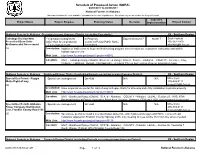

Determination of Effects for Federally Listed Species Are: 1) No Effect; 2) May Affect, but Not Likely to Adversely Affect; 3) May Affect, Likely to Adversely Affect

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Apalachicola & Conecuh National Forests

Apalachicola & Conecuh National Forests Recreation Realignment Report Prepared by: Christine Overdevest & H. Ken Cordell August, 2001 Web Series: SRS-4901-2001-4 Web Series: SRS-4901-2001-4 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................. 1 Report Objectives ............................................................ 1 On Analysis Assumptions ...................................................... 1 Vision of Interactive Session: How to Use this Report .................................. 2 Report Contents .............................................................. 3 The Realignment Context ....................................................... 4 Recreation Realignment Step 1. - Population Analysis ................................................... 6 Step 2. - Recreation Participation Analysis and Segmentation of Activities ................. 11 Step 3. - Analysis of Fastest Growing Outdoor Recreation Activities ..................... 16 Step 4. - Recreation Participation Analysis by Demographic Strata ....................... 17 Step 5. - Summing Step 4 Activity Scores Across Demographic Strata ................... 40 Step 6. - Summing Activity Scores Over 3 Dimensions of Demand ....................... 41 Step 7. - Identifying Niche Activities ............................................. 43 Step 8. - Equity Analysis ..................................................... 44 Step 9. - Other Suppliers of Outdoor Recreation in your Market Area ................... 47 Step 10 - Summary Observations, -

Land Areas of the National Forest System, As of September 30, 2019

United States Department of Agriculture Land Areas of the National Forest System As of September 30, 2019 Forest Service WO Lands FS-383 November 2019 Metric Equivalents When you know: Multiply by: To fnd: Inches (in) 2.54 Centimeters Feet (ft) 0.305 Meters Miles (mi) 1.609 Kilometers Acres (ac) 0.405 Hectares Square feet (ft2) 0.0929 Square meters Yards (yd) 0.914 Meters Square miles (mi2) 2.59 Square kilometers Pounds (lb) 0.454 Kilograms United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Land Areas of the WO, Lands National Forest FS-383 System November 2019 As of September 30, 2019 Published by: USDA Forest Service 1400 Independence Ave., SW Washington, DC 20250-0003 Website: https://www.fs.fed.us/land/staff/lar-index.shtml Cover Photo: Mt. Hood, Mt. Hood National Forest, Oregon Courtesy of: Susan Ruzicka USDA Forest Service WO Lands and Realty Management Statistics are current as of: 10/17/2019 The National Forest System (NFS) is comprised of: 154 National Forests 58 Purchase Units 20 National Grasslands 7 Land Utilization Projects 17 Research and Experimental Areas 28 Other Areas NFS lands are found in 43 States as well as Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. TOTAL NFS ACRES = 192,994,068 NFS lands are organized into: 9 Forest Service Regions 112 Administrative Forest or Forest-level units 503 Ranger District or District-level units The Forest Service administers 149 Wild and Scenic Rivers in 23 States and 456 National Wilderness Areas in 39 States. The Forest Service also administers several other types of nationally designated -

Introduction

00i-xvi_Mohl-East-00-FM 2/18/06 8:25 AM Page xv INTRODUCTION During the rapid development of the United States after the American Rev- olution, and during most of the 1900s, many forests in the United States were logged, with the logging often followed by devastating fires; ranchers converted the prairies and the plains into vast pastures for livestock; sheep were allowed to venture onto heretofore undisturbed alpine areas; and great amounts of land were turned over in an attempt to find gold, silver, and other minerals. In 1875, the American Forestry Association was born. This organization was asked by Secretary of the Interior Carl Schurz to try to change the con- cept that most people had about the wasting of our natural resources. One year later, the Division of Forestry was created within the Department of Agriculture. However, land fraud continued, with homesteaders asked by large lumber companies to buy land and then transfer the title of the land to the companies. In 1891, the American Forestry Association lobbied Con- gress to pass legislation that would allow forest reserves to be set aside and administered by the Department of the Interior, thus stopping wanton de- struction of forest lands. President Benjamin Harrison established forest re- serves totaling 13 million acres, the first being the Yellowstone Timberland Reserve, which later became the Shoshone and Teton national forests. Gifford Pinchot was the founder of scientific forestry in the United States, and President Theodore Roosevelt named him chief of the Forest Ser- vice in 1898 because of his wide-ranging policy on the conservation of nat- ural resources. -

Thematic Maps

Title Author/Publisher Date Scale Map Case Drawer Folder Notes Island of Puerto Rico Corps of Engineers, U.S. Army 1942 1:300,000 23 1 Puerto Rico - Misc Mapa de Puerto Rico American Map Corporation 1988 23 1 Puerto Rico - Misc United States Department of Puerto Rico E Islas Limitrofes The Interior Geological Survey 1971 1:120,000 23 1 Puerto Rico - Misc Protected Natural Areas of Puerto Rico US Department of Agriculture 2011 1:240,000 23 1 Puerto Rico - Misc Essential Geography of the United States of America Imus Cartographics 2010 1:4,000,000 23 1 United States - General Reference Maps G3700 2010 .I4 North American Environment Atlas: Mapping our shared British Oceanographic Data environment Centre 2003 1:10,000,000 23 1 United States - General Reference Maps United States American Map Corporation 1986 23 1 United States - General Reference Maps United States (Larger Map) American Map Corporation 1986 23 1 United States - General Reference Maps (No Clear Title) Map Of United States Esselte Map Service 1990 1:4,000,000 23 1 United States - General Reference Maps United States of America Imprime en Alleagne par 1986 1:15,000,000 23 1 United States - General Reference Maps United States 1990 1:15,000,000 23 1 United States - General Reference Maps United States of America Rand McNally and Company 1:4,000,000 23 1 United States - General Reference Maps United States : With Highways American Map Corporation 1992 23 1 United States - General Reference Maps United States USGS 1972 1:2,500,000 23 1 United States - General Reference Maps General -

Alabama's TREASURED Forests

Alabama’s TREASURED Forests A Publication of the Alabama Forestry Commission Summer 2011 Message from the STATE FORESTER n the heels of the devastation caused by the tornados this Governor Robert Bentley past April, a good portion of our state is in the process of Alabama Forestry Commission Orebuilding, restoring, even re-establishing Kenneth Real, Chairman roots in some cases. In this issue of Johnny McReynolds, Vice Chairman Alabama’s TREASURED Forests, we’re C. Irvin Eatman, Jr. highlighting recovery efforts and how the Randy Gilmore planting of trees can bring beauty, heal- Don Heath ing, and hope following such a horrific Melisa Love event. Jerry M. Smith It seems rather ironic that at this par- ticular time I should bring an issue to State Forester your attention that could result in signifi- Linda S. Casey cant increases in your reforestation costs. As State Forester and in keeping with the mission of the Alabama Forestry Commission, I need to make Assistant State Forester landowners, forestry service providers, forest industry, and other forest- Patrick Glass land stakeholders aware of certain upcoming U.S. Department of Labor rules that will impact the ability of landowners and others to cost-effec- Administrative Division Director tively reforest their property. Walter Cartwright The Department of Labor’s regulations change the methodology for calculating the prevailing wages paid H-2B “guest workers” and will Forest Operations Division Director result in reforestation cost increases of between 26 to 104 percent in Dan Jackson -

Appendix 1. Property Ids and Names (Sorted by Name)

Appendix 1. Property IDs and Names (sorted by name) Property Name Property ID State Alexander State Forest AXSF LA Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge ARNWR NC Angelina Ranger District, Angelina National Forest ANRDANF TX Apalachicola Ranger District, Apalachicola National Forest ARDANF FL Avalon Plantation AVPL FL Avon Park Air Force Range APAFR FL Bates Hill Plantation BHPL SC Bienville Ranger District, Bienville National Forest BRDBNF MS Big Branch Marsh National Wildlife Refuge BBMNWR LA Big Cypress National Preserve BCNP FL Black Bayou Lake NWR BBLNWR LA Blackwater River State Forest BRSF FL Bladen Lakes State Forest BLSF NC Blue Tract BT NC Brookgreen Gardens BG SC Brushy Creek Experimental Forest IPBCEF TX Bull Creek & Triple N Ranch Wildlife Management Areas BCWMA FL Burroughs & Chapin Company, Grand Dunes BCCGD SC Burroughs & Chapin Company, Horry County BCCHC SC Camp Blanding CB FL Camp Mackall CM NC Carolina Sandhills National Wildlife Refuge CSNWR SC Catahoula Ranger District, Kisatchie National Forest CRDKNF LA Cheraw State Fish Hatchery CSFH SC Cheraw State Park CSP SC Chickasawhay Ranger District, DeSoto National Forest CRDDNF MS Conecuh National Forest CNF AL Cooks Branch Conservancy CBC TX Croatan Ranger District, Croatan National Forest CRDCNF NC Crosett Experimental Forest CEF AR Cumberland County Private Lands CCPL NC D'Arbonne National Wildlife Refuge DNWR LA Dare County Bombing Range DCBR NC Davy Crockett National Forest DCNF TX Desoto Ranger District, Desoto National Forest DRDDNF MS Dupuis Wildllife and Environmental Area DWEA FL Eglin Air Force Base EAFB FL Enon and Sehoy Plantation ESPL AL Escape Ranch ERANCH FL Evangeline Unit, Calcasieu RD, Kisatchie National Forest EUCRDKNF LA Fairchild State Forest FSF TX Felsenthal National Wildlife Refuge FNWR AR Fort Benning FTBN GA Fort Bragg FTBG NC Fort Gordon FTGD GA Fort Jackson FTJK SC Fort Polk FTPK LA Fort Stewart FTST GA Francis Marion National Forest FMNF SC Fred C. -

At-Risk Species Assessment on Southern National Forests, Refuges, and Other Protected Areas

David Moynahan | St. Marks NWR At-Risk Species Assessment on Southern National Forests, Refuges, and Other Protected Areas National Wildlife Refuge Association Mark Sowers, Editor October 2017 1001 Connecticut Avenue NW, Suite 905, Washington, DC 20036 • 202-417-3803 • www.refugeassociation.org At-Risk Species Assessment on Southern National Forests, Refuges, and Other Protected Areas Table of Contents Introduction and Methods ................................................................................................3 Results and Discussion ......................................................................................................9 Suites of Species: Occurrences and Habitat Management ...........................................12 Progress and Next Steps .................................................................................................13 Appendix I: Suites of Species ..........................................................................................17 Florida Panhandle ............................................................................................................................18 Peninsular Florida .............................................................................................................................28 Southern Blue Ridge and Southern Ridge and Valley ...............................................................................................................................39 Interior Low Plateau and Cumberland Plateau, Central Ridge and Valley ...............................................................................................46 -

Environmental Assessment for Tuskegee Upland Pine Restoration

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Southern Region Environmental Assessment March for Tuskegee Upland Pine 2014 Restoration Tuskegee National Forest: Macon County For Project Information Contact: Eugene Brooks, Team Leader 2946 Chestnut Street Montgomery, AL 36107 334-241-8149 Tuskegee Upland Pine Restoration Project Table of Contents Chapter 1 – Purpose and Need .........................................................................................................1 Background .............................................................................................................................................. 1 Purpose and Need for Action .................................................................................................................. 5 Project Area Description .......................................................................................................................... 7 Proposed Action ....................................................................................................................................... 7 Decision Framework .............................................................................................................................. 11 Public Involvement ................................................................................................................................. 11 Chapter 2 – Alternatives .................................................................................................................. 11 Alternative 1 – No -

Summary of GATWS 1973-2010

HISTORY of the GEORGIA CHAPTER OF THE WILDLIFE SOCIETY Established April 30, 1973 Semi-Annual Programs, Other Accomplishments, & Boards & Committees • MISSION: The Georgia Chapter of The Wildlife Society (Georgia TWS) is a professional organization dedicated to the scientific conservation of wildlife resources, and to furthering the education of those involved with, or interested in, wildlife conservation. Georgia TWS promotes rigorous professional ethics for wildlife scientists and managers, facilitates the exchange of technical information, and works to influence legislation impacting wildlife resources. Issue statements are developed, often in partnership with other conservation groups, and relayed to elected representatives of the Georgia and United States Constitutions and other people. • MEMBERSHIP: Georgia TWS has recently comprised of over 200 members representing universities, state, and federal agencies, conservation organizations, and the general public. Some members are involved with wildlife management in a professional capacity, while others are involved simply because of their interest in wild animals and the management of these species and their habitats. The Chapter officers function as the Executive Committee, and most of the organization's business is conducted via that body, with input from the general membership. However, there are numerous opportunities for non-elected members to contribute to the Chapter. • MEETINGS: Georgia TWS meets twice per year, spring and fall, in various locations around the state. Occasionally we meet jointly with other state chapters or other organizations. Meetings generally span two days, and feature presentations detailing current issues in wildlife research, management, and legislation. The meetings also address Chapter business, and a new crop of officers is elected at the spring meeting every two years. -

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 04/01/2017 to 06/30/2017 National Forests in Alabama This Report Contains the Best Available Information at the Time of Publication

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 04/01/2017 to 06/30/2017 National Forests in Alabama This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact National Forests in Alabama, Occurring in more than one District (excluding Forestwide) R8 - Southern Region Talladega Division New - Vegetation management In Progress: Expected:06/2017 06/2017 Scott Layfield Prescribed Burn Units (other than forest products) Comment Period Public Notice 256-362-2909 Environmental Assessment - Fuels management 07/03/2014 [email protected] EA Description: Addition of 9900 acres to its prescribed burning program for fuel reduction, ecosystem restoration and wildlife habitat improvement Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=45542 Location: UNIT - Talladega Ranger District, Shoal Creek Ranger District. STATE - Alabama. COUNTY - Cherokee, Clay, Cleburne, Talladega. LEGAL - Not Applicable. A total of 10 new burn unit as show on associated maps. National Forests in Alabama Bankhead Ranger District (excluding Projects occurring in more than one District) R8 - Southern Region Special Use Permit - Reggie - Special use management On Hold N/A N/A Mike Cook Watts Right-of-way 205-489-5111 CE [email protected] Description: Issue a special use permit for right-of-way to Reggie Watts for driveway and utility installation to private property. Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=40043 Location: UNIT - Bankhead Ranger District. STATE - Alabama. COUNTY - Winston. LEGAL - Section 23, T10S, R7W. Bankhead National Forest, Horseshoe Bend Area, Houston, Alabama, FS Road 123D1 and unnamed woods road. -

Table 6 - NFS Acreage by State, Congressional District and County

Table 6 - NFS Acreage by State, Congressional District and County State Congressional District County Unit NFS Acreage Alabama 1st Escambia Conecuh National Forest 29,179 1st Totals 29,179 2nd Coffee Pea River Land Utilization Project 40 Covington Conecuh National Forest 54,881 2nd Totals 54,921 3rd Calhoun Rose Purchase Unit 161 Talladega National Forest 21,412 Cherokee Talladega National Forest 2,229 Clay Talladega National Forest 66,763 Cleburne Talladega National Forest 98,750 Macon Tuskegee National Forest 11,348 Talladega Talladega National Forest 46,272 3rd Totals 246,935 4th Franklin William B. Bankhead National Forest 1,277 Lawrence William B. Bankhead National Forest 90,681 Winston William B. Bankhead National Forest 90,030 4th Totals 181,988 6th Bibb Talladega National Forest 60,867 Chilton Talladega National Forest 22,986 6th Totals 83,853 2018 Land Areas Report Refresh Date: 10/13/2018 Table 6 - NFS Acreage by State, Congressional District and County State Congressional District County Unit NFS Acreage 7th Dallas Talladega National Forest 2,167 Hale Talladega National Forest 28,051 Perry Talladega National Forest 32,796 Tuscaloosa Talladega National Forest 10,998 7th Totals 74,012 Alabama Totals 670,888 Alaska At Large Anchorage Municipality Chugach National Forest 248,417 Haines Borough Tongass National Forest 767,952 Hoonah-Angoon Census Area Tongass National Forest 1,974,292 Juneau City and Borough Tongass National Forest 1,672,846 Kenai Peninsula Borough Chugach National Forest 1,261,067 Ketchikan Gateway Borough Tongass -

Land Areas Report Refresh Date: 10/17/2020 Table 6 - NFS Acreage by State, Congressional District and County

Table 6 - NFS Acreage by State, Congressional District and County State Congressional District County Unit NFS Acreage Alabama 1st Escambia Conecuh National Forest 29,179 1st Totals 29,179 2nd Coffee Pea River Land Utilization Project 40 Covington Conecuh National Forest 54,887 2nd Totals 54,927 3rd Calhoun Rose Purchase Unit 161 Talladega National Forest 21,412 Cherokee Talladega National Forest 2,229 Clay Talladega National Forest 66,763 Cleburne Talladega National Forest 98,749 Macon Tuskegee National Forest 11,348 Talladega Talladega National Forest 46,272 3rd Totals 246,934 4th Franklin William B. Bankhead National Forest 1,277 Lawrence William B. Bankhead National Forest 90,681 Winston William B. Bankhead National Forest 90,030 4th Totals 181,987 6th Bibb Talladega National Forest 60,983 Chilton Talladega National Forest 23,821 6th Totals 84,804 2020 Land Areas Report Refresh Date: 10/17/2020 Table 6 - NFS Acreage by State, Congressional District and County State Congressional District County Unit NFS Acreage 7th Dallas Talladega National Forest 2,167 Hale Talladega National Forest 28,051 Perry Talladega National Forest 32,738 Tuscaloosa Talladega National Forest 10,998 7th Totals 73,954 Alabama Totals 671,786 Alaska At Large Anchorage Municipality Chugach National Forest 248,417 Haines Borough Tongass National Forest 767,860 Hoonah-Angoon Census Area Tongass National Forest 1,979,060 Juneau City and Borough Tongass National Forest 1,672,684 Kenai Peninsula Borough Chugach National Forest 1,261,065 Ketchikan Gateway Borough Tongass