Alabama's TREASURED Forests

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Apalachicola & Conecuh National Forests

Apalachicola & Conecuh National Forests Recreation Realignment Report Prepared by: Christine Overdevest & H. Ken Cordell August, 2001 Web Series: SRS-4901-2001-4 Web Series: SRS-4901-2001-4 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................. 1 Report Objectives ............................................................ 1 On Analysis Assumptions ...................................................... 1 Vision of Interactive Session: How to Use this Report .................................. 2 Report Contents .............................................................. 3 The Realignment Context ....................................................... 4 Recreation Realignment Step 1. - Population Analysis ................................................... 6 Step 2. - Recreation Participation Analysis and Segmentation of Activities ................. 11 Step 3. - Analysis of Fastest Growing Outdoor Recreation Activities ..................... 16 Step 4. - Recreation Participation Analysis by Demographic Strata ....................... 17 Step 5. - Summing Step 4 Activity Scores Across Demographic Strata ................... 40 Step 6. - Summing Activity Scores Over 3 Dimensions of Demand ....................... 41 Step 7. - Identifying Niche Activities ............................................. 43 Step 8. - Equity Analysis ..................................................... 44 Step 9. - Other Suppliers of Outdoor Recreation in your Market Area ................... 47 Step 10 - Summary Observations, -

Land Areas of the National Forest System, As of September 30, 2019

United States Department of Agriculture Land Areas of the National Forest System As of September 30, 2019 Forest Service WO Lands FS-383 November 2019 Metric Equivalents When you know: Multiply by: To fnd: Inches (in) 2.54 Centimeters Feet (ft) 0.305 Meters Miles (mi) 1.609 Kilometers Acres (ac) 0.405 Hectares Square feet (ft2) 0.0929 Square meters Yards (yd) 0.914 Meters Square miles (mi2) 2.59 Square kilometers Pounds (lb) 0.454 Kilograms United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Land Areas of the WO, Lands National Forest FS-383 System November 2019 As of September 30, 2019 Published by: USDA Forest Service 1400 Independence Ave., SW Washington, DC 20250-0003 Website: https://www.fs.fed.us/land/staff/lar-index.shtml Cover Photo: Mt. Hood, Mt. Hood National Forest, Oregon Courtesy of: Susan Ruzicka USDA Forest Service WO Lands and Realty Management Statistics are current as of: 10/17/2019 The National Forest System (NFS) is comprised of: 154 National Forests 58 Purchase Units 20 National Grasslands 7 Land Utilization Projects 17 Research and Experimental Areas 28 Other Areas NFS lands are found in 43 States as well as Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. TOTAL NFS ACRES = 192,994,068 NFS lands are organized into: 9 Forest Service Regions 112 Administrative Forest or Forest-level units 503 Ranger District or District-level units The Forest Service administers 149 Wild and Scenic Rivers in 23 States and 456 National Wilderness Areas in 39 States. The Forest Service also administers several other types of nationally designated -

Introduction

00i-xvi_Mohl-East-00-FM 2/18/06 8:25 AM Page xv INTRODUCTION During the rapid development of the United States after the American Rev- olution, and during most of the 1900s, many forests in the United States were logged, with the logging often followed by devastating fires; ranchers converted the prairies and the plains into vast pastures for livestock; sheep were allowed to venture onto heretofore undisturbed alpine areas; and great amounts of land were turned over in an attempt to find gold, silver, and other minerals. In 1875, the American Forestry Association was born. This organization was asked by Secretary of the Interior Carl Schurz to try to change the con- cept that most people had about the wasting of our natural resources. One year later, the Division of Forestry was created within the Department of Agriculture. However, land fraud continued, with homesteaders asked by large lumber companies to buy land and then transfer the title of the land to the companies. In 1891, the American Forestry Association lobbied Con- gress to pass legislation that would allow forest reserves to be set aside and administered by the Department of the Interior, thus stopping wanton de- struction of forest lands. President Benjamin Harrison established forest re- serves totaling 13 million acres, the first being the Yellowstone Timberland Reserve, which later became the Shoshone and Teton national forests. Gifford Pinchot was the founder of scientific forestry in the United States, and President Theodore Roosevelt named him chief of the Forest Ser- vice in 1898 because of his wide-ranging policy on the conservation of nat- ural resources. -

Thematic Maps

Title Author/Publisher Date Scale Map Case Drawer Folder Notes Island of Puerto Rico Corps of Engineers, U.S. Army 1942 1:300,000 23 1 Puerto Rico - Misc Mapa de Puerto Rico American Map Corporation 1988 23 1 Puerto Rico - Misc United States Department of Puerto Rico E Islas Limitrofes The Interior Geological Survey 1971 1:120,000 23 1 Puerto Rico - Misc Protected Natural Areas of Puerto Rico US Department of Agriculture 2011 1:240,000 23 1 Puerto Rico - Misc Essential Geography of the United States of America Imus Cartographics 2010 1:4,000,000 23 1 United States - General Reference Maps G3700 2010 .I4 North American Environment Atlas: Mapping our shared British Oceanographic Data environment Centre 2003 1:10,000,000 23 1 United States - General Reference Maps United States American Map Corporation 1986 23 1 United States - General Reference Maps United States (Larger Map) American Map Corporation 1986 23 1 United States - General Reference Maps (No Clear Title) Map Of United States Esselte Map Service 1990 1:4,000,000 23 1 United States - General Reference Maps United States of America Imprime en Alleagne par 1986 1:15,000,000 23 1 United States - General Reference Maps United States 1990 1:15,000,000 23 1 United States - General Reference Maps United States of America Rand McNally and Company 1:4,000,000 23 1 United States - General Reference Maps United States : With Highways American Map Corporation 1992 23 1 United States - General Reference Maps United States USGS 1972 1:2,500,000 23 1 United States - General Reference Maps General -

97 H.R.6011 Title: a Bill to Designate Certain Lands in the Bankhead National Forest, Alabama, As a Wilderness Area and to Incor

97 H.R.6011 Title: A bill to designate certain lands in the Bankhead National Forest, Alabama, as a wilderness area and to incorporate such wilderness area into the Sipsey Wilderness. Sponsor: Rep Flippo, Ronnie G. [AL-5] (introduced 3/31/1982) Cosponsors (3) Latest Major Action: 11/30/1982 Senate committee/subcommittee actions. Status: Subcommittee on Public Lands and Reserved Water. Hearings held. SUMMARY AS OF: 8/4/1982--Passed House amended. (There are 3 other summaries) (Measure passed House, amended, roll call #240 (349-59)) Alabama Wilderness Act of 1982 - Designates certain lands in the Talladega National Forest in Alabama as the Cheaha Wilderness. Designates certain lands in the Bankhead National Forest in Alabama as part of the Sipsey Wilderness. States that the RARE II final environmental impact statement (dated January 1979) shall not be subject to judicial review with respect to national forest system lands in Alabama. Provides that the second roadless area review and evaluation of national forest lands in Alabama shall be treated as an adequate consideration of their suitability for inclusion in the National Wilderness Preservation System. Provides that areas not designated as wilderness by this Act or remaining in further planning need not be managed so as to protect their wilderness character pending revision of land management plans required by the Forest and Rangeland Renewable Resources Planning Act of 1974. Prohibits the Department of Agriculture from conducting any further statewide roadless area review and evaluation of national forest lands in Alabama to determine their suitability as wilderness without express congressional authorization. MAJOR ACTIONS: 3/31/1982 Introduced in House 7/20/1982 Reported to House (Amended) by House Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs. -

Appendix 1. Property Ids and Names (Sorted by Name)

Appendix 1. Property IDs and Names (sorted by name) Property Name Property ID State Alexander State Forest AXSF LA Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge ARNWR NC Angelina Ranger District, Angelina National Forest ANRDANF TX Apalachicola Ranger District, Apalachicola National Forest ARDANF FL Avalon Plantation AVPL FL Avon Park Air Force Range APAFR FL Bates Hill Plantation BHPL SC Bienville Ranger District, Bienville National Forest BRDBNF MS Big Branch Marsh National Wildlife Refuge BBMNWR LA Big Cypress National Preserve BCNP FL Black Bayou Lake NWR BBLNWR LA Blackwater River State Forest BRSF FL Bladen Lakes State Forest BLSF NC Blue Tract BT NC Brookgreen Gardens BG SC Brushy Creek Experimental Forest IPBCEF TX Bull Creek & Triple N Ranch Wildlife Management Areas BCWMA FL Burroughs & Chapin Company, Grand Dunes BCCGD SC Burroughs & Chapin Company, Horry County BCCHC SC Camp Blanding CB FL Camp Mackall CM NC Carolina Sandhills National Wildlife Refuge CSNWR SC Catahoula Ranger District, Kisatchie National Forest CRDKNF LA Cheraw State Fish Hatchery CSFH SC Cheraw State Park CSP SC Chickasawhay Ranger District, DeSoto National Forest CRDDNF MS Conecuh National Forest CNF AL Cooks Branch Conservancy CBC TX Croatan Ranger District, Croatan National Forest CRDCNF NC Crosett Experimental Forest CEF AR Cumberland County Private Lands CCPL NC D'Arbonne National Wildlife Refuge DNWR LA Dare County Bombing Range DCBR NC Davy Crockett National Forest DCNF TX Desoto Ranger District, Desoto National Forest DRDDNF MS Dupuis Wildllife and Environmental Area DWEA FL Eglin Air Force Base EAFB FL Enon and Sehoy Plantation ESPL AL Escape Ranch ERANCH FL Evangeline Unit, Calcasieu RD, Kisatchie National Forest EUCRDKNF LA Fairchild State Forest FSF TX Felsenthal National Wildlife Refuge FNWR AR Fort Benning FTBN GA Fort Bragg FTBG NC Fort Gordon FTGD GA Fort Jackson FTJK SC Fort Polk FTPK LA Fort Stewart FTST GA Francis Marion National Forest FMNF SC Fred C. -

At-Risk Species Assessment on Southern National Forests, Refuges, and Other Protected Areas

David Moynahan | St. Marks NWR At-Risk Species Assessment on Southern National Forests, Refuges, and Other Protected Areas National Wildlife Refuge Association Mark Sowers, Editor October 2017 1001 Connecticut Avenue NW, Suite 905, Washington, DC 20036 • 202-417-3803 • www.refugeassociation.org At-Risk Species Assessment on Southern National Forests, Refuges, and Other Protected Areas Table of Contents Introduction and Methods ................................................................................................3 Results and Discussion ......................................................................................................9 Suites of Species: Occurrences and Habitat Management ...........................................12 Progress and Next Steps .................................................................................................13 Appendix I: Suites of Species ..........................................................................................17 Florida Panhandle ............................................................................................................................18 Peninsular Florida .............................................................................................................................28 Southern Blue Ridge and Southern Ridge and Valley ...............................................................................................................................39 Interior Low Plateau and Cumberland Plateau, Central Ridge and Valley ...............................................................................................46 -

Environmental Assessment for Tuskegee Upland Pine Restoration

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Southern Region Environmental Assessment March for Tuskegee Upland Pine 2014 Restoration Tuskegee National Forest: Macon County For Project Information Contact: Eugene Brooks, Team Leader 2946 Chestnut Street Montgomery, AL 36107 334-241-8149 Tuskegee Upland Pine Restoration Project Table of Contents Chapter 1 – Purpose and Need .........................................................................................................1 Background .............................................................................................................................................. 1 Purpose and Need for Action .................................................................................................................. 5 Project Area Description .......................................................................................................................... 7 Proposed Action ....................................................................................................................................... 7 Decision Framework .............................................................................................................................. 11 Public Involvement ................................................................................................................................. 11 Chapter 2 – Alternatives .................................................................................................................. 11 Alternative 1 – No -

Summary of GATWS 1973-2010

HISTORY of the GEORGIA CHAPTER OF THE WILDLIFE SOCIETY Established April 30, 1973 Semi-Annual Programs, Other Accomplishments, & Boards & Committees • MISSION: The Georgia Chapter of The Wildlife Society (Georgia TWS) is a professional organization dedicated to the scientific conservation of wildlife resources, and to furthering the education of those involved with, or interested in, wildlife conservation. Georgia TWS promotes rigorous professional ethics for wildlife scientists and managers, facilitates the exchange of technical information, and works to influence legislation impacting wildlife resources. Issue statements are developed, often in partnership with other conservation groups, and relayed to elected representatives of the Georgia and United States Constitutions and other people. • MEMBERSHIP: Georgia TWS has recently comprised of over 200 members representing universities, state, and federal agencies, conservation organizations, and the general public. Some members are involved with wildlife management in a professional capacity, while others are involved simply because of their interest in wild animals and the management of these species and their habitats. The Chapter officers function as the Executive Committee, and most of the organization's business is conducted via that body, with input from the general membership. However, there are numerous opportunities for non-elected members to contribute to the Chapter. • MEETINGS: Georgia TWS meets twice per year, spring and fall, in various locations around the state. Occasionally we meet jointly with other state chapters or other organizations. Meetings generally span two days, and feature presentations detailing current issues in wildlife research, management, and legislation. The meetings also address Chapter business, and a new crop of officers is elected at the spring meeting every two years. -

Natural Resources

Natural Heritage in the MSNHA The Highland Rim The Muscle Shoals National Heritage Area is located within the Highland Rim section of Alabama. The Highland Rim is the southernmost section of a series low plateaus that are part of the Appalachian Mountains. The Highland Rim is one of Alabama’s five physiographic regions, and is the smallest one, occupying about 7 percent of the state. The Tennessee River The Tennessee River is the largest tributary off the Ohio River. The river has been known by many names throughout its history. For example, it was known as the Cherokee River, because many Cherokee tribes had villages along the riverbank. The modern name of the river is derived from a Cherokee word tanasi, which means “river of the great bend.” The Tennessee River has many dams on it, most of them built in the 20th century by the Tennessee Valley Authority. Due to the creation of these dams, many lakes have formed off the river. One of these is Pickwick Lake, which stretches from Pickwick Landing Dam in Tennessee, to Wilson Dam in the Shoals area. Wilson Lake and Wheeler Lake are also located in the MSNHA. Additionally, Wilson Dam Bear Creek Lakes were created by four TVA constructed dams on Bear Creek and helps manage flood conditions and provides water to residents in North Alabama. Though man-made, these reservoirs have become havens for fish, birds, and plant life and have become an integral part of the natural heritage of North Alabama. The Muscle Shoals region began as port area for riverboats travelling the Tennessee River. -

100 H.R.5395 Title: a Bill to Designate the Sipsey River As a Component Of

100 H.R.5395 Title: A bill to designate the Sipsey River as a component of the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System, to designate certain areas as additions to the Sipsey Wilderness, to designate certain areas as additions to the Cheaha Wilderness, and to preserve over thirty thousand acres of pristine natural treasures in the Bankhead National Forest for the aesthetic and recreational benefit of future generations of Alabamians, and for other purposes. Sponsor: Rep Flippo, Ronnie G. [AL-5] (introduced 9/27/1988) Cosponsors (1) Related Bills: S.2838 Latest Major Action: 10/28/1988 Became Public Law No: 100-547. SUMMARY AS OF: 10/6/1988--Passed House amended. (There is 1 other summary) (Measure passed House, amended) Sipsey Wild and Scenic River and Alabama Wilderness Addition Act of 1988 - Title I: Wild and Scenic Rivers Designation - Amends the Wild and Scenic River Act to designate specified segments of the Sipsey Fork River, Alabama, as components of the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. Directs the Secretary of Agriculture to study the feasibility of constructing a dam to establish a lake for recreational use within the Bankhead National Forest. Directs the Secretary to monitor waters flowing into Lewis Smith Lake and take appropriate actions to control any conditions causing injurious water quality. Title II: Wilderness Designation - Designates the following lands in Alabama as components of the National Wilderness Preservation System: (1) the Sipsey Wilderness in the William B. Bankhead National Forest; and (2) the Cheaha Wilderness in the Talladega National Forest. Authorizes the Secretary to take measures to control fire, insects, and diseases within the Sipsey Wilderness. -

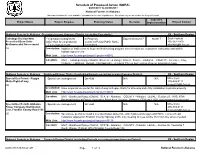

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 04/01/2017 to 06/30/2017 National Forests in Alabama This Report Contains the Best Available Information at the Time of Publication

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 04/01/2017 to 06/30/2017 National Forests in Alabama This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact National Forests in Alabama, Occurring in more than one District (excluding Forestwide) R8 - Southern Region Talladega Division New - Vegetation management In Progress: Expected:06/2017 06/2017 Scott Layfield Prescribed Burn Units (other than forest products) Comment Period Public Notice 256-362-2909 Environmental Assessment - Fuels management 07/03/2014 [email protected] EA Description: Addition of 9900 acres to its prescribed burning program for fuel reduction, ecosystem restoration and wildlife habitat improvement Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=45542 Location: UNIT - Talladega Ranger District, Shoal Creek Ranger District. STATE - Alabama. COUNTY - Cherokee, Clay, Cleburne, Talladega. LEGAL - Not Applicable. A total of 10 new burn unit as show on associated maps. National Forests in Alabama Bankhead Ranger District (excluding Projects occurring in more than one District) R8 - Southern Region Special Use Permit - Reggie - Special use management On Hold N/A N/A Mike Cook Watts Right-of-way 205-489-5111 CE [email protected] Description: Issue a special use permit for right-of-way to Reggie Watts for driveway and utility installation to private property. Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=40043 Location: UNIT - Bankhead Ranger District. STATE - Alabama. COUNTY - Winston. LEGAL - Section 23, T10S, R7W. Bankhead National Forest, Horseshoe Bend Area, Houston, Alabama, FS Road 123D1 and unnamed woods road.