Imagine a Lifeless Body Hanging from a Noose. This Body Is a Marker Not Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A FRIGHTFUL VENGEANCE: LYNCHING and CAPITAL PUNISHMENT in TURN-OF-THE-CENTURY COLORADO By

A FRIGHTFUL VENGEANCE: LYNCHING AND CAPITAL PUNISHMENT IN TURN-OF-THE-CENTURY COLORADO by JEFFREY A. WERMER B.A., Reed College, 2006 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History 2014 This thesis entitled: A Frightful Vengeance: Lynching and Capital Punishment in Turn-of-the-Century Colorado written by Jeffrey A. Wermer has been approved for the Department of History Dr. Thomas Andrews, Committee Chair Dr. Fred Anderson, Committee Member Dr. Paul Sutter, Committee Member Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. iii Wermer, Jeffrey A. (M.A., History) A Frightful Vengeance: Lynching and Capital Punishment in Turn-of-the-Century Colorado Thesis directed by Associate Professor Thomas Andrews Having abolished the death penalty four years prior, Coloradoans lynched three men—Thomas Reynolds, Calvin Kimblern, and John Preston Porter, Jr.— in 1900, hanging two and burning one at the stake. This thesis argues that these lynchings both represented and supported Colorado’s culture of lynching, a combination of social and cultural connections in which lynching was used as a force for social cohesion and control. Rather than being a distinct frontier culture of lynching, Colorado’s culture was a slightly attenuated version of the racially-motivated culture of lynching in the Jim Crow South. The three lynchings in 1900 lay at the heart of the political debate over the reinstatement of capital punishment in 1901. -

©2013 Luis-Alejandro Dinnella-Borrego ALL RIGHTS

©2013 Luis-Alejandro Dinnella-Borrego ALL RIGHTS RESERVED “THAT OUR GOVERNMENT MAY STAND”: AFRICAN AMERICAN POLITICS IN THE POSTBELLUM SOUTH, 1865-1901 By LUIS-ALEJANDRO DINNELLA-BORREGO A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History written under the direction of Mia Bay and Ann Fabian and approved by ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “That Our Government May Stand”: African American Politics in the Postbellum South, 1865-1913 by LUIS-ALEJANDRO DINNELLA-BORREGO Dissertation Director: Mia Bay and Ann Fabian This dissertation provides a fresh examination of black politics in the post-Civil War South by focusing on the careers of six black congressmen after the Civil War: John Mercer Langston of Virginia, James Thomas Rapier of Alabama, Robert Smalls of South Carolina, John Roy Lynch of Mississippi, Josiah Thomas Walls of Florida, and George Henry White of North Carolina. It examines the career trajectories, rhetoric, and policy agendas of these congressmen in order to determine how effectively they represented the wants and needs of the black electorate. The dissertation argues that black congressmen effectively represented and articulated the interests of their constituents. They did so by embracing a policy agenda favoring strong civil rights protections and encompassing a broad vision of economic modernization and expanded access for education. Furthermore, black congressmen embraced their role as national leaders and as spokesmen not only for their congressional districts and states, but for all African Americans throughout the South. -

Heritage and Hate in Lexington, North Carolina

THEMAN ON THEMONUMENT: HERITAGEAND HATE INLEXINGTON, NORTH CAROLINA oy HayleyM McCulloch Honors Tnesis Appalachian StateUniversity Submittedto theDepartment of History andThe HonorsCollege in partialfulfillment of the requirementsthe fur degreeof Bachelorof Science May,2019 Approved by: J!iZ{iJ!t.-----X.arl Campbell, Ph.D, Thesis Director ���..;;; fff!,�f/Ld � MichaelBehrent, Ph:D, DepartmentalHonors Director Jefford Vahlbusch,Ph.D., Dean, TheHonors College Revised716/2017 McCulloch 1 Abstract Confederate monuments were brought into the national spotlight after the Unite the Right Rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, and the murder of African Americans worshipping in a church in Charleston, South Carolina. The debate over how to define Confederate monuments and what to do with them in the twenty-first century is often boiled down to this: are Confederate monuments vestiges of heritage or hatred? To symbolize heritage would mean that Confederate monuments are merely memorials to the sacrifices and patriotism of southern men who fought for their country. Conversely, to embody hatred signifies that Confederate monuments represent white supremacy and the oppression of African Americans after emancipation. This thesis will address the popular debate between heritage and hate through an historical case study of a Confederate monument in a small North Carolina town called Lexington, which is the governing seat of Davidson County. The monument’s historical context will be analyzed through a breakdown of Lost Cause ideology and its implications for the history of Davidson County. The Lexington monument is a product of a deeply complicated local history involving people who truly believed they were commemorating men, their fathers and grandfathers, who defended their community. -

INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced

INFO RM A TIO N TO U SER S This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI film s the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be fromany type of con^uter printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependentquality upon o fthe the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and inqjroper alignment can adverse^ afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note wiD indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one e3q)osure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photogr^hs included inoriginal the manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for aiy photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI direct^ to order. UMJ A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313.'761-4700 800/521-0600 LAWLESSNESS AND THE NEW DEAL; CONGRESS AND ANTILYNCHING LEGISLATION, 1934-1938 DISSERTATION presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Robin Bernice Balthrope, A.B., J.D., M.A. -

A Study of Early Utah-Montana Trade, Transportation, and Communication, 1847-1881

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1959 A Study of Early Utah-Montana Trade, Transportation, and Communication, 1847-1881 L. Kay Edrington Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Mormon Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Edrington, L. Kay, "A Study of Early Utah-Montana Trade, Transportation, and Communication, 1847-1881" (1959). Theses and Dissertations. 4662. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4662 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. A STUDY OF EARLY UTAH-MONTANA TRADE TRANSPORTATION, AND COMMUNICATION 1847-1881 A Thesis presented to the department of History Brigham young university provo, Utah in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree Master of science by L. Kay Edrington June, 1959 This thesis, by L. Kay Edrington, is accepted In its present form by the Department of History of Brigham young University as Satisfying the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Science. May 9, 1959 lywrnttt^w-^jmrnmr^^^^ The writer wishes to express appreciation to a few of those who made this thesis possible. Special acknowledge ments are due: Dr. leRoy R. Hafen, Chairman, Graduate Committee. Dr. Keith Melville, Committee member. Staffs of; History Department, Brigham young university. Brigham young university library. L.D.S. Church Historian's office. Utah Historical Society, Salt lake City. -

Andreas Fischer: Ghost Town Andreas Fischer: Ghost Town the 1860S

Ghost Town Andreas Fischer Gahlberg Gallery College of DuPage 425 Fawell Blvd. Glen Ellyn, IL 60137- 6599 www.cod.edu/gallery (630) 942-2321 College of DuPage Ghost Town Andreas Fischer Gahlberg Gallery Hyde Park Arts Center, Chicago Jan. 21 to Feb. 27, 2010 Jan. 17 to April 18, 2010 Ghost Town address this absence. Through material of skin is conveyed through mottled strokes facts of paint these bodies of images of pink, gray and green, giving some of the As any good horror story demonstrates, attempt to extend beyond basic linguistic figures a distinctly zombielike appearance. there are consequences to reanimating the representation into broader experience. So too do their eyes, which Fischer often dead. Or at least, there should be. Ghosts, conveys with a few strokes of brown or zombies, vampires and other creatures “Both bodies of work are meant to mimic black so that the sockets appear as gaping from the realm of the beyond have earned kinds of historical fragments. They pretend hollows. A single curved brushstroke may their uncanny badges in part because they to document. More importantly, though, evoke a pair of pursed lips, a slackened take the form of someone who was once they attempt to use paint activity to tap jaw or other facial grimace that hints recognizably human, coursing with blood into imaginative characteristics that make at a quality that is somehow essential to and feeling. Yet not for a moment can such up subjective experience.” the character, and yet other areas of the creatures be mistaken for the people they composition will be more crudely evoked once were. -

Backcountry Robbers, River Pirates, and Brawling Boatmen: Transnational Banditry in Antebellum U.S

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2018 Backcountry Robbers, River Pirates, and Brawling Boatmen: Transnational Banditry in Antebellum U.S. Frontier Literature Samuel M. Lackey University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Lackey, S. M.(2018). Backcountry Robbers, River Pirates, and Brawling Boatmen: Transnational Banditry in Antebellum U.S. Frontier Literature. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/4656 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Backcountry Robbers, River Pirates, and Brawling Boatmen: Transnational Banditry in Antebellum U.S. Frontier Literature by Samuel M. Lackey Bachelor of Arts University of South Carolina, 2006 Bachelor of Arts University of South Carolina, 2006 Master of Arts College of Charleston, 2009 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2018 Accepted by: Gretchen Woertendyke, Major Professor David Greven, Committee Member David Shields, Committee Member Keri Holt, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Samuel M. Lackey, 2018 All Rights Reserved. ii Acknowledgements First, I would like to thank my parents for all of their belief and support. They have always pushed me forward when I have been stuck in place. To my dissertation committee – Dr. -

Colors of the Western Mining Frontier Painted Finishes in Virginia City

COLORS OF THE WESTERN MINING FRONTIER PAINTED FINISHES IN VIRGINIA CITY, MONTANA by KATHRYN GERAGHTY A THESIS Presented to the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Historic Preservation and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science June 2017 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Kathryn Geraghty Title: Colors of the Western Mining Frontier: Painted Finishes in Virginia City, Montana This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science degree in the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Historic Preservation by: Kingston Heath Chair Shannon Sardell Member Carin Carlson Member and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2017. ii © 2017 Kathryn Geraghty iii THESIS ABSTRACT Kathryn Geraghty Master of Science Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Historic Preservation June 2017 Title: Colors of the Western Mining Frontier: Painted Finishes in Virginia City, Montana Virginia City once exemplified the cutting edge of culture and taste in the Rocky Mountain mining frontier. Weathering economic downturns, mining booms and busts, and the loss of the territorial capital to Helena, Virginia City survives today as a heritage tourism site with a substantial building stock from its period of significance, 1863-1875. However, the poor physical condition and interpretation of the town offers tourists an inauthentic experience. Without paint analysis, the Montana Heritage Commission, state- appointed caretakers of Virginia City cannot engage in rehabilitation. As of 2017, no published architectural finishes research exists that provides comparative case studies for the Anglo-American settlement of the American West between 1840-1880, for American industrial landscapes, or for vernacular architecture in Montana. -

The Vigilantes of Montana

The Vigilantes of Montana Thomas Josiah Dimsdale The Vigilantes of Montana Table of Contents The Vigilantes of Montana.......................................................................................................................................1 Thomas Josiah Dimsdale...............................................................................................................................2 CHAPTER I. Introductory—Vigilance Committees.....................................................................................4 CHAPTER II. The Sunny Side of Mountain Life..........................................................................................9 CHAPTER III. Settlement of Montana........................................................................................................10 CHAPTER IV. The Road Agents................................................................................................................11 CHAPTER V. The Dark Days of Montana..................................................................................................13 CHAPTER VI. The Trial.............................................................................................................................17 CHAPTER VII. Plummer Versus Crawford................................................................................................18 CHAPTER VIII. A Calendar of Crimes......................................................................................................21 CHAPTER IX. Perils of the Road...............................................................................................................24 -

VCT 8 Squab of a Girl Who Fancies Herself Stan, the Sheep Boy the Loveliest Creature in Existence Author: Gladys M

ADULT FICTION (AF) ............................1 VCT 29 Children Of God SPANISH LANGUAGE BOOKS ..........32 Author: Vardis Fisher ADULT NON-FICTION (AN).................33 Read by: Carol Adair Critical history of the Mormon faith. JUVENILE FICTION (JF) ...................100 5 Cassettes JUVENILE NON-FICTION (JN)..........110 BOOKS BY TITLE..............................113 VCT 35 April BOOKS BY AUTHOR ........................152 Author: Vardis Fisher Adult Fiction (AF) Read by: Laurel Wagers The tale of June Weeg, a homely VCT 8 squab of a girl who fancies herself Stan, The Sheep Boy the loveliest creature in existence Author: Gladys M. Campbell until at last she recognizes and Read by: Kay Salmon achieves a deeper poetry of living. The story of a young boy growing A story of love up on a ranch. 1 Cassette 3 Cassettes VCT 12 Jenny Of The Tetons Author: Kristiana Gregory PLEASE Read by: Irene Warren Orphaned by an Indian raid, 15 year old Carrie is befriended. REWIND 1 Cassette TAPES VCT 25 LTAI Housekeeping Author: Marilynn Robinson Read by: Carla Stern A haunting lyrical novel of great VCT 49 beauty, steeped in images of earth, Caleb's Miracle and Two Other water, air and fire. Housekeeping Stories is the story of Ruth and her Author: M. R. Compton Jr memories as she grows from Read by: M. Compton childhood to adulthood on a Rich human experience of four brooding glacial lake in the towering generations in Montana and mountains of Idaho. Northern Idaho, saga of a family. 1 Cassette A Christmas Story.. 1 Cassette - 1 - VCT 51 VCT 78 Harvester (The) Divine Passion (The) Author: Lorraine Kettlewell Author: Vardis Fisher Read by: Mira Batt Read by: Mira Batt Story of a tyrannical wheat rancher. -

163-64 Hutchens, John K., One Man's Montana

Hustvedt, Lloyd, Rasmus Bjørn Anderson, Hyatt, Glenn, 80(4):128-32, 90(2):108 11-15, 17, 39(3):200-10 Pioneer Scholar, review, 58(3):163-64 Hydaburg Indian Reservation, 82(4):142, 145, Hyland, Thomas A., 39(3):204 Hutchens, John K., One Man’s Montana: An 147 Hyman, Harold M., Soldiers and Spruce: Informal Portrait of a State, review, Hydaburg Trading Company, 106(4):172 Origins of the Loyal Legion of Loggers 56(3):136-37 Hyde, Amasa L., 33(3):337 and Lumbermen, review, 55(3):135- Hutcheson, Austin E., rev. of Gold Rush: The Hyde, Anne F., An American Vision: Far 36; To Try Men’s Souls: Loyalty Tests in Journals, Drawings, and Other Papers Western Landscape and National American History, review, 52(2):76-77; of J. Goldsborough Bruff—Captain, Culture, 1820-1920, review, 83(2):77; rev. of False Witness, 61(3):181-82 Washington City and California Mining rev. of Americans Interpret the Hyman, Sidney, The Lives of William Benton, Association, April 2, 1849–July 20, 1851, Parthenon: The Progression of Greek review, 64(1):41-42; Marriner S. 40(4):345-46; rev. of The Mountain Revival Architecture from the East Coast Eccles: Private Entrepreneur and Public Meadows Massacre, 42(3):248-49 to Oregon, 1800-1860, 84(3):109; rev. of Servant, review, 70(2):84 Hutcheson, Elwood, 49(3):110 Bonanza Rich: Lifestyles of the Western Hymes, Dell, rev. of Pioneers of American Hutchins, Charles, 37(1):48-49, 54 Mining Entrepreneurs, 83(3):116 Anthropology: The Uses of Biography, Hutchins, James S., ed., Wheel Boats on the Hyde, Charles Leavitt, The Story of an -

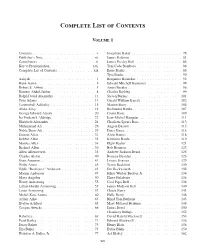

Complete List of Contents

Complete List of Contents Volume 1 Contents. v Josephine Baker . 78 Publisher’s Note . vii James Baldwin. 81 Contributors . xi James Presley Ball. 84 Key to Pronunciation. xvii Toni Cade Bambara . 86 Complete List of Contents . xix Ernie Banks . 88 Tyra Banks. 90 Aaliyah . 1 Benjamin Banneker . 92 Hank Aaron . 3 Edward Mitchell Bannister . 94 Robert S. Abbott . 5 Amiri Baraka . 96 Kareem Abdul-Jabbar . 8 Charles Barkley . 99 Ralph David Abernathy . 11 Steven Barnes . 101 Faye Adams . 14 Gerald William Barrax . 102 Cannonball Adderley . 15 Marion Barry . 104 Alvin Ailey . 18 Richmond Barthé. 107 George Edward Alcorn . 20 Count Basie . 109 Ira Frederick Aldridge. 22 Jean-Michel Basquiat . 111 Elizabeth Alexander . 24 Charlotta Spears Bass . 113 Muhammad Ali . 26 Angela Bassett . 115 Noble Drew Ali . 29 Daisy Bates. 116 Damon Allen . 31 Alvin Batiste . 118 Debbie Allen . 33 Kathleen Battle. 119 Marcus Allen . 34 Elgin Baylor . 121 Richard Allen . 36 Bob Beamon . 123 Allen Allensworth . 38 Andrew Jackson Beard. 125 Charles Alston . 40 Romare Bearden . 126 Gene Ammons. 41 Louise Beavers . 129 Wally Amos . 43 Tyson Beckford . 130 Eddie “Rochester” Anderson . 45 Jim Beckwourth . 132 Marian Anderson . 47 Julius Wesley Becton, Jr. 134 Maya Angelou . 50 Harry Belafonte . 136 Henry Armstrong . 53 Cool Papa Bell . 138 Lillian Hardin Armstrong . 55 James Madison Bell . 140 Louis Armstrong . 57 Chuck Berry . 141 Molefi Kete Asante . 60 Halle Berry . 144 Arthur Ashe . 63 Blind Tom Bethune . 145 Evelyn Ashford . 65 Mary McLeod Bethune . 148 Crispus Attucks . 66 James Bevel . 150 Chauncey Billups . 152 Babyface. 69 David Harold Blackwell . 153 Pearl Bailey . 71 Edward Blackwell .