Virtual Tour of Maine's Fossils

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolutionary Patterns of Trilobites Across the End Ordovician Mass Extinction

Evolutionary Patterns of Trilobites Across the End Ordovician Mass Extinction by Curtis R. Congreve B.S., University of Rochester, 2006 M.S., University of Kansas, 2008 Submitted to the Department of Geology and the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Kansas in partial fulfillment on the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2012 Advisory Committee: ______________________________ Bruce Lieberman, Chair ______________________________ Paul Selden ______________________________ David Fowle ______________________________ Ed Wiley ______________________________ Xingong Li Defense Date: December 12, 2012 ii The Dissertation Committee for Curtis R. Congreve certifies that this is the approved Version of the following thesis: Evolutionary Patterns of Trilobites Across the End Ordovician Mass Extinction Advisory Committee: ______________________________ Bruce Lieberman, Chair ______________________________ Paul Selden ______________________________ David Fowle ______________________________ Ed Wiley ______________________________ Xingong Li Accepted: April 18, 2013 iii Abstract: The end Ordovician mass extinction is the second largest extinction event in the history or life and it is classically interpreted as being caused by a sudden and unstable icehouse during otherwise greenhouse conditions. The extinction occurred in two pulses, with a brief rise of a recovery fauna (Hirnantia fauna) between pulses. The extinction patterns of trilobites are studied in this thesis in order to better understand selectivity of the -

PROPERTY of Alabita STATE Geoloclcal Survlfl LBWY

PROPERTY OF ALABItA STATE GEOLOClCAL SURVLFl LBWY U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR TO ACCOMPANY MAP 1-1942 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEOLOGIC MAP AND FOLD- AND THRUST-BELT INTERPRETATION OF THE SOUTHEASTERN PART OF THE CHARLEY RlVER QUADRANGLE, EAST-CENTRAL ALASKA By James H. Dover INTRODUCTION The report contains a geologic map and interpretive cross sections (scale 1:100,000, sheets 1 and 2, respectively), This report presents the geologic map evidence for and a small-scale tectonic map showing regional structural the interpretation of the Charley River region as a fold and continuity and trends (scale 1:500,000, fig. sheet 2). thrust belt. Stratigraphic problems bearing on the rigor of 4, The geologic map contains considerable detail this interpretation are briefly reviewed, and some regional compiled from more than 1,000 field stations (fig. 1, tectonic implications of the fold and thrust belt sheet 1). Nearly 85 percent of these stations and their model-including the interaction of the fold and thrust belt included data are recompiled directly from the original field with the Tintina strike-slip fault zone, are also discussed. notes and field sheets (1960-63, 1967-68, 1973) of PREVIOUS WORK Brabb and Churkin. The new data were collected during parts of four field seasons, from 1982 to 1985, and Geologic observations were first made in the Charley involve a total of 25 days of helicopter-supported field River region by pioneering Alaskan geologists such work, concentrated largely in localities where pre-existing as Prindle (1905, 1906, 1913), Kindle (1908), Brooks data were scarce, or in localities judged from previous and Kindle (1908), and Cairnes (1914), but the recon- work to be critical to structural interpretation. -

Earliest Record of Megaphylls and Leafy Structures, and Their Initial Diversification

Review Geology August 2013 Vol.58 No.23: 27842793 doi: 10.1007/s11434-013-5799-x Earliest record of megaphylls and leafy structures, and their initial diversification HAO ShouGang* & XUE JinZhuang Key Laboratory of Orogenic Belts and Crustal Evolution, School of Earth and Space Sciences, Peking University, Beijing 100871, China Received January 14, 2013; accepted February 26, 2013; published online April 10, 2013 Evolutionary changes in the structure of leaves have had far-reaching effects on the anatomy and physiology of vascular plants, resulting in morphological diversity and species expansion. People have long been interested in the question of the nature of the morphology of early leaves and how they were attained. At least five lineages of euphyllophytes can be recognized among the Early Devonian fossil plants (Pragian age, ca. 410 Ma ago) of South China. Their different leaf precursors or “branch-leaf com- plexes” are believed to foreshadow true megaphylls with different venation patterns and configurations, indicating that multiple origins of megaphylls had occurred by the Early Devonian, much earlier than has previously been recognized. In addition to megaphylls in euphyllophytes, the laminate leaf-like appendages (sporophylls or bracts) occurred independently in several dis- tantly related Early Devonian plant lineages, probably as a response to ecological factors such as high atmospheric CO2 concen- trations. This is a typical example of convergent evolution in early plants. Early Devonian, euphyllophyte, megaphyll, leaf-like appendage, branch-leaf complex Citation: Hao S G, Xue J Z. Earliest record of megaphylls and leafy structures, and their initial diversification. Chin Sci Bull, 2013, 58: 27842793, doi: 10.1007/s11434- 013-5799-x The origin and evolution of leaves in vascular plants was phology and evolutionary diversification of early leaves of one of the most important evolutionary events affecting the basal euphyllophytes remain enigmatic. -

Innovations in Animal-Substrate Interactions Through Geologic Time

The other biodiversity record: Innovations in animal-substrate interactions through geologic time Luis A. Buatois, Dept. of Geological Sciences, University of Saskatchewan, 114 Science Place, Saskatoon SK S7N 5E2, Canada, luis. [email protected]; and M. Gabriela Mángano, Dept. of Geological Sciences, University of Saskatchewan, 114 Science Place, Saskatoon SK S7N 5E2, Canada, [email protected] ABSTRACT 1979; Bambach, 1977; Sepkoski, 1978, 1979, and Droser, 2004; Mángano and Buatois, Tracking biodiversity changes based on 1984, 1997). However, this has been marked 2014; Buatois et al., 2016a), rather than on body fossils through geologic time became by controversies regarding the nature of the whole Phanerozoic. In this study we diversity trajectories and their potential one of the main objectives of paleontology tackle this issue based on a systematic and biases (e.g., Sepkoski et al., 1981; Alroy, in the 1980s. Trace fossils represent an alter- global compilation of trace-fossil data 2010; Crampton et al., 2003; Holland, 2010; native record to evaluate secular changes in in the stratigraphic record. We show that Bush and Bambach, 2015). In these studies, diversity. A quantitative ichnologic analysis, quantitative ichnologic analysis indicates diversity has been invariably assessed based based on a comprehensive and global data that the three main marine evolutionary on body fossils. set, has been undertaken in order to evaluate radiations inferred from body fossils, namely Trace fossils represent an alternative temporal trends in diversity of bioturbation the Cambrian Explosion, Great Ordovician record to assess secular changes in bio- and bioerosion structures. The results of this Biodiversification Event, and Mesozoic diversity. Trace-fossil data were given less study indicate that the three main marine Marine Revolution, are also expressed in the attention and were considered briefly in evolutionary radiations (Cambrian Explo- trace-fossil record. -

Ecological Sorting of Vascular Plant Classes During the Paleozoic Evolutionary Radiation

i1 Ecological Sorting of Vascular Plant Classes During the Paleozoic Evolutionary Radiation William A. DiMichele, William E. Stein, and Richard M. Bateman DiMichele, W.A., Stein, W.E., and Bateman, R.M. 2001. Ecological sorting of vascular plant classes during the Paleozoic evolutionary radiation. In: W.D. Allmon and D.J. Bottjer, eds. Evolutionary Paleoecology: The Ecological Context of Macroevolutionary Change. Columbia University Press, New York. pp. 285-335 THE DISTINCTIVE BODY PLANS of vascular plants (lycopsids, ferns, sphenopsids, seed plants), corresponding roughly to traditional Linnean classes, originated in a radiation that began in the late Middle Devonian and ended in the Early Carboniferous. This relatively brief radiation followed a long period in the Silurian and Early Devonian during wrhich morphological complexity accrued slowly and preceded evolutionary diversifications con- fined within major body-plan themes during the Carboniferous. During the Middle Devonian-Early Carboniferous morphological radiation, the major class-level clades also became differentiated ecologically: Lycopsids were cen- tered in wetlands, seed plants in terra firma environments, sphenopsids in aggradational habitats, and ferns in disturbed environments. The strong con- gruence of phylogenetic pattern, morphological differentiation, and clade- level ecological distributions characterizes plant ecological and evolutionary dynamics throughout much of the late Paleozoic. In this study, we explore the phylogenetic relationships and realized ecomorphospace of reconstructed whole plants (or composite whole plants), representing each of the major body-plan clades, and examine the degree of overlap of these patterns with each other and with patterns of environmental distribution. We conclude that 285 286 EVOLUTIONARY PALEOECOLOGY ecological incumbency was a major factor circumscribing and channeling the course of early diversification events: events that profoundly affected the structure and composition of modern plant communities. -

Marissa Pitter, “Unearthing the Unknown: the Fossils of The

1 Unearthing the Unknown: The Fossils of the Budden Collection Marissa Pitter Fig. 1. South Gallery Room. Hinckley, Maine: L.C. Bates Museum. Photo: John Meader Photography, ©2020. In the South Gallery Room of the L.C. Bates Museum sit eight fossil display cases. In the cramped sixth case rests a significant fossil, the Pertica quadrifaria—Maine’s state fossil which comes from the rocks of the world-renowned Trout Valley Formation. Alongside the rare fossilized remains of Pertica lies “The Budden Collection,” a group of seven fossils found in northern Maine and donated to the museum in 2013. A label sits below each fossil identifying the name of the specimen (and at times, its genus and species), the geologic period and 2 formation, and the location where the fossil was found. The exact descriptions that the L.C. Bates Museum provides on the labels is given in Table 1. Table 1. The Budden Collection Fossils Fossil Geologic Period Geologic Formation Location Favositid Coral (1) Silurian Hardwood Mountain Hobbstown Township, Maine Favositid Coral (2) Silurian Hardwood Mountain Hobbstown Township, Maine Horn coral with trace Devonian Seboomook Tomhegan Township, fossils Maine Rugose Coral Ordovician/Silurian Formation Unknown Shin Pond, Maine Brachiopod Devonian Seboomook Tomhegan Township, Mucrospirifer? Maine Brachiopods likely Devonian Formation Unknown Big Moose Township, steinkerns (fossilized Maine outlines) Leptostrophia and Devonian likely Seboomook Big Moose Township, Tentaculites Maine The question mark following “Mucrospirifer,” the unknown geologic formations, and the impreciseness of the geologic age of the rugose coral indicate there are some uncertainties among the museum’s identifications. The table also points to some commonalities among the fossil collection. -

Proceedings of the United States National Museum

NEW SPECIES OF SILURIAN FOSSILS FROM THE ED:N'IUNDS AND PEMBROKE FORMATIONS OF WASHINGTON COUNTY, MAINE. By Henry Shaler Williams, Of Cornell University, Ithaca, New Yorh. INTRODUCTION. In preparing the Eastport folio of the United States Geological Survey for pubhcation the more characteristic fossils of the Silurian formations there mapped were selected for illustration. Among them the following were new, and as the folio is an inconvenient place for publishing descriptions of new species, the following paper will describe and illustrate a few of the more common and characteristic new species found in the Edmunds and Pembroke formations of Washington County, Maine. The type-specimens of all of these new species are in the collections of the United States National Museum, and the catalogue numbers under which they are registered are indi- cated in the following descriptions. For greater precision the Geo- logical Survey locality numbers and my own numbers given to indi- vidual specimens are also noted wherever necessary. The species from the Edmunds formation are: Whitfieldella edmundsi. Palaeopecten cobscooH. Chonetes edmundsi. Palaeopecten transversalis. Chonetes cobscooki. Tolmaia compestris. Brachyprion shaleri. Pterinea (f Tolmaia) trescotti. The Pembroke species are: Chonetes bastini. Grammysia pembrohensis. Camarotoechia leightoni. Lingula minima var. americana. Actinopteria bella. Modiolopsis leightoni. Actinopteriafornicata. Modiolopsis leightoni var. quodraJta. Actinopteria dispar. Nuculites corrugata. Lingula scobina. Leiopteria rubra. On plate 30, illustrating the Pembroke fauna, are also included figures of Dalmanella lunata (Sowerby), and on plate 31, Eurymyella shaleri var. minor, WiUiams, the type of which was described from the Eastport formation,^ (formation No. V), and figures of Platij- 1 Proc. -

The Classification of Early Land Plants-Revisited*

The classification of early land plants-revisited* Harlan P. Banks Banks HP 1992. The c1assificalion of early land plams-revisiled. Palaeohotanist 41 36·50 Three suprageneric calegories applied 10 early land plams-Rhyniophylina, Zoslerophyllophytina, Trimerophytina-proposed by Banks in 1968 are reviewed and found 10 have slill some usefulness. Addilions 10 each are noted, some delelions are made, and some early planls lhal display fealures of more lhan one calegory are Sel aside as Aberram Genera. Key-words-Early land-plams, Rhyniophytina, Zoslerophyllophytina, Trimerophytina, Evolulion. of Plant Biology, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York-5908, U.S.A. 14853. Harlan P Banks, Section ~ ~ ~ <ltm ~ ~-~unR ~ qro ~ ~ ~ f~ 4~1~"llc"'111 ~-'J~f.f3il,!"~, 'i\'1f~()~~<1I'f'I~tl'1l ~ ~1~il~lqo;l~tl'1l, 1968 if ~ -mr lfim;j; <fr'f ~<nftm~~Fmr~%1 ~~ifmm~~-.mtl ~if-.t~m~fuit ciit'!'f.<nftmciit~%1 ~ ~ ~ -.m t ,P1T ~ ~~ lfiu ~ ~ -.t 3!ftrq; ~ ;j; <mol ~ <Rir t ;j; w -.m tl FIRST, may I express my gratitude to the Sahni, to survey briefly the fate of that Palaeobotanical Sociery for the honour it has done reclassification. Several caveats are necessary. I recall me in awarding its International Medal for 1988-89. discussing an intractable problem with the late great May I offer the Sociery sincere thanks for their James M. Schopf. His advice could help many consideration. aspiring young workers-"Survey what you have and Secondly, may I join in celebrating the work and write up that which you understand. The rest will the influence of Professor Birbal Sahni. The one time gradually fall into line." That is precisely what I did I met him was at a meeting where he was displaying in 1968. -

An Inventory of Trilobites from National Park Service Areas

Sullivan, R.M. and Lucas, S.G., eds., 2016, Fossil Record 5. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 74. 179 AN INVENTORY OF TRILOBITES FROM NATIONAL PARK SERVICE AREAS MEGAN R. NORR¹, VINCENT L. SANTUCCI1 and JUSTIN S. TWEET2 1National Park Service. 1201 Eye Street NW, Washington, D.C. 20005; -email: [email protected]; 2Tweet Paleo-Consulting. 9149 79th St. S. Cottage Grove. MN 55016; Abstract—Trilobites represent an extinct group of Paleozoic marine invertebrate fossils that have great scientific interest and public appeal. Trilobites exhibit wide taxonomic diversity and are contained within nine orders of the Class Trilobita. A wealth of scientific literature exists regarding trilobites, their morphology, biostratigraphy, indicators of paleoenvironments, behavior, and other research themes. An inventory of National Park Service areas reveals that fossilized remains of trilobites are documented from within at least 33 NPS units, including Death Valley National Park, Grand Canyon National Park, Yellowstone National Park, and Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve. More than 120 trilobite hototype specimens are known from National Park Service areas. INTRODUCTION Of the 262 National Park Service areas identified with paleontological resources, 33 of those units have documented trilobite fossils (Fig. 1). More than 120 holotype specimens of trilobites have been found within National Park Service (NPS) units. Once thriving during the Paleozoic Era (between ~520 and 250 million years ago) and becoming extinct at the end of the Permian Period, trilobites were prone to fossilization due to their hard exoskeletons and the sedimentary marine environments they inhabited. While parks such as Death Valley National Park and Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve have reported a great abundance of fossilized trilobites, many other national parks also contain a diverse trilobite fauna. -

Devonian As a Time of Major Innovation in Plants and Their Communities

1 Back to the Beginnings: The Silurian- 2 Devonian as a Time of Major Innovation 15 3 in Plants and Their Communities 4 Patricia G. Gensel, Ian Glasspool, Robert A. Gastaldo, 5 Milan Libertin, and Jiří Kvaček 6 Abstract Silurian, with the Early Silurian Cooksonia barrandei 31 7 Massive changes in terrestrial paleoecology occurred dur- from central Europe representing the earliest vascular 32 8 ing the Devonian. This period saw the evolution of both plant known, to date. This plant had minute bifurcating 33 9 seed plants (e.g., Elkinsia and Moresnetia), fully lami- aerial axes terminating in expanded sporangia. Dispersed 34 10 nate∗ leaves and wood. Wood evolved independently in microfossils (spores and phytodebris) in continental and 35AU2 11 different plant groups during the Middle Devonian (arbo- coastal marine sediments provide the earliest evidence for 36 12 rescent lycopsids, cladoxylopsids, and progymnosperms) land plants, which are first reported from the Early 37 13 resulting in the evolution of the tree habit at this time Ordovician. 38 14 (Givetian, Gilboa forest, USA) and of various growth and 15 architectural configurations. By the end of the Devonian, 16 30-m-tall trees were distributed worldwide. Prior to the 17 appearance of a tree canopy habit, other early plant groups 15.1 Introduction 39 18 (trimerophytes) that colonized the planet’s landscapes 19 were of smaller stature attaining heights of a few meters Patricia G. Gensel and Milan Libertin 40 20 with a dense, three-dimensional array of thin lateral 21 branches functioning as “leaves”. Laminate leaves, as we We are now approaching the end of our journey to vegetated 41 AU3 22 now know them today, appeared, independently, at differ- landscapes that certainly are unfamiliar even to paleontolo- 42 23 ent times in the Devonian. -

Towards a Phylogenetic Nomenclature of Tracheophyta

Cantino & al. • Phylogenetic nomenclature of Tracheophyta TAXON 56 (3) • August 2007: 822–846 PHYLOGENEtic noMEncLAturE Towards a phylogenetic nomenclature of Tracheophyta Philip D. Cantino2, James A. Doyle1,3, Sean W. Graham1,4, Walter S. Judd1,5, Richard G. Olmstead1,6, Douglas E. Soltis1,5, Pamela S. Soltis1,7 & Michael J. Donoghue8 1 Authors are listed alphabetically, except for the first and last authors. 2 Department of Environmental and Plant Biology, Ohio University, Athens, Ohio 45701, U.S.A. [email protected] (author for correspondence) 3 Section of Evolution and Ecology, University of California, Davis, California 95616, U.S.A. 4 UBC Botanical Garden and Centre for Plant Research, 6804 SW Marine Drive, The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada V6T 1Z4 5 Department of Botany, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32611-8526, U.S.A. 6 Department of Biology, P.O. Box 355325, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington 98195-5325, U.S.A. 7 Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32611, U.S.A. 8 Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology and Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University, P.O. Box 208106, New Haven, Connecticut 06520-8106, U.S.A. This is an abbreviated version of a paper that appears in full in the Electronic supplement to Taxon. Phylogenetic definitions are provided for the names of 20 clades of vascular plants (plus 33 others in the electronic supple- ment). Emphasis has been placed on well-supported clades that are widely known to non-specialists and/or have a deep origin within Tracheophyta or Angiospermae. -

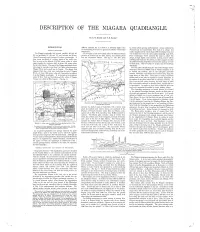

Description of the Niagara Quadrangle

DESCRIPTION OF THE NIAGARA QUADRANGLE. By E. M. Kindle and F. B. Taylor.a INTRODUCTION. different altitudes, but as a whole it is distinctly higher than by broad valleys opening northwestward. Across northwestern GENERAL RELATIONS. the surrounding areas and is in general bounded by well-marked Pennsylvania and southwestern New York it is abrupt and escarpments. i nearly straight and its crest is about 1000 feet higher than, and The Niagara quadrangle lies between parallels 43° and 43° In the region of the lower Great Lakes the Glaciated Plains 4 or 5 miles back from the narrow plain bordering Lake Erie. 30' and meridians 78° 30' and 79° and includes the Wilson, province is divided into the Erie, Huron, and Ontario plains From Cattaraugus Creek eastward the scarp is rather less Olcott, Tonawanda, and Lockport 15-minute quadrangles. It and the Laurentian Plateau. (See fig. 2.) The Erie plain abrupt, though higher, and is broken by deep, narrow valleys thus covers one-fourth of a square degree of the earth's sur extending well back into the plateau, so that it appears as a line face, an area, in that latitude, of 870.9 square miles, of which of northward-facing steep-sided promontories jutting out into approximately the northern third, or about 293 square miles, the Erie plain. East of Auburn it merges into the Onondaga lies in Lake Ontario. The map of the Niagara quadrangle shows escarpment. also along its west side a strip from 3 to 6 miles wide comprising The Erie plain extends along the base of the Portage escarp Niagara River and a small area in Canada.