Preaching to an Alien Culture: Resources in the Corinthian Letters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Epiphany of Our Lord Byzantine Catholic Church Montgomery

(Continued from a preceding page.) In the Liturgy we pray “for those who serve series produced by OLTV and Eastern Chris- and have served in this holy church.” Christ is among us! Epiphany of Our Lord tian Publications are heard daily as well as For now, we still need men and women to help with liturgy setup and takedown. (Christos posred’i nas!) Byzantine Catholic Church “Light of the East,” featuring Father Thomas Loya. The signup sheet for November & December is available on the information table. He is and shall be! Eastern Catholic Radio is a production of (Jest'i budet!) Eastern Catholic Broadcasting, a media Apos- Thank you! tolate affiliated with the Byzantine Catholic Eparchy of Passaic. With the permission of Bishop Kurt Burnette, the apostolate was easiest way to listen to Eastern Catholic Radio founded in 2014 at Saint Joseph Byzantine is through the free Live365 app or on your com- ◼ Catholic Church in New Brunswick, N.J., and puter or smartphone at www.easterncatholic — Today’s Divine Liturgy intention is offered for the blessed re- Saints Peter and Paul Byzantine Catholic broadcasting.com or Live365.com. Church in Somerset, N.J., by Father Francis pose of Jim Siemucha by Lou and Marie Shanks. ◼ Food Pantry — Our Mission Community’s Rella. Vičnaja jemu pamjať. ministry to the unfortunate of our area “And God will wipe away every tear from their eyes, there shall be The ministry began as weekly broadcasts Montgomery County through the local Food Pantry program, ad- no more death, nor sorrow, nor crying. There shall be no more of the Sunday Divine Liturgy and the produc- pain, for the former things have passed away.” Mission ministered by St. -

Sunday, November 10Th—2013 8Th Sunday of St. Luke SAINT SOPHIA

Sunday, November 10th—2013 8th Sunday of St. Luke HYMNS AT THE SMALL ENTRANCE (pg 7) Εὐφραινέσθω τὰ οὐράνια, First Antiphon (pg 4) Resurrectional Apolytikion Bless the Lord, O my soul, and Let the Heavens rejoice; let earthly things ἀγαλλιάσθω τὰ ἐπίγεια, ὅτι all that is within me be glad; for the Lord hath wrought might ἐποίησε κράτος, ἐν βραχίονι αὐτοῦ, ὁ Κύριος, ἐπάτησε τῷ bless His holy Name. with His arm, He hath trampled upon θανάτῳ τὸν θάνατον, Bless the Lord, O my soul, and death by death. The first-born of the dead πρωτότοκος τῶν νεκρῶν for g e t no t a ll th a t hath He become. From the belly of Hades ἐγένετο, ἐκ κοιλίας ᾅδου He has done for you. hath He delivered us, and hath granted ἐρρύσατο ἡμᾶς, καὶ παρέσχε τῷ The Lord in heaven has prepared κόσμῳ τὸ μέγα ἔλεος. His throne, and His kingdom great mercy to the world. rules over all. —— Troparian of Saint Sophia—Holy Wisdom of God Εὐλογητὸς εἶ Χριστὲ ὁ Θεὸς Second Antiphon (pg 5) Blessed are You O Christ our God, Who as ἡμῶν, ὁ πανσόφους τοὺς ἁλιεῖς Praise the Lord, O my soul; all wise the fishermen You showed forth; ἀναδείξας, καταπέμψας αὐτοῖς I will praise the Lord in my life; By sending your Holy Spirit down upon τὸ Πνεῦμα τὸ Ἅγιον, καὶ δι' I will chant unto my God them and through them the universe You αὐτῶν τὴν οἰκουμένην σαγηνεύσας, Φιλάνθρωπε, δόξα for as long as I have my being. drew unto your net. -

2 Thessalonians Introductory Handout

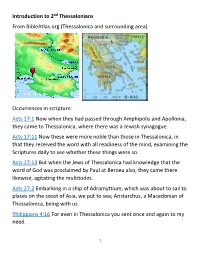

Introduction to 2nd Thessalonians From BibleAtlas.org (Thessalonica and surrounding area) Occurrences in scripture: Acts 17:1 Now when they had passed through Amphipolis and Apollonia, they came to Thessalonica, where there was a Jewish synagogue. Acts 17:11 Now these were more noble than those in Thessalonica, in that they received the word with all readiness of the mind, examining the Scriptures daily to see whether these things were so. Acts 17:13 But when the Jews of Thessalonica had knowledge that the word of God was proclaimed by Paul at Beroea also, they came there likewise, agitating the multitudes. Acts 27:2 Embarking in a ship of Adramyttium, which was about to sail to places on the coast of Asia, we put to sea; Aristarchus, a Macedonian of Thessalonica, being with us. Philippians 4:16 For even in Thessalonica you sent once and again to my need. 1 2 Timothy 4:10 for Demas left me, having loved this present world, and went to Thessalonica; Crescens to Galatia, and Titus to Dalmatia. From the International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: THESSALONICA thes-a-lo-ni'-ka (Thessalonike, ethnic Thessalonikeus): 1. Position and Name: One of the chief towns of Macedonia from Hellenistic times down to the present day. It lies in 40 degrees 40 minutes North latitude, and 22 degrees 50 minutes East longitude, at the northernmost point of the Thermaic Gulf (Gulf of Salonica), a short distance to the East of the mouth of the Axius (Vardar). It is usually maintained that the earlier name of Thessalonica was Therma or Therme, a town mentioned both by Herodotus (vii.121;, 179;) and by Thucydides (i0.61; ii.29), but that its chief importance dates from about 315 B.C., when the Macedonian king Cassander, son of Antipater, enlarged and strengthened it by concentrating there the population of a number of neighboring towns and villages, and renamed it after his wife Thessalonica, daughter of Philip II and step-sister of Alexander the Great. -

Sunday of Thomas the Apostle Called “The Twin”

Sunday, April 26, 2020 Sunday of Thomas the Apostle Called “The Twin” Hieromartyr Basil, bishop of Amasea with Venerable Glaphyra; Stephen, bishop of Perm; Venerable Ioanikios of Devitch in Serbia “Do not be unbelieving, but believing.” Archangel Gabriel Antiochian Orthodox Church A Parish of the Diocese of Miami and the Southeast His Eminence Met. JOSEPH, Archbishop of New York and Metropolitan of all North America His Grace Bishop NICHOLAS, Auxiliary Bishop of the Diocese of Miami and the Southeast Rev. Fr. Stephen De Young – Pastor 1237 Eraste Landry Rd. [email protected] Lafayette, LA 70506 (304) 444-6708 stgabriellafayette.org A Warm Welcome To Our Service Times Sunday Visitors! We are happy that you have joined us today! Matins – 9:00 AM Please join us for coffee after Divine Liturgy. It is Divine Liturgy – 10:00 AM our pleasure to have you in our presence this morning and we wish God’s Blessings to all who Monday visit with us today and hope you stop in again soon! Orthros – 9:00 AM If you have any questions in regards to our worship or Orthodoxy, please see Fr. Stephen and Wednesday he will gladly answer any of your questions to the Vespers – 6:00 PM best of his ability. Only Orthodox Christians may receive the Eucharist (Holy Communion) in the Orthodox Saturday Church. You may venerate the cross and take Great Vespers – 6:00 PM some of the blessed bread at the conclusion of Liturgy. Weekly Church Calendar (with fasting days) Sun. April 26 Mon. April 27 Tues. April 28 Weds. -

Weekly Schedule

Assumption of the Holy Virgin Orthodox Church 2101 South 28th St. (corner of 28th St. & Snyder Ave.) Philadelphia, PA 19145 * Church Phone: (215) 468-3535 Website: http://www.holyassumptionphilly.org http://www.facebook.com/holyassumptionphilly Mailing Address: PO Box 20083 * Point Breeze Station | Philadelphia PA 19145-0383 Sunday, November 10, 2019 | 21st Sunday After Pentecost Tone 4 – Apostles of the Seventy: Erastus, Olympas, Herodion Sosipater, Quartus and Tertius and their companions (1st c.) Martyr Orestes of Cappadocia (204) V. Rev. Mark W Koczak, Rector 615 West 11th Street | New Castle, DE 19720-6020 Phone: Home: 302.322.0943 | Mobile: 302.547.4952 Email: [email protected] Deacon – Michael McCartney Parish President - Matthew Andrews Phone: 856.217.8075 Weekly Schedule Today: St. Herman’s of Alaska Food Festival – 12PM to 4PM Today: Happy 244th Birthday to the United States Marine Corp. Friday: Beginning of the Nativity (St Phillip’s) Fast ADVENT FAST BEGINS! Saturday: November 16 - Great Vespers at 4:00PM! Sunday: November 17 – Saint Gregory the Wonderworker Reading of Hours – 9:30am Divine Liturgy – 10:00am Fellowship & coffee hour to follow the Divine Liturgy Sunday: November 17 – A Very Brief Property Committee Meeting will be held in the church basement. [NOTE CHANGE OF DATE] Sunday: November 17 – Parish Council Meeting after Divine Liturgy. Meeting to discuss the 5-year Strategic Planning for the parish. Tuesday: November 19 - Bible Study at 6:30pm in the church basement. [NOTE CHANGE OF DATE] 1 Texts for the Liturgical -

Euchology: a Manual of Prayers of the Holy Ortho- Dox Church

Euchology: A Manual of Prayers of the Holy Ortho- dox Church Author(s): Shann, G. V. Publisher: CCEL i Contents Euchology 1 Initial Stuff 1 PREFACE 2 ii This PDF file is from the Christian Classics Ethereal Library, www.ccel.org. The mission of the CCEL is to make classic Christian books available to the world. • This book is available in PDF, HTML, and other formats. See http://www.ccel.org/ccel/shann/euchology.html. • Discuss this book online at http://www.ccel.org/node/3480. The CCEL makes CDs of classic Christian literature available around the world through the Web and through CDs. We have distributed thousands of such CDs free in developing countries. If you are in a developing country and would like to receive a free CD, please send a request by email to [email protected]. The Christian Classics Ethereal Library is a self supporting non-profit organization at Calvin College. If you wish to give of your time or money to support the CCEL, please visit http://www.ccel.org/give. This PDF file is copyrighted by the Christian Classics Ethereal Library. It may be freely copied for non-commercial purposes as long as it is not modified. All other rights are re- served. Written permission is required for commercial use. iii Euchology InitialEuchology Stuff EUCHOLOGY A MANUAL OF PRAYERS OF THE HOLY ORTHODOX CHURCH DONE INTO ENGLISH By G. V. SHANN. AMS PRESS Reprinted from the edition of 1891, Kidderminster First AMS EDITION published 1969 Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number: 75-82260 AMS PRESS INC TO THE VERY REVEREND, THE ARCHPRIEST EUGENE SMIRNOFF, CHAPLAIN TO THE IMPERIAL RUSSIAN EMBASSY IN LONDON, THIS EUCHOLOGY IS GRATEFULLY INSCRIBED BY THE TRANSLATOR. -

1 Thessalonians

"Scripture taken from the NEW AMERICAN STANDARD BIBLE®, © Copyright 1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995 by The Lockman Foundation Used by permission." (www.Lockman.org) 1 Thessalonians Background To Epistle 1. Paul went to Macedonia in response to the Macedonia call. (Acts 16:9-12). ACT 16:9 And a vision appeared to Paul in the night: a certain man of Macedonia was standing and appealing to him, and saying, "Come over to Macedonia and help us." ACT 16:10 And when he had seen the vision, immediately we sought to go into Macedonia, concluding that God had called us to preach the gospel to them. ACT 16:11Therefore putting out to sea from Troas, we ran a straight course to Samothrace, and on the day following to Neapolis; ACT 16:12 and from there to Philippi, which is a leading city of the district of Macedonia, a Roman colony; and we were staying in this city for some days. 2. He came first to Philippi in Macedonia where he had some success. See “my joy and crown” - Phil. 3:1. a. He converted Lydia and her family. (Acts 16:13-15). Both she and “her household” were baptized after Paul produced saving faith in them through the preaching of the gospel. (Acts 16:15). b. He and Silas were then cast into jail because they cast a spirit of divination from a slave girl. (Acts 16:16:16-24). c. While in jail he converted the jailer and his family through “the word of the Lord” [the gospel]. -

"Lord I Call..." – Tone 4 Reader: in the Fourth Tone, Lord, I Call Upon

"Lord I Call..." – Tone 4 Reader: In the Fourth Tone, Lord, I call upon You, hear me! Lord, I call upon You, hear me! Let my prayer arise Hear me, O Lord! in Your sight as incense, Lord, I call upon You, hear me! and let the lifting up of my hands Receive the voice of my prayer, be an evening sacrifice!// when I call upon You!// Hear me, O Lord! Hear me, O Lord! Reader: (Reads text from service book) v. (10) Bring my soul out of prison, that I may give thanks to Your name! We glorify Your Resurrection on the third day, O Christ God, by always honoring Your life-creating Cross; by it You have renewed the corrupted nature of mankind, O almighty One. By it You have renewed our entrance to heaven,// for You are good and the Lover of mankind. v. (9) The righteous will surround me; for You will deal bountifully with me. You loosed the Tree's verdict of disobedience, O Savior, by being voluntarily nailed to the tree of the Cross. By descending to hell, O almighty God, You broke the bonds of death. Therefore, we adore Your Resurrection from the dead, singing in joy:// “Glory to You, O all powerful Lord!” v. (8) Out of the depths I cry to You, O Lord. Lord, hear my voice! You smashed the gates of hell, O Lord, and by Your death You demolished the kingdom of death. You delivered the human race from corruption,// granting the world life, incorruption and great mercy. -

A Chronology of the Apostle Paul

Dr. J. Paul Tanner Pauline Chronology Page 1 A CHRONOLOGY OF THE APOSTLE PAUL J.Paul Tanner,ThM,PhD 2nd Edition:February25,2003 INTRODUCTION Any attempt toreconstruct a chronology for the events inthe life of Paul must admit to some degree of approximation, thoughwe can"come close" todating certainaspects of the Apostle's life. Inreviewing the scholarship of others,twokeydecisions have strong bearing onmost everything else.The first is the date that one presumes for the crucifixion of Christ. For the purposes of this study, I will follow the commendable work of HaroldHoehner,anduse the date of AD 33for our Lord's death. 1 The secondis the date of Paul's ministry at Corinth. Acts 18:12 mentions that Paul was brought before Gallio who was proconsul of Achaia (lower Greece). The year of his office was from early summer of AD 51 to early summer of AD 52. Thus,Paul's stay inCorinthhadto overlap with the administrationof Gallio. Although most scholars agree onthis date for Gallio,they differ over the exact years that Paul was inCorinth. Had Paul recently arrived in Corinth when Gallio took office, or was he already near the conclusion of his Corinthianministry (which lastedat least 18months − Acts 18:11)? Hence,some will date Paul's arrival in Corinthas early as Dec AD 49,while others will date it inthe spring of AD 51. Most attempts toreconstruct a chronology for Paul's life will be made as a result of working backward and forward from the date of Paul'stimeinCorinth.Thisaccountsfora slightdifferenceof ayearortwoinmostschemes. Inevitably,one must alsomake certainassumptions oncertain other matters. -

Raising the Son of the Widow of Nain the Training of Paul

RAISING THE SON OF THE WIDOW OF NAIN THE TRAINING OF PAUL October 10, 2010 3rd Sunday of Luke Revision E GOSPEL: Luke 7:11-16 EPISTLE: Galatians 1:11-19 Today’s Gospel lesson is used in the West at about this same time of year for the 26th Sunday after Trinity or sometimes for the 3rd Sunday after Pentecost. GOSPEL LESSON: Luke 7:11-16 Whereas many of the accounts of events in Jesus’ life are recorded in several, if not all four, of the Gospel accounts, today’s lesson is recorded only by Luke. The setting for this event is early in the second year of Jesus’ public ministry. Jesus had just finished the “Sermon on the Mount” (Matthew 5:1-7:29) and the “Sermon on the Plain” (so called from Luke 6:17) shortly thereafter (Luke 6:17-49). The Twelve Apostles have been selected by Jesus, (Luke 6:12-16) but have not yet been sent out two-by-two to heal the sick and cast out demons (Luke 9:1-6). John the Baptist had been imprisoned (Luke 7:18-23) but not yet beheaded by Herod (Luke 9:7-9). Shortly after this Gospel account, John the Baptist’s disciples came to Jesus and asked if He was the One to come or if they should look for another. Jesus replied that they should look around, for the blind see, the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised and the poor have the Gospel preached to them. -

Greek Orthodox Bible : New Testament

THE EASTERN - GREEK ORTHODOX BIBLE : NEW TESTAMENT Presented to Presented by Date – Occasion THE EASTERN - GREEK ORTHODOX BIBLE NEW TESTAMENT THE EASTERN / GREEK ORTHODOX BIBLE BASED ON THE SEPTUAGINT AND THE PATRIARCHAL TEXT NEW TESTAMENT ALSO KNOWN AS THE CHRISTIAN GREEK SCRIPTURES With extensive introductory and supplemental material The EOB New Testament is presented in memory of Archbishop Vsevolod of Scopelos (†2007) Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the USA Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople And in honor of His Beatitude Metropolitan Jonah Primate of the Orthodox Church in America ABBREVIATIONS AND CODES Indicates words added for clarity and accuracy but which may not [ ] be in the Greek text. For public reading, these words can be included or skipped Indicates words added for theological clarity and accuracy. For { } public reading, these words should be skipped Indicates words that may have been added in the Byzantine textual tradition for the purpose of clarification, harmonization or liturgical < > use and which are present in the PT, but which may not have been part of the original manuscripts ANF/PNF Ante-Nicene Fathers / Post-Nicene Fathers BAC Being as Communion, John Zizioulas CCC Catechism of the Catholic Church Modern “eclectic” texts or reconstructed "critical texts" (United CT Bible Societies Text (UBS) or the Nestle-Aland Text (NA)) CTC Called to Communion, Joseph Ratzinger EBC Eucharist, Bishop, Church, John Zizioulas EOB Eastern / Greek Orthodox Bible HBB His Broken Body, Laurent Cleenewerck HE Ecclesiastical History (Eusebius) (Paul Maier’s edition) KJV King James Version (sometimes called Authorized Version) Greek translation of the Old Testament known as the Septuagint LXX which is the basis for the main English text of the EOB/OT TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTORY SECTION ABBREVIATIONS AND CODES .............................................................................. -

Romans (16:21-27) It Is Finished Part 101 – April 8, 2007

Romans (16:21-27) It is Finished Part 101 – April 8, 2007 PAUL’S PALS Paul is in Corinth, making final preparations for his trip to Jerusalem with the Gentile offering for poverty-stricken Jews. As he finalizes this letter, delegates from various churches (who’ll accompany him to Jerusalem), have begun to arrive. And they send their greetings through Paul, to Rome. Timothy, my fellow worker, sends his greetings to you, as do Lucius, Jason and Sosipater, my relatives. I, Tertius, who wrote down this letter, greet you in the Lord. Gaius, whose hospitality I and the whole church here enjoy, sends you his greetings. Erastus, who is the city’s director of public works, and our brother Quartus send you their greetings. - Romans 16:21-23 NIV “Timothy” was like a son to Paul. “First Timothy” and “Second Timothy” are both NT books taken from letters Paul sent him. Timothy, “Lucius”, “Jason”, and “Sosipater” are all fellow-Jews, that’s why Paul calls them: “my relatives”. This is most-likely the “Jason” whose house was mobbed, and he was attacked for letting Paul stay with him in Thessalonica. [The mob] rushed to Jason’s house in search of Paul and Silas … But when they did not find them, they dragged Jason and some other brothers before the city officials, shouting: “These men who have caused trouble all over the world have now come here, and Jason has welcomed them into his house. They are all … saying that there is another king, one called Jesus. - Acts 17:5-7 NIV Paul probably had poor eyesight, so he dictates to a scribe: I, Tertius, who wrote down this letter, greet you in the Lord Very gracious of Paul, and uncharacteristic of the time, to let the secretary say hello; he was most likely a fellow believer.