The Washington Post January 28, 1997, Tuesday

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

King Honored Today in Fu Nera H Memorial Grieving, Widow East

1 0 0,000 EXPECTKD »1 T u e s d a y King honored today MICHIGAN STATI in fu nera h memorial UNIVERSITY ATLANTA, Ga. (AP)--The church where King's sons, Martin Luther King III, 10, East Lansing, Michigan April 9,1968 10c Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. preached and Dexter King, 8. Vol. 60 Number 152 a doctrine of defiance that rang from Dr. King also had two daughters, Yolan shore to shore opened its doors in funeral da, 12, and Bernice, 5. Dr. Gloster indicated silence Monday to receive the body of the that Spelman College, an all-female m a rt y re d N e g r o idol. college whose campus adjoins the More Tens of thousands of mourners, black house campus, would grant scholarships and while and from every social level, to Dr. King’s daughters. The chapel at b i d Spelman College is where Dr. King lay in N . Viets accept arrived in the city of his birth for the fun eral. Services will be at 10:30 a.m. today repose. at the Ebenezer Baptist Church where Dr. Among the dignitaries who have said King, 39. was co-pastor with his father they will attend the funeral are Sen. Robert the past eight years. Kennedy and Gov. Nelson Rockefeller Other thousands filed past his bier in of New York, Undersecretary-General advisers meet at Cam p David a sorrowing procession of tribute that Ralph Bunche of the United Nations, New wound endlessly toward a quiet campus York M a y o r John V. -

The Atlanta Journal and Constitution March 29, 1998, Sunday, ALL EDITIONS

The Atlanta Journal and Constitution March 29, 1998, Sunday, ALL EDITIONS New 'leads' in King case invariably go nowhere David J. Garrow PERSPECTIVE; Pgs. C1, C2. LENGTH: 1775 words Do the never-ending claims of revelations concerning the April 4, 1968, assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. leave you a bit confused? What should we make of the assertion that U.S. Army military intelligence --- and President Lyndon B. Johnson --- were somehow involved? Why is Jack Ruby, who killed Lee Harvey Oswald two days after Oswald assassinated President John F. Kennedy in 1963, now turning up in the King assassination story? And what about former FBI agent Donald Wilson's claim that notes he pilfered from James Earl Ray's automobile and then concealed for 30 years contain a significant telephone number. Maybe you saw the ABC "Turning Point" documentary with Forrest Sawyer that demolished the Army intelligence allegations. Or perhaps you watched CBS' "48 Hours" broadcast with Dan Rather last week, which refuted the claims that some fictional character named "Raoul," acting in cahoots with Ruby, was responsible for both the Kennedy and the King assassinations. Don't worry. All of this actually is easier to follow than you may think, so long as you keep a relatively simply score card. All you need to do is remember the "three R's" --- Ray, "Raoul" and Ruby --- and also distinguish the "three P's" --- William F. Pepper, Gerald Posner and Marc Perrusquia. Ray you know. Now 70 years old and seriously ill, Ray pleaded guilty to King's slaying in 1969 but has spent the past 29 years trying to withdraw his plea. -

Martin Luther King Jr

Martin Luther King Jr. Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist who The Reverend became the most visible spokesperson and leader in the American civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968. King Martin Luther King Jr. advanced civil rights through nonviolence and civil disobedience, inspired by his Christian beliefs and the nonviolent activism of Mahatma Gandhi. He was the son of early civil rights activist Martin Luther King Sr. King participated in and led marches for blacks' right to vote, desegregation, labor rights, and other basic civil rights.[1] King led the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott and later became the first president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). As president of the SCLC, he led the unsuccessful Albany Movement in Albany, Georgia, and helped organize some of the nonviolent 1963 protests in Birmingham, Alabama. King helped organize the 1963 March on Washington, where he delivered his famous "I Have a Dream" speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. The SCLC put into practice the tactics of nonviolent protest with some success by strategically choosing the methods and places in which protests were carried out. There were several dramatic stand-offs with segregationist authorities, who sometimes turned violent.[2] FBI King in 1964 Director J. Edgar Hoover considered King a radical and made him an 1st President of the Southern Christian object of the FBI's COINTELPRO from 1963, forward. FBI agents investigated him for possible communist ties, recorded his extramarital Leadership Conference affairs and reported on them to government officials, and, in 1964, In office mailed King a threatening anonymous letter, which he interpreted as an attempt to make him commit suicide.[3] January 10, 1957 – April 4, 1968 On October 14, 1964, King won the Nobel Peace Prize for combating Preceded by Position established racial inequality through nonviolent resistance. -

Triumphant in Death James Earl Ray Is Laughing All the Way to Hell, Thanks to the King Family's Preposterous Belief That He Didn't Kill Martin Luther King Jr

triumphant in death James Earl Ray is laughing all the way to hell, thanks to the King family's preposterous belief that he didn't kill Martin Luther King Jr. http://www.salon.com/news/1998/04/28news.html BY DAVID J. GARROW | ATLANTA -- Very few people mourned the death last Thursday of James Earl Ray, the assassin of Martin Luther King Jr. Ray's brother Jerry, who for years worked for convicted church-bomber and professional anti-Semite J.B. Stoner, was one of the few. But Jerry had reasons to be thankful, too. His brother had never implicated him -- or their other brother John -- in any discussions or arrangements that preceded King's April 4, 1968, murder. What's more, James Earl's notoriety had allowed Jerry to garner considerable public attention as his imprisoned brother's primary spokesman. Rarely did any of the eager journalists raise the matter of Jerry's long, intimate relationship with the once-infamous Stoner. But those who seemed to mourn Ray's death even more than Jerry were the widow and children of King himself. Coretta Scott King asserted that her family was "deeply saddened" by Ray's death, and proclaimed that it was "a tragedy not only for Mr. Ray and his family, but also for the entire nation." Readers who recalled the awkwardly staged 1997 scene in which Dexter Scott King, King's younger son, shook Ray's very trigger hand and proclaimed the King family's belief in Ray's complete innocence should not have been shocked by Coretta King's peculiar expression of grief. -

![I Have a [Fair Use] Dream”: Historic Copyrighted Works and the Recognition of Meaningful Rights for the Public](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4774/i-have-a-fair-use-dream-historic-copyrighted-works-and-the-recognition-of-meaningful-rights-for-the-public-1554774.webp)

I Have a [Fair Use] Dream”: Historic Copyrighted Works and the Recognition of Meaningful Rights for the Public

Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal Volume 25 Volume XXV Number 4 Volume XXV Book 4 Article 2 2015 “I Have a [Fair Use] Dream”: Historic Copyrighted Works and the Recognition of Meaningful Rights for the Public Arlen W. Langvardt Kelley School of Business, Indiana University Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Arlen W. Langvardt, “I Have a [Fair Use] Dream”: Historic Copyrighted Works and the Recognition of Meaningful Rights for the Public, 25 Fordham Intell. Prop. Media & Ent. L.J. 939 (2015). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj/vol25/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “I Have a [Fair Use] Dream”: Historic Copyrighted Works and the Recognition of Meaningful Rights for the Public Cover Page Footnote The author acknowledges the helpful research assistance provided by Paul Lewellyn and Daniel Schiff. This article is available in Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj/vol25/iss4/2 “I Have a [Fair Use] Dream”: Historic Copyrighted Works and the Recognition of Meaningful Rights for the Public Arlen W. Langvardt* Dr. Martin Luther King wrote and delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech more than fifty years ago. -

A Critical Discourse Analysis of Interracial Marriages in Television Sitcoms

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2014 Drawing the Primetime Color Line: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Interracial Marriages in Television Sitcoms Jodi Lynn Rightler-McDaniels University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, and the Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons Recommended Citation Rightler-McDaniels, Jodi Lynn, "Drawing the Primetime Color Line: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Interracial Marriages in Television Sitcoms. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2014. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/2725 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Jodi Lynn Rightler-McDaniels entitled "Drawing the Primetime Color Line: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Interracial Marriages in Television Sitcoms." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Communication and Information. Catherine A. Luther, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Elizabeth Hendrickson, Lori Amber Roessner, Barbara Thayer-Bacon Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. -

Orbridge — Educational Travel Programs for Small Groups

For details or to reserve: wm.orbridge.com (866) 639-0079 APRIL 10, 2021 – APRIL 14, 2021 POST-TOUR: APRIL 14, 2021 — APRIL 16, 2021 CIVIL RIGHTS—A JOURNEY TO FREEDOM The Alabama cities of Montgomery, Birmingham, and Selma birthed the national leadership of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s and 1960s, when tens of thousands of people came together to advance the cause of justice against remarkable odds and fierce resistance. In partnership with the non-profit Alabama Civil Rights Tourism Association and in support of local businesses and communities, Orbridge invites you to experience the people, places, and events igniting change and defining a pivotal period for America that continues today. Dive deeper beyond history's headlines to the newsmakers, learning from actual foot soldiers of the struggle whose vivid and compelling stories bring a history of unforgettable tragedy and irrepressible triumph to life. Dear Alumni and Friends, Join us for an intimate and essential opportunity to explore the Deep South with an informative program that highlights America’s civil rights movement in Alabama. Historically, perhaps no other state has played as vital a role, where a fourth of the official U.S. Civil Rights Trail landmarks are located. On this five-day journey, discover sites that advanced social justice and shifted the course of history. Stand in the pulpit at Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church where Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. preached, walk over the Edmund Pettus Bridge where law enforcement clashed with voting rights marchers, and gather with our group at Kelly Ingram Park as 1,000 or so students did in the 1963 Children’s Crusade. -

The Orchestrated Assassination of Martin King Marcus Kline

The Orchestrated Assassination of Martin King Marcus Kline *Courtesy of Frontline Magazine The assassination of Martin King was designed, orchestrated and covered-up by the United Snakkkes government. Is this the ravings of a madman consumed by conspiracy theories? Well, according to a Memphis jury's verdict on December 8, 1999, in the wrongful death lawsuit of the King family versus Loyd Jowers "and other unknown co-conspirators," (the majority of this article is based on this trial) Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated by a conspiracy that included agencies of his own government. Almost 38 years after King's murder at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis on April 4, 1968, a court extended the circle of responsibility for the assassination beyond the late scapegoat James Earl Ray to the United Snakkkes government. On April 4, 1967, Riverside Church, New York City, Martin Luther King, Jr. condemns the Vietnam War and identifies the U. S. government as "the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today." The Riverside Church speech provokes intense hostility in the White House and FBI. Hatred and fear of King deepens in response to King's plan to hold the Poor People's Campaign in Washington, D. C, with an intent to shut down the nation's capital in the spring of 1968.1 Judge Joe Brown, who had presided over two years of hearings on the rifle, testified that "67% of the bullets from my tests did not match the Ray rifle." He added that the unfired bullets found wrapped with it in a blanket were metallurgically different from the bullet taken from King's body, and therefore were from a different lot of ammunition. -

Martin Luther King Speeches on Unions and Labor

What Martin Luther King Said about unionS, uneMpLoyMent and econoMic JuStice QuotationS froM King’S SpeecheS to trade unionS the Martin Luther King Jr. center for nonvioLent SociaL change All quotations copyright © 1963 by Martin Luther King Jr. Copyright © renewed 1986 by Coretta Scott King, Dexter King, Martin Luther King III, Yolanda King and Bernice King. All Rights Reserved. The speeches in which these quotations appear can be found in All Labor Has Dignity, edited and with an introduction by Michael Honey, Beacon Press, 2011. The labor movemenT was The principAL force that transformed the misery and despair into hope and progress. Out of its bold struggles, economic and social reform gave birth to unemployment insurance, old- age pensions, government relief for the destitute, and, above all, new wage vaLue levels that meant not mere survival but a tolerable life. The captains of industry did not lead this transformation; they resisted it until they were of overcome. When in the thirties the wave of union organization crested over the nation, it carried to secure shores not only itself but the whole society. unionS Civilization began to grow in the economic life of man, and a decent life with a sense of security and dignity became a reality rather than a distant dream. It is a mark of our intellectual backwardness that these monumental achievements of labor are still only dimly seen, and in all too many circles the term “union” is still synonymous with self-seeking, power hunger, racketeering, and cynical coercion. There have been and still are wrongs in the trade union movement, but its share of credit for triumphant accomplishments is substantially denied in the historical treatment of the nation’s progress. -

Dr. King's Son M Ets Ray, and Then Says He's Nnocent

KING from Al Dr. King the previous year and was sentenced to 99 years in prison. He recanted three days later, claiming that his lawyer had coerced him. The judge died while considering his request for a trial. Ray has been trying to get a trial ever since. William Pepper, Ray's current at- torney and a former associate of Dr. King, said Ray was a pawn of gov- ernment forces who manipulated him and conspired with organized crime to murder Dr. King. A Tennessee appeals court is con- ; sidering whether to grant a request to allow experts hired by Pepper to test the rifle and remnants of the A ociated Press / EARL WARREN fatal bullet with a sophisticated electron microscope. Earlier tests, After meeting in prison, Dexter King says goo -bye to James Earl all conducted by government ex- Ray. He spoke yesterday with the man convic ed of killing his father. perts, were inconclusive. While yesterday's meeting was the first between Ray and a member of Dr. King's family, a number of Dr. King's son m ets Ray, the civil rights leader's associates have long championed Ray's inno- cence. and then says he's nnocent Pepper and Ralph Abernathy, who succeeded Dr. King as president of the Southern Christian Leadership By Eric Harrison to a Nashvi le prison hospital to ask: LOS ANGELES TIMES Conference, first met with Ray in "Did you 11 my father?" 1978. After subsequent investigatory ATLANTA — It was, as Dexter "No, no,' a frail Ray said. "I work, Pepper said he became con- King kept saying, an "awkward" mo- didn't." vinced of Ray's innocence. -

William F. Pepper

This document is online at: ratical.org/ratville/JFK/WFP020403.html Editor’s note: the following is a hypertext transcript of William Pepper speaking on the release of his new book, An Act of State - The Execution of Martin Luther King (Verso, 2003). Deepest thanks go to friends Penny Schoner and Maria Gilardin (tucradio.org) each of whom made and shared audio recordings from which this transcript was created. Dr. Pepper was introduced by Amanda Davidson. Dr. William F. Pepper practices international human rights law from London, convenes a seminar on international human rights at Oxford University, has © Flip Schulke/CORBIS represented governments and heads of state, and Martin Luther King and Coretta appeared as an expert on international law issues. Scott King leading the March Against Fear in rural Mississippi, June 1966. William F. Pepper - An Act of State The Execution of Martin Luther King Talk given at Modern Times Bookstore, San Francisco, CA 4 February 2003 Links last checked and made current: 14 July 2019 Tonight we have a very special author whose book, An Act of State: The Execution of Martin Luther King, Jr., has just been published by Verso. William Pepper is an English barrister and an American lawyer. He convenes a seminar on International Human Rights at Oxford University. He maintains a practice in the U.S. and the U.K. He is author of three other books and numerous articles. This book is the result of a quarter-century of an investigation. I will let Dr. Pepper give you more information. Let’s give a warm welcome to William Pepper. -

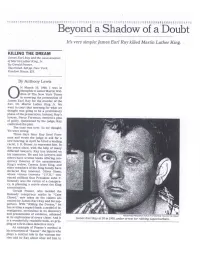

Beyond a Shadow of a Doubt

;; "1 ! "! IWO k 7 V31; 411,7, ZT,": t..Y t!'*1 I‘ /1 .0 91 1.4 S!!4 It Beyond a Shadow of a Doubt It's very simple: James Earl Ray killed Martin Luther King. KILLING THE DREAM James Earl Ray and the Assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. By Gerald Posner. Illustrated. 446 pp. New York: Random House. $25. By Anthony Lewis N March 10, 1969, I was in Memphis to assist Martin Wal- dron of The New York Times in covering the prosecution of 0James Earl Ray for the murder of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. We went to court that morning for what we thought was going to be a preliminary phase of the prosecution. Instead, Ray's lawyer, Percy Foreman, entered a plea of guilty. Questioned by the judge, Ray confirmed the plea. The case was over. So we thought. We were wrong. Three days later Ray fired Fore- man and wrote the judge to ask for a new hearing; in April he hired a leading racist, J. B. Stoner, to represent him. In the years since, with the help of many different lawyers, Ray has insisted on his innocence. He and his lawyers and others have written books offering con- spiracy theories of the assassination. King's widow, Coretta Scott King, and other members of the King family have declared Ray innocent. Oliver Stone, whose vicious travesty "J.F.K." con- vinced millions that President John F. Kennedy was the victim of a conspira- cy, is planning a movie about the King assassination.