A Brief Life of Swami Vivekananda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Swami Vivekananda

Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda Volume 9 Letters (Fifth Series) Lectures and Discourses Notes of Lectures and Classes Writings: Prose and Poems (Original and Translated) Conversations and Interviews Excerpts from Sister Nivedita's Book Sayings and Utterances Newspaper Reports Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda Volume 9 Letters - Fifth Series I Sir II Sir III Sir IV Balaram Babu V Tulsiram VI Sharat VII Mother VIII Mother IX Mother X Mother XI Mother XII Mother XIII Mother XIV Mother XV Mother XVI Mother XVII Mother XVIII Mother XIX Mother XX Mother XXI Mother XXII Mother XXIII Mother XXIV Mother XXV Mother XXVI Mother XXVII Mother XXVIII Mother XXIX Mother XXX Mother XXXI Mother XXXII Mother XXXIII Mother XXXIV Mother XXXV Mother XXXVI Mother XXXVII Mother XXXVIII Mother XXXIX Mother XL Mrs. Bull XLI Miss Thursby XLII Mother XLIII Mother XLIV Mother XLV Mother XLVI Mother XLVII Miss Thursby XLVIII Adhyapakji XLIX Mother L Mother LI Mother LII Mother LIII Mother LIV Mother LV Friend LVI Mother LVII Mother LVIII Sir LIX Mother LX Doctor LXI Mother— LXII Mother— LXIII Mother LXIV Mother— LXV Mother LXVI Mother— LXVII Friend LXVIII Mrs. G. W. Hale LXIX Christina LXX Mother— LXXI Sister Christine LXXII Isabelle McKindley LXXIII Christina LXXIV Christina LXXV Christina LXXVI Your Highness LXXVII Sir— LXXVIII Christina— LXXIX Mrs. Ole Bull LXXX Sir LXXXI Mrs. Bull LXXXII Mrs. Funkey LXXXIII Mrs. Bull LXXXIV Christina LXXXV Mrs. Bull— LXXXVI Miss Thursby LXXXVII Friend LXXXVIII Christina LXXXIX Mrs. Funkey XC Christina XCI Christina XCII Mrs. Bull— XCIII Sir XCIV Mrs. Bull— XCV Mother— XCVI Sir XCVII Mrs. -

The Role of the Ramakrishna Mission and Human

TOWARDS SERVING THE MANKIND: THE ROLE OF THE RAMAKRISHNA MISSION AND HUMAN DEVELOPMENT IN INDIA Karabi Mitra Bijoy Krishna Girls’ College Howrah, West Bengal, India sanjay_karabi @yahoo.com / [email protected] Abstract In Indian tradition religious development of a person is complete when he experiences the world within himself. The realization of the existence of the omnipresent Brahman --- the Great Spirit is the goal of the spiritual venture. Gradually traditional Hinduism developed negative elements born out of age-old superstitious practices. During the nineteenth century changes occurred in the socio-cultural sphere of colonial India. Challenges from Christianity and Brahmoism led the orthodox Hindus becoming defensive of their practices. Towards the end of the century the nationalist forces identified with traditional Hinduism. Sri Ramakrishna, a Bengali temple-priest propagated a new interpretation of the Hindu scriptures. Without formal education he could interpret the essence of the scriptures with an unprecedented simplicity. With a deep insight into the rapidly changing social scenario he realized the necessity of a humanist religious practice. He preached the message to serve the people as the representative of God. In an age of religious debates he practiced all the religions and attained at the same Truth. Swami Vivekananda, his closest disciple carried the message to the Western world. In the Conference of World religions held at Chicago (1893) he won the heart of the audience by a simple speech which reflected his deep belief in the humanist message of the Upanishads. Later on he was successful to establish the Ramakrishna Mission at Belur, West Bengal. -

Kriya Yoga of Mahavatar Babaji

Kriya Yoga of Mahavatar Babaji Kriya Yoga Kriya Yoga, the highest form of pranayam (life force control), is a set of techniques by which complete realization may be achieved. In order to prepare for the practice of Kriya Yoga, the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali are to be studied, the Eight Fold Path learned and adheared to; the Bhagavad Gita is to be read, studied and meditated upon; and a Disciple-Guru relationship entered into freely with the Guru who will initiate the disciple into the actual Kriya Yoga techniques. These techniques themselves, given by the Guru, are to be done as per the Mahavatar Babaji gurus instructions for the individual. There re-introduced this ancient technique in are also sources for Kriya that are guru-less. 1861 and gave permission for it's See the Other Resources/Non Lineage at the dissemination to his disciple Lahiri bottom of organizations Mahasay For more information on Kriya Yoga please use these links and the ones among the list of Kriya Yoga Masters. Online Books A Personal Experience More Lineage Organizations Non Lineage Resources Message Boards/Groups India The information shown below is a list of "Kriya Yoga Gurus". Simply stated, those that have been given permission by their Guru to initiate others into Kriya Yoga. Kriya Yoga instruction is to be given directly from the Guru to the Disciple. When the disciple attains realization the Guru may give that disciple permission to initiate and instruct others in Kriya Yoga thus continuing the line of Kriya Yoga Gurus. Kriya Yoga Gurus generally provide interpretations of the Yoga Sutras and Gitas as part of the instructions for their students. -

Expand Your Heart – Vkjuly19

1 TheVedanta Kesari July 2019 1 The Vedanta Kesari The Vedanta Cover Story page 11... 1 A Cultural and Spiritual Monthly `15 July of the Ramakrishna Order since 1914 2019 TheTheVedanta Kesari Sri Ramakrishna Math, Mylapore, Chennai 600 004 h(044) 2462 1110 E-mail: [email protected] Website : www.chennaimath.org DearDea Readers, TThe Vedanta Kesari is one of the oldest cultural aandnd sspiritual magazines in the country. Started under tthehe gguidance and support of Swami Vivekananda, the ffirstirs issue of the magazine, then called BBrahmavadinr , came out on 14 Sept 1895. July 2019 BrBrahmavadin was run by one of Swamiji’s ardent ffollowersol Sri Alasinga Perumal. After his death in 4 1190990 the magazine publication became irregular, aandnd stoppeds in 1914 whereupon the Ramakrishna OOrder revived it as The Vedanta Kesari. Swami Vivekananda’s concern for the mmagazine is seen in his letters to Alasinga Perumal whwheree he writes: ‘Now I am bent upon starting the journal.’ ‘Herewith I send a hundred dollars…. Hope this will go just a little in starting your The Vedanta Kesari The Vedanta paper.’ ‘I am determined to see the paper succeed.’ ‘The Song of the Sannyasin is my first contribution for your journal.’ ‘I learnt from your letter the bad financial state that Brahmavadin is in.’ ‘It must be supported by the Hindus if they have any sense of virtue or gratitude left in them.’ ‘I pledge myself to maintain the paper anyhow.’ ‘The Brahmavadin is a jewel—it must not perish. Of course, such a paper has to be kept up by private help always, and we will do it.’ For the last 105 years, without missing a single issue, the magazine has been carrying the invigorating message of Vedanta with articles on spirituality, culture, philosophy, youth, personality development, science, holistic living, family and corporate values. -

1893 Swami Brings Modern-Day Swamis to Annisquam

1893 Swami Brings Modern-Day Swamis to Annisquam For the celebration of the 150th anniversary of Vivekananda's birth, the Vedanta Societies of Boston and Providence joined with the Annisquam Village Church in an interfaith service on July 28, 2013. The service was filled with a wonderful energy. Saffron robes and languages ranging from French to Bengali make annual appearances at the Annisquam Village Church in Gloucester. Modern-day Hindu Pilgrims visit to pay homage and walk in the steps of Swami Vivekananda, the first Hindu monk in America, who spoke from the Church's pulpit in 1893, just before he made history at the first meeting of the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago (an adjunct event to the Columbian Exposition) as representative of Hinduism. Eloquent and, at the time, exotic, Vivekananda mesmerized his audiences both here and in Chicago, winning new respect for and interest in the religions of the East. He started the Vedanta Societies in America to spread his message of harmony of religions and inherent divinity of the soul. Vivekananda remained in Gloucester for several weeks during his two visits. First as the guest of John Henry Wright, a Greek professor at Harvard who helped Vivekananda make the arrangements for his Parliament appearance; and then he stayed at the Annisquam residence of Alpheus Hyatt, whose marine biology station on Lobster Cove was the first iteration of the present-day Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute. Hyatt was the father of Gloucester's renowned sculptor, Anna Hyatt (later Huntington), who would have been 17 at the time of the Swami's visit. -

Swami Vivekananda's Mission and Teachings

LIFE IS A VOYAGE1: Swami Vivekananda’s Mission and Teachings – A Cognitive Linguistic Analysis with Reference to the Theme of HOMECOMING Suren Naicker Abstract This study offers an in-depth analysis of the well-known LIFE AS A JOURNEY conceptual metaphor, applied to Vivekananda’s mission as he saw it, as well as his teachings. Using conceptual metaphor theory as a framework, Vivekananda’s Complete Works were manually and electronically mined for examples of how he conceptualized his own mission, which culminated in the formation of the Ramakrishna Math and Mission, a world-wide neo-Hindu organization. This was a corpus-based study, which starts with an overview of who Vivekananda was, including a discussion of his influence on other neo- Hindu leaders. This study shows that Vivekananda had a very clear understanding of his life’s mission, and saw himself almost in a messianic role, and was glad when his work was done, so he could return to his Cosmic ‘Home’. He uses these key metaphors to explain spiritual life in general as well as his own life’s work. Keywords: Vivekananda; neo-Hinduism; Ramakrishna; cognitive linguistics; conceptual metaphor theory 1 As is convention in the field of Cognitive Semantics, conceptual domains are written in UPPER CASE. Alternation Special Edition 28 (2019) 247 – 266 247 Print ISSN 1023-1757; Electronic ISSN: 2519-5476; DOI https://doi.org/10.29086/2519-5476/2019/sp28.4a10 Suren Naicker Introduction This article is an exposition of two conceptual metaphors based on the Complete Works2 of Swami Vivekananda. Conceptual metaphor theory is one of the key theories within the field of cognitive linguistics. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Thevedanta Kesari February 2020

1 TheVedanta Kesari February 2020 1 The Vedanta Kesari The Vedanta Cover Story Sri Ramakrishna : A Divine Incarnation page 11 A Cultural and Spiritual Monthly 1 `15 February of the Ramakrishna Order since 1914 2020 2 Mylapore Rangoli competition To preserve and promote cultural heritage, the Mylapore Festival conducts the Kolam contest every year on the streets adjoining Kapaleswarar Temple near Sri Ramakrishna Math, Chennai. Regd. Off. & Fact. : Plot No.88 & 89, Phase - II, Sipcot Industrial Complex, Ranipet - 632 403, Tamil Nadu. Editor: SWAMI MAHAMEDHANANDA Phone : 04172 - 244820, 651507, PRIVATE LIMITED Published by SWAMI VIMURTANANDA, Sri Ramakrishna Math, Chennai - 600 004 and Tele Fax : 04172 - 244820 (Manufacturers of Active Pharmaceutical Printed by B. Rajkumar, Chennai - 600 014 on behalf of Sri Ramakrishna Math Trust, Chennai - 600 004 and Ingredients and Intermediates) E-mail : [email protected] Web Site : www.svisslabss.net Printed at M/s. Rasi Graphics Pvt. Limited, No.40, Peters Road, Royapettah, Chennai - 600014. Website: www.chennaimath.org E-mail: [email protected] Ph: 6374213070 3 THE VEDANTA KESARI A Cultural and Spiritual Monthly of The Ramakrishna Order Vol. 107, No. 2 ISSN 0042-2983 107th YEAR OF PUBLICATION CONTENTS FEBRUARY 2020 ory St er ov C 11 Sri Ramakrishna: A Divine Incarnation Swami Tapasyananda 46 20 Women Saints of FEATURES Vivekananda Varkari Tradition Rock Memorial Atmarpanastuti Arpana Ghosh 8 9 Yugavani 10 Editorial Sri Ramakrishna and the A Curious Boy 18 Reminiscences Pilgrimage Mindset 27 Vivekananda Way Gitanjali Murari Swami Chidekananda 36 Special Report 51 Pariprasna Po 53 The Order on the March ck et T a le 41 25 s Sri Ramakrishna Vijayam – Poorva: Magic, Miracles Touching 100 Years and the Mystical Twelve Lakshmi Devnath t or ep R l ia c e 34 31 p S Editor: SWAMI MAHAMEDHANANDA Published by SWAMI VIMURTANANDA, Sri Ramakrishna Math, Chennai - 600 004 and Printed by B. -

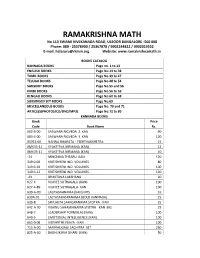

Halasuru Math Book List

RAMAKRISHNA MATH No.113 SWAMI VIVEKANADA ROAD, ULSOOR BANGALORE -560 008 Phone: 080 - 25578900 / 25367878 / 9902244822 / 9902019552 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ramakrishnamath.in BOOKS CATALOG KANNADA BOOKS Page no. 1 to 13 ENGLISH BOOKS Page No.14 to 38 TAMIL BOOKS Page No.39 to 47 TELUGU BOOKS Page No.48 to 54 SANSKRIT BOOKS Page No.55 and 56 HINDI BOOKS Page No.56 to 59 BENGALI BOOKS Page No.60 to 68 SUBSIDISED SET BOOKS Page No.69 MISCELLANEOUS BOOKS Page No. 70 and 71 ARTICLES(PHOTOS/CD/DVD/MP3) Page No.72 to 80 KANNADA BOOKS Book Price Code Book Name Rs. 002-6-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 2 KAN 90 003-4-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 3 KAN 120 05951-00 NANNA BHARATA - TEERTHAKSHETRA 15 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 12 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 10 -24 MINCHINA THEARU KAN 120 349.0-00 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 80 349.0-10 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 100 349.0-12 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 120 -43 BHAKTANA LAKSHANA 20 627-4 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALU (KAN) 100 627-4-89 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALA- KAN 100 639-A-00 LALITASAHNAMA (KAN) MYS 16 639A-01 LALTASAHASRANAMA (BOLD KANNADA) 25 639-B SRI LALITA SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN 25 642-A-00 VISHNU SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN BIG 25 648-7 LEADERSHIP FORMULAS (KAN) 100 649-5 EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE (KAN) 100 663-0-08 VIDYARTHI VIJAYA - KAN 100 715-A-00 MAKKALIGAGI SACHITRA SET 250 825-A-00 BADHUKUVA DHARI (KAN) 50 840-2-40 MAKKALA SRI KRISHNA - 2 (KAN) 40 B1039-00 SHIKSHANA RAMABANA 6 B4012-00 SHANDILYA BHAKTI SUTRAS 75 B4015-03 PHIL. -

Holy Mother Sri Sarada Devi

american vedantist Volume 15 No. 3 • Fall 2009 Sri Sarada Devi’s house at Jayrambati (West Bengal, India), where she lived for most of her life/Alan Perry photo (2002) Used by permission Holy Mother, Sri Sarada Devi Vivekananda on The First Manifestation — Page 3 STATEMENT OF PURPOSE A NOTE TO OUR READERS American Vedantist (AV)(AV) is dedicated to developing VedantaVedanta in the West,West, es- American Vedantist (AV)(AV) is a not-for-profinot-for-profi t, quarterly journal staffedstaffed solely by pecially in the United States, and to making The Perennial Philosophy available volunteers. Vedanta West Communications Inc. publishes AV four times a year. to people who are not able to reach a Vedanta center. We are also dedicated We welcome from our readers personal essays, articles and poems related to to developing a closer community among Vedantists. spiritual life and the furtherance of Vedanta. All articles submitted must be typed We are committed to: and double-spaced. If quotations are given, be prepared to furnish sources. It • Stimulating inner growth through shared devotion to the ideals and practice is helpful to us if you accompany your typed material by a CD or fl oppy disk, of Vedanta with your text fi le in Microsoft Word or Rich Text Format. Manuscripts also may • Encouraging critical discussion among Vedantists about how inner and outer be submitted by email to [email protected], as attached fi les (preferred) growth can be achieved or as part of the e mail message. • Exploring new ways in which Vedanta can be expressed in a Western Single copy price: $5, which includes U.S. -

VI. Literary Works (1950-1976)

Ramakrishna-Vedanta in Southern California: From Swami Vivekananda to the Present VI. Literary Works (1950-1976) 1. Swami Prabhavananda 2. Ida Ansell (Ujjvala) 3. Gerald Heard 4. Aldous Huxley, Alan Watts and D. T. Suzuki 5. Christopher Isherwood 6. Swami Vidyatmananda (John Yale, Prema Chaitanya) 7. Public Speakers and Film Personalities 1. Swami Prabhavananda wami Prabhavananda contributed greatly to bringing the essential message of Vedanta to the West. The sixteen books he S wrote can be grouped into five categories. A more detailed discussion of his pre-1950 works appears earlier in this book. (1) Translations of religious scripture (4): Srimad Bhagavatam: The Wisdom of God (1943); Bhagavad-Gita with C. Isherwood (1944); Crest-Jewel of Discrimination with C. Isherwood (1947); and The Upanishads: Breath of the Eternal with F. Manchester (1948). (2) Commentaries on religious scripture (3): How to Know God: The Yoga Aphorisms of Patanjali with C. Isherwood (1953); The Sermon on the Mount According to Vedanta (1963); and Narada’s Way of Divine Love: The Bhakti Sutras of Narada (1971). Prior to publication of these books, the Swami gave a series of highly praised in-depth lectures on the Sermon on the Mount and Narada’s Bhakti Sutras, as well as on the Bhagavad Gita, all of which can be purchased from Vedanta Press and Catalog. Swami Prabhavananda and Christopher Isherwood provided an invaluable service by making Eastern scripture intelligible to the Western reader. The ambiguity of many translations and commentaries had proved to be a great obstacle in spreading Vedantic ideas to readers in the West. -

The Chronology of Swami Vivekananda in the West

HOW TO USE THE CHRONOLOGY This chronology is a day-by-day record of the life of Swami Viveka- Alphabetical (master list arranged alphabetically) nanda—his activites, as well as the people he met—from July 1893 People of Note (well-known people he came in to December 1900. To find his activities for a certain date, click on contact with) the year in the table of contents and scroll to the month and day. If People by events (arranged by the events they at- you are looking for a person that may have had an association with tended) Swami Vivekananda, section four lists all known contacts. Use the People by vocation (listed by their vocation) search function in the Edit menu to look up a place. Section V: Photographs The online version includes the following sections: Archival photographs of the places where Swami Vivekananda visited. Section l: Source Abbreviations A key to the abbreviations used in the main body of the chronology. Section V|: Bibliography A list of references used to compile this chronol- Section ll: Dates ogy. This is the body of the chronology. For each day, the following infor- mation was recorded: ABOUT THE RESEARCHERS Location (city/state/country) Lodging (where he stayed) This chronological record of Swami Vivekananda Hosts in the West was compiled and edited by Terrance Lectures/Talks/Classes Hohner and Carolyn Kenny (Amala) of the Vedan- Letters written ta Society of Portland. They worked diligently for Special events/persons many years culling the information from various Additional information sources, primarily Marie Louise Burke’s 6-volume Source reference for information set, Swami Vivekananda in the West: New Discov- eries.