Federation/Lutheran World Service India Trust (LWF/LWSIT) are responding to this emergency. -

Tectono-Thermal Evolution of the India-Asia Collision Zone Based on 40Ar-39Ar Thermochronology in Ladakh, India

Tectono-thermal evolution of the India-Asia collision zone based on 40Ar-39Ar thermochronology in Ladakh, India Rajneesh Bhutani1∗, Kanchan Pande2 and T R Venkatesan3 1Department of Earth Sciences, Pondicherry University, Pondicherry 605 014, India. 2Department of Earth Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology, Powai, Mumbai 400 076, India. 3A2, Anand flats, 40, 2nd main road, Gandhinagar, Adyar, Chennai 600 020, India. ∗e-mail: [email protected] New 40Ar-39Ar thermochronological results from the Ladakh region in the India-Asia collision zone provide a tectono-thermal evolutionary scenario. The characteristic granodiorite of the Ladakh batholith near Leh yielded a plateau age of 46.3 ± 0.6Ma(2σ). Biotite from the same rock yielded a plateau age of 44.6 ± 0.3Ma(2σ). The youngest phase of the Ladakh batholith, the leucogranite near Himya, yielded a cooling pattern with a plateau-like age of ∼ 36 Ma. The plateau age of muscovite from the same rock is 29.8 ± 0.2Ma (2σ). These ages indicate post-collision tectono- thermal activity, which may have been responsible for partial melting within the Ladakh batholith. Two basalt samples from Sumdo Nala have also recorded the post-collision tectono-thermal event, which lasted at least for 8 MY in the suture zone since the collision, whereas in the western part of the Indus Suture, pillow lava of Chiktan showed no effect of this event and yielded an age of emplacement of 128.2 ± 2.6Ma (2σ). The available data indicate that post-collision deformation led to the crustal thickening causing an increase in temperature, which may have caused partial melting at the base of the thickened crust. -

Economic Review” of District Leh, for the Year 2014-15

PREFACE The District Statistics and Evaluation Agency Leh under the patronage of Directorate of Economic and Statistics (Planning and Development Department) is bringing out annual publication titled “Economic Review” of District Leh, for the year 2014-15. The publication 22st in the series, presents the progress achieved in various socio-economic facts of the district economy. I hope that the publication will be a useful tool in the hands of planners, administrators, Policy makers, academicians and other users and will go a long way in helping them in their respective pursuit. Suggestions to improve the publication in terms of coverage, quality etc. in the future issue of the publication will be appreciated Tashi Tundup District statistics and Evaluation Officer Leh CONTENTS Page No. District Profile 1-6 Agriculture and Allied Activities • Agriculture 7-9 • Horticulture 10 • Animal Husbandry 11-13 • Sheep Husbandry 14-15 • Forest 16 • Soil Conservation 17 • Cooperative 17-18 • Irrigation 19 Industries and Employment • Industries 19-20 • Employment & Counseling Centre 20 • Handicraft/Handloom 21 Economic Infrastructure • Power 21-22 • Tourism 22-23 • Financial institution 24-25 • Transport and communication 24-27 • Information Technology 27-28 Social Sector • Housing 29 • Education 29-31 • Health 31-33 • Water Supply and Rural Sanitation 33 • Women and Child Development 34-36 1 DISTRICT PROFILE . Although, Leh district is one of the largest districts of the country in terms of area, it has the lowest population density across the entire country. The district borders Pakistan occupied Kashmir and Chinese occupied Ladakh in the North and Northwest respectively, Tibet in the east and Lahoul-Spiti area of Himachal Pradesh in the South.