Electric Vehicle Procurement Best Practices Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vehicle Conversions, Retrofits, and Repowers ALTERNATIVE FUEL VEHICLE CONVERSIONS, RETROFITS, and REPOWERS

What Fleets Need to Know About Alternative Fuel Vehicle Conversions, Retrofits, and Repowers ALTERNATIVE FUEL VEHICLE CONVERSIONS, RETROFITS, AND REPOWERS Acknowledgments This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) under Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308 with Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC, the Manager and Operator of the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. This work was made possible through funding provided by National Clean Cities Program Director and DOE Vehicle Technologies Office Deployment Manager Dennis Smith. This publication is part of a series. For other lessons learned from the Clean Cities American Recovery and Reinvestment (ARRA) projects, please refer to the following publications: • American Recovery and Reinvestment Act – Clean Cities Project Awards (DOE/GO-102016-4855 - August 2016) • Designing a Successful Transportation Project – Lessons Learned from the Clean Cities American Recovery and Reinvestment Projects (DOE/GO-102017-4955 - September 2017) Authors Kay Kelly and John Gonzales, National Renewable Energy Laboratory Disclaimer This document is not intended for use as a “how to” guide for individuals or organizations performing a conversion, repower, or retrofit. Instead, it is intended to be used as a guide and resource document for informational purposes only. VEHICLE TECHNOLOGIES OFFICE | cleancities.energy.gov 2 ALTERNATIVE FUEL VEHICLE CONVERSIONS, RETROFITS, AND REPOWERS Table of Contents Introduction ...............................................................................................................................................................5 -

Alternative Fuels, Vehicles & Technologies Feasibility

ALTERNATIVE FUELS, VEHICLES & TECHNOLOGIES FEASIBILITY REPORT Prepared by Eastern Pennsylvania Alliance for Clean Transportation (EP-ACT)With Technical Support provided by: Clean Fuels Ohio (CFO); & Pittsburgh Region Clean Cities (PRCC) Table of Contents Analysis Background: .................................................................................................................................... 3 1.0: Introduction – Fleet Feasibility Analysis: ............................................................................................... 3 2.0: Fleet Management Goals – Scope of Work & Criteria for Analysis: ...................................................... 4 Priority Review Criteria for Analysis: ........................................................................................................ 4 3.0: Key Performance Indicators – Existing Fleet Analysis ............................................................................ 5 4.0: Alternative Fuel Options – Summary Comparisons & Conclusions: ...................................................... 6 4.1: Detailed Propane Autogas Options Analysis: ......................................................................................... 7 Propane Station Estimate ......................................................................................................................... 8 (Station Capacity: 20,000 GGE/Year) ........................................................................................................ 8 5.0: Key Recommended Actions – Conclusion -

The Different Types of AC Power Connectors in North America

The Different Types of AC Power Connectors in North America White Paper 20 Revision 2 by James Spitaels Contents > Executive summary Click on a section to jump to it Introduction 2 A confusing array of AC power plugs and receptacles exist to deliver power to various electronic loads. This Connectors for multiple 2 white paper describes the different types of connect- applications ors used to power computer equipment in North America. An illustration guide is provided at the end of An international standard 2 the paper to help identify the various connectors by North American standard AC 4 appearance and size. connectors Safety issues 5 Conclusion 7 Resources 8 Appendix 9 white papers are now part of the Schneider Electric white paper library produced by Schneider Electric’s Data Center Science Center [email protected] The Different Types of AC Power Connectors in North America Introduction The connection of electronic equipment to the AC power supply is usually accomplished using detachable connectors. The alternative of "hard-wiring" equipment to the building wiring makes service and movement of equipment more costly and less convenient. Therefore, many types of connectors exist. As a result, much confusion is generated as to what the various connection types are, when they are used, and what they should look like. This white paper describes the different types of connectors used for powering computer equipment in North America, including internationally recognized connectors. A guide for identifying the connectors is provided as a reference (see Appendix) to help identify particu- lar connectors by name, appearance, and size. -

Reducing Air Emissions Through Alternative Transportation Strategies

Reducing Air Emissions Through Alternative Transportation Strategies New Jersey Clean Air Council Public Hearing April 8, 2014 Hearing Chair: Sara Bluhm Clean Air Council Chair: Joseph Constance Editor: Melinda Dower NJ CAC 2014 Hearing Report Page | 1 New Jersey Clean Air Council Members Joseph Constance, Chairman Kenneth Thoman,Vice-Chairman Leonard Bielory, M.D. Sara Bluhm Manuel Fuentes-Cotto, P.E. Michael Egenton Mohammad “Ferdows” Ali, Ph.D. Howard Geduldig, Esq. Toby Hanna, P.E. Robert Laumbach, M.D. Pam Mount Richard E. Opiekun, Ph.D. James Requa, Ed.D. Nicky Sheats, Esq., Ph.D. Joseph Spatola, Ph.D. New Jersey Clean Air Council Website http://www.state.nj.us/dep/cleanair NJ CAC 2014 Hearing Report Page | 2 Table of Contents Page I. INTRODUCTION ……………………………………………………………………… 4 II. OVERVIEW ……………………………………………………………………………. 4 III. RECOMMENDATIONS ……………………………………………………….……… 10 IV. SUMMARY OF TESTIMONY† ………………………………………………….…… 14 A. Jim Appleton ………………………………………………..……….…… 14 B. Daniel Birkett ………………………………………………………….… 14 C. Andy Swords ……………………………………….…………………... 14 D. Matt Solomon ……………………………………………………………. 15 E. Julie Becker …………………………………………………..……..…... 16 F. Robert Gibbs, Esq. ………………………………….………………..….. 16 G. William Wells ………………………………………..………………..…. 17 H. Mark Giuffre …………………………………………………………….. 17 I. Jane Kozinski, Asst. Commissioner, NJDEP ……………………………. 18 J. Chuck Feinberg …………………………………………………………. 19 K. Raymond Albrecht, P.E. …………………………………………………. 19 L. Nicky Sheats, Ph.D., Esq.………………………………………………… 20 M. John Iannarelli ……………………………………………………….…. -

Morgan Ellis Climate Policy Analyst and Clean Cities Coordinator DNREC [email protected] 302.739.9053

CLEAN TRANSPORTATION IN DELAWARE WILMAPCO’S OUR TOWN CONFERENCE THE PRESENTATION 1) What are alterative fuels? 2) The Fuels 3) What’s Delaware Doing? WHAT ARE ALTERNATIVE FUELED VEHICLES? • “Vehicles that run on a fuel other than traditional petroleum fuels (i.e. gas and diesel)” • Propane • Natural Gas • Electricity • Biodiesel • Ethanol • Hydrogen THERE’S A FUEL FOR EVERY FLEET! DELAWARE’S ALTERNATIVE FUELS • “Vehicles that run on a fuel other than traditional petroleum fuels (i.e. gas and diesel)” • Propane • Natural Gas • Electricity • Biodiesel • Ethanol • Hydrogen THE FUELS PROPANE • By-Product of Natural Gas • Compressed at high pressure to liquefy • Domestic Fuel Source • Great for: • School Busses • Step Vans • Larger Vans • Mid-Sized Vehicles COMPRESSED NATURAL GAS (CNG) • Predominately Methane • Uses existing pipeline distribution system to deliver gas • Good for: • Heavy-Duty Trucks • Passenger cars • School Buses • Waste Management Trucks • DNREC trucks PROPANE AND CNG INFRASTRUCTURE • 8 Propane Autogas Stations • 1 CNG Station • Fleet and Public Access with accounts ELECTRIC VEHICLES • Electricity is considered an alternative fuel • Uses electricity from a power source and stores it in batteries • Two types: • Battery Electric • Plug-in Hybrid • Great for: • Passenger Vehicles EV INFRASTRUCTURE • 61 charging stations in Delaware • At 26 locations • 37,000 Charging Stations in the United States • Three types: • Level 1 • Level 2 • D.C. Fast Charging TYPES OF CHARGING STATIONS Charger Current Type Voltage (V) Charging Primary Use Time Level 1 Alternating 120 V 2 to 5 miles Current (AC) per hour of Residential charge Level 2 AC 240 V 10 to 20 miles Residential per hour of and charge Commercial DC Fast Direct Current 480 V 60 to 80 miles (DC) per 20 min. -

Open PDF File, 176.5 KB, for 2018 Mass Clean Cities Annual Report

2018 Transportation Technology Deployment Report: Massachusetts Clean Cities Expanded Edition March 2019 DRAFT The U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Clean Cities program advances the nation's economic, environmental, and energy security by supporting local actions to reduce petroleum use in transportation. A national network of nearly 100 Clean Cities coalitions brings together stakeholders in the public and private sectors to deploy alternative and renewable fuels, idle-reduction measures, fuel economy improvements, and new transportation technologies, as they emerge. Every year, each Clean Cities coalition submits to DOE an annual report of its activities and accomplishments for the previous calendar year. Coalition coordinators, who lead the local coalitions, provide information and data via an online database managed by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). The data characterize membership, funding, projects, and activities of the coalitions. The coordinators also submit data on the sales of alternative fuels, deployment of alternative fuel vehicles and hybrid electric vehicles, idle-reduction initiatives, fuel economy activities, and programs to reduce vehicle miles traveled. NREL and DOE analyze the data and translate them into petroleum-use and greenhouse gas reduction impacts for individual coalitions and the program as a whole. This report summarizes those impacts for Massachusetts Clean Cities. To view aggregated data for all local coalitions that participate in the Clean Cities program, visit cleancities.energy.gov/accomplishments. -

Understanding Long-Term Evolving Patterns of Shared Electric

Experience: Understanding Long-Term Evolving Patterns of Shared Electric Vehicle Networks∗ Guang Wang Xiuyuan Chen Fan Zhang Rutgers University Rutgers University Shenzhen Institutes of Advanced [email protected] [email protected] Technology, CAS [email protected] Yang Wang Desheng Zhang University of Science and Rutgers University Technology of China [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT CCS CONCEPTS Due to the ever-growing concerns on the air pollution and • Networks → Network measurement; Mobile networks; energy security, many cities have started to update their Cyber-physical networks. taxi fleets with electric ones. Although environmentally friendly, the rapid promotion of electric taxis raises prob- KEYWORDS lems to both taxi drivers and governments, e.g., prolonged Electric vehicle; mobility pattern; charging pattern; evolving waiting/charging time, unbalanced utilization of charging experience; shared autonomous vehicle infrastructures and reduced taxi supply due to the long charg- ing time. In this paper, we make the first effort to understand ACM Reference Format: the long-term evolving patterns through a five-year study Guang Wang, Xiuyuan Chen, Fan Zhang, Yang Wang, and Desh- on one of the largest electric taxi networks in the world, i.e., eng Zhang. 2019. Experience: Understanding Long-Term Evolving the Shenzhen electric taxi network in China. In particular, Patterns of Shared Electric Vehicle Networks. In The 25th Annual we perform a comprehensive measurement investigation International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking (Mo- called ePat to explore the evolving mobility and charging biCom ’19), October 21–25, 2019, Los Cabos, Mexico. ACM, New York, patterns of electric vehicles. -

How Practical Are Alternative Fuel Vehicles?

How Practical Are Alternative Fuel Vehicles? Many of us have likely considered an alternative fuel vehicle at some point in our lives. Balancing the positives and negatives is a tricky process and varies greatly based on our personal situations. However, many of the negatives that previously created hesitancy have changed in recent years. Below, we have outlined a few of the most commonly mentioned negatives regarding the two leading alternative fuel vehicle types: Flex Fuel vehicles and Electric/Hybrid vehicles. Then, you can decide for yourself whether one of these vehicle types are practical for you! Cost – How much does the vehicle cost to purchase and operate? Flex Fuel: Flex Fuel vehicles typically cost about the same as a gasoline vehicle.1 For fuel cost, E85 typically costs slightly less than gasoline, however, due to decreased efficiency has a slightly higher cost per mile than gasoline.2 Overall, a Flex Fuel vehicle is likely to be slightly more expensive than a gasoline counterpart. Electric/Hybrid: This situation varies quite a bit depending on where you live. Electric vehicles and hybrid vehicles often cost considerably more than a conventional gasoline vehicle. For example, a plug-in hybrid will cost around $4000-$8000 more than a conventional model.3 However, there are federal rebates and local rebates that can refund thousands of dollars from the purchase price. Electric/Hybrid vehicles also tend to save money on fuel, with the possibility of saving thousands of dollars over the lifetime of the vehicle.4 Whether these rebates and fuel cost savings will eventually account for the higher purchase price can be estimated with comparison tools. -

EPRI Journal--Driving the Solution: the Plug-In Hybrid Vehicle

DRIVING THE SOLUTION THE PLUG-IN HYBRID VEHICLE by Lucy Sanna The Story in Brief As automakers gear up to satisfy a growing market for fuel-efficient hybrid electric vehicles, the next- generation hybrid is already cruis- ing city streets, and it can literally run on empty. The plug-in hybrid charges directly from the electricity grid, but unlike its electric vehicle brethren, it sports a liquid fuel tank for unlimited driving range. The technology is here, the electricity infrastructure is in place, and the plug-in hybrid offers a key to replacing foreign oil with domestic resources for energy indepen- dence, reduced CO2 emissions, and lower fuel costs. DRIVING THE SOLUTION THE PLUG-IN HYBRID VEHICLE by Lucy Sanna n November 2005, the first few proto vide a variety of battery options tailored 2004, more than half of which came from Itype plugin hybrid electric vehicles to specific applications—vehicles that can imports. (PHEVs) will roll onto the streets of New run 20, 30, or even more electric miles.” With growing global demand, particu York City, Kansas City, and Los Angeles Until recently, however, even those larly from China and India, the price of a to demonstrate plugin hybrid technology automakers engaged in conventional barrel of oil is climbing at an unprece in varied environments. Like hybrid vehi hybrid technology have been reluctant to dented rate. The added cost and vulnera cles on the market today, the plugin embrace the PHEV, despite growing rec bility of relying on a strategic energy hybrid uses battery power to supplement ognition of the vehicle’s potential. -

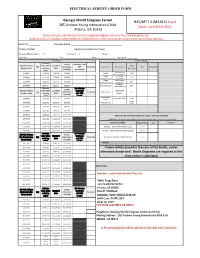

IEEE/MTT-S IMS2021 Event 285 Andrew Young International Blvd

ELECTRICAL SERVICE ORDER FORM Georgia World Congress Center IEEE/MTT-S IMS2021 Event 285 Andrew Young International Blvd. Dates: June 8-10, 2021 Atlanta, GA 30313 Orders may be submitted via email at [email protected] or online at www.gwcca.org Advance rates are available when orders are submitted via online 21 calendars prior to first day of show opening Booth No._________ Company Name _________________________________________ Primary Contact __________________________ Signature to Authorize Charge ___________________________________ Primary Phone No. ( )_________________ Fax No. ( )________________ Email: ____________________________ Address_________________________ City______________________ State_______________ Zip Code _________ ELECTRICAL SPECIAL SERVICES Advance Onsite Overhead add 120 Volt 1 Phase Rate when Standard Rate Qty Rate (Labor 50% Total Cost Item Name Description Qty Total Cost (single outlet) ordering Rate (per unit) included) (as needed) online 1000 watt can 5 AMPS $140.00 $169.40 $228.69 Par 64 $450 light installed in Single 25ft single 10 AMPS $210.60 $254.82 $290.00 $23 Extension Cord receptacle Single 50 ft single 15 AMPS $212.75 $257.42 $331.00 $37 Extension Cord receptacle 4 Outlet 20 AMPS $247.25 $301.17 $382.00 Quad Extension receptacle box $24 Advance 20- 60 amps Onsite 208 Volt 1 Phase Rate when Standard Overhead Receptacle Qty Rate (Labor Total Cost Multi-outlet $15 (single outlet) ordering Rate add 50% adapter included) online to rate Distribution 20 AMPS $276.00 $331.00 $438.00 100A-200A Panel $288 Panel -

Making Markets for Hydrogen Vehicles: Lessons from LPG

Making Markets for Hydrogen Vehicles: Lessons from LPG Helen Hu and Richard Green Department of Economics and Institute for Energy Research and Policy University of Birmingham Birmingham B15 2TT United Kingdom Hu: [email protected] Green: [email protected] +44 121 415 8216 (corresponding author) Abstract The adoption of liquefied petroleum gas vehicles is strongly linked to the break-even distance at which they have the same costs as conventional cars, with very limited market penetration at break-even distances above 40,000 km. Hydrogen vehicles are predicted to have costs by 2030 that should give them a break-even distance of less than this critical level. It will be necessary to ensure that there are sufficient refuelling stations for hydrogen to be a convenient choice for drivers. While additional LPG stations have led to increases in vehicle numbers, and increases in vehicles have been followed by greater numbers of refuelling stations, these effects are too small to give self-sustaining growth. Supportive policies for both vehicles and refuelling stations will be required. 1. Introduction While hydrogen offers many advantages as an energy vector within a low-carbon energy system [1, 2, 3], developing markets for hydrogen vehicles is likely to be a challenge. Put bluntly, there is no point in buying a vehicle powered by hydrogen, unless there are sufficient convenient places to re-fuel it. Nor is there any point in providing a hydrogen refuelling station unless there are vehicles that will use the facility. What is the most effective way to get round this “chicken and egg” problem? Data from trials of hydrogen vehicles can provide information on driver behaviour and charging patterns, but extrapolating this to the development of a mass market may be difficult. -

The Future of Transportation Alternative Fuel Vehicle Policies in China and United States

Clark University Clark Digital Commons International Development, Community and Master’s Papers Environment (IDCE) 12-2016 The uturF e of Transportation Alternative Fuel Vehicle Policies In China and United States JIyi Lai [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.clarku.edu/idce_masters_papers Part of the Environmental Studies Commons Recommended Citation Lai, JIyi, "The uturF e of Transportation Alternative Fuel Vehicle Policies In China and United States" (2016). International Development, Community and Environment (IDCE). 163. https://commons.clarku.edu/idce_masters_papers/163 This Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Master’s Papers at Clark Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Development, Community and Environment (IDCE) by an authorized administrator of Clark Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The Future of Transportation Alternative Fuel Vehicle Policies In China and United States Jiyi Lai DECEMBER 2016 A Masters Paper Submitted to the faculty of Clark University, Worcester, Massachusetts, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the department of IDCE And accepted on the recommendation of ! Christopher Van Atten, Chief Instructor ABSTRACT The Future of Transportation Alternative Fuel Vehicle Policies In China and United States Jiyi Lai The number of passenger cars in use worldwide has been steadily increasing. This has led to an increase in greenhouse gas emissions and other air pollutants, and new efforts to develop alternative fuel vehicles to mitigate reliance on petroleum. Alternative fuel vehicles include a wide range of technologies powered by energy sources other than gasoline or diesel fuel.