A Critical Discourse Analysis of Interracial Marriages in Television Sitcoms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

31, 1-January Heritage Newsletter 2019

Heritage Newsletter California African-American Genealogical Society January 2019 Volume 31, Number 1 Ten Issues Published Annually CHARLOTTA SPEARS BASS ISSN 1083-8937 She was a feminist, an activist, an educator, the first California African American Genealogical Society African-American woman to own and operate a P.O. Box 8442 newspaper in the United States (1912-1951), the first Los Angeles, CA 90008-0442 African-American woman to be a jury member in the Los Angeles County Court and the first African- General Membership Meetings American woman to be nominated for U.S. Vice Third Saturday monthly,10:00A.M. (dark July & August) President (Progressive Party). Born Charlotta Amanda Spears in Sumter, South Carolina in 1874, Mayme Clayton Library and Museum (MCLM) she moved to Rhode Island where she worked for the 4130 Overland Ave., Culver City, CA 90230-3734 Providence Watchman newspaper for ten years, and (Old Culver City Courthouse across from VA building) in 1910 moved to Los Angeles where she sold subscriptions for the Eagle, a black newspaper 2019 Board of Directors founded by John Neimore in 1879. The Eagle, a Elected Officers twenty-page weekly publication with a staff of 12 and Cartelia Marie Bryant– President circulation of 60,000, was the largest African- Ron Batiste– First Vice President American newspaper on the West Coast by 1925. Norma Bates – Second Vice President/Membership Ronald Fairley – Corresponding Secretary When Neimore became ill, he entrusted the operation Christina Ashe– Recording Secretary of the Eagle to Spears, and upon his death, she Shirley Hurt – Treasurer subsequently bought the newspaper for fifty dollars in Charles Hurt – Parliamentarian an auction and became the owner. -

Race and Membership in American History: the Eugenics Movement

Race and Membership in American History: The Eugenics Movement Facing History and Ourselves National Foundation, Inc. Brookline, Massachusetts Eugenicstextfinal.qxp 11/6/2006 10:05 AM Page 2 For permission to reproduce the following photographs, posters, and charts in this book, grateful acknowledgement is made to the following: Cover: “Mixed Types of Uncivilized Peoples” from Truman State University. (Image #1028 from Cold Spring Harbor Eugenics Archive, http://www.eugenics archive.org/eugenics/). Fitter Family Contest winners, Kansas State Fair, from American Philosophical Society (image #94 at http://www.amphilsoc.org/ library/guides/eugenics.htm). Ellis Island image from the Library of Congress. Petrus Camper’s illustration of “facial angles” from The Works of the Late Professor Camper by Thomas Cogan, M.D., London: Dilly, 1794. Inside: p. 45: The Works of the Late Professor Camper by Thomas Cogan, M.D., London: Dilly, 1794. 51: “Observations on the Size of the Brain in Various Races and Families of Man” by Samuel Morton. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences, vol. 4, 1849. 74: The American Philosophical Society. 77: Heredity in Relation to Eugenics, Charles Davenport. New York: Henry Holt &Co., 1911. 99: Special Collections and Preservation Division, Chicago Public Library. 116: The Missouri Historical Society. 119: The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, 1882; John Singer Sargent, American (1856-1925). Oil on canvas; 87 3/8 x 87 5/8 in. (221.9 x 222.6 cm.). Gift of Mary Louisa Boit, Julia Overing Boit, Jane Hubbard Boit, and Florence D. Boit in memory of their father, Edward Darley Boit, 19.124. -

The Converging Martyrdom of Malcolm and Martin

This document is online at: http://ratical.org/ratville/JFK/Unspeakable/ConvMartyrdom.html This is a hypertext representation of Jim Douglass’ lecture with his original footnotes as well as some additions. Hyperlinks and additional notes by David Ratcliffe with the assistance and approval of Jim Douglass. In September 2005, James Douglass accepted an invitation from the president of Princeton Theological Seminary on behalf of the Council on Black Concerns to deliver their annual Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Lecture on March 29, 2006. Previous lecturers included James H. Cone, Katie Geneva Cannon, and Michael Dyson. The Converging Martyrdom of Malcolm and Martin Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Lecture Princeton Theological Seminary by James W. Douglass March 29, 2006 Copyright © 2006, 2013 James W. Douglass Salaam aleikum. Shalom. Peace be with you. When Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated in the spring of 1968, I was teaching a religion course at the University of Hawaii called “The Theology of Peace.” Several students were moved by King’s death and his resistance to the Vietnam War to burn their draft cards, making them liable to years in prison. I joined their anti-war group, the Hawaii Resistance. A month later, we sat in front of a convoy of trucks taking the members of the Hawaii National Guard to Oahu’s Jungle Warfare Training Center, on their way to the jungles of Vietnam. I went to jail for two weeks – the beginning of the end of my academic career. Members of the Hawaii Resistance served from six months to two years in prison for their draft resistance, or wound up going into exile in Sweden or Canada. -

'Nothing but the Truth': Genre, Gender and Knowledge in the US

‘Nothing but the Truth’: Genre, Gender and Knowledge in the US Television Crime Drama 2005-2010 Hannah Ellison Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) University of East Anglia School of Film, Television and Media Studies Submitted January 2014 ©This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis, nor any information derived therefrom, may be published without the author's prior, written consent. 2 | Page Hannah Ellison Abstract Over the five year period 2005-2010 the crime drama became one of the most produced genres on American prime-time television and also one of the most routinely ignored academically. This particular cyclical genre influx was notable for the resurgence and reformulating of the amateur sleuth; this time remerging as the gifted police consultant, a figure capable of insights that the police could not manage. I term these new shows ‘consultant procedurals’. Consequently, the genre moved away from dealing with the ills of society and instead focused on the mystery of crime. Refocusing the genre gave rise to new issues. Questions are raised about how knowledge is gained and who has the right to it. With the individual consultant spearheading criminal investigation, without official standing, the genre is re-inflected with issues around legitimacy and power. The genre also reengages with age-old questions about the role gender plays in the performance of investigation. With the aim of answering these questions one of the jobs of this thesis is to find a way of analysing genre that accounts for both its larger cyclical, shifting nature and its simultaneously rigid construction of particular conventions. -

19 Lc 119 0136 Hr

19 LC 119 0136 House Resolution 160 By: Representatives McLeod of the 105th, Hutchinson of the 107th, Clark of the 108th, Mitchell of the 88th, Thomas of the 56th, and others A RESOLUTION 1 Commending the many contributions Caribbean Americans have made to the State of 2 Georgia and the United States and recognizing March 14, 2019, as Caribbean American Day 3 at the state capitol; and for other purposes. 4 WHEREAS, many people of Caribbean American heritage have made political and military 5 contributions to weave the fabric of the United Sates since its inception, including Senator 6 Kamala Harris, the first woman of Caribbean heritage and second black woman in the 7 nation's history to serve in Congress' upper chamber; Alexander Hamilton, who was born in 8 the Caribbean and was a founding father and Chief Staff Aide to George Washington; 9 Crispus Attucks, the first person to give his life for the freedom of the United States; 10 Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm, a presidential candidate and the first black woman 11 elected to Congress; General Colin Powell, the 65th United States Secretary of State and 12 Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff during the Persian Gulf War; United States 13 Representative Yvette Clark, who accompanied President Obama to Jamaica; Eric Holder, 14 the Attorney General under President Obama's administration; Sharon Lawson, the award- 15 winning journalist and anchor of Good Day Atlanta on FOX 5; Uldeen Lee, one of the first 16 women of color to receive a Bachelor's of Science degree in Computer Science from -

The N-Word : Comprehending the Complexity of Stratification in American Community Settings Anne V

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2009 The N-word : comprehending the complexity of stratification in American community settings Anne V. Benfield Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Race and Ethnicity Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Benfield, Anne V., "The -wN ord : comprehending the complexity of stratification in American community settings" (2009). Honors Theses. 1433. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/1433 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The N-Word: Comprehending the Complexity of Stratification in American Community Settings By Anne V. Benfield * * * * * * * * * Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of Sociology UNION COLLEGE June, 2009 Table of Contents Abstract 3 Introduction 4 Chapter One: Literature Review Etymology 7 Early Uses 8 Fluidity in the Twentieth Century 11 The Commercialization of Nigger 12 The Millennium 15 Race as a Determinant 17 Gender Binary 19 Class Stratification and the Talented Tenth 23 Generational Difference 25 Chapter Two: Methodology Sociological Theories 29 W.E.B DuBois’ “Double-Consciousness” 34 Qualitative Research Instrument: Focus Groups 38 Chapter Three: Results and Discussion Demographics 42 Generational Difference 43 Class Stratification and the Talented Tenth 47 Gender Binary 51 Race as a Determinant 55 The Ambiguity of Nigger vs. -

Movie Catalog Movie

AVENGERS BY THE NUMBERS On-Board Inside front cover EVERYTHING GAME OF THRONES MOVIE CATALOG Pages 36-38 © 2019 Marvel © 2019 Universal City Studios Productions LLLP. All Rights Reserved. © 2019 Paramount Pictures © 2019 Warner Bros. Ent. All rights reserved. © 2019 RJD Filmworks, Inc. All Rights Reserved. © Lions Gate Entertainment, Inc. STX Entertainment 2019 © © Amazon Studios © 2019 Disney Enterprises, inc. © 2019 STX Entertainment 2019 © © Lions Gate Entertainment, Inc. © 2019 Warner Bros. Ent. All rights reserved. July/August 2019 | 1.877.660.7245 | swank.com/on-board-movies H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H ExperienceH H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H HTHE H ADVENTURESH H H H H H H H of the AVENGERS H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H © 2019 Marvel © 2019 Marvel © 2019 Marvel © 2019 Universal City Studios Productions LLLP. All Rights Reserved. © 2019 Marvel H HH H H H H H HH HH H HH HH H 2008H H H H H H HH H H H H 2008H H H H H H H H H H2010 H H H H H H H H H2011 H H H H H H H H H2011 H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H © 2019 Marvel © 2019 Marvel © 2019 Marvel © 2019 Marvel © 2019 Marvel © 2019 Marvel © 2019 Marvel H H H H H2012 H H H H H H H H H2013 H H H H H H H H H2013 H H H H H H H H H2014 H H H H H H H H H 2014H H H H H H H H H 2015H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H H © 2019 Marvel © 2019 Marvel © 2019 Marvel © 2019 Marvel © 2019 Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. -

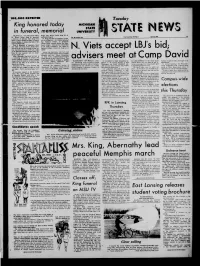

King Honored Today in Fu Nera H Memorial Grieving, Widow East

1 0 0,000 EXPECTKD »1 T u e s d a y King honored today MICHIGAN STATI in fu nera h memorial UNIVERSITY ATLANTA, Ga. (AP)--The church where King's sons, Martin Luther King III, 10, East Lansing, Michigan April 9,1968 10c Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. preached and Dexter King, 8. Vol. 60 Number 152 a doctrine of defiance that rang from Dr. King also had two daughters, Yolan shore to shore opened its doors in funeral da, 12, and Bernice, 5. Dr. Gloster indicated silence Monday to receive the body of the that Spelman College, an all-female m a rt y re d N e g r o idol. college whose campus adjoins the More Tens of thousands of mourners, black house campus, would grant scholarships and while and from every social level, to Dr. King’s daughters. The chapel at b i d Spelman College is where Dr. King lay in N . Viets accept arrived in the city of his birth for the fun eral. Services will be at 10:30 a.m. today repose. at the Ebenezer Baptist Church where Dr. Among the dignitaries who have said King, 39. was co-pastor with his father they will attend the funeral are Sen. Robert the past eight years. Kennedy and Gov. Nelson Rockefeller Other thousands filed past his bier in of New York, Undersecretary-General advisers meet at Cam p David a sorrowing procession of tribute that Ralph Bunche of the United Nations, New wound endlessly toward a quiet campus York M a y o r John V. -

January 19 2015, Martin Luther King, Jr

OMNI MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR. DAY, JANUARY 19, 2015. http://jamesrichardbennett.blogspot.com/2015/01/martin-luther-king-jr- day-2015.html Compiled by Dick Bennett for a Culture of Peace and Justice (Revised January 22) OMNI’s newsletters offer all a free storehouse of information and arguments for discussions, talks, and writings—letters to newspapers, columns, magazine articles. What’s at stake: Who was Martin Luther King, Jr.? The Incomplete Legacy: An introduction to this newsletter In 1963, Martin Luther King, Jr., stood before Lincoln’s statue in Washington, D.C. to say to the tens of millions of people watching there and on television, “I have a dream,” and to call upon the citizens of the United States to heed its ideals of freedom, equality, and brotherhood. He did not challenge the existing social order of the nation; rather his crusade was against an aberrant order, the “Jim Crow” system of discrimination of the old South. By 1968 King’s vision was darker. He had taken up the anti-war cause, decrying his country’s war in Vietnam as approaching genocide, and condemning U. S. militarism and imperialism. And in 1968 King was preparing an assault on the class structure of the nation in defense of the nation’s poor but was murdered before he could begin his most radical campaign. King’s work against war and poverty left undone has been overshadowed by his success as a civil rights leader—his complete vision obscured. The goal of all peace and justice groups should be to uncover the whole legacy of this historic proponent of racial equality, world peace, and economic justice. -

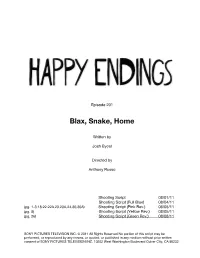

Blax, Snake, Home

Episode 201 Blax, Snake, Home Written by Josh Bycel Directed by Anthony Russo Shooting Script 08/01/11 Shooting Script (Full Blue) 08/04/11 (pg. 1-3,18,22,22A,23,23A,24,30,30A) Shooting Script (Pink Rev.) 08/05/11 (pg. 8) Shooting Script (Yellow Rev.) 08/05/11 (pg. 26) Shooting Script (Green Rev.) 08/08/11 SONY PICTURES TELEVISION INC. © 2011 All Rights Reserved No portion of this script may be performed, or reproduced by any means, or quoted, or published in any medium without prior written consent of SONY PICTURES TELEVISION INC. 10202 West Washington Boulevard Culver City, CA 90232 Happy Endings "Blax, Snake, Home" [201] a. Shooting Script (Pink Rev.) 08/05/11 CAST JANE .................................................................................................... Eliza Coupe ALEX ...............................................................................................Elisha Cuthbert DAVE...........................................................................................Zachary Knighton MAX ...................................................................................................... Adam Pally BRAD .......................................................................................Damon Wayans, Jr. PENNY ...............................................................................................Casey Wilson ANNOUNCER (V.O.)......................................................................................... TBD DARYL (GUY)..............................................................................Brandon -

The Atlanta Journal and Constitution March 29, 1998, Sunday, ALL EDITIONS

The Atlanta Journal and Constitution March 29, 1998, Sunday, ALL EDITIONS New 'leads' in King case invariably go nowhere David J. Garrow PERSPECTIVE; Pgs. C1, C2. LENGTH: 1775 words Do the never-ending claims of revelations concerning the April 4, 1968, assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. leave you a bit confused? What should we make of the assertion that U.S. Army military intelligence --- and President Lyndon B. Johnson --- were somehow involved? Why is Jack Ruby, who killed Lee Harvey Oswald two days after Oswald assassinated President John F. Kennedy in 1963, now turning up in the King assassination story? And what about former FBI agent Donald Wilson's claim that notes he pilfered from James Earl Ray's automobile and then concealed for 30 years contain a significant telephone number. Maybe you saw the ABC "Turning Point" documentary with Forrest Sawyer that demolished the Army intelligence allegations. Or perhaps you watched CBS' "48 Hours" broadcast with Dan Rather last week, which refuted the claims that some fictional character named "Raoul," acting in cahoots with Ruby, was responsible for both the Kennedy and the King assassinations. Don't worry. All of this actually is easier to follow than you may think, so long as you keep a relatively simply score card. All you need to do is remember the "three R's" --- Ray, "Raoul" and Ruby --- and also distinguish the "three P's" --- William F. Pepper, Gerald Posner and Marc Perrusquia. Ray you know. Now 70 years old and seriously ill, Ray pleaded guilty to King's slaying in 1969 but has spent the past 29 years trying to withdraw his plea. -

Characters Reunite to Celebrate South Dakota's Statehood

2 x 2" ad 2 x 2" ad May 24 - 30, 2019 Buy 1 V A H A G R Z U N Q U R A O C Your Key 2 x 3" ad A M U S A R I C R I R T P N U To Buying Super Tostada M A R G U L I E S D P E T H N P B W P J M T R E P A Q E U N and Selling! @ Reg. Price 2 x 3.5" ad N A M M E E O C P O Y R R W I get any size drink FREE F N T D P V R W V C W S C O N One coupon per customer, per visit. Cannot be combined with any other offer. X Y I H E N E R A H A Z F Y G -00109093 Exp. 5/31/19 WA G P E R O N T R Y A D T U E H E R T R M L C D W M E W S R A Timothy Olyphant (left) and C N A O X U O U T B R E A K M U M P C A Y X G R C V D M R A Ian McShane star in the new N A M E E J C A I U N N R E P “Deadwood: The Movie,’’ N H R Z N A N C Y S K V I G U premiering Friday on HBO.