А. Мalikov Palacky University Olomouc Olomouc, Czech Republic [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selected Works of Chokan Valikhanov Selected Works of Chokan Valikhanov

SELECTED WORKS OF CHOKAN VALIKHANOV CHOKAN OF WORKS SELECTED SELECTED WORKS OF CHOKAN VALIKHANOV Pioneering Ethnographer and Historian of the Great Steppe When Chokan Valikhanov died of tuberculosis in 1865, aged only 29, the Russian academician Nikolai Veselovsky described his short life as ‘a meteor flashing across the field of oriental studies’. Set against his remarkable output of official reports, articles and research into the history, culture and ethnology of Central Asia, and more important, his Kazakh people, it remains an entirely appropriate accolade. Born in 1835 into a wealthy and powerful Kazakh clan, he was one of the first ‘people of the steppe’ to receive a Russian education and military training. Soon after graduating from Siberian Cadet Corps at Omsk, he was taking part in reconnaissance missions deep into regions of Central Asia that had seldom been visited by outsiders. His famous mission to Kashgar in Chinese Turkestan, which began in June 1858 and lasted for more than a year, saw him in disguise as a Tashkent mer- chant, risking his life to gather vital information not just on current events, but also on the ethnic make-up, geography, flora and fauna of this unknown region. Journeys to Kuldzha, to Issyk-Kol and to other remote and unmapped places quickly established his reputation, even though he al- ways remained inorodets – an outsider to the Russian establishment. Nonetheless, he was elected to membership of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society and spent time in St Petersburg, where he was given a private audience by the Tsar. Wherever he went he made his mark, striking up strong and lasting friendships with the likes of the great Russian explorer and geographer Pyotr Petrovich Semyonov-Tian-Shansky and the writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky. -

From the Editorial Board

https://doi.org/10.7592/FEJF2019.76.kazakh FROM THE EDITORIAL BOARD KAZAKH DIASPORA IN KYRGYZSTAN: HISTORY OF SETTLEMENT AND ETHNOGRAPHIC PECULIARITIES Bibiziya Kalshabayeva Professor, Department of History, Archeology and Ethnology Al-Farabi Kazakh National University Almaty, Kazakhstan Email: [email protected] Gulnara Dadabayeva Associate Professor, KIMEP University Almaty, Kazakhstan Email: [email protected] Dauren Eskekbaev Associate Professor, Almaty University of Management Almaty, Kazakhstan Email: [email protected] Abstract: The article focuses on the most significant stages of the formation of the Kazakh diaspora in the Kyrgyz Republic, to point out what reasons contributed to the rugged Kazakh migration process in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and how it affected the forms and types of their settlements (compact or disperse). The researched issues also include the identification of factors provoked by humans and the state to launch these migrations. Surprisingly enough, opposite to the claims made by independent Kazakhstan leadership in the early 2000s, the number of Kazakhs in Kyrgyzstan wishing to become repatriates to their native country is still far from the desired. Thus the article is an attempt to find out what reasons and factors influence the Kazakh residents’ desire to stay in the neighboring country as a minority. To provide the answer, the authors analyzed the dynamics of statistical variations in the number of migrants and the reasons of these changes. The other key point in tracing what characteristic features separate Kazakhs in Kyrgyzstan and their kinsmen in Kazakhstan is the archival data, statistical, historical, and field sources, which provide a systematic overview of the largely unstudied pages of the history of the Kazakh diaspora. -

ASTRA Salvensis, Supplement No. 1/2021 173 the ROLE OF

ASTRA Salvensis, Supplement no. 1/2021 THE ROLE OF ULUSES AND ZHUZES IN THE FORMATION OF THE ETHNIC TERRITORY OF THE KAZAKH PEOPLE Aidana KOPTILEUOVA1, Bolat KUMEKOV1, Meiramkul T. BIZHANOVA2 1Department of Eurasian Studies, L.N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University, Nur-Sultan, Republic of Kazakhstan 2Department of History of Kazakhstan, Al-Farabi Kazakh National University, Almaty, Republic of Kazakhstan Abstract: The article is devoted to one of the pressing issues of Kazakh historiography – the problems of the formation of the ethnic territory of the Kazakh people. The ethnic territory of the Kazakh people is the national borders of today’s Republic of Kazakhstan, inherited from the nomadic ancestors – the Kazakh Khanate. Uluses are a distinctive feature of the social structure of nomads, Zhuzes are one of the Kazakh nomads. In this regard, our goal is to determine their role in shaping the ethnic territory of the Kazakh people. To do this, a comparative analysis will be made according to different data and historiographic materials, in addition, the article will cover the issues of the appearance of the zhuzes system in Kazakh society and its stages. As a result of this work, the authorial offers are proposed – the hypothesis of the gradual formation of the ethnic territory and the Kazakh zhuzes system. Keywords: Kazakh historiography, Middle ages, the Mongol period, Kazakh Khanate, gradual formation. The formation of the ethnic territory of the Kazakh people is closely connected not only with the political events of the period under review, but with ethnic processes. Kazakhs consist of many clans and tribes that have their hereditary clan territories. -

Review the Legacy of Nomadic Empires in Steppe Landscapes Of

ISSN 10193316, Herald of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 2009, Vol. 79, No. 5, pp. 473–479. © Pleiades Publishing, Ltd., 2009. Original Russian Text © A.A. Chibilev, S.V. Bogdanov, 2009, published in Vestnik Rossiiskoi Akademii Nauk, 2009, Vol. 79, No. 9, pp. 823–830. Review Information about the impact of nomadic peoples on the landscapes of the steppe zone of northern Eurasia in the 18th–19th centuries is generalized against a wide historical–geographical background, and the objec tives of a new scientific discipline, historical steppe studies, are substantiated. DOI: 10.1134/S1019331609050104 The Legacy of Nomadic Empires in Steppe Landscapes of Northern Eurasia A. A. Chibilev and S. V. Bogdanov* The steppe landscape zone covering more than settlements with groundbased or earthsheltered 8000 km from east to west has played an important role homes were situated close to fishing areas, watering in the history of Russia and, ultimately, the Old World places, and migration paths of wild ungulates. Steppe for many centuries. The ethnogenesis of many peoples bioresources were used extremely selectively. of northern Eurasia is associated with the historical– Nomadic peoples affected the steppe everywhere. The geographical space of the steppes. The continent’s nomadic, as opposed to semisedentary, lifestyle steppe and forest–steppe vistas became the cradle of implies a higher development of the territory. The nomadic cattle breeding in the early Bronze Age (from zone of economic use includes the whole nomadic the 5th through the early 2nd millennium B.C.). By area. Owing to this, nomads had an original classifica the 4th millennium B.C., horses and cattle were pre tion of its parts with regard to their suitability for set dominantly bred in northern Eurasia. -

Thesis Approval Form Nazarbayev University School of Sciences and Humanities

THESIS APPROVAL FORM NAZARBAYEV UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF SCIENCES AND HUMANITIES NATION BRANDING: AN INSTRUMENT OF SOFT POWER OR NATION-BUILDING? THE CASE OF KAZAKHSTAN ҰЛТТЫҚ БРЕНДИНГ: ЖҰМСАҚ ҚУАТ НЕ ҰЛТ-ҚҰРЫЛЫС ҚҰРЫЛҒЫСЫ? ҚАЗАҚСТАН ҮЛГІСІ НАЦИОНАЛЬНЫЙ БРЕНДИНГ: ИНСТРУМЕНТ МЯГКОЙ СИЛЫ ИЛИ НАЦИОНАЛЬНОЕ СТРОИТЕЛЬСТВО? ПРИМЕР КАЗАХСТАНА BY Leila Ramankulova APPROVED BY DR. Neil Collins ON 3rd May of 2020 _________________________________________ Signature of Principal Thesis Adviser In Agreement with Thesis Advisory Committee Second Reader: Dr. Spencer L Willardson External Reviewer: Dr. Phil Harris NATION BRANDING: AN INSTRUMENT OF SOFT POWER OR NATION-BUILDING? THE CASE OF KAZAKHSTAN ҰЛТТЫҚ БРЕНДИНГ: ЖҰМСАҚ ҚУАТ НЕ ҰЛТ-ҚҰРЫЛЫС ҚҰРЫЛҒЫСЫ? ҚАЗАҚСТАН ҮЛГІСІ НАЦИОНАЛЬНЫЙ БРЕНДИНГ: ИНСТРУМЕНТ МЯГКОЙ СИЛЫ ИЛИ НАЦИОНАЛЬНОЕ СТРОИТЕЛЬСТВО? ПРИМЕР КАЗАХСТАНА by Leila Ramankulova A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Political Science and International Relations at NAZARBAYEV UNIVERSITY - SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCE 2020 © 2020 LEILA RAMANKULOVA All Rights Reserved NATION BRANDING: AN INSTRUMENT OF SOFT POWER OR NATION-BUILDING? THE CASE OF KAZAKHSTAN ҰЛТТЫҚ БРЕНДИНГ: ЖҰМСАҚ ҚУАТ НЕ ҰЛТ-ҚҰРЫЛЫС ҚҰРЫЛҒЫСЫ? ҚАЗАҚСТАН ҮЛГІСІ НАЦИОНАЛЬНЫЙ БРЕНДИНГ: ИНСТРУМЕНТ МЯГКОЙ СИЛЫ ИЛИ НАЦИОНАЛЬНОЕ СТРОИТЕЛЬСТВО? ПРИМЕР КАЗАХСТАНА by Leila Ramankulova Principal Adviser: Dr. Neil Collins Second Reader: Dr. Spencer L Willardson External Reviewer: Dr. Phil Harris Electronic Version Approved: Dr. Caress Schenk Director of the MA Program in Political Science and International Relations School of Humanities and Social Sciences Nazarbayev University May 2020 v Abstract Nation branding is a process by which countries seek to create an attractive image and manipulate its external perception. The process of branding a nation involves a broad array of activities from an advertisement on TV and journals to much more extensive public diplomacy initiatives. -

The Northern Black Sea Region in Classical Antiquity 4

The Northern Black Sea Region by Kerstin Susanne Jobst In historical studies, the Black Sea region is viewed as a separate historical region which has been shaped in particular by vast migration and acculturation processes. Another prominent feature of the region's history is the great diversity of religions and cultures which existed there up to the 20th century. The region is understood as a complex interwoven entity. This article focuses on the northern Black Sea region, which in the present day is primarily inhabited by Slavic people. Most of this region currently belongs to Ukraine, which has been an independent state since 1991. It consists primarily of the former imperial Russian administrative province of Novorossiia (not including Bessarabia, which for a time was administered as part of Novorossiia) and the Crimean Peninsula, including the adjoining areas to the north. The article also discusses how the region, which has been inhabited by Scythians, Sarmatians, Greeks, Romans, Goths, Huns, Khazars, Italians, Tatars, East Slavs and others, fitted into broader geographical and political contexts. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. Space of Myths and Legends 3. The Northern Black Sea Region in Classical Antiquity 4. From the Khazar Empire to the Crimean Khanate and the Ottomans 5. Russian Rule: The Region as Novorossiia 6. World War, Revolutions and Soviet Rule 7. From the Second World War until the End of the Soviet Union 8. Summary and Future Perspective 9. Appendix 1. Sources 2. Literature 3. Notes Indices Citation Introduction -

Zhanat Kundakbayeva the HISTORY of KAZAKHSTAN FROM

MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND SCIENCE OF THE REPUBLIC OF KAZAKHSTAN THE AL-FARABI KAZAKH NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Zhanat Kundakbayeva THE HISTORY OF KAZAKHSTAN FROM EARLIEST PERIOD TO PRESENT TIME VOLUME I FROM EARLIEST PERIOD TO 1991 Almaty "Кazakh University" 2016 ББК 63.2 (3) К 88 Recommended for publication by Academic Council of the al-Faraby Kazakh National University’s History, Ethnology and Archeology Faculty and the decision of the Editorial-Publishing Council R e v i e w e r s: doctor of historical sciences, professor G.Habizhanova, doctor of historical sciences, B. Zhanguttin, doctor of historical sciences, professor K. Alimgazinov Kundakbayeva Zh. K 88 The History of Kazakhstan from the Earliest Period to Present time. Volume I: from Earliest period to 1991. Textbook. – Almaty: "Кazakh University", 2016. - &&&& p. ISBN 978-601-247-347-6 In first volume of the History of Kazakhstan for the students of non-historical specialties has been provided extensive materials on the history of present-day territory of Kazakhstan from the earliest period to 1991. Here found their reflection both recent developments on Kazakhstan history studies, primary sources evidences, teaching materials, control questions that help students understand better the course. Many of the disputable issues of the times are given in the historiographical view. The textbook is designed for students, teachers, undergraduates, and all, who are interested in the history of the Kazakhstan. ББК 63.3(5Каз)я72 ISBN 978-601-247-347-6 © Kundakbayeva Zhanat, 2016 © al-Faraby KazNU, 2016 INTRODUCTION Данное учебное пособие is intended to be a generally understandable and clearly organized outline of historical processes taken place on the present day territory of Kazakhstan since pre-historic time. -

Chinese Historian Su Beihai's Manuscript About the History Of

UDC 908 Вестник СПбГУ. Востоковедение и африканистика. 2020. Т. 12. Вып. 4 Chinese Historian Su Beihai’s Manuscript about the History of Kazakh People in Central Asia: Historical and Source Study Analysis* T. Z. Kaiyrken, D. A. Makhat, A. Kadyskyzy L. N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University, 2, ul. Satpayeva, Nur-Sultan, 010008, Kazakhstan For citation: Kaiyrken T. Z., Makhat D. A., Kadyskyzy A. Chinese Historian Su Beihai’s Manuscript about the History of Kazakh People in Central Asia: Historical and Source Study Analysis. Vestnik of Saint Petersburg University. Asian and African Studies, 2020, vol. 12, issue 4, pp. 556–572. https://doi.org/10.21638/spbu13.2020.406 The article analyses the research work of Chinese scientist Su Beihai on Kazakh history, one of the oldest nationalities in Eurasia. This work has been preserved as a manuscript and its main merit is the study of Kazakh history from early times to the present. Moreover, it shows Chinese scientists’ attitude to Kazakh history. Su Beihai’s scientific analysis was writ- ten in the late 1980s in China. At that time, Kazakhstan was not yet an independent country. Su Beihai drew on various works, on his distant expedition materials and demonstrated with facts that Kazakh people living in their modern settlements have a 2,500-year history. Although the book was written in accordance with the principles of Chinese communist historiography, Chinese censorship prevented its publication. Today, Kazakh scientists are approaching the end of their study and translation of Su Beihai’s manuscript. Therefore, the article first analyses the most important and innovative aspects of this work for Kazakh history. -

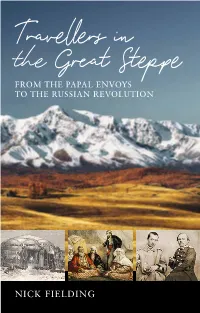

Nick Fielding

Travellers in the Great Steppe FROM THE PAPAL ENVOYS TO THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION NICK FIELDING “In writing this book I have tried to explain some of the historical events that have affected those living in the Great Steppe – not an easy task, as there is little study of this subject in the English language. And the disputes between the Russians and their neighbours and between the Bashkirs, the Kazakhs, the Turkomans, the Kyrgyz and the Kalmyks – not to mention the Djungars, the Dungans, the Nogai, the Mongols, the Uighurs and countless others – means that this is not a subject for the faint-hearted. Nonetheless, I hope that the writings referred to in this book have been put into the right historical context. The reasons why outsiders travelled to the Great Steppe varied over time and in themselves provide a different kind of history. Some of these travellers, particularly the women, have been forgotten by modern readers. Hopefully this book will stimulate you the reader to track down some of the long- forgotten classics mentioned within. Personally, I do not think the steppe culture described so vividly by travellers in these pages will ever fully disappear. The steppe is truly vast and can swallow whole cities with ease. Landscape has a close relationship with culture – and the former usually dominates the latter. Whatever happens, it will be many years before the Great Steppe finally gives up all its secrets. This book aims to provide just a glimpse of some of them.” From the author’s introduction. TRAVELLERS IN THE GREAT STEPPE For my fair Rosamund TRAVELLERS IN THE GREAT STEPPE From the Papal Envoys to the Russian Revolution NICK FIELDING SIGNAL BOOKS . -

Central Asia, August 2002

Description of document: US Department of State Self Study Guide for Central Asia, August 2002 Requested date: 11-March-2007 Released date: 25-Mar-2010 Posted date: 19-April-2010 Source of document: Freedom of Information Act Office of Information Programs and Services A/GIS/IPS/RL U. S. Department of State Washington, D. C. 20522-8100 Fax: 202-261-8579 Note: This is one of a series of self-study guides for a country or area, prepared for the use of USAID staff assigned to temporary duty in those countries. The guides are designed to allow individuals to familiarize themselves with the country or area in which they will be posted. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. -

Hijra and Forced Migration from Nineteenth-Century Russia to The

Cahiers du monde russe Russie - Empire russe - Union soviétique et États indépendants 41/1 | 2000 Varia Hijra and forced migration from nineteenth- century Russia to the Ottoman Empire A critical analysis of the Great Tatar emigration of 1860-1861 Brian Glyn Williams Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/monderusse/39 DOI: 10.4000/monderusse.39 ISSN: 1777-5388 Publisher Éditions de l’EHESS Printed version Date of publication: 1 January 2000 Number of pages: 79-108 ISBN: 2-7132-1353-3 ISSN: 1252-6576 Electronic reference Brian Glyn Williams, « Hijra and forced migration from nineteenth-century Russia to the Ottoman Empire », Cahiers du monde russe [Online], 41/1 | 2000, Online since 15 January 2007, Connection on 20 April 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/monderusse/39 ; DOI : 10.4000/monderusse.39 © École des hautes études en sciences sociales, Paris. BRIAN GLYN WILLIAMS HIJRA AND FORCED MIGRATION FROM NINETEENTH-CENTURY RUSSIA TO THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE A critical analysis of the Great Crimean Tatar emigration of 1860-1861 THE LARGEST EXAMPLES OF FORCED MIGRATIONS in Europe since the World War II era have involved the expulsion of Muslim ethnic groups from their homelands by Orthodox Slavs. Hundreds of thousands of Bulgarian Turks were expelled from Bulgaria by Todor Zhivkov’s communist regime during the late 1980s; hundreds of thousands of Bosniacs were cleansed from their lands by Republika Srbska forces in the mid-1990s; and, most recently, close to half a million Kosovar Muslims have been forced from their lands by Yugoslav forces in Kosovo in Spring of 1999. This process can be seen as a continuation of the “Great Retreat” of Muslim ethnies from the Balkans, Pontic rim and Caucasus related to the nineteenth-century collapse of Ottoman Muslim power in this region. -

Khanate of the Golden Horde (Kipchak)

The Mongol Catastrophe For the Muslim east, the sudden eruption of the Mongol hordes was an indescribable calamity. Something of the shock and despair of Muslim reaction can be seen in the history of the contemporary historian Ibn al-Athir (d. 1233). He writes here about the year 1220-1221 when the Mongols (“Tartars”) burst in on the eastern lands. Is this a positive, negative, or neutral description of the Mongols? Why might the Mongols be compared to Alexander rather than, say, the Huns? they eat, [needing] naught else. As for their beasts which they ride, these dig into I say, therefore, that this thing involves the description of the greatest catastrophe the earth with their hoofs and eat the roots of plants, knowing naught of barley. and the most dire calamity (of the like of which days and nights are innocent) And so, when they alight anywhere, they have need of nothing from without. As for which befell all men generally, and the Muslims in particular; so that, should 0e say their religion, the‟ worship the sun when it arises, and regard nothing as unlawful, that the world, since God Almighty created Adam until now, hath not been afflicted for the; eat all beasts, even dogs, pigs, and the like; nor do they recognise the with the like thereof, he would but speak the truth. For indeed history doth not marriage-tie, for several men are in marital relations with one woman, and if a child contain aught which approaches or comes nigh unto it.... is born, it knows not who is its father.