A Cosmic Shift in the Screwtape Letters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Face of the Materialist Magician: Lewis, Tolkien, and the Art of Crossing Perilous Streets

Volume 35 Number 1 Article 2 10-15-2016 The Face of the Materialist Magician: Lewis, Tolkien, and the Art of Crossing Perilous Streets Robert Boenig Texas A&M University in College Station, TX Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Boenig, Robert (2016) "The Face of the Materialist Magician: Lewis, Tolkien, and the Art of Crossing Perilous Streets," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 35 : No. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol35/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Plenary address, Mythcon 47. Concerns the character of the “Materialist Magician” (Screwtape’s term) in Tolkien and Lewis—the Janus-like figure who looks backward to magic and forward to scientism, without the moral core to reconcile his liminality. -

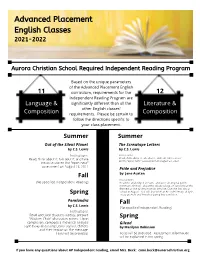

Required Independent Reading Program

Advanced Placement English Classes 2021-2022 Aurora Christian School Required Independent Reading Program Based on the unique parameters of the Advanced Placement English 11 curriculum, requirements for the 12 Independent Reading Program are Language & significantly different than all the Literature & other English classes' Composition requirements. Please be certain to Composition follow the directions specific to your class placement. Summer Summer Out of the Silent Planet The Screwtape Letters by C.S. Lewis by C.S. Lewis Instructions: Instructions: Read, think about it, talk abut it, and take Read, think about it, talk abut it, and take notes to use on the "open-note" assessment on August 23, 2021 notes to use on the "open-note" assessment on August 23, 2021 Pride and Prejudice Fall by Jane Austen Instructions: (No specified Independent Reading) Read the unabridged version, and write an original poem - minimum 30 lines - about the ideals, values, or concerns of the Bennets or the society in which they live. Due the first day of school in August. You will also write an AP style literary analysis Spring essay on Pride and Prejudice during first semester. Perelandra Fall by C.S. Lewis (No specified Independent Reading) Instructions: Read specified chapters weekly, prepare "Wisdom Chair" discussion points. Upon Spring completion, compose a rhetorical analysis Gilead style essay discussing Lewis' stylistic choices by Marilynn Robinson and their impact on the message. Texts will be provided. Texts will be provided. Assessment information will be explained in the spring. If you have any questions about AP Independent reading, email Mrs. Beck: [email protected].. -

Introducing CS Lewis

Volume 1 Issue 3 Article 7 January 1972 Introducing C.S. Lewis: Sincerity Personified Kathryn Lindskoog Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythpro Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Lindskoog, Kathryn (1972) "Introducing C.S. Lewis: Sincerity Personified," Mythcon Proceedings: Vol. 1 : Iss. 3 , Article 7. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythpro/vol1/iss3/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythcon Proceedings by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mythcon 51: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico • Postponed to: July 30 – August 2, 2021 Abstract An overview of C.S. Lewis’s life, primarily based on Surprised by Joy and Letters, covering the entire period from his birth to death with special emphasis on his education and conversion. Includes personal reminiscences of the author’s own meeting with him in 1956. This is the first chapter of Lindskoog’s biography of Lewis. Keywords Lewis, C.S.— Biography; Lewis, C.S.—Personal reminisences This article is available in Mythcon Proceedings: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythpro/vol1/iss3/7 Dnt:r<onacfnGLindskoog: Introducing C.S. Lewis:ml Sincerity ~ Personified l!ewfs= sfncer<ft:J! per<sont-i:ten by Kathryn Lindskoog "lie struck me as the most thoroughly converted for the distant green hills on the horizon. In contrast, man I ever met.• Walter Hooper they had some dazzling sandy summer days at the beach; C. -

Meet Beverley's New Narnia Carvings! Aslan the Lion Farsight the Eagle

Meet Beverley’s new Narnia carvings! 14 characters from The Chronicles of Narnia by CS Lewis are being carved in stone for St Mary’s Church. Over the summer you can see them up close before they are put high on the church walls. Every time you see a carving in the display, it will have a code word and symbol next to it. Copy those onto this sheet. Return the sheet to us to get a certificate and a badge, and you’ll also be entered into a lucky draw to win a prize! Your name: ______________________________________________________________ What is the code for each Narnia character? Younger quizzers can copy the symbol, older quizzers can copy the word. Aslan the lion Farsight the eagle Fledge the winged horse Ginger the cat Glenstorm the centaur Glimfeather the owl Jewel the unicorn Maugrim the wolf Mr Tumnus the faun Reepicheep the mouse Shift the ape Slinkey the fox The White Witch Trufflehunter the badger The carvings will be displayed in groups, changing every two weeks during the school holidays: • Display 1 6pm Friday 17th July – 4pm Thursday 30th July • Display 2 11am Friday 31st July – 4pm Thursday 13th August • Display 3 11am Friday 14th August – 4pm Thursday 27th August • Display 4 11am Friday 28th August – 4pm Thursday 10th September When you have seen them all you can: • put your completed sheet through the letterbox at the display (Streamers shop) • post it to St Mary’s Narnia Quiz, 2 Wheatsheaf Lane, Beverley, HU17 0HH, or • scan it and email it to: [email protected] Name of parent/guardian: _______________________________________________________ Phone no or email address: ______________________________________________________ Optional bonus activity We would love to see and exhibit your own artwork inspired by our Narnia carvings. -

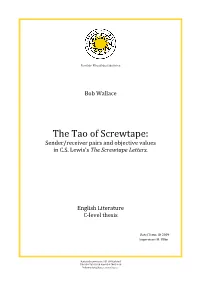

The Tao of Screwtape: Sender/Receiver Pairs and Objective Values in C.S

Estetisk- Filosofiska fakulteten Bob Wallace The Tao of Screwtape: Sender/receiver pairs and objective values in C.S. Lewis’s The Screwtape Letters. English Literature C-level thesis Date/Term: Ht 2009 Supervisor: M. Ullén Karlstads universitet 651 88 Karlstad Tfn 054-700 10 00 Fax 054-700 14 60 [email protected] www.kau.se Title: The Tao of Screwtape: An examination of sender/receiver pairs for awareness of and relationship to a doctrine of objective values in C.S. Lewis’s The Screwtape Letters. Author: Bob Wallace Eng C, HT 2009 Pages: 15 Abstract: The purpose of this essay is to identify the various sender/receiver pairs from C.S. Lewis’s novel The Screwtape Letters and, once identified, to examine these pairs within the context of the concept of a doctrine of universal values which is expressed in Lewis’s The Abolition of Man. For the sake of clarity and simplicity the essay begins with a definition of terms and concepts that will be used throughout, including basic terms used when discussing a communicative act: sender, receiver and message. I then explain the essays central concept which is taken from another one of Lewis’s works The Abolition of Man regarding a doctrine of objective value. The idea that a set of universal values exists is often central to secular writing and C.S Lewis, a Christian apologist, makes it clear that he believes that there exists an ethical way of living that is common to all men, Christian and non- Christian alike. He dubs this set of basic morals the Tao. -

Myth in CS Lewis's Perelandra

Walls 1 A Hierarchy of Love: Myth in C.S. Lewis’s Perelandra A Thesis Submitted to The Faculty of the School of Communication In Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts in English by Joseph Robert Walls May 2012 Walls 2 Liberty University School of Communication Master of Arts in English _______________________________________________________________________ Thesis Chair Date Dr. Branson Woodard, D.A. _______________________________________________________________________ First Reader Date Dr. Carl Curtis, Ph.D. _______________________________________________________________________ Second Reader Date Dr. Mary Elizabeth Davis, Ph.D. Walls 3 For Alyson Your continual encouragement, support, and empathy are invaluable to me. Walls 4 Contents Introduction......................................................................................................................................5 Chapter 1: Understanding Symbol, Myth, and Allegory in Perelandra........................................11 Chapter 2: Myth and Sacramentalism Through Character ............................................................32 Chapter 3: On Depictions of Evil...................................................................................................59 Chapter 4: Mythical Interaction with Landscape...........................................................................74 A Conclusion Transposed..............................................................................................................91 Works Cited ...................................................................................................................................94 -

Irrigating Deserts with Moral Imagination by PETER J

Copyright © 2004 The Center for Christian Ethics at Baylor University 21 Irrigating Deserts with Moral Imagination BY PETER J. SCHAKEL Without the imagination, morality remains ethics—ab- stract reflections on principles that we might never put into practice. With imagination, we connect principles to everyday life and relate to the injustices faced by oth- ers as we picture what they experience and feel. Stories feed the moral imagination, C. S. Lewis reminds us, and nurture the judgments of our heart. xcept for salvation, imagination is the most important matter in the thought and life of C. S. Lewis. He believed the imagination was a Ecrucial contributor to the moral life, as well as an important source of pleasure in life and a vital evangelistic tool (much of Lewis’s effectiveness as an apologist lies in his ability to illuminate difficult concepts through apt analogies). Without the imagination, morality remains ethics—abstract re- flections on principles that we might never put into practice. The imagina- tion enables us to connect abstract principles to everyday life, and to relate to the injustices faced by others as we imagine what they experience and feel. Though Lewis did not use the term “moral imagination” and recent writers on moral imagination rarely cite or draw upon him, he presented a clear, accessible, and powerful delineation of the concept long before it be- came popularized in the 1980s and 1990s.1 The term originated with the Irish philosopher and political thinker Edmund Burke (1729-1797), in his Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790), a book Lewis mentions in a letter to his father as the best introduc- tion to the medieval idea of love.2 The French Revolution, Burke asserts, 22 Inklings of Glory put an end to the system of opinion and sentiment that had given Europe its distinct character. -

A CS Lewis Related Cumulative Index of <I>Mythlore</I>

Volume 22 Number 2 Article 10 1998 A C.S. Lewis Related Cumulative Index of Mythlore, Issues 1-84 Glen GoodKnight Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation GoodKnight, Glen (1998) "A C.S. Lewis Related Cumulative Index of Mythlore, Issues 1-84," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 22 : No. 2 , Article 10. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol22/iss2/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Author and subject index to articles, reviews, and letters in Mythlore 1–84. Additional Keywords Lewis, C.S.—Bibliography; Mythlore—Indexes This article is available in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol22/iss2/10 MYTHLORE I s s u e 8 4 Sum m er 1998 P a g e 5 9 A C.S. -

ABSTRACT C.S. Lewis and the Conversion of the Aeneas Story In

ABSTRACT C.S. Lewis and the Conversion of the Aeneas Story in the Ransom Trilogy Katherine Grace Hornell Directors: Phillip J. Donnelly, Ph.D. and Alan Jacobs, Ph.D. Many readers of C. S. Lewis’s writing consider his science fiction trilogy an odd divergence from his expected repertoire. Though Lewis’ "Ransom Trilogy" proves distinctive among his works, the books grow from the same deep roots in classical and medieval literary traditions that inform his other writings. Drawing from Virgil, Dante, and Arthurian legend to structure his narrative, Lewis unites ancient myth and modern fiction in order to illumine Classical stories with Christian faith. This thesis considers how Lewis’s science fiction draws on the features of secondary epic and its attendant meanings that appear in the Aeneid and in Arthurian stories. Ultimately, Lewis models how contemporary writers can make old stories live anew. APPROVED BY DIRECTOR OF HONORS THESIS: __________________________________________________ Dr. Phillip J. Donnelly, Department of Great Texts APPROVED BY THE HONORS PROGRAM: ________________________________________________ Dr. Elizabeth Corey, Director DATE: __________________ C.S. LEWIS AND THE CONVERSION OF THE AENEAS STORY IN THE RANSOM TRILOGY A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Baylor University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Honors Program By Katherine Grace Hornell Waco, Texas August 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments………………………………………………………....…………..iii Introduction…………………………………………………………………………….1 Chapter One: Out of the Silent Planet………………………………………………….4 Chapter Two: Perelandra……………………………………………………………..22 Chapter Three: That Hideous Strength………………………………………………..43 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………….62 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………..65 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my sincere thanks both to Dr. Alan Jacobs and to Dr. Phillip J. -

Visions/Versions of the Medieval in C.S. Lewis's the Chronicles of Narnia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Boise State University - ScholarWorks VISIONS/VERSIONS OF THE MEDIEVAL IN C.S. LEWIS’S THE CHRONICLES OF NARNIA by Heather Herrick Jennings A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English, Literature Boise State University Summer 2009 © 2009 Heather Herrick Jennings ALL RIGHTS RESERVED v TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................... vii CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 1 Lewis and the Middle Ages ............................................................................ 6 The Discarded Image ...................................................................................... 8 A Medieval Atmosphere ................................................................................. 10 CHAPTER TWO: THE HEAVENS OF NARNIA .................................................... 13 The Stars above Narnia ................................................................................... 15 The Narnian Planets ........................................................................................ 18 The Influence of the Planets ........................................................................... 19 The Moon and Fortune in Narnia ................................................................... 22 An Inside-Out Universe ................................................................................. -

The Last Battle. (First Published 1956) by C.S

The Last Battle C. S. L e w i s Samizdat The Last Battle. (first published 1956) by C.S. Lewis (1895-1963) Edition used as base for this ebook: New York: Macmillan, 1956 Source: Project Gutenberg Canada, Ebook #1157 Ebook text was produced by Al Haines Warning : this document is for free distribution only. Ebook Samizdat 2017 (public domain under Canadian copyright law) Disclaimer This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost. Copyright laws in your country also govern what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in a constant state of flux. If you are outside Canada, check the laws of your country before down- loading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or creating derivative works based on this Samizdat Ebook. Samizdat makes no claims regarding the copyright status of any work in any country outside Canada. Table Of Contents CHAPTER I By Caldron Pool 1 CHAPTER II The Rashness of the King 8 CHAPTER III The Ape in Its Glory 15 CHAPTER IV What Happened that Night 22 CHAPTER V How Help Came to the King 28 CHAPTER VI A Good Night's Work 35 CHAPTER VII Mainly About Dwarfs 42 CHAPTER VIII What News the Eagle Brought 50 CHAPTER IX The Great Meeting on Stable Hill 57 The Last Battle iii CHAPTER X Who Will Go into the Stable? 64 CHAPTER XI The Pace Quickens 71 CHAPTER XII Through the Stable Door 78 CHAPTER XIII How the Dwarfs Refused to be Taken In 85 CHAPTER XIV Night Falls on Narnia 93 CHAPTER XV Further Up and Further In 100 CHAPTER XVI Farewell to Shadow-Lands 107 CHAPTER I By Caldron Pool n the last days of Narnia, far up to the west beyond Lantern Waste and close beside the great waterfall, there lived an Ape. -

The Voyage of the Dawn Treader: a Study of Eustace Scrubb´S Character

International Journal on Studies in English Language and Literature (IJSELL) Volume 9, Issue 4, April 2021, PP 39-46 ISSN 2347-3126 (Print) & ISSN 2347-3134 (Online) https://doi.org/10.20431/2347-3134.0904004 www.arcjournals.org The Chronicles of Narnia - The Voyage of the Dawn Treader: A Study of Eustace Scrubb´s Character Sara Torres Servín* Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, South Korea *Corresponding Authors:Sara Torres Servín,Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, South Korea Abstract:The Voyage of the Dawn Treader is a story in which the children who are the main characters go through painful processes that seek to transform them into better human beings. Such is the case of Eustace Clarence Scrubb, an English boy of around eight years of age. He is hopelessly doomed to his own self destruction if drastic measures are not taken to help him come out of his self-absorption and intrinsic bad personal traits. This boy is the by-product of an education given him by progressive parents and a progressive school, both of which see nothing wrong with the character, attitudes and behavior of this irritating boy. The worst thing about Eustace’s character, however, is the fact that he does not and cannot see himself as others view him, as the insufferable human being that he is. Only when he is going through the agony of being a horrific monster does he come to his senses and starts seeing himself as the monster he really is inside and outside. It is then that he realizes that he is the problem that he would accuse everybody of being.