Post Tracheostomy and Post Intubation Tracheal Stenosis: Report of 31

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Posterior Glottic Stenosis in Adults

Original Articles Posterior Glottic Stenosis in Adults Michael Wolf MD, Adi Primov-Fever MD, Yoav P. Talmi MD FACS and Jona Kronenberg MD Department of Otorhinolaryngology & Head Neck Surgery, Sheba Medical Center, Tel Hashomer, Israel Affiliated to Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv, Israel Key words: larynx, vocal cords, stenosis, fixation, laryngoplasty Abstract entiation between vocal cord paralysis and fixation [3,4], although Background: Posterior glottic stenosis is a complication of some patients survived complex central nervous system and prolonged intubation, manifesting as airway stenosis that may mimic peripheral organ injuries, long courses of mechanical ventilation, bilateral vocal cord paralysis. It presents a variety of features that oral or nasal intubation, and nasogastric tubing. These may result mandate specific surgical interventions. in combined pathologies of both paralysis and fixation, or they Objectives: To summarize our experience with PSG and its working diagnosis. may mask the alleged simplicity of making a diagnosis based Methods: We conducted a retrospective review of a cohort of solely on clinical grounds. The extent of scarring dictates the adult patients with PGS operated at the Sheba Medical Center extent of surgical intervention. While endoscopic lysis of the scar between 1994 and 2006. is appropriate for grade 1, complex laryngoplasty procedures are Results: Ten patients were diagnosed with PGS, 6 of whom mandated for grades 2 to 4 [3]. also had stenosis at other sites of -

Idiopathic Subglottic Stenosis: a Review

1111 Editorial Section of Interventional Pulmonology Idiopathic subglottic stenosis: a review Carlos Aravena1,2, Francisco A. Almeida1, Sanjay Mukhopadhyay3, Subha Ghosh4, Robert R. Lorenz5, Sudish C. Murthy6, Atul C. Mehta1 1Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Respiratory Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, USA; 2Department of Respiratory Diseases, Faculty of Medicine, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile; 3Department of Pathology, Robert J. Tomsich Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Institute, 4Department of Diagnostic Radiology, 5Head and Neck Institute, 6Department of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Heart and Vascular Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, USA Contributions: (I) Conception and design: C Aravena, AC Mehta; (II) Administrative support: All authors; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: All authors; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: C Aravena, AC Mehta; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: All authors; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors. Correspondence to: Atul C. Mehta, MD, FCCP. Lerner College of Medicine, Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Respiratory Institute, Cleveland Clinic, 9500 Euclid Ave, A-90, Cleveland, OH 44195, USA. Email: [email protected]. Abstract: Idiopathic subglottic stenosis (iSGS) is a fibrotic disease of unclear etiology that produces obstruction of the central airway in the anatomic region under the glottis. The diagnosis of this entity is difficult, usually delayed and confounded with other common respiratory diseases. No apparent etiology is identified even after a comprehensive workup that includes a complete history, physical examination, pulmonary function testing, auto-antibodies, imaging studies, and endoscopic procedures. This approach, however, helps to exclude other conditions such as granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA). It is also helpful to characterize the lesion and outline management strategies. -

Paediatric Airway Problems

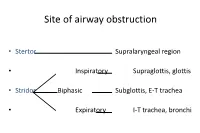

Site of airway obstruction • Stertor Supralaryngeal region • Inspiratory Supraglottis, glottis • Stridor Biphasic Subglottis, E-T trachea • Expiratory I-T trachea, bronchi Investigation of Stridor • History • Examination • Radiological investigations • Endoscopy History • Neonatal intubation • Stridor / stertor • Voice / cry • Cough / cyanotic attacks • Feeding difficulties • Failure to thrive Examination • Pallor, cyanosis • Tracheal tug, sternal recession, intercostal / subcostal recession • Pectus excavatum, Harrison’s sulci • Stridor / stertor • Voice / cry • Cough Site of Airway Obstruction Stridor Voice Cough Supralaryngeal Stertor Muffled - region Supraglottis, Inspiratory Hoarse Barking glottis Subglottis, E-T Biphasic Normal Brassy trachea I-T trachea, Expiratory Normal + bronchi Site of Airway Obstruction • Pharyngeal (stertor): - worse when asleep • Laryngeal, tracheal or bronchial (stridor): - worse when awake, especially if stressed Radiological investigations • Soft-tissue lateral neck X-ray • PA chest X-ray • Cincinnati (high-kv filter) view • ? Barium swallow • ? Bronchogram Endoscopy • The definitive investigation for a child with stridor Endoscopy • Awake flexible fibreoptic laryngoscopy • Suitable for infants using simple restraint • Screening investigation for laryngomalacia • May be helpful in assessing vocal cord palsy • But only gives a view of the supraglottis • Does not exclude coexisting lower airway pathology Endoscopy • Microlaryngoscopy + Bronchoscopy • “The Gold Standard” Total airway endoscopies at GOS 9,341 -

Imaging of the Trachea

Keynote Lecture Series Imaging of the trachea Jo-Anne O. Shepard, Efren J. Flores, Gerald F. Abbott Division of Thoracic Imaging, Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA Correspondence to: Jo-Anne O. Shepard, MD. Thoracic Imaging, Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Founders 202, 55 Fruit Street, Boston, MA 02114, USA. Email: [email protected]. Numerous benign and malignant tracheal diseases may affect the trachea primarily and secondarily. While the posterior anterior (PA) and lateral chest radiograph is the conventional study for initial evaluation of the trachea and central airways, findings may not always be apparent on conventional radiographs, and further evaluation with cross sectional imaging is usually necessary. Computed tomography (CT) is the imaging modality of choice for imaging the trachea and bronchi. Familiarity with the imaging appearances of the normal and diseased trachea will enhance diagnostic evaluation. Keywords: Trachea; tracheal stenosis; tracheal tumor; tracheomalacia Submitted Jan 09, 2018. Accepted for publication Feb 27, 2018. doi: 10.21037/acs.2018.03.09 View this article at: http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/acs.2018.03.09 Introduction mediastinal structures away from the trachea. Visualization of tracheal abnormalities can also be improved by high The trachea extends from the cricoid cartilage to the kilovoltage technique (140 kV). Evaluation of the trachea carina and usually measures 10–12 cm in length. The extra and central airways should be carefully performed on all thoracic trachea is (2–4 cm in length) and transitions to patients presenting with symptoms of stridor, wheezing, the intrathoracic trachea (6–9 cm in length) as it passes “adult-onset” asthma, hemoptysis or recurrent pneumonia. -

Laryngeal Stenosis and Laryngomalacia Treated with a Silicone Stent in a Prematurely Delivered Child: a Case Report

Journal of Medical Sciences. May 3, 2021 - Volume 9 | Issue 4. Electronic - ISSN: 2345-0592 Medical Sciences 2021 Vol. 9 (4), p. 216-220 Laryngeal stenosis and laryngomalacia treated with a silicone stent in a prematurely delivered child: a case report Jurgita Borodičienė¹, Eglė Žukauskaitė², Matas Kalinauskas², Marius Kašėta³, Andrius Macas¹ ¹ Department of Anesthesiology, Lithuanian University of Health Sciences, Eiveniu str. 2, LT-50009, Kaunas, Lithuania ² Faculty of Medicine, Academy of Medicine, Lithuanian University of Health Sciences, Eiveniu str. 2, LT-50009 Kaunas, Lithuania ³ Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Lithuanian University of Health Sciences, Eiveniu str. 2, LT-50009, Kaunas, Lithuania Abstract Background. Preterm birth is one of the most significant risk factors for infants’ laryngeal stenosis (LS), which can occur as laryngomalacia (LM). LS can be defined as a partial or circumferential narrowing of the endolaryngeal airway and may be congenital or acquired. This condition cause various symptoms such as stridor, dyspnea and respiratory distress, therefore early intubation is required. Most of the patients with LS or LM outgrow their disease, but the rest of them need surgical help. Objectives. The aim of this article is to present a successful surgical treatment for preterm infant with LS. Methods: case presentation and an analysis of literature. Research of articles in “PubMed”, “Google Scholar” databases with keywords used as follows: “Laryngeal stenosis”, “Laryngomalacia”, “Pediatric stent”, “Premature delivery”, “Endolaryngeal microsurgery”. Case presentation. 3-year-old male presented the hospital with diagnosed LM and for laryngeal stent insertion surgery. The patient was born at 26 gestational weeks and was treated for sepsis during the neonatal period, was intubated at birth because of severe respiratory distress, had 6 endolaryngeal microsurgeries (EM) and received Kenalog injections 5 times. -

Management of Benign Central Airway Obstruction

Review Article Page 1 of 20 Management of benign central airway obstruction Van K. Holden1, Colleen L. Channick2 1Division of Thoracic Surgery and Interventional Pulmonology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, 2Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA Contributions: (I) Conception and design: All authors; (II) Administrative support: All authors; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: All authors; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: All authors; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: All authors; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors. Correspondence to: Colleen L. Channick. 55 Fruit Street, Boston, MA 02114-2696, USA. Email: [email protected]. Abstract: There are a variety of etiologies of benign central airway obstruction, including traumatic, inflammatory, infectious, and systemic disorders. Presentation with non-specific respiratory symptoms often leads to delayed identification and management. Therapeutic strategies include bronchoscopic and surgical interventions; however, recurrence of airway obstruction leads to significant morbidity and mortality. We present a review of the etiology, diagnosis and management of several causes of benign airway obstruction. Keywords: Airway obstruction; bronchoscopy; tracheal stenosis Received: 14 March 2018; Accepted: 12 July 2018; Published: 19 July 2018. doi: 10.21037/amj.2018.07.04 View this article at: http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/amj.2018.07.04 Introduction by extrinsic compression of the airway. Benign CAO may also occur with cartilaginous malacia involving segmental Benign central airway obstruction (CAO) is defined as a or diffuse weakness of the tracheal and bronchial walls non-malignant disease process resulting in narrowing of the and excessive dynamic airway collapse associated with trachea and main stem bronchi. -

Alexander Gelbard, MD Laryngotracheal Stenosis (LTS)

Headmirror’s ENT in a Nutshell Laryngotracheal Stenosis Expert: Alexander Gelbard, MD Laryngotracheal Stenosis (LTS): general term for multiple disease processes with common physiologic end-point that result in ventilator restriction from luminal narrowing of the larynx, subglottis, or trachea causing a fixed extra-thoracic restriction of pulmonary ventilation Presentation (2:46) - LTS: Many causes, all anatomic/clinical exam similar. Etiology important as it often predicts outcome. 1. Iatrogenic (70%) – intubation, tracheostomy 2. Autoimmune (15%) – collagen vascular disease GPA/Wegner’s, relapsing polychondritis 3. Idiopathic (15%) 4. Other (rare) - trauma, radiation, infection - Symptoms o Dyspnea o Cough o Dysphonia o Trouble swallowing - Differential diagnosis (4:38) o Benign tumor: epithelial tumor (papilloma/cyst), non-epithelial tumor (schwannoma, neurofibroma, etc.) o Malignancy: squamous cell carcinoma, chondrosarcoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma o Intrinsic pulmonary disease: asthma, ILD, IPF, infection Pathophysiology (17:25) - Mucosal fibrosis: sustained inflammatory cell activation/infiltration, accumulation of fibrous connective tissue of extracellular matrix - Mucosal involvement and cartilaginous involvement. Latter can decrease structural integrity. - Histopathology (does not differentiate sub-type, help understand active inflammation): sub- epithelial inflammation with lymphocytic infiltrate, fibrosis of lamina propria with excess collagen. Granulation tissue with neovascularization o Iatrogenic: Inflammation cascade from -

Laryngotracheal Stenosis Management: a 16-Year Experience

Clinical Study Ear, Nose & Throat Journal 1–8 ª The Author(s) 2019 Laryngotracheal Stenosis Management: Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions A 16-Year Experience DOI: 10.1177/0145561319873593 journals.sagepub.com/home/ear Jonathan Woliansky, MBBS (Hons)1,2 , Paul Paddle, MBBS (Hons), FRACS1,2, and Debra Phyland, PhD, FSPAA1,2 Abstract In recent years, it has become increasingly apparent that the laryngotracheal stenosis (LTS) cohort comprises distinct etiological subgroups; however, treatment of the disease remains heterogeneous with limited research to date assessing predictors of treatment outcome. We aim to assess clinical and surgical predictors of endoscopic treatment outcome for LTS, as well as to further characterize the disease population. A retrospective chart review of adult patients with LTS presenting over a 16-year period was conducted. Seventy-five patients were identified and subdivided into 4 etiologic subgroups: iatrogenic, idiopathic, autoimmune, and ‘‘other’’ groups. Statistical comparison of iatrogenic and idiopathic groups was performed. Subsequently, stepwise logistic regression was employed to examine the association between clinical/surgical factors and treatment outcome, as measured by tracheostomy incidence and dependence. We demonstrate that patients with iatrogenic LTS were significantly more morbid (P < .001) and had worse disease, with significantly greater percentage stenosis (P ¼ .015) and increased incidence of tracheostomy (P < .001). Analyzing the predictive effect of clinical and surgical variables on endoscopic treatment outcome, we have shown that when adjusted for age, sex, and iatrogenic etiology, patients with an American Society of Anesthesiologist score >2 were significantly more likely to undergo tracheostomy (adjusted odds ratio ¼ 11.23, 95% confidence interval [CI] ¼ 1.47- 86.17). -

Appendices A

Appendices A. Search Strategy Table A-1. Search strategy for Key Question 1 Search terms Result "PEP therapy"[tiab] OR "PEP mask"[tiab] OR "Oscillating PEP"[tiab] OR "Chest Wall Oscillation"[mh] 2981 OR "postural drainage"[tiab] OR "Drainage, Postural"[mh] OR ((respiratory[tiab] OR lung[tiab] OR Lung[mh] OR chest[tiab]) AND ("Physical Therapy Modalities"[Mesh:NoExp] OR "physical therapy"[tiab] OR physiotherapy[tiab])) OR "HFCC"[tiab] OR ("high frequency"[tiab] AND chest[tiab] AND (compression[tiab] OR oscillation[tiab])) OR "intrapulmonary percussive ventilation"[tiab] OR Frequencer[tiab] OR "lung flute"[tiab] OR autogenic drainage[tiab] OR ACBT[tiab] OR "active cycle of breathing"[tiab] OR "cough assist"[tiab] OR "cough assistance"[tiab] OR "assisted cough"[tiab] OR "MI-E"[tiab] OR "mechanical insufflation-exsufflation"[tiab] OR "thoracic squeeze"[tiab] ((Positive-Pressure Respiration[mh] OR "positive expiratory pressure"[tiab] OR Flutter[tiab] OR 3696 Quake[tiab] OR Cornet[tiab] OR "RC-Cornet"[tiab] OR Acapella[tiab]OR Percussion[mh] OR percussion[tiab] OR percussing[tiab] OR Vibration[mh] OR vibration[tiab] OR oscillating[tiab] OR oscillation[tiab] OR Sound[mh] OR "sound waves"[tiab] OR Bronchoscopy[mh] OR Suction[mh] OR suction*[tiab] OR IPV[tiab] OR "Breathing Exercises"[mh] OR "non-drug"[tiab] OR "non- pharmacological"[tiab]) AND (Airway Obstruction/therapy[mh] OR "airway clearance"[tiab] OR "airway clearing"[tiab] OR "airway obstruction"[tiab] OR "airflow obstruction"[tiab] OR "lung clearance"[tiab] OR "lung clearing"[tiab] OR "sputum -

Management of Airway Complications Following Lung Transplantation

Review Article Page 1 of 12 Management of airway complications following lung transplantation Laura Frye1, E. Kate Phillips2 1Division of Allergy, Pulmonary, and Critical Care Medicine, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USA; 2Department of Internal Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA Contributions: (I) Conception and design: None; (II) Administrative support: None; (III) Provision of study material or patients: None; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: None; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: None; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors. Correspondence to: Laura Frye, MD. Assistant Professor of Medicine, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA. Email: [email protected]. Abstract: Airway complications (ACs) following lung transplantation are a significant source of morbidity and mortality. The incidence of ACs has decreased over the years with advances in surgical technique. Airway ischemia is thought to be a main risk factor for formation of ACs, although other risk factors are being studied. There is not yet a universally accepted system for grading ACs. These complications include bronchial stenosis, airway necrosis or dehiscence, fistula formation, anastomotic infection, granulation tissue formation, and tracheobronchomalacia. The management of ACs requires a multimodal approach. Bronchoscopic management options include balloon bronchoplasty, cryotherapy, and stent placement. Medical management including antibiotics, mucus clearance techniques and positive pressure ventilation also play a role; surgical management is considered in select cases. This article reviews the risk factors associated with the development of ACs, the clinical presentation and classification of ACs, and current management paradigms. Keywords: Lung transplant; bronchoscopy; bronchial stenosis; airway necrosis; airway dehiscence; stent Received: 10 August 2019; Accepted: 26 November 2019; Published: 10 July 2020. -

Outcomes After Endoscopic Dilation of Laryngotracheal Stenosis: an Analysis of ACS-NSQIP Avni Bavishi, MS, Emily Boss, MD, MPH, Rahul K

Original Research Outcomes After Endoscopic Dilation of Laryngotracheal Stenosis: An Analysis of ACS-NSQIP Avni Bavishi, MS, Emily Boss, MD, MPH, Rahul K. Shah, MD, MBA, and Jennifer Lavin, MD, MS ABSTRACT Background: Endoscopic management of pediatric subglottic Results: 171 endoscopic and 116 open procedures were stenosis is common; however, no multiinstitutional identified. Mean age at endoscopic and open procedures was studies have assessed its perioperative outcomes. 4.1 (SEM = 0.37) and 5.4 years (SEM = 0.40). Mean LOS The American College of Surgeon’s National Surgical was shorter after endoscopic procedures (5.5 days, SEM = Quality Improvement Program – Pediatric (ACS-NSQIP-P) 1.13 vs. 11.3 days SEM = 1.01, P < 0.001). Open procedures represents a source of such data. had higher rates of reintubation (OR = 7.41, P = 0.026) and Objective: To investigate 30-day outcomes of endoscopic reoperation (OR = 3.09, P = 0.009). In patients undergoing dilation of the pediatric airway and to compare these endoscopic dilation, children < 1 year were more likely to outcomes to those seen with open reconstruction require readmission (OR = 4.21, P = 0.03) and reoperation techniques. (OR = 4.39, P = 0.03) when compared with older children. Methods: Current procedural terminology (CPT) codes were Conclusion: Open airway reconstruction is associated with queried for endoscopic or open airway reconstruction longer LOS and increased reintubations and reoperations, in the 2015 ACS-NSQIP-P Public Use File (PUF). Demo- suggesting a possible opportunity to improve value in health graphics and 30-day events were abstracted to compare care in the appropriately selected patient. -

Complications of Airway Management

Complications of Airway Management Paulette C Pacheco-Lopez MD, Lauren C Berkow MD, Alexander T Hillel MD, and Lee M Akst MD Introduction Methods Results Risk Factors Injury by Anatomic Site Late Complications of Intubation Special Considerations Conclusion Although endotracheal intubation is commonly performed in the hospital setting, it is not without risk. In this article, we review the impact of endotracheal intubation on airway injury by describing the acute and long-term sequelae of each of the most commonly injured anatomic sites along the respiratory tract, including the nasal cavity, oral cavity, oropharynx, larynx, and trachea. Injuries covered include nasoseptal injury, tongue injury, dental injury, mucosal lacerations, vocal cord immobility, and laryngotracheal stenosis, as well as tracheomalacia, tracheoinnominate, and tra- cheoesophageal fistulas. We discuss the proposed mechanisms of tissue damage that relate to each and present their most common clinical manifestations, along with their respective diagnostic and management options. This article also includes a review of complications of airway management pertaining to video laryngoscopy and supraglottic airway devices. Finally, potential strategies to prevent intubation-associated injuries are outlined. Key words: intubation; airway complications; subglottic stenosis; vocal cord injury [Respir Care 2014;59(6):1006–1021. © 2014 Daedalus Enterprises] Introduction health care professionals throughout the world and is a relatively safe maneuver. However, endotracheal intuba- The establishment of an adequate airway is integral to tion is not risk-free, and its complications are well de- managing patients both in the elective operating room set- scribed in the literature. These can range from minor soft ting and in the emergent nonoperating room setting.