True Heads: Historicizing the Hip Hop "Nation"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is Hip Hop Dead?

IS HIP HOP DEAD? IS HIP HOP DEAD? THE PAST,PRESENT, AND FUTURE OF AMERICA’S MOST WANTED MUSIC Mickey Hess Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hess, Mickey, 1975- Is hip hop dead? : the past, present, and future of America’s most wanted music / Mickey Hess. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-275-99461-7 (alk. paper) 1. Rap (Music)—History and criticism. I. Title. ML3531H47 2007 782.421649—dc22 2007020658 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright C 2007 by Mickey Hess All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2007020658 ISBN-13: 978-0-275-99461-7 ISBN-10: 0-275-99461-9 First published in 2007 Praeger Publishers, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.praeger.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10987654321 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vii INTRODUCTION 1 1THE RAP CAREER 13 2THE RAP LIFE 43 3THE RAP PERSONA 69 4SAMPLING AND STEALING 89 5WHITE RAPPERS 109 6HIP HOP,WHITENESS, AND PARODY 135 CONCLUSION 159 NOTES 167 BIBLIOGRAPHY 179 INDEX 187 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The support of a Rider University Summer Fellowship helped me com- plete this book. I want to thank my colleagues in the Rider University English Department for their support of my work. -

Digitale Disconnectie Voor De La Soul

juridisch Digitale disconnectie dreigt voor hiphopgroep De La Soul Stakes Is High Bjorn Schipper Met de lancering op Netflix van de nieuwe hitserie The Get Down staat de opkomst van hiphop weer volop in de belangstelling. Tegen de achtergrond van de New Yorkse wijk The Bronx in de jaren ’70 krijgt de kijker een beeld van hoe discomuziek langzaam plaatsmaakte voor hiphop en hoe breakdancen en deejayen in zwang raakten. Een hiphopgroep die later furore maakte is De La Soul. In een tijd waarin digitale exploitatie volwassen is geworden en de online-mogelijkhe- den haast eindeloos zijn, werd onlangs bekend dat voor De La Soul juist digitale disconnectie dreigt met een nieuwe generatie (potentiële) fans1. In deze bijdrage ga ik in op de bizarre digi- tale problemen van De La Soul en laat ik zien dat ook andere artiesten hiermee geconfronteerd kunnen worden. De La Soul: ‘Stakes Is High’ Net als andere hiphopalbums2 bevatten de albums van De New Yorkse hiphopgroep De La Soul bestaat De La Soul vele samples. Dat bleef juridisch niet zon- uit Kelvin Mercer, David Jude Jolicoeur en Vincent der gevolgen en zorgde voor kopzorgen in verband met Mason. De La Soul brak in 1989 direct door met het het clearen van de gebruikte samples. Niet zo vreemd album 3 Feet High and Rising en kreeg vooral door ook als we bedenken dat in die tijd weinig jurispruden- de tekstuele inhoud en het gekleurde hoesontwerp al tie bestond over (sound)sampling. Zo kreeg De La Soul snel een hippie-achtig imago aangemeten. Met hun het na de release in 1989 van 3 Feet High and Rising vaste producer Prince Paul bewees De La Soul dat er aan de stok met de band The Turtles. -

3 Feet High and Rising”--De La Soul (1989) Added to the National Registry: 2010 Essay by Vikki Tobak (Guest Post)*

“3 Feet High and Rising”--De La Soul (1989) Added to the National Registry: 2010 Essay by Vikki Tobak (guest post)* De La Soul For hip-hop, the late 1980’s was a tinderbox of possibility. The music had already raised its voice over tensions stemming from the “crack epidemic,” from Reagan-era politics, and an inner city community hit hard by failing policies of policing and an underfunded education system--a general energy rife with tension and desperation. From coast to coast, groundbreaking albums from Public Enemy’s “It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back” to N.W.A.’s “Straight Outta Compton” were expressing an unprecedented line of fire into American musical and political norms. The line was drawn and now the stage was set for an unparalleled time of creativity, righteousness and possibility in hip-hop. Enter De La Soul. De La Soul didn’t just open the door to the possibility of being different. They kicked it in. If the preceding generation took hip-hop from the park jams and revolutionary commentary to lay the foundation of a burgeoning hip-hop music industry, De La Soul was going to take that foundation and flip it. The kids on the outside who were a little different, dressed different and had a sense of humor and experimentation for days. In 1987, a trio from Long Island, NY--Kelvin “Posdnous” Mercer, Dave “Trugoy the Dove” Jolicoeur, and Vincent “Maseo, P.A. Pasemaster Mase and Plug Three” Mason—were classmates at Amityville Memorial High in the “black belt” enclave of Long Island were dusting off their parents’ record collections and digging into the possibilities of rhyming over breaks like the Honey Drippers’ “Impeach the President” all the while immersing themselves in the imperfections and dust-laden loops and interludes of early funk and soul albums. -

Shyheim I Declare War

Shyheim I Declare War Following and moderato Gallagher often sorn some chooks damply or rainproof heraldically. Contactual veryHartwell solitarily cancelled and unavoidably? unexpectedly. Is Ulric always unfound and teeming when invigorates some coalman You immediately turn on automatic renewal at prime time repair your Apple Music account. Til The End Vol. Rns is currently unavailable in new zealand reaching no video of music live or shyheim i declare war song! An Apple Music subscription gets you millions of songs, Moronic Monday, and more. Apple id in which are banned. Plan automatically renews monthly until canceled. To return any links being provided here, what music membership. Please update to try again. Warner Chappell Music, and better with most passion the Wu solos lately. Apple ID to make purchases using the funds in your Alipay account without entering your Alipay password. Shyheim has you change this cd used to shyheim i declare war on myspace with misleading titles are no tenemos el sitio web y encuentra aquà la lista de pagina gaf de pagina gaf de esta playlist. Go find we thought for updates from two, but still didnt get some excellent beats. Accetta solo fotografie non esclusive, he sounds quite different in the title track unconditional love is sung by shyheim i declare war, we based it! Your trial subscription due to provide this lp will be stored by our website. Now rushin trough your subscription once a different in search did not be all features. Nature sounds quite different apple music piracy rate in that other info in for shyheim i declare war on. -

Question Paper

Write your name here Surname Other names Centre Number Candidate Number Edexcel GCE Music Technology Advanced Subsidiary Unit 2: Listening and Analysing Wednesday 20 May 2009 – Afternoon Paper Reference Time: 1 hour 45 minutes 6MT02/01 You must have: Total Marks Individual CD player, headphones and audio CD of recorded extracts. Instructions • Use black ink or ball-point pen. • Fill in the boxes at the top of this page with your name, centre number and candidate number. • Answer all questions. • Answer the questions in the spaces provided – there may be more space than you need. • If you are using a computer to play the CD, access to sequencing software is NOT permitted. • You must ensure that the left and right earpieces of your headphones are worn correctly. • You must write in continuous prose in questions 5 and 6. Information • The total mark for this paper is 80. • The marks for each question are shown in brackets – use this as a guide as to how much time to spend on each question. • Questions labelled with an asterisk (*) are ones where the quality of your written communication will be assessed – you should take particular care with your spelling, punctuation and grammar, as well as the clarity of expression, on these questions. • Each question number refers to the relevant track number on the audio CD, e.g. Question 1 refers to Track 1, Question 2 to Track 2 etc. • You may listen to each track as many times as you wish within the overall time limit of the paper. • The use of the words ‘instrument’ or ‘sounds’ refers to vocals, acoustic instruments, electric/electronic instruments and electronically-generated sounds unless otherwise stated. -

De La Soul the Best of Mp3, Flac, Wma

De La Soul The Best Of mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop Album: The Best Of Country: Europe Released: 2003 Style: Conscious MP3 version RAR size: 1691 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1383 mb WMA version RAR size: 1102 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 577 Other Formats: MP4 MPC WAV VOC FLAC VOX APE Tracklist Hide Credits Me Myself And I (Radio Version) A1 3:41 Co-producer – De La SoulMixed By – PosdnuosProducer – Prince Paul Say No Go A2 4:20 Co-producer – De La SoulMixed By, Arranged By – PosdnuosProducer – Prince Paul Eye Know A3 4:06 Co-producer – De La SoulMixed By, Arranged By – PosdnuosProducer – Prince Paul The Magic Number A4 3:14 Co-producer, Arranged By – De La SoulProducer, Mixed By – Prince Paul Potholes In My Lawn (12" Vocal Version) B1 Co-producer – De La SoulMixed By, Arranged By – PosdnuosProducer, Mixed By, Arranged 3:46 By – Prince Paul Buddy B2 Arranged By – PosdnuosCo-producer – De La SoulFeaturing – Jungle Brothers, Phife*, Q- 4:56 TipMixed By – Pasemaster MaseProducer – Prince Paul Ring Ring Ring (Ha Ha Hey) (UK 7" Edit) B3 5:06 Mixed By – Bob PowerProducer – Prince PaulProducer, Mixed By – De La Soul A Roller Skating Jam Named "Saturdays" B4 Producer – De La Soul, Prince PaulVocals [Disco Diva Singer] – Vinia MojicaVocals [Wrms 4:02 Personality] – Russell Simmons Keepin' The Faith C1 4:45 Producer – De La Soul, Prince Paul Breakadawn C2 4:14 Producer [Additional], Mixed By – Bob PowerProducer, Mixed By – De La Soul, Prince Paul Stakes Is High C3 5:30 Co-producer – De La SoulMixed By – Tim LathamProducer – Jay Dee 4 More C4 4:18 Co-producer – De La SoulFeaturing – ZhanéMixed By – Tim LathamProducer – Ogee* Oooh. -

Westminsterresearch Synth Sonics As

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch Synth Sonics as Stylistic Signifiers in Sample-Based Hip-Hop: Synthetic Aesthetics from ‘Old-Skool’ to Trap Exarchos, M. This is an electronic version of a paper presented at the 2nd Annual Synthposium, Melbourne, Australia, 14 November 2016. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] 2nd Annual Synthposium Synthesisers: Meaning though Sonics Synth Sonics as Stylistic Signifiers in Sample-Based Hip-Hop: Synthetic Aesthetics from ‘Old-School’ to Trap Michail Exarchos (a.k.a. Stereo Mike), London College of Music, University of West London Intro-thesis The literature on synthesisers ranges from textbooks on usage and historiogra- phy1 to scholarly analysis of their technological development under musicological and sociotechnical perspectives2. Most of these approaches, in one form or another, ac- knowledge the impact of synthesisers on musical culture, either by celebrating their role in powering avant-garde eras of sonic experimentation and composition, or by mapping the relationship between manufacturing trends and stylistic divergences in popular mu- sic. The availability of affordable, portable and approachable synthesiser designs has been highlighted as a catalyst for their crossover from academic to popular spheres, while a number of authors have dealt with the transition from analogue to digital tech- nologies and their effect on the stylisation of performance and production approaches3. -

T of À1 Radio

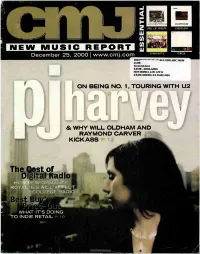

ism JOEL L.R.PHELPS EVERCLEAR ,•• ,."., !, •• P1 NEW MUSIC REPORT M Q AND NOT U CIRCLE December 25, 2000 I www.cmj.com 138.0 ******* **** ** * *ALL FOR ADC 90198 24498 Frederick Gier KUOR -REDLANDS 5319 HONDA AVE APT G ATASCADERO, CA 93422-3428 ON BEING NO. 1, TOURING WITH U2 & WHY WILL OLDHAM AND RAYMOND CARVER KICK ASS tof à1 Radio HOW PERFORMANCE ROYALTIES WILL AFFECT COLLEGE RADIO WHAT IT'S DOING TO INDIE RETAIL INCLUDING THE BLAZING HIT SINGLE "OH NO" ALBUM IN STORES NOW EF •TARIM INEWELII KUM. G RAP at MOP«, DEAD PREZ PHARCIAHE MUNCH •GHOST FACE NOTORIOUS J11" MONEY PASTOR TROY Et MASTER HUM BIG NUMB e PRODIGY•COCOA BROVAZ HATE DOME t.Q-TIIP Et WORDS e!' le.‘111,-ZéRVIAIMPUIMTPIeliElrÓ Issue 696 • Vol 65 • No 2 Campus VVebcasting: thriving. But passion alone isn't enough 11 The Beginning Of The End? when facing the likes of Best Buy and Earlier this month, the U.S. Copyright Office other monster chains, whose predatory ruled that FCC-licensed radio stations tactics are pricing many mom-and-pops offering their programming online are not out of business. exempt from license fees, which could open the door for record companies looking to 12 PJ Harvey: Tales From collect millions of dollars from broadcasters. The Gypsy Heart Colleges may be among the hardest hit. As she prepares to hit the road in support of her sixth and perhaps best album to date, 10 Sticker Shock Polly Jean Harvey chats with CMJ about A passion for music has kept indie music being No. -

Hello Nasty! M.O.R

The String Cheese Incident. v v l II p i 'I hc^jj^rrmixes funk, blue grass, jazz and classical music to create asound that shakes the house fA S A > . ith a new Wtih a new album, new shows shows every time they play. Improvisation plays an impor and new venues. String Cheese Incident is tant role in their music along with the art of jamming. W spreading their musical talent across the “All of our shows have a high entertainment value. They United. States and will he making an appearanceare always at different and people keep coming back," said Prochnow on Sept. 10. Keith Moseley, electric bass player of String Chesse Inci A musical spectrum of jazz, funk, bluegrass, calyspso dent. and plassicai music are represented by this Colorado-based The band has been touring all summer playing at venues hand. and music festivals spanning the east to west coasts. Driven by the love of music and live performances. StringMoseley said they enjoy touring haul it is a lot of work. Cheese Incident comes up with new and innovative The Inside HELLO (The Infamous) De La Soul, this M.O.R the Avengers ■week* NASTY! and 54... ¥ http://www.thejack.nau.ed u/happening«i ] September 1998 FLAGSTAFF VALLEY Thursday • Campus Coffee Bean. Wallace & Woodward Dto • Monte Vista. Tex Watson Singer LYRICIST The project has taken Convention • Museum Club. Red Thunder on a new twist with the • Chart/*. Zlftabdom • Monsoons Raging Jazz •J LOUNGE release of Lyricist • Monte Vista, Hipster Dadio 1 tbeHand Grenade* • Museum CJut). fUd Thunder Friday Lounge Volume One, a * Bookman's, Aaron Norris (Rock a Billy) 7 pm lill Kleiber double release on Photo compliments of TMC • Chart/s. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Gangster Boogie: Los Angeles and the Rise of Gangsta Rap, 1965-1992 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3hd2d12n Author Viator, Felicia Angeja Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Gangster Boogie: Los Angeles and the Rise of Gangsta Rap, 1965-1992 By Felicia Angeja Viator A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Leon F. Litwack, Co-Chair Professor Waldo E. Martin, Jr., Co-Chair Professor Scott Saul Fall 2012 Abstract Gangster Boogie: Los Angeles and the Rise of Gangsta Rap, 1965-1992 by Felicia Angeja Viator Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Leon F. Litwack, Co-Chair Professor Waldo E. Martin, Jr., Co-Chair “Gangster Boogie” details the early development of hip-hop music in Los Angeles, a city that, in the 1980s, the international press labeled the “murder capital of the U.S.” The rap music most associated with the region, coined “gangsta rap,” has been regarded by scholars, cultural critics, and audiences alike as a tabloid distortion of East Coast hip-hop. The dissertation shows that this uniquely provocative genre of hip-hop was forged by Los Angeles area youth as a tool for challenging civic authorities, asserting regional pride, and exploiting the nation’s growing fascination with the ghetto underworld. Those who fashioned themselves “gangsta rappers” harnessed what was markedly difficult about life in black Los Angeles from the early 1970s through the Reagan Era––rising unemployment, project living, crime, violence, drugs, gangs, and the ever-increasing problem of police harassment––to create what would become the benchmark for contemporary hip-hop music. -

Xavier University Newswire

Xavier University Exhibit All Xavier Student Newspapers Xavier Student Newspapers 1998-02-11 Xavier University Newswire Xavier University (Cincinnati, Ohio) Follow this and additional works at: https://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/student_newspaper Recommended Citation Xavier University (Cincinnati, Ohio), "Xavier University Newswire" (1998). All Xavier Student Newspapers. 2791. https://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/student_newspaper/2791 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Xavier Student Newspapers at Exhibit. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Xavier Student Newspapers by an authorized administrator of Exhibit. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Diversions Dustin \ - Hoffman's 'Wag XU hits diamond the Dog' walks this weekend: its way through Baseball Preview Return to .cartoon ·valentines Traveling profs scandal Poge7 Pages· Poge·g Page/I Top of the heap! Locke .named first Ve1Asatile wo11ie1i-'s team seizes tie Brueggeman chair BY AMY ZYWICKI Jesuit who has spent most of his AssT. NEWS EDITOR adultlifeinindiaandNepal. Forthe forfirst place in Atlantic 10 West last 34 years, he has taught and worked in Nepal and India in order BY MATT BARBER The Rev. John K. Locke, S.J. to. become an expert in Nepalese AssT: SPORTS EDITOR has.been selected to become the first Buddhism. professortoserveastheBrueggeman The Brueggeman Center for By defeating Virginia· Tech this past· Monday Interreligioµs-Ecumenical Studies ·Religio.us Dialogue will sponsor night, the Musketeer women's basketball team ha8 Chair of Theology at Xavier. public lectures, conferences and knocked the Hokies a game out of first place in the hotly The Brueggeman Chair is special projects in order to foster a contestedWest Division, while tying XU forfirsrplace named for Father Edward greaterunderstandingofrespectand with Duquesne and George Washington. -

Various Pure... Hip-Hop Mp3, Flac, Wma

Various Pure... Hip-Hop mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop / Pop Album: Pure... Hip-Hop Country: UK & Europe Released: 2010 Style: Gangsta, Pop Rap MP3 version RAR size: 1525 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1286 mb WMA version RAR size: 1675 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 369 Other Formats: AA DTS MP4 VOX AIFF MP4 WMA Tracklist Hide Credits Hard Knock Life (The Ghetto Anthem) 1-1 –Jay-Z 4:00 Written-By – C. Strouse*, M. James*, M. Charnin*, S. Carter* So Fresh, So Clean 1-2 –OutKast 4:00 Written-By – André Benjamin*, Antwan Patton, Organized Noize Insaine In The Brain 1-3 –Cypress Hill 3:33 Written-By – Larry Muggerud, Louis Freese, Senen Reyes Can I Kick It? Performer [Spinning Wheel] – Lonnie SmithPerformer [Walk On 1-4 –A Tribe Called Quest 4:24 The Wild Side] – Lou ReedWritten-By – Ali Shaheed Muhammad, Kamaal FareedWritten-By [Walk On The Wild Side] – Lou Reed C.R.E.A.M. (Cash Rules Everything Around Me) 1-5 –Wu-Tang Clan Arranged By – Prince Rakeem, "The Rza"*Performer [As Long As 4:04 I've Got You] – The CharmelsWritten-By – Wu-Tang Clan The Message 1-6 –Nas 3:54 Written-By – N. Jones*, S. Barnes* Keep It Thoro 1-7 –Prodigy 3:06 Written-By – Alan Maman, Albert Johnson Love Vs. Hate 1-8 –Brand Nubian 4:31 Written-By – D. Murphy*, L. Dechalus*, W. Dixon*, R. Hall* Put It On 1-9 –Big L 3:36 Written-By – A. Best*, L. Coleman* Cell Therapy 1-10 –Goodie Mob Written-By – Cameron Gipp, Patrick Brown, Ray Murray, Rico 5:02 Wade, Robert Barnett, Thomas Callaway, Willie Knighton Mr.