Ii]L 0., Carlson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Custom Book List (Page 2)

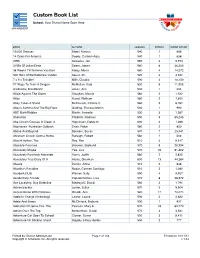

Custom Book List School: Your District Name Goes Here MANAGEMENT BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® POINTS WORD COUNT 10,000 Dresses Ewert, Marcus 540 1 688 14 Cows For America Deedy, Carmen Agra 540 1 638 2095 Scieszka, Jon 590 3 9,974 3 NBs Of Julian Drew Deem, James 560 6 36,224 38 Weeks Till Summer Vacation Kerby, Mona 580 4 14,272 500 Hats Of Bartholomew Cubbin Seuss, Dr. 520 3 3,941 7 x 9 = Trouble! Mills, Claudia 590 4 10,150 97 Ways To Train A Dragon McMullan, Kate 520 5 11,905 Aardvarks, Disembark! Jonas, Ann 530 1 334 Abbie Against The Storm Vaughan, Marcia 560 2 1,933 Abby Hanel, Wolfram 580 2 1,853 Abby Takes A Stand McKissack, Patricia C. 580 5 8,781 Abby's Asthma And The Big Race Golding, Theresa Martin 530 1 990 ABC Math Riddles Martin, Jannelle 530 3 1,287 Abduction Philbrick, Rodman 590 9 55,243 Abe Lincoln Crosses A Creek: A Hopkinson, Deborah 600 3 1,288 Aborigines -Australian Outback Doak, Robin 580 2 850 Above And Beyond Bonners, Susan 570 7 25,341 Abraham Lincoln Comes Home Burleigh, Robert 560 1 508 Absent Author, The Roy, Ron 510 3 8,517 Absolute Pressure Brouwer, Sigmund 570 8 20,994 Absolutely Maybe Yee, Lisa 570 16 61,482 Absolutely Positively Alexande Viorst, Judith 580 2 2,835 Absolutely True Diary Of A Alexie, Sherman 600 13 44,264 Abuela Dorros, Arthur 510 2 646 Abuelita's Paradise Nodar, Carmen Santiago 510 2 1,080 Accidental Lily Warner, Sally 590 4 9,927 Accidentally Friends Papademetriou, Lisa 570 8 28,972 Ace Lacewing: Bug Detective Biedrzycki, David 560 3 1,791 Ackamarackus Lester, Julius 570 3 5,504 Acquaintance With Darkness Rinaldi, Ann 520 17 72,073 Addie In Charge (Anthology) Lawlor, Laurie 590 2 2,622 Adele And Simon McClintock, Barbara 550 1 837 Adoration Of Jenna Fox, The Pearson, Mary E. -

Black Women in Primetime Soap Opera: Examining Representation Within Genre Television

Black Women in Primetime Soap Opera: Examining Representation within Genre Television by Courtney Suggs A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Media Studies Middle Tennessee State University December 2019 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Katie Foss, Chair Dr. Sanjay Asthana Dr. Sally Ann Cruikshank ABSTRACT Using textual genre analysis, this research studied representation in primetime soap operas Scandal, How To Get Away with Murder, and Empire. Two hundred and eighty- three episodes were viewed to understand how black female identity is represented in primetime soap and how genre influences those representation. Using Collins (2009) theory of controlling images, this study found that black female protagonists were depicted as jezebels and matriarchs. The welfare mother stereotype was updated by portrayals of black woman as hard working. Soap opera conventions such as heavy talk helped provide context to stereotypical portrayals while conventions such as melodrama lead to reactive characterization. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION……………………………………………….….....1 Background……………………………………………………...………........3 CHAPTER II: LITERATURE REVIEW.....................................................................9 Black Women in Scripted Television…...........................................................9 Television Effects on Viewers……………………………………………....14 CHAPTER III: THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK………………………………....18 Representation Theory……………………………………………………...18 Genre Theory……………………………………………………………….19 -

Today's Radio Programs - MONDAY WASHINGTON SAS

Today's Radio Programs - MONDAY WASHINGTON SAS. WMAL 630 WRC 9801WOL 1 2601WINX 13401WWDC1 4501WTOP 1500.- News,6, 7, 8:30 WRCAlmanac, 5:30;News,6,6:30,7,News, 6, 7,8 Hunnicutt,6.9. Corn Squeezln,530. Today's Prelude,6:05Weather Forecast. 7:30, 8; Art Brown,Hugh Guidi, Wake Devotions. 6:45, 7:30. News,6,.6:304 Town Clock,7:10, 8,6:30;News,6,7,.6:05.9. UpWith WINX, News, 6:30, 7, 7:30,7,7:30, CBSWeil 8:35.DavidWills,7:457:30,8,8:30;Bill; 6:05-9. 8:15 News, 8. !ankles Berson,5:05.9 , Sundial,7:45-9. :00BreakfastClub Katie's Daughter Musical Clock with Hews; Symphony Mike Hunnicutt Show News; Mahoney :15 DonMcNeillNancy Osgood Art Brown Chopin'sAliceLane Arthur Godfrey 9:30 Jack Owen RoadofLife SayIt LesSylphides " :45 Sam Cowling Joyce Jordan With Music Ballet Open House Home ServiceDaily; True CSrfooczer FredWaring g Open House Cecil Brown News;MusicHallI Janice Gray I Tell Your Neighbor . (Les Sands) Heritage 10::0105:30 BettyMy trackerHag.Jack Berth SpiceIn Life "" Tune inn Evelyn Winters :45ClubTime Lora Lawton (Marian Sexton) - (Norman Gladney) David Harum :00Breakfast News;To Music CliffEdwards 'Hews;Music Tune Inn News, Vern Hansel . :15 inHollywoodTo Music Musical Comedy Quiz in the Air Norman GladneyYou're theTop 11:30Ruth Crane NancyOsgood Heart's Desire "Tune Inn Grand Slam II" "II II :45 "" Tin Pan Ballet Norman Gladney Rosemary . News, Evans News; Brinkley Victor H. Lindlahr NEWSROUNDUP Tello.Test Kate Smith SpeakS :15Ted Malone Look to This Day Checkerb'd JamboreeMidday Star Time Man on the Street Aunt Jenny 12:00:30Kenny Baker ShowU. -

Montana Labor News (Butte, Mont.), 1944-08-03

THE MONTANA LABOR NEWS August 3, 1944 Page Two I M Amo# * Andy 6:00 National Pur Shop Now is the time for statesmanship. a J0 KmU MaranJ Music 6:15 Pay ’n* Save STEAKS and CHICKEN Our Specialty EDDIE'S LOUNGE 8 «S National Speaker« I jo Schwarts' Soldier» of Ifco Proos Temptingly Served THE MONTANA LABOR NEWS These next months will reveal the men of 6 45 Youth Courageous THE CASINO 7 30 Alan Young Show A PLACE WHERE UNION PUBLalSHJCD EVERT THURSDAY AT l'é -tARRlF- ’ ai8 moral stature who will speak out fear 9 >0 Now» mn 7 30 Mr LMatriot Attorney 5 Miles South of Butte on Harrison Arw. 10:00 Mr Smith Goes to Town 8 00 Kay Kyaer Catering to Private Parties MEN MEET A Fearless Champion #f Hainan tLgnts De' .ed to the lessly to the people on the basic needs of 1# 30 Three Sons Trio • 00 OhoaterflaUl WINES and LIQUORS Interest and VoictLai' Hit Demsudv <>• • IS Texaco New» Phone 70229 for Reservations Trade Ln.ori Movement. America. Men who will bring ns all back SATURDAY, AUGUST 5 9 30 Beat the Band for B * W I E A SYLVAIN, Prop 1853 llArriaoti Arena# 10 00 Ur and Mrs North foe WoodfeueT« to the unchanging moral standards that 7 30 Pay W m»UMicxi V » Texaco New* 10:30 Bob Reese Orchestra made America a democracy. Men who 1 11 Radio Classified H#adlla### w 8:30 Babe Ruth won’t be swayed by pressure, by fear of 8:45 Program Previews 9:00 On Stage Everybody ECLIPSE STORES insecurity, or by appeals to self-interest. -

Guide to Women's History Resources at the American Heritage Center

GUIDE TO WOMEN'S HISTORY RESOURCES AT THE AMERICAN HERITAGE CENTER "'You know out in Wyoming we have had woman suffrage for fifty years and there is no such thing as an anti-suffrage man in our state -- much less a woman.'" Grace Raymond Hebard, quoted in the New York Tribune, May 2, 1920. Compiled By Jennifer King, Mark L. Shelstad, Carol Bowers, and D. C. Thompson 2006 Edited By Robyn Goforth (2009), Tyler Eastman (2012) PREFACE The American Heritage Center holdings include a wealth of material on women's issues as well as numerous collections from women who gained prominence in national and regional affairs. The AHC, part of the University of Wyoming (the only university in the "Equality State") continues a long tradition of collecting significant materials in these areas. The first great collector of materials at the University, Dr. Grace Raymond Hebard, was herself an important figure in the national suffrage movement, as materials in her collection indicate. Hebard's successors continued such accessions, even at times when many other repositories were focusing their attentions on "the great men." For instance, they collected diaries of Oregon Trail travelers and accounts of life when Wyoming was even more of a frontier than it is today. Another woman, Lola Homsher, was the first formally designated University archivist and her efforts to gain materials from and about women accelerated during the service of Dean Krakel, Dr. Gene Gressley, and present director Dr. Michael Devine. As a result of this work, the AHC collections now contain the papers of pioneering women in the fields of journalism, film, environmental activism, literature, and politics, among other endeavors. -

L Today's Radio Programs

LTODAY'S RADIO PROGRAMS._____ LONDON-6:20 p. tn.= The Year's Poetry." USE, 31.5 ni., 9,51 meg.; GSD, 25.5 ni.. 11.75 meg.; GSC, 31.3 in,. 9.55 I nieg. Today's Features BERLIN-6:30 p.tn.-Good-by UntilNext Year! DID, 25.4 m., 11.77 meg. ROME-6:35 p. ra.-Opera; Recital for Piano ON W-G-N. and Violin. 2RO, 31.1 in., 9.63 meg, Melodies From the Sky, the W-G-N BERLIN-S:15 p. tn.-Songs and Verses by Stainer Maria Mike,concerthour.popular music show, will be aired DJD, 25.4 in., 11.77 meg. over the Mutual, LONDON-9:45 p. in.-" Round London al network from thei Night," London's entertainments on tap. GSD, 25.5 in.. 11.75 meg.; G3C, mainstudioat 31.3 rn. 9.58 meg.; GSA 31.5 tn., 9:30o'clockto- 0.51 meg. night,The pro- PARIS-1(1:30 p ni.-News in English. TPA4, 25.6 m., 11.72 meg, gram will be di- CHICAGO WAVE LENGTHS. rected by IIarotld W-G-N-720 WENR-870WJJ11-1130 Stokes andw;j11 W1ND-560 WAAF-920 WWAE-1200 feature Edaia WAIAQ-670 NVCFL-970 WSBC-1210 O'Dell, Lon WID3M-770 WM81-1080 1VGES-1360 WLS-870 WSI3D-10S0IV:RIP-14S0 on and Jess Kirk- patrick as8ollo- A. ists, theYiN:rar 7:00-W-G-N-Californla Sunshine. s:4s WBBAI-Musical Clock. Shades of *Blue, 1VLS-JulianBentley. the Campus choir WbfAQ-Suburban hour. 7:30-1V-G-N-The Music Box. -

Peter Alexander B

parrasch heijnen gallery 1326 s. boyle avenue los angeles, ca, 90023 www.parraschheijnen.com 3 2 3 . 9 4 3 . 9 3 7 3 Peter Alexander b. 1939 in Los Angeles, California Lives in Santa Monica, California Education 1965-66 University of California, Los Angeles, CA, M.F.A. 1964-65 University of California, Los Angeles, CA, B.A. 1963-64 University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 1962-63 University of California, Berkeley, CA 1960-62 Architectural Association, London, England 1957-60 University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA Artist in Residence 2007 Pasadena City College, Pasadena, CA 1996 California State University Long Beach, Summer Arts Festival, Long Beach, CA 1983 Sarabhai Foundation, Ahmedabad, India 1982 Centrum Foundation, Port Townsend, WA 1981 University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 1976 California State University, Long Beach, CA 1970-71 California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA Select Solo Exhibitions 2020 Peter Alexander, Parrasch Heijnen Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 2018 Peter Alexander: Recent Work, Franklin Parrasch Gallery, New York, NY Thomas Zander Gallery, Cologne, Germany 2017 Peter Alexander: Pre-Dawn L.A., Franklin Parrasch Gallery, New York, NY 2016 Peter Alexander Sculpture 1966 – 2016: A Career Survey, Parrasch Heijnen Gallery, Los Angeles, CA 2015 Los Angeles Riots, Franklin Parrasch Gallery, New York, NY 2014 Peter Blake Gallery, Laguna Beach, CA The Color of Light, Brian Gross Fine Art, San Francisco, CA Laguna Art Museum, Laguna Beach, CA 2013 Nyehaus, New York, NY Quint Contemporary Art, La Jolla, CA -

In BLACK CLOCK, Alaska Quarterly Review, the Rattling Wall and Trop, and She Is Co-Organizer of the Griffith Park Storytelling Series

BLACK CLOCK no. 20 SPRING/SUMMER 2015 2 EDITOR Steve Erickson SENIOR EDITOR Bruce Bauman MANAGING EDITOR Orli Low ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITOR Joe Milazzo PRODUCTION EDITOR Anne-Marie Kinney POETRY EDITOR Arielle Greenberg SENIOR ASSOCIATE EDITOR Emma Kemp ASSOCIATE EDITORS Lauren Artiles • Anna Cruze • Regine Darius • Mychal Schillaci • T.M. Semrad EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Quinn Gancedo • Jonathan Goodnick • Lauren Schmidt Jasmine Stein • Daniel Warren • Jacqueline Young COMMUNICATIONS EDITOR Chrysanthe Tan SUBMISSIONS COORDINATOR Adriana Widdoes ROVING GENIUSES AND EDITORS-AT-LARGE Anthony Miller • Dwayne Moser • David L. Ulin ART DIRECTOR Ophelia Chong COVER PHOTO Tom Martinelli AD DIRECTOR Patrick Benjamin GUIDING LIGHT AND VISIONARY Gail Swanlund FOUNDING FATHER Jon Wagner Black Clock © 2015 California Institute of the Arts Black Clock: ISBN: 978-0-9836625-8-7 Black Clock is published semi-annually under cover of night by the MFA Creative Writing Program at the California Institute of the Arts, 24700 McBean Parkway, Valencia CA 91355 THANK YOU TO THE ROSENTHAL FAMILY FOUNDATION FOR ITS GENEROUS SUPPORT Issues can be purchased at blackclock.org Editorial email: [email protected] Distributed through Ingram, Ingram International, Bertrams, Gardners and Trust Media. Printed by Lightning Source 3 Norman Dubie The Doorbell as Fiction Howard Hampton Field Trips to Mars (Psychedelic Flashbacks, With Scones and Jam) Jon Savage The Third Eye Jerry Burgan with Alan Rifkin Wounds to Bind Kyra Simone Photo Album Ann Powers The Sound of Free Love Claire -

Frons Launches Soap Sensation

et al.: SU Variety II SPECIAL 'GOIN' HOLLYWOOD' EDITION II NEWSPAPER Second Class P.O. Entry Supplement to Syracuse University Magazine CURTIS: IN MINIS Role Credits! "War" Series Is All-Time Screen Dream Syracuse- We couldn't pos sibly get 'em all, but in these 8 By RENEE LEVY series "Winds of War," based on to air in late spring and the entire pages find another 40-plus SU Hollywood- The longest. The Herman Wouk 's epic World War II package will air in Europe next year. alumni getting billboards on most demanding. The hardest. The novels, "War and Remembrance" Curtis, exec producer, director the boulevard. In our research, most expensive. That's the story was shot in 757 locations in 10 and co-scribe of the teleplay, spent we discovered a staggering net behind Dan Curtis 'SO's block countries, using more than 44,000 two years filming and a year and a work of Syracusans in the busi buster miniseries " War and Re actors and extras and nearly 800 half editing "War and Remem ness-producers, directors, membrance," which aired the first sets. The production- the longest brance," a project he originally actors, editors, and more! We 18 of its 30 hours in November on in television history--cost an es considered undoable-particular soon realized that all of them ABC-TV. timated $ 105 million to make. The ly because of the naval battles and would not fit, and to those left A sequel to Curtis's 1983 maxi- concluding 12 hours are expected the depiction of the Holocaust. -

Dulles Calls Red Plan for Germany Stupid

MONDAY, JANUARY 12. 1959* The Weather PA<Ste >OTratEEN Average Daily Net Press Run iim trljf0tpr lEwpning For the Week Ending Forecaurt of II.. a. Weather BoroM January 10th,' 1959 Fnlr and a bit colder tonight and St Judo Thaddeus Mothers The Queen of Peace Mothers Cir- have particlMted with Johnwn In The Officers' Wives Club of the I . Clrcle will meet Wednesday at | cle wilt meet tomorrow night all Court Slates the Towers breaks. * PRESCRIPTIONS 12,864 Wednesday. I*»w tonight 20 to 28. 93rd A A A Group will hold It* Kingalgy ha* been charged with High Wednesday In middle SO*. About Town monthly luncheon at the Head- 815 pm. at the home of Mrs. ,8:15 at the home of Mrs. Frank' DAT OR NIGHT Member of the Audit Herbert Carvev, .1 Scarborough 1 Pearaon. 110 Bretlon Rd. Tlie co-1 breakUig and entering the Pine BY EXPERTS qtiarter.s of Ihe 63rd Artillery Pharfnagy, on Center St., and the Bureau of drrulatlon I Rd. Co-hostesses will be Mrs.' hostess will be Mrs. Allyn M ar-; Manchenter— A City o f Village Charm TJi* VF\V Auxiliary will meet to- Group. New Britain, tomorrow lit Safe Break Manchester Motor Salqs, in March Thomas Sweeney and Mr*. Robert, _ ! TOontw night at T;SO at tha post 12:30 p.m. I 1954. *. ARTHUR DRUB In all. Stale Police said the four, (UlaMlIied Advertising on Page 12) PRICE FIVE CEN’1’8 home. Officer* having tmiforms are i ____ I The Nathan Hale PTA will hold Cases Jan. -

DILLON A‘ Large Section of Manhattan

dm TUESDAY, JANUARY 12, Average Dally drenUitlon 7^ The Weather For the Month of Deoember, IMS eeaat o f D. S. Weather Bu n At the meeting of Emanuel Lu 7,858 theran Brotherhood this evening Local Yontfas Complete InitiaL Training as Naval Cadets Report Hyson Oetder la Interior tonight. A bont Tow n at 8 o’clock, WiUiam Perrett will ‘Jim’ Fitzgerald Hurt Member of the Audit show several reels of colored pic Bureau o( Ofaroolattoaa M VDttnf BMmlMn O t Bmkiniel tures taken during his travels In War Prisoner Manchester^A City of Village Charm l^rthwanraurcli • » requested to the W est All men of the church will be welcome. ‘ ^As U. S. Cruiser Smki n c a m tiM hour of 3:30 p. n., .(Chwalled Advertlalng ou Page 14) MANCHESTER, CONN„ WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 13, 1943 (SIXTEEN PAGES) PRICE THREE CENTS M tt Smutay. wh«i Former Local Youth VOL. LXII., NO. 88 aMottnc e t ^ ctaurch will take Mr. and M rs.^ llia m Ostrinsky of Blssell street received a tele Captured by Japanese Parents Notified He Is January of last year and was alsd plMSi gram last ntfht Informing them assigned to the Juneau after coml In Philippine Battle. pletlng his training. Hla w ifi H w Brnblem club will meet to- that their/son. Sergt Abraham In Hospital Enroute U. S. Doughboy Covers Burning German Tank Ostrinsky Is ill at the Greenville last received word from him la m is'rpw aftamoon at 3:30 .at the To U. S.; Another November. This was writtea pniM home in Rockville. -

Guide to Women's History Collections

GUIDE TO WOMEN'S HISTORY RESOURCES AT THE AMERICAN HERITAGE CENTER "'You know out in Wyoming we have had woman suffrage for fifty years and there is no such thing as an anti-suffrage man in our state -- much less a woman.'" Grace Raymond Hebard, quoted in the New York Tribune, May 2, 1920. Compiled By Jennifer King, Mark L. Shelstad, Carol Bowers, and D. C. Thompson 2006 Edited By Robyn Goforth (2009), Tyler Eastman (2012) PREFACE The American Heritage Center holdings include a wealth of material on women's issues as well as numerous collections from women who gained prominence in national and regional affairs. The AHC, part of the University of Wyoming (the only university in the "Equality State") continues a long tradition of collecting significant materials in these areas. The first great collector of materials at the University, Dr. Grace Raymond Hebard, was herself an important figure in the national suffrage movement, as materials in her collection indicate. Hebard's successors continued such accessions, even at times when many other repositories were focusing their attentions on "the great men." For instance, they collected diaries of Oregon Trail travelers and accounts of life when Wyoming was even more of a frontier than it is today. Another woman, Lola Homsher, was the first formally designated University archivist and her efforts to gain materials from and about women accelerated during the service of Dean Krakel, Dr. Gene Gressley, and present director Dr. Michael Devine. As a result of this work, the AHC collections now contain the papers of pioneering women in the fields of journalism, film, environmental activism, literature, and politics, among other endeavors.