Precepts As Original Nature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Beginner's Guide to Meditation

ABOUT THE BOOK As countless meditators have learned firsthand, meditation practice can positively transform the way we see and experience our lives. This practical, accessible guide to the fundamentals of Buddhist meditation introduces you to the practice, explains how it is approached in the main schools of Buddhism, and offers advice and inspiration from Buddhism’s most renowned and effective meditation teachers, including Pema Chödrön, Thich Nhat Hanh, the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, Sharon Salzberg, Norman Fischer, Ajahn Chah, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, Shunryu Suzuki Roshi, Sylvia Boorstein, Noah Levine, Judy Lief, and many others. Topics include how to build excitement and energy to start a meditation routine and keep it going, setting up a meditation space, working with and through boredom, what to look for when seeking others to meditate with, how to know when it’s time to try doing a formal meditation retreat, how to bring the practice “off the cushion” with walking meditation and other practices, and much more. ROD MEADE SPERRY is an editor and writer for the Shambhala Sun magazine. Sign up to receive news and special offers from Shambhala Publications. Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala. A BEGINNER’S GUIDE TO Meditation Practical Advice and Inspiration from Contemporary Buddhist Teachers Edited by Rod Meade Sperry and the Editors of the Shambhala Sun SHAMBHALA Boston & London 2014 Shambhala Publications, Inc. Horticultural Hall 300 Massachusetts Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 www.shambhala.com © 2014 by Shambhala Sun Cover art: André Slob Cover design: Liza Matthews All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. -

The Precepts Support Us To: “Live and Be Lived for the Benefit of All Beings.”

The precepts support us to: “live and be lived for the benefit of all beings.” Blanche Hartman Precepts Practice Group What are the Precepts… Hui Neng, the sixth Zen ancestor, said “It is precisely Buddhist conduct that is the Buddha.” This means, as Peter Hershock notes, that the real Buddhist is seen “in terms of conduct – that is, his or her lived relations with others – and not according to any individually possessed marks or states of consciousness.” Buddhism rests on a deeply ethical foundation. The Buddha taught the principles of ethical living through- out his forty-five years of teaching. Although this ethical foundation parallels the ethical teachings of every major world religion in some ways, Buddhism is unique in the way the precepts are presented. Rather than reflecting moral judgments or declarations of “what is good” and “what is bad or evil,” the Buddha taught an active process of inquiry into that which is wholesome and that which is unwholesome. https://appamada.org/precepts-study Flint’s Teacher Blanche Hartman, in the 'The Hidden Lamp' p.102, says... I understand the precepts not as rules to follow, but more as, “Be very careful in this area of human life because there's a lot of suffering there, so pay attention to what you are doing,” Like a sign on a frozen pond that says, “Danger, thin ice,” rather than, “Shame on you!” Our vow is to help people end suffering, not to add to their suffering". Precepts are often written in a prohibitive form e.g. Do not steal..... -

BEYOND THINKING a Guide to Zen Meditation

ABOUT THE BOOK Spiritual practice is not some kind of striving to produce enlightenment, but an expression of the enlightenment already inherent in all things: Such is the Zen teaching of Dogen Zenji (1200–1253) whose profound writings have been studied and revered for more than seven hundred years, influencing practitioners far beyond his native Japan and the Soto school he is credited with founding. In focusing on Dogen’s most practical words of instruction and encouragement for Zen students, this new collection highlights the timelessness of his teaching and shows it to be as applicable to anyone today as it was in the great teacher’s own time. Selections include Dogen’s famous meditation instructions; his advice on the practice of zazen, or sitting meditation; guidelines for community life; and some of his most inspirational talks. Also included are a bibliography and an extensive glossary. DOGEN (1200–1253) is known as the founder of the Japanese Soto Zen sect. Sign up to learn more about our books and receive special offers from Shambhala Publications. Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala. Translators Reb Anderson Edward Brown Norman Fischer Blanche Hartman Taigen Dan Leighton Alan Senauke Kazuaki Tanahashi Katherine Thanas Mel Weitsman Dan Welch Michael Wenger Contributing Translator Philip Whalen BEYOND THINKING A Guide to Zen Meditation Zen Master Dogen Edited by Kazuaki Tanahashi Introduction by Norman Fischer SHAMBHALA Boston & London 2012 SHAMBHALA PUBLICATIONS, INC. Horticultural Hall 300 Massachusetts Avenue -

Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha Continued from Previous Page It Was Needed, Each One Doing a Little Bit More Voices to Bring the Garden to Life

Berkeley Zen Center August 2007 Newsletter Enlightenment, Faith, BZC Schedule and Practice August Sojun Talk, Sept. 30, 1995 Founder’s Ceremony oday I want to talk about faith and devo- Thursday, 8-2, 6:20 pm tion in Zen practice. Actually, I want to talk Friday, 8-3 , 6:40 am TTabout faith, enlightenment and practice, Half-Day Sitting because all three are necessary, and you might Sunday, 8-5 say that these are the three legs of Zen practice. Work Sesshin Day Actually, practice is devotion and faith is enlight- Sunday, 8-12 enment. When people think about Zen, what Kidzendo comes to mind is enlightenment as the main Saturday, 8-18 feature. But actually, faith is the foundation, and Bodhisattva Ceremony Saturday, 8-25, 9:30 am faith and enlightenment are inseparable. In all schools of Buddhism faith is an indispensable September factor, and Zen is just Buddhism. Two-Day Study Sitting Sometimes people think that Zen is something Saturday & Sunday, 9-1 & 9-2 a little to the side of Buddhism, but actually, Zen Founders Ceremony is what we call Buddha's practice. And when you Tuesday, 9-4, 6:20 pm practice, you are Buddha. So it's your practice, Wednesday, 9-5, 6:40 am and at the same time it's Buddha's practice. Kidzendo When you are completely engaged in practice, Saturday, 9-15 it's Buddha's practice. When you sit zazen, Half-Day Sitting Buddha is sitting zazen. Sunday, 9-16 The fundamental premise of our school is that Women’s Sitting ordinary beings and Buddha are not two. -

The Burmese Monk

Through the Looking-Glass An American Buddhist Life Bhikkhu Cintita Copyright 2014, Bhikkhu Cintita (John Dinsmore) This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 Unported Licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work, Under the following conditions: • Attribution — You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). • Noncommercial — You may not use this work for commercial purposes. • No Derivative Works — You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. With the understanding that: • Waiver — Any of the above conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder. • Public Domain — Where the work or any of its elements is in the public domain under applicable law, that status is in no way affected by the license. • Other Rights — In no way are any of the following rights affected by the license: • Your fair dealing or fair use rights, or other applicable copyright exceptions and limitations; • The author's moral rights; • Rights other persons may have either in the work itself or in how the work is used, such as publicity or privacy rights. • Notice — For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. Publication Data. Bhikkhu Cintita (John Dinsmore, Ph.D.), 1949 - Through the Looking Glass: An American Buddhist Life/ Bhikkhu Cintita. 1.Buddhism – Biography. © 2014. Cover design by Kymrie Dinsmore. Photo: Ashin Paññasīha and Ashin Cintita with lay devotees in Yangon in 2010. -

IN THIS ISSUE ABBOTT’S NEWS EMPTY CUP a COMMENT on FAITH Shudo Hannah Forsyth Katherine Yeo Karen Threlfall

Soto Zen Buddhism in Australia June 2016, Issue 64 IN THIS ISSUE ABBOTT’S NEWS EMPTY CUP A COMMENT ON FAITH Shudo Hannah Forsyth Katherine Yeo Karen Threlfall COMMITTEE NEWS MIRACLE OF TOSHOJI ONE BRIGHT PEARL Shona Innes Ekai Korematsu Osho Katrina Woodland VALE ZENKEI BLANCHE HARTMAN A MAGIC PLACE POEMS Shudo Hannah Forsyth Toshi Hirano Dan Carter, Andrew Holborn CULTIVATING FAITH RETREAT REFLEXION SOTO KITCHEN Ekai Korematsu Osho Peter Brammer Annie Bolitho CULTIVATING FAITH Cover calligraphy by Jinesh Wilmot 1 MYOJU IS A PUBLICATION OF JIKISHOAN ZEN BUDDHIST COMMUNITY INC Editorial Myoju Welcome to the Winter Solstice issue of Myoju, the first Editor: Ekai Korematsu of several issues with the theme Cultivating Faith. The Publications Committee: Hannah Forsyth, Christine cover image is calligraphy of enso with the character Faith Maingard, Katherine Yeo, Robin Laurie, Azhar Abidi inside it. The very first edition of Myoju in Spring 2000 had Myoju Coordinator: Robin Laurie an enso on the cover with a drawing of Ekai Osho in his Production: Darren Chaitman samu clothes making seating for the zendo in his garage. Website Manager: Lee-Anne Armitage An action based in great faith. IBS Teaching Schedule: Hannah Forsyth / Shona Innes Faith is a complex issue. It’s attached to phrases like ‘blind Jikishoan Calendar of Events: Shona Innes faith,’ which seem to trail a sense of mindless following and Contributors: Ekai Korematsu Osho, Shudo Hannah obedience. Forsyth, Katherine Yeo, Shona Innes, John Hickey, Karen Threlfall, Toshi Hirano, Peter Brammer, Katrina In that very first issue the meaning of Jikishoan is spelt out: Woodland, Andrew Holborn, Dan Carter and Annie jiki-direct, sho-realization an-hut: direct realisation hut. -

2006.08 Blanche Hartman (No Time to Waste).Pdf

Gay Buddhist Fellowship AUGUST / SEPTEMBER 2006 NEWSLETTER No Time to Waste The Gay Buddhist BY BLANCHE HARTMAN Fellowship supports Blanche Hartman is the former co-abbess of the San Francisco Zen Cen- ter. She is a dharma heir of Mel Weitsman and has been practicing Soto Buddhist practice in the Zen since 1969. She gave the following talk at GBF on March 5, 2006. 'm very glad to be with you here today. My teacher told me once, “Talk Gay men’s community. about what's right in front of you.” And so I will be talking today about Isomething I've talked about before: the deep consideration of how to live our It is a forum that life in the face of the fact that it is temporary. We have this gift of life, this opportunity to live this life that is given to us, and we don't know for how long. brings together the And we don't know what happens next. But we do therefore want to be awake in this life, to actually be here, to be present, to be aware, and not to sleep diverse Buddhist through it. We want to really deeply consider what can we do to make the gift of this life a gift for all of those around us. I went recently to a poetry reading, traditions to address and the poet, Kay Ryan, read this poem. As though the river were a floor, the spiritual concerns we position our table and chairs upon it, eat, and have conversation. of Gay men in the As it moves along we notice—as calmly as though dining room paintings were being replaced— San Francisco Bay Area, the changing scenes along the shore. -

Summer 1996 Wind Bell

•·.. \ Publication of Zen Center Vol. XXX i o. 2 Summer 1996 Contents News I Features Mountain Seat Ceremony for Shunbo Zenkei Blanche Hartman by Furyu Schroeder 8 On the Zafu, Off the Zafu, Out the Door by Barbara Wenger 20 Using Native Plants for Landscaping the New Tassajara Bathhouse by Diane Renshaw 28 Zen Center Loses a Giant Friend by Barbara Wenger 32 Sitting Together Under a Dead Tree by Wendy Johnson 34 Jerry Fuller, 1934-1996 by Meiya Wender 43 Dharma Talks Purely Involved Helping Others by Shunryu Suzuki Roshi 3 Right There Where You're Standing by Abbess Zenkei Hartman 37 Departments Related Zen Centers 46 Cover: A monk at Tassajara, photo by Heather Hiett Suzuki Roshi at Tassajara Purely Involved Helping Others Shunryu Suzuki Roshi I want to discuss with you how to apply practice to your everyday life. Whether you are a lay person or a priest, we are all Bodhisattvas. We are taking Bodhisattva vows and we are practicing t)1e Bodhisattva way. As you know, the Bodhisattva way is to help others as you help yourself, or to help others more, before you help yourself. That is the Bodhisattva way. When you try to figure out the relationship between zazen practice and your everyday life, you will see how important this point is. When you forget this point you cannot extend your practice to your everyday life, because as Buddhists we should see things "as it is." That is the most important point. When you practice zazen you don 't see anything, or think about anything. -

Zen Center Comes to the Lower Haight/ Hayes Valley

Zen Center Comes to the Lower Haight/ 1940s photo of Page and Buchanan Streets Hayes Valley Neighborhood—1969 (Zen Center down the Page St hill.) Zen Center’s Neighborhood Foundation (1970s) led the fight to transform the neighborhood photo: SF Public Library photo: Zen Center Archives This booklet was made specifically for friends and acquaintances from my early days in the 70s at the San Francisco Zen Center (SFZC). I would like to honor all the work SFZC did to transform the 300 Page Street neighborhood, and tell you about CommunityGrows, which has continued this transformation. Specifically, this booklet highlights only one of many transforma- tions SFZC made to the neighborhood, the development of Koshland Park. That project was a true catalyst in bringing the community together during tough times throughout San Francisco. It spurred neighborhood involvement that continues to this day. -Barbara Wenger 1973-The Beginning of Koshland Park Neighborhood Foundation’s Track Team-1970 photo: Zen Center Archives photo: Royston, Hanamoto, Beck & Abey Excerpt from SFZC’s Windbell, Summer 1975: In the predawn hours of a morning in March 1973, a terrible arson fire swept through a fifty-unit, four-story apartment building at 343 Page Street. The apartment building was destroyed, four people died, photo: Royston, Hanamoto, Beck & Abey and scores of tenants had to find new homes. As the burned out shell stood waiting for demolition, many 1974 Meeting to Design Koshland Park-UC Extension (now 55 Laguna) Here are some folks that were present: Issan Dorsey Margery Farrar Pam Chernoff Reb Anderson Charles Hoy Jay Simoneaux Rusa Chu Joe Cohen Miriam Bobkoff Louise Welch Ed Brown Dan Kaplan Amy Richmond Linda Hess Nancy Sheldon the Hudspeths Peter Overton Jane Hirshfield Daniel Koshland Jr. -

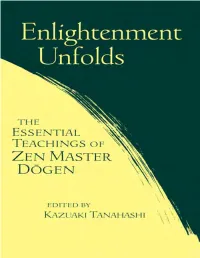

Enlightenment Unfolds Is a Sequel to Kaz Tanahashi’S Previous Collection, Moon in a Dewdrop, Which Has Become a Primary Source on Dogen for Western Zen Students

“Tanahashi is a writer and painter whose earlier collection, Moon in a Dewdrop, served as an introduction to the work of Dogen for many Western readers. This sequel collection draws from the complete range of Dogen’s writing. Some pieces have been widely translated and will be familiar to students of Zen, others have been reprinted from Moon in a Dewdrop, and still others appear here in English for the first time. Tanahashi worked with a number of co-translators, all of them Zen practitioners in Dogen’s lineage, and the result is an accessible and admirably consistent text. This is particularly impressive given the somewhat eccentric nature of Dogen’s prose, which can approach poetry and as a vehicle for Zen teachings often exists at the outer limits of usefulness of language in conveying meaning. Students of Zen will find this text essential.” —Mark Woodhouse, Library Journal ABOUT THE BOOK Enlightenment Unfolds is a sequel to Kaz Tanahashi’s previous collection, Moon in a Dewdrop, which has become a primary source on Dogen for Western Zen students. Dogen Zenji (1200– 1253) is unquestionably the most significant religious figure in Japanese history. Founder of the Soto school of Zen (which emphasizes the practice of zazen or sitting meditation), he was a prolific writer whose works have remained popular for six hundred years. Enlightenment Unfolds presents even more of the incisive and inspiring writings of this seminal figure, focusing on essays from his great life work, Treasury of the True Dharma Eye, as well as poems, talks, and correspondence, much of which appears here in English for the first time. -

Winter 1996 Wind Bell

.. •• (.,.. ,,.~ '\.. f Publication of Zen Center Vol. XXX No. I Winter 1996 CONTENTS Understanding Ordinary Mind is Buddha by Suzuki Roshi, p. 3 September Dharma Transmission Ceremony at Tassajara: Abbot Sojun Weitsman Speaks About the Ceremony, p. 6 Embodying the Dharma: The Willingness to be Present by Pat Phelan, p. 8 The Chapel Hill Zen Group: Past and Present, p. 12 Reflections on Receiving Dharma Transmission by Gil Fronsdal, p. 13 Gil Fronsdal and the Mid-Peninsula Insight Meditation Group, p. I 8 Tassajara Stone Dining Room by Furyu Schroeder; p. 20 The Wall by Cabin One by Bill Steele, p. 22 Entering the Dharma by Mick Sopko, p. 26 A New Book by Darlene Cohen Arthritis: Stop Suffering, Start Moving, p. 36 A Translation of the Eihei Shingi by Taigen Leighton and Shohaku Okumura, p. 37 Wind Bell Editor; p. 39 Finding Out What it Means to be Ordained by Abbot Mel Weitsman, p. 40 An Announcement: On Sunday February 4. 1996, Shunbo Zenkei Blanche Hartman is being installed as Abbess of Zen Center in the traditional Mountain Seat Ceremony. She w ill be joining Abbots Sojun Mel Weitsman and Zoketsu Norman Fischer in the spiritual leadership of the community. The next issue of Wind Bell will feature coverage of this event. The kaisando altar at Tossajara UNDERSTANDING ORDINARY MIND IS BUDDHA Shunryu Suzuki Roshi May 1969 The point of my talk is just to give you some help in your practice. So it is just help. As I always say, there is no need for you to remember what I said as something definite. -

Essays of Kodo Sawaki

In the Spring of 2004 I was 22 years old. I lived at the San Francisco Zen Center with my teacher Kosho McCall, who at the time was receiving Dharma Transmission from Blanche Hartman. Blanche studied o-kesa sewing with Rev. Joshin Kasai, a disciple of Kōdō Sawaki Roshi. Blanche shared her appreciation for Sawaki’s teaching style with Kosho, and Kosho shared his appreciation of Sawaki with me. In 1990, Soto-Shu Shumucho published “The Zen Teachings of Homeless Kōdō,” Shohaku Okamura’s English translation of Kosho Uchiyama’s 1975 "Yadonashi Hokkusan." For the next ten years, that slim volume was about all there was in English by or about Sawaki Roshi. In the 90s, Association Zen Internationale published a magazine called “Zen Revue.” The first half was in French, and then it would repeat itself (sans photos) in English. I was very excited when I found several issues of this magazine in the reading room at City Center. Being a recently retired punk rocker, I felt compelled to make a fanzine. I spent a glorious day in the City Center copy room amongst boxes of back issues of “Wind Bell.” I felt nervous about being caught as I cut and pasted away while I was supposed to be working. The only person who saw me was Blanche’s husband Lou who asked what I was up to. I told him I was making a Homeless Kōdō magazine for Blanche and Kosho and he said, “far out.” The bits in the second portion of the zine are what was available on the Antai-ji webpage at the time.