Recent Trends and Developments in Educational Psychology: Chinese and American Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Schocken Book of Contemporary Jewish Fiction 1St Edition Download Free

THE SCHOCKEN BOOK OF CONTEMPORARY JEWISH FICTION 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Ted Solotaroff | 9780805210651 | | | | | The Schocken book of contemporary Jewish fiction Paula MacLeod. Schocken Books is an offspring of the Schocken Verlaga publishing company that was established in Berlin in with a second office in Prague by the Schocken Department Store owner Salman Schocken. Pass it on! When you buy a book, we donate a book. Our story opens in an Austrian city, two generations before the Holocaust, where almost all of the Jews have converted to Christianity. On the Pleasure of Hating. Where the Jews Aren't From the acclaimed author of The Man Without a Face, the previously untold story of the Jews in twentieth- century Russia that reveals the complex, strange, and heart-wrenching truth behind Community Reviews. Please try again later. Natalya added it Apr 01, Geraldo Rivera. Paperbackpages. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. We are experiencing technical difficulties. You can help Wikipedia by expanding it. Ended: The Schocken Book of Contemporary Jewish Fiction 1st edition 17, PDT. Read more His Panic. Skip to main content. Republics, Nations and Tribes. About The Schocken Book of Contemporary Jewish Fiction This landmark anthology brings together some of the best stories written in the last thirty years by and about American Jews. This landmark anthology brings together some of the best stories written in the last thirty years by and about American Jews. This book is not yet featured on Listopia. Books by Ted Solotaroff. David Plouffe. Autodafe 2. Also available from:. Alfaguara Bruguera Ediciones B Santillana. Nina Shengold and Eric Lane. -

Six Tikunim for Israel at 60

For Educational Use Only Six T Six Tikkunim for Israel's Sixtieth Year In celebration and commemoration of Israel’s sixtieth anniversary, we propose six Tikkunim . The idea of Tikkun positions people in partnership with God, assuming responsibility for our world. By the same token, we invite Jews in Israel and abroad to share the responsibility for the present and future State of Israel, through meaningful learning and experience of current dilemmas of the sixty- year-old/young country. Halachah offers an educational frame for the number “sixty”, when it claims that food will be considered kosher even if it has a non-kosher ingredient, when the kosher ingredients of the food are sixty times greate r than the non kosher Thinking within this . ָטֵ ל ְִִ י ingredient. This is termed: Nullified by Sixty 1 framework as well as the framework of Tikkun Olam, led us to identify six Tikkunim for Israel’s sixtieth year. We hope that these Tikkunim will serve as an invitation for contemplation and action on that which requires mending and in turn become sixty times greater than other Israeli challenges. In the following document you will find six gates for six Tikkunim . Each gate is thematically inspired by one of the books of the Mishnah: Tikkun of Time תיקו הזמ – Zeraim (1 Tikkun of Shabbat תיקו שבת – Mo’ed (2 Tikkun of Gender תיקו המגדר – Nashim (3 Tikkun of Conservation תיקו השימור - Nezikin (4 Tikkun of the Sacred Place and Space תיקו המקו הקדוש - Kodashim (5 Tikkun of Social Ethics תיקו הכשרות החברתית – Toharot (6 1 " "ָ ל אִ רִ י ֶַ רָה [ ְטֵלִ י ] ְִִ י " ( תלמוד בבלי , קודשי , חולי , פרק ז ', ד+ צ" ח א ' גמרא) 1 Each Tikkun gate includes: a verse introducing the key issue, an essential question, a Jewish Text, an Israeli song and a contemporary Israeli thought. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Sarah R. Irving Intellectual networks, language and knowledge under colonialism: the work of Stephan Stephan, Elias Haddad and Tawfiq Canaan in Palestine, 1909-1948 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Literatures, Languages and Cultures University of Edinburgh 2017 Declaration: This is to certify that that the work contained within has been composed by me and is entirely my own work. No part of this thesis has been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. Signed: 16th August 2017 2 Intellectual networks, language and knowledge under colonialism: the work of Stephan Stephan, Elias Haddad and Tawfiq Canaan in Palestine, 1909-1948 Table of Contents -

Vol. 05 No. 3 Religious Educator

Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel Volume 5 Number 3 Article 15 9-1-2004 Vol. 05 No. 3 Religious Educator Religious Educator Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/re BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Educator, Religious. "Vol. 05 No. 3 Religious Educator." Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel 5, no. 3 (2004). https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/re/vol5/iss3/15 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. THE RELIGIOUS EDUCATOR • PERSPECTIVES ON THE RESTORED GOSPEL Counsel and Correction INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Living a Life in Crescendo Literary Features of the Gospels Four Imperatives for Religious Educators President Gordon B. Hinckley VOL 5 NO 3 • 2004 Counsel and Correction Paul V. Johnson Roles of Support L. Jill Johnson Living a Life in Crescendo Grant C. Anderson Our Legacy of Religious Education Stephen K. Iba Simon and the Woman Who Anointed Jesus’s Feet Gaye Strathearn RELIGIOUS STUDIES CENTER • BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY Sorting Out the Seven Marys in the New Testament Blair G. Van Dyke and Ray L. Huntington How to Ask Questions That Invite Revelation Four Imperatives for Alan R. Maynes “Written, That Ye Might Believe”: Religious Educators Literary Features of the Gospels Julie M. Smith President Gordon B. Hinckley A Viewpoint on the Supposedly Lost Gospel Q Thomas A. Wayment Teacher, Scholar, Administrator: A Conversation with Robert J. -

Catalog 208: New Arrivals Folded and Gathered Signatures

BETWEENBETWEEN THETHE COVERSCOVERS RARERARE BOOKSBOOKS Catalog 208: New Arrivals Folded and Gathered Signatures 1 Ernest HEMINGWAY A Moveable Feast New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons (1964) $3500 Unbound folded and gathered signatures. Eight signatures (including one of photographs), the first and last signature with endpapers attached. Page edges untrimmed, and consequently the signatures have minor height variations. Fine. A collection of vignettes inspired by the author’s profound nostalgia for the halcyon days of his early career. This is the final pre-binding state before the signatures are sewn together and the pages trimmed. Rare in this format. [BTC#334030] 2 Robert LOWELL Notebook 1967-68 Farrar, Straus, Giroux: New York (1969) $2750 First edition. Fine in about fine dustwrapper with a small crease on the rear flap. From the library of Pulitzer Prize-winning author Peter Taylor and his wife, the National Book Award-nominated poet Eleanor Ross Taylor. Inscribed by Lowell using his nickname: “For Peter and Eleanor with all the love I can scribble. Cal.” Lowell and Peter Taylor were very close friends and colleagues and were instrumental on each other’s careers. They both attended Kenyon College where they were roommates and studied under Allen Tate and John Crowe Ransom. [BTC#355686] BETWEEN THE COVERS RARE BOOKS CATALOG 208: NEW ARRIVALS 112 Nicholson Rd. Terms of Sale: Images are not to scale. Dimensions of items, including artwork, are given width Gloucester City, NJ 08030 first. All items are returnable within 10 days if returned in the same condition as sent. Orders may be reserved by telephone, fax, or email. -

Israël L'édition En Israël Février 2015

L’édition en Israël Étude réalisée par Karen Politis Département Études du BIEF Février 2015 Remerciements Je remercie les professionnels du livre que j’ai rencontrés à Tel-Aviv et Jérusalem d’avoir accepté de me recevoir et de m’avoir consacré un peu de leur temps. Je les remercie très sincèrement pour la qualité de nos échanges, pour leur enthousiasme à me parler de leur métier et pour leur vision éclairée du marché du livre en Israël. 2 Sommaire INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 5 SYNTHESE ................................................................................................................................ 6 INDICATEURS SOCIOECONOMIQUES, DEMOGRAPHIQUES ET LINGUISTIQUES ........................ 7 LA NOUVELLE LOI SUR LE PRIX DU LIVRE ................................................................................. 9 A. RAPPEL DU CONTEXTE ENTRE 2008 ET 2013 .......................................................................... 9 B. LA LOI ET SA FILIATION FRANÇAISE ........................................................................................ 10 C. LES GRANDS PRINCIPES DE LA LOI ......................................................................................... 11 D. MISE EN ŒUVRE DE LA LOI .................................................................................................. 13 LES ACTEURS DU MONDE DE L’EDITION EN ISRAËL ................................................................ 16 A. LE PAYSAGE -

December 2017

December 2017 Peter Harrington london All items are fully described and photographed at peterharrington.co.uk 1 Christmas 2017 opening hours: Dover Street Mon 27 Nov – Sat 23 Dec Mon–Fri: 10am–7pm Sat: 10am–6pm Sun: closed Sun 24 Dec – Mon 1 Jan 2018: closed Fulham Road Mon 27 Nov – Sat 23 Dec Mon–Thur: 10am–7pm Fri & Sat: 10am–6pm Sun: closed Sun 24 Dec – Tue 26 Dec: closed Wed 27 Dec – Sat 30 Dec: 10am–6pm Sun 31 Dec – Mon 1 Jan 2017: closed Tues 2 Jan 2018: Normal business hours resume Front cover image from Jean de Brunhoff’s Babar and Father Christmas, item 22 VAT no. gb 701 5578 50 Image opposite adapted from Roger Duvoisin’s small archive of Christmas greetings cards, item 66 Peter Harrington Limited. Registered office: WSM Services Limited, Connect House, 133–137 Alexandra Road, Wimbledon, London SW19 7JY. Design: Nigel Bents; Photography: Ruth Segarra Registered in England and Wales No: 3609982 Peter Harrington london catalogue 141 All items from this catalogue are on exhibition at Fulham Road chelsea mayfair Peter Harrington Peter Harrington 100 Fulham Road 43 Dover Street London sw3 6hs London w1s 4ff uk 020 7591 0220 uk 020 3763 3220 eu 00 44 7591 0220 eu 00 44 20 3763 3220 usa 011 44 7591 0220 usa 011 44 20 3763 3220 www.peterharrington.co.uk 1 1 1 tory of the books of the Press’” (Colin Franklin, per with a little offsetting to facing pastedown. A little The Private Presses, p. 60). rubbing to joints and extremities, a few small darkened (ASHENDENE PRESS.) ECCLESIASTI- areas to front board. -

The Upside of Evil (Tetzave) by Rabbi Ben Tzion Spitz Moshe Feiglin On

11 Adar Alef 5779 – Feb 16, 2019 BSD from God and cleave to divine service, God is overjoyed, and it The Upside of Evil (Tetzave) causes a divine light to spread forth. By Rabbi Ben Tzion Spitz May we always overcome our negative natural impulses and turn our inner demons into radiant light. Evil is unspectacular and always human, and Moshe Feiglin on the Latest Yisrael shares our bed and eats at our own table. -W. H. Auden Hayom Poll: ZEHUT at 5 Mandates In describing the construction plans of the Holy Tabernacle, the Torah adds a short line about the fuel needed to light the Menorah, the golden candelabrum, which was one of the special fixtures of the Tabernacle. It states as follows: “And thou shalt command the children of Israel, that they bring unto thee pure olive oil beaten for the light, to cause a lamp to burn continually.” – Exodus 27:22 The Berdichever focuses on the choice of words of “beating” the olive to get light. He compares the olive in this case to one’s evil inclination. The evil inclination is constantly enticing us to follow our base desires, to indulge in what is forbidden and to separate us from spiritual and divine service. The solution is to “beat” that desire and then elevate that very same desire, to channel it into divine service. To use that passion, that interest, that energy, in holy ventures. We need to consider that if we have some physical yearning, how much stronger should our yearning be for the infinite, for God? If we have some physical fear, how much stronger should our fear and awe of the divine be? Dear Friends, When we’ve managed to convert that evil inclination, those base Yes, this morning it looks like ZEHUT’s sun is beginning to shine, desires into spiritual energy, into holy actions, then that evil has thank God. -

ITHL 2020 Adult Books Catalogue

New Books from Israel • Fall 2020 THE INStitUTE FOR THE TRANSLAtiON Of HEBREW LitERATURE THE INSTITUTE FOR THE TRANSLATION OF HEBREW LITERATURE NEW BOOKS FROM ISRAEL Fall 2020 CONTENTS Yishai Sarid, Victorious ..............................................................................2 Nurith Gertz, What Was Lost to Time .......................................................3 Amalia Rosenblum, Saul Searching ...........................................................4 Shulamit Lapid, Butterfly in the Shed ........................................................5 Ronit Matalon, Snow .................................................................................6 Roy Chen, Souls .........................................................................................7 Dror Burstein, Present ...............................................................................8 Yossi Sucary, Amzaleg ................................................................................9 Yossi Sucary, Benghazi-Bergen-Belsen ...................................................... 10 Yair Assulin, The Drive ............................................................................ 11 Eran Bar-Gil, Of Death and Honey .......................................................... 12 Dana Heifetz, Dolphins in Kiryat Gat ...................................................... 13 Rinat Schnadower, Showroom .................................................................. 14 Eldad Cohen, Wake Up Mom .................................................................. -

The Following Is a List of Foreign Sales Made by Taryn Fagerness Agency

The following is a list of foreign sales made by Taryn Fagerness Agency. It does not reflect any expirations or reversions. A PERFECT MESS by Eric Abrahamson and David H. Freedman Anthony Arnove, Roam Agency France (Editions Flammarion) Lithuania (Eugrimas) TOUCH by Jus Accardo Kevan Lyon, Marsal Lyon Literary Agency France (Albin Michel Jeunesse) Hungary (Könyvmolykepzö) Poland (Dreams Lidia Mis-Nowak) Russia (AST) Turkey (Pegasus) UNTOUCHED by Jus Accardo Kevan Lyon, Marsal Lyon Literary Agency Hungary (Könyvmolykepzö) TOXIC by Jus Accardo Kevan Lyon, Marsal Lyon Literary Agency France (Albin Michel Jeunesse) Hungary (Könyvmolykepzö) Poland (Dreams Lidia Mis-Nowak) TREMBLE by Jus Accardo Kevan Lyon, Marsal Lyon Literary Agency France (Albin Michel Jeunesse) Hungary (Könyvmolykepzö) Poland (Dreams Lidia Mis-Nowak) COOL FOR THE SUMMER by Dahlia Adler Patricia Nelson, Marsal Lyon Literary Agency Brazil (Globo) GRIMSPACE, Sirantha Jax Series: Book 1 by Ann Aguirre Laura Bradford, Bradford Literary Agency Czech Republic (Fantom Print) Germany (Blanvalet) Japan (Hayakawa Publishing) Turkey (Artemis/Alfa) WANDERLUST, Sirantha Jax Series: Book 2 by Ann Aguirre Laura Bradford, Bradford Literary Agency Czech Republic (Fantom Print) Germany (Blanvalet) Turkey (Artemis/Alfa) DOUBLEBLIND, Sirantha Jax Series: Book 3 by Ann Aguirre Laura Bradford, Bradford Literary Agency Czech Republic (Fantom Print) Germany (Blanvalet) Turkey (Artemis/Alfa) KILLBOX, Sirantha Jax Series: Book 4 by Ann Aguirre Laura Bradford, Bradford Literary Agency Turkey (Artemis/Alfa) -

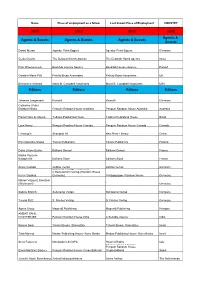

2019 2019 2019 2019 Agents & Scouts Agents & Scouts Agents

Name Place of employment as a fellow Last known Place of Employment COUNTRY 2019 2019 2019 2019 Agents & Agents & Scouts Agents & Scouts Agents & Scouts Scouts Daniel Mursa Agentur Petra Eggers Agentur Petra Eggers Germany Geula Geurts The Deborah Harris Agency The Deborah Harris Agency Israel Piotr Wawrzenczyk Book/lab Literary Agency Book/lab Literary Agency Poland Caroline Mann Plitt Felicity Bryan Associates Felicity Bryan Associates UK Beniamino Ambrosi Maria B. Campbell Associates Maria B. Campbell Associates USA Editors Editors Editors Editors Johanna Langmaack Rowohlt Rowohlt Germany Catherine (Cate) Elizabeth Blake Penguin Random House Australia Penguin Random House Australia Australia Flavio Rosa de Moura Todavia Publishing House Todavia Publishing House Brazil Lynn Henry Penguin Random House Canada Penguin Random House Canada Canada Li Kangqin Shanghai 99 New River Literary China Päivi Koivisto-Alanko Tammi Publishers Tammi Publishers Finland Dana Liliane Burlac Éditions Denoël Éditions Denoël France Maÿlis Vauterin- Bacqueville Editions Stock Editions Stock France Anvar Cukoski Aufbau Verlag Aufbau Verlag Germany Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt and C.Bertelsmann Verlag (Random House Karen Guddas Germany) Verlagsgruppe Random House Germany Marion Vazquez Boerzsei (Wichmann) ` ` Germany Sabine Erbrich Suhrkamp Verlag Suhrkamp Verlag Germany Teresa Pütz S. Fischer Verlag S. Fischer Verlag Germany Ágnes Orzóy Magvető Publishing Magvető Publishing Hungary AMBAR SAHIL CHATTERJEE Penguin Random House India A Suitable Agency India Ronnie -

Partial Vertical Integration in Telecommunication and Media Markets in Israel 1

Israel Economic Review Vol. 9, No. 1 (2011), 29–51 PARTIAL VERTICAL INTEGRATION IN TELECOMMUNICATION 1 AND MEDIA MARKETS IN ISRAEL DAVID GILO * AND YOSSI SPIEGEL ** 1. INTRODUCTION Partial vertical integration is common in many telecommunication and media markets in Israel. That is, there are many cases in which the supplier of an input holds a partial (often controlling) stake in the input’s customer (which we call the “distributor” for concreteness), or the distributor holds a partial ownership (often controlling) stake in the supplier. 2 This is in contrast to full vertical integration, in which the supplier holds 100% of the distributor’s equity, or the distributor holds 100% of the supplier’s equity. For example, since early 2010, when it took over Bezeq, Eurocom Communications Ltd. which imports Nokia cellular phones to Israel has an indirect control over Pelephone, which is the third largest cellular operator in Israel and buys cellular phones from Eurocom for its customers. However, even though Eurocom now indirectly controls Pelephone, its stake in Pelephone is far below 100%. Similarly, Bezeq International Ltd., which is fully owned by Bezeq, currently holds a 67% stake in Walla! Communications Ltd., which operates the Walla internet portal. Walla, Bezeq International and Bezeq, are (partially) vertically integrated because Walla requires internet-access services that Bezeq International supplies, and it also requires access to the infrastructure that Bezeq supplies. When the markets that the supplier or the distributor operate in are concentrated, as is the case in many telecommunication and media markets in Israel, vertical integration raises a concern for either “upstream foreclosure” – the vertically integrated firm will refuse to buy, or will buy at inferior terms from competing suppliers – or “downstream foreclosure” - the vertically integrated firm will refuse to sell, or will sell at inferior terms to competing distributors.