Magnitude, Composition and Spatiotemporal Patterns of Vertebrate Roadkill at Regional Scales: a Study in Southern Spain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abstract Book Progeo 2Ed 20

Abstract Book BUILDING CONNECTIONS FOR GLOBAL GEOCONSERVATION Editors: G. Lozano, J. Luengo, A. Cabrera Internationaland J. Vegas 10th International ProGEO online Symposium ABSTRACT BOOK BUILDING CONNECTIONS FOR GLOBAL GEOCONSERVATION Editors Gonzalo Lozano, Javier Luengo, Ana Cabrera and Juana Vegas Instituto Geológico y Minero de España 2021 Building connections for global geoconservation. X International ProGEO Symposium Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación Instituto Geológico y Minero de España 2021 Lengua/s: Inglés NIPO: 836-21-003-8 ISBN: 978-84-9138-112-9 Gratuita / Unitaria / En línea / pdf © INSTITUTO GEOLÓGICO Y MINERO DE ESPAÑA Ríos Rosas, 23. 28003 MADRID (SPAIN) ISBN: 978-84-9138-112-9 10th International ProGEO Online Symposium. June, 2021. Abstracts Book. Editors: Gonzalo Lozano, Javier Luengo, Ana Cabrera and Juana Vegas Symposium Logo design: María José Torres Cover Photo: Granitic Tor. Geosite: Ortigosa del Monte’s nubbin (Segovia, Spain). Author: Gonzalo Lozano. Cover Design: Javier Luengo and Gonzalo Lozano Layout and typesetting: Ana Cabrera 10th International ProGEO Online Symposium 2021 Organizing Committee, Instituto Geológico y Minero de España: Juana Vegas Andrés Díez-Herrero Enrique Díaz-Martínez Gonzalo Lozano Ana Cabrera Javier Luengo Luis Carcavilla Ángel Salazar Rincón Scientific Committee: Daniel Ballesteros Inés Galindo Silvia Menéndez Eduardo Barrón Ewa Glowniak Fernando Miranda José Brilha Marcela Gómez Manu Monge Ganuzas Margaret Brocx Maria Helena Henriques Kevin Page Viola Bruschi Asier Hilario Paulo Pereira Carles Canet Gergely Horváth Isabel Rábano Thais Canesin Tapio Kananoja Joao Rocha Tom Casadevall Jerónimo López-Martínez Ana Rodrigo Graciela Delvene Ljerka Marjanac Jonas Satkünas Lars Erikstad Álvaro Márquez Martina Stupar Esperanza Fernández Esther Martín-González Marina Vdovets PRESENTATION The first international meeting on geoconservation was held in The Netherlands in 1988, with the presence of seven European countries. -

A Behavior-Based Framework for Assessing Barrier Effects to Wildlife from Vehicle Traffic Volume 1 Sandra L

CONCEPTS & THEORY A behavior-based framework for assessing barrier effects to wildlife from vehicle traffic volume 1 Sandra L. Jacobson,1,† Leslie L. Bliss-Ketchum,2 Catherine E. de Rivera,2 and Winston P. Smith3,4 1 1USDA Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station, Davis, California 95618 USA 1 2Department of Environmental Science & Management, School of the Environment, 1 Portland State University, Portland, Oregon 97207-0751 USA 1 3USDA Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, La Grande, Oregon 97850 USA 1 Citation: Jacobson, S. L., L. L. Bliss-Ketchum, C. E. de Rivera, and W. P. Smith. 2016. A behavior-based framework for assessing barrier effects to wildlife from vehicle traffic volume. Ecosphere 7(4):e01345. 10.1002/ecs2.1345 Abstract. Roads, while central to the function of human society, create barriers to animal movement through collisions and habitat fragmentation. Barriers to animal movement affect the evolution and tra- jectory of populations. Investigators have attempted to use traffic volume, the number of vehicles passing a point on a road segment, to predict effects to wildlife populations approximately linearly and along taxonomic lines; however, taxonomic groupings cannot provide sound predictions because closely related species often respond differently. We assess the role of wildlife behavioral responses to traffic volume as a tool to predict barrier effects from vehicle-caused mortality and avoidance, to provide an early warning system that recognizes traffic volume as a trigger for mitigation, and to better interpret roadkill data. We propose four categories of behavioral response based on the perceived danger to traffic: Nonresponders, Pausers, Speeders, and Avoiders. -

Module 6. Hov Treatments

Manual TABLE OF CONTENTS Module 6. TABLE OF CONTENTS MODULE 6. HOV TREATMENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 6.1 INTRODUCTION ............................................ 6-5 TREATMENTS ..................................................... 6-6 MODULE OBJECTIVES ............................................. 6-6 MODULE SCOPE ................................................... 6-7 6.2 DESIGN PROCESS .......................................... 6-7 IDENTIFY PROBLEMS/NEEDS ....................................... 6-7 IDENTIFICATION OF PARTNERS .................................... 6-8 CONSENSUS BUILDING ........................................... 6-10 ESTABLISH GOALS AND OBJECTIVES ............................... 6-10 ESTABLISH PERFORMANCE CRITERIA / MOES ....................... 6-10 DEFINE FUNCTIONAL REQUIREMENTS ............................. 6-11 IDENTIFY AND SCREEN TECHNOLOGY ............................. 6-11 System Planning ................................................. 6-13 IMPLEMENTATION ............................................... 6-15 EVALUATION .................................................... 6-16 6.3 TECHNIQUES AND TECHNOLOGIES .................. 6-18 HOV FACILITIES ................................................. 6-18 Operational Considerations ......................................... 6-18 HOV Roadway Operations ...................................... 6-20 Operating Efficiency .......................................... 6-20 Considerations for 2+ Versus 3+ Occupancy Requirement ............. 6-20 Hours of Operations .......................................... -

Evaluating Mitigation Plans Over Traffic Sector to Improve NO2 Levels in Andalusia (Spain) Using a Regional-Local Scale Photochemical Modelling System

Open Journal of Air Pollution, 2014, 3, 70-86 Published Online September 2014 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojap http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojap.2014.33008 Evaluating Mitigation Plans over Traffic Sector to Improve NO2 Levels in Andalusia (Spain) Using a Regional-Local Scale Photochemical Modelling System Raúl Arasa1, Antonio Lozano-García2, Bernat Codina1,3 1Air Quality Department, Meteosim S.L., Barcelona, Spain 2Environment and Water Agency of Andalusia, Seville, Spain 3Department of Astronomy and Meteorology, Barcelona, Spain Email: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Received 5 August 2014; revised 1 September 2014; accepted 17 September 2014 Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract In this contribution, we present an evaluation of different mitigation plans to improve NO2 levels in Andalusia, a region in the south of Spain. Specifically, we consider four possible mitigation plans: the effects over NO2 concentration of apply changes in the distribution of Vehicles Park; the effect of realize traffic restrictions (affecting to the density flow of vehicles) over highways and main roads; the effect of replacement of diesel use by natural gas in urban areas; and the effect of ap- plying new velocity limits to access to urban areas. A sophisticated air quality modelling (AQM) system has been used to evaluate these mitigation plans. AQM implemented is composed on WRF meteorological model, an emission model created by the authors and CMAQ photochemical model. AQM analyzes mitigation plans during fifteen episodes of 2011 where NO2 levels were the highest of the year; so we analyze the effect of mitigation plans in worst conditions. -

Shared Streets and Alleyways – White Paper

City of Ashland, Ashland Transportation System Plan Shared Streets and Alleyways – White Paper To: Jim Olson, City of Ashland Cc: Project Management Team From: Adrian Witte and Drew Meisel, Alta Planning + Design Date: February 2, 2011 Re: Task 7.1.O White Paper: “Shared Streets and Alleyways” - DRAFT Direction to the Planning Commission and Transportation Commission Five sets of white papers are being produced to present information on tools, opportunities, and potential strategies that could help Ashland become a nationwide leader as a green transportation community. Each white paper will present general information regarding a topic and then provide ideas on where and how that tool, strategy, and/or policy could be used within Ashland. You will have the opportunity to review the content of each white paper and share your thoughts, concerns, questions, and ideas in a joint Planning Commission/Transportation Commission meeting. Based on discussions at the meeting, the material in the white paper will be: 1) Revised and incorporated into the alternatives analysis for the draft TSP; or 2) Eliminated from consideration and excluded from the alternatives analysis. The overall intent of the white paper series is to explore opportunities and discuss the many possibilities for Ashland. Shared Streets Introduction Shared Streets aim to provide a better balance of the needs of all road users to improve safety, comfort, and livability. They are similar to European concepts such as the Dutch based ‘Woonerf’ and the United Kingdom’s ‘Home Zone’, with some distinct differences. This balance is accomplished through integration rather than segregation of users. By eschewing many of the traditional roadway treatments such as curbs, signs, and pavement markings, the distinction between modes is blurred. -

Reversible Traffic Lanes

Traffic Management System Efficiency Reversible Traffic Lanes REVERSIBLE TRAFFIC LANES Description Reversible traffic lanes add capacity to a road and decrease congestion by borrowing capacity from the other (off- peak) direction. Reversing lanes reduces congestion during morning and evening commutes, when there is an incident blocking a lane of traffic, or when construction or maintenance is being done on the road. Roads can be adjusted to become a one- way street or have one middle lane operate in the peak direction. These adjustments, indicated by changeable message signs and/or Cost: arrows, occur at specified times of the day or when volume Time: Short exceeds certain limits. Impact: Corridor Target Market Who: City/State . Congested work zone areas or during incidents Hurdles: Public Awareness/ . Roads with highly directional congestion Operation . Bridges, tunnels, and toll booth areas difficult to widen . Surrounding or leading to/from special event centers Reversible lanes work well in corridors where traffic flow is heavily imbalanced for a short period of time, and there are few other solution options. How Will This Help? . Reduce congestion by temporarily “borrowing” capacity from the other direction. Increase safety in work zones. Postpone the need to add capacity through conventional lane additions. Implementation Issues Success Story Proper communication and public participation are crucial to Arlington, Texas, installed reversible ensuring the strategy’s success. Local agencies should identify lanes to mediate congestion around two the best locations for implementation and ensure the public and professional sports stadiums agencies understand the concept and operation. The endpoint . FM 157/Collins Street treatment requires particular care and attention—common . -

What Are the Advantages of Roundabouts?

What is a roundabout? A roundabout is an intersection where traffic travels around a Circulatory central island in a counter- Truck Apron Roadway clockwise direction. Vehicles entering or exiting the roundabout must yield to vehicles, bicyclists, and pedestrians. Figure 1 presents the elements of a roundabout. Yield Line Splitter Island Figure 1: Elements of a Roundabout What are the advantages of roundabouts? • Less Traffic Conflict: Figure 2 compares the conflict points between a conventional intersection and a modern roundabout. The lower number of conflict points translates to less potential for accidents. • Greater safety(1): Primarily achieved by slower speeds and elimination of left turns. Design elements of the roundabouts cause drivers to reduce their speeds. • Efficient traffic flow: Up to 50% increase in traffic capacity • Reduced Pollution and fuel usage: Less stops, shorter queues and no left turn storage. • Money saved: No signal equipment to install or maintain, plus savings in electricity use. • Community benefits: Traffic calming and enhanced aesthetics by landscaping. (1) Statistics published by the U.S. Dept. of transportation, Federal Highway Administration shows roundabouts to have the following advantages over conventional intersections: • 90% reduction in fatalities • 76% reduction in injuries • 35% reduction in pedestrian accidents. Signalized Intersection Roundabout Figure 2: Conflict Point Comparison How to Use a Roundabout Driving a car • Slow down as you approach the intersection. • Yield to pedestrians and bicyclists crossing the roadway. • Watch for signs and pavement markings. • Enter the roundabout if gap in traffic is sufficient. • Drive in a counter-clockwise direction around the roundabout until you reach your exit. Do not stop or pass other vehicles. -

Rules for Driving Roundabouts

RULES FOR DRIVING ROUNDABOUTS www.wisconsinroundabouts.gov General information for all roundabouts Steps for driving a roundabout: Roundabouts are becoming more common 1. Slow down. Obey traffic signs. in the U.S. because they provide safer and 2. Yield to pedestrians and bicyclists. more efficient traffic flow than standard 3. Yield to traffic on your left intersections. By keeping traffic moving one-way already in the roundabout. in a counterclockwise direction, there are fewer 4. Enter the roundabout when conflict points and traffic flows smoothly. there is a safe gap in traffic. Crash statistics show that roundabouts 5. Keep your speed low reduce fatal crashes about 90%, reduce within the roundabout. injury crashes about 75%, and reduce overall 6. As you approach your exit, crashes about 35%, when compared Draft 5 February 2, 2009 turn on your right turn signal. to other types of intersection control. 7. Yield to pedestrians and When driving a roundabout, the same bicycles as you exit. general rules apply as for maneuvering Emergency vehicles in the roundabout through any other type of intersection. P Always yield to emergency vehicles. Truck apron P If you have not entered the roundabout, pull Large vehicles need more space when driving over and allow emergency vehicles to pass. in a roundabout. A truck apron is a paved area P If you have entered the roundabout, on the inside of the roundabout for the rear wheels continue to your exit, then pull over of large trucks to use when turning, sometimes and allow emergency vehicles to pass. referred to as off-tracking. -

Real Federación Española De Atletismo Departamento De Medios

Real Federación Española de Atletismo Departamento de Medios de Comunicación y RR.PP. Tel. 915487863 Página Web: http://www.rfea.es – Correo electrónico: [email protected] Av. Valladolid, 81, 1º - 28008 Madrid – Fax:915476113 / 915480638 Nota de Prensa - 090/2003 - Madrid, 11 de julio de 2003 SUPER GRAND PRIX “MADRID’2012” MÁS ESTRELLAS PARA EL SUPER GRAND PRIX “MADRID’2012” Durante el fin de semana que hoy comienza seguro que se producen importantes novedades de cara a la participación en el Super Grand Prix “Madrid’2012” del día 19 en el Estadio de Madrid. Estas importantes novedades, así como la lista completa de participantes y otros detalles organizativos, quedarán desveladas en la rueda de prensa que José Mª Odriozola -Presidente de la RFEA- y Feliciano Mayoral -Consejero Delegado de Madrid’2012- ofrecerán en el martes día 15 a las 13,00 horas en el salón Edimburgo del Hotel NH Eurobuilding, sito en la calle Padre Damián nº 23 de Madrid. En cualquier caso, a los nombres ya avanzados –los especialistas en saltos y lanzamientos- la organización ya ha cerrado la presencia de destacados velocistas, mediofondistas y vallistas, como es el caso de los siguientes atletas. Frank Frederiks, un gigante de la velocidad, contra Francis Obikwelu El namibio Frank Frederiks, dos veces campeón del Mundo de 200 m.l. – en 1999 bajo techo y en 1993 al aire libre- tres veces subcampeón mundial (1991, 1995 y 1997) y doble subcampeón olímpico en barcelona’92 y Atlanta’96 tanto en 100 como en 200 m.l., es una de las estrellas de la velocidad que competirá el Estadio de la Peineta. -

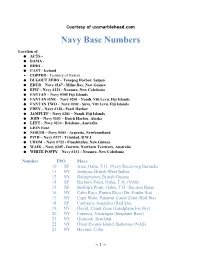

Navy Base Numbers

Courtesy of ussmarblehead.com Navy Base Numbers Location of: ACTS - BAMA - BIHO - CAST - Iceland COPPER - Territory of Hawaii DUGOUT ZERO – Tenapag Harbor, Saipan EDUR – Navy #167 - Milne Bay, New Guinea EPIC - Navy #131 - Noumea, New Caledonia FANTAN – Navy #305 Fiji Islands FANTAN ONE - Navy #201 - Nandi, Viti Levu, Fiji Islands FANTAN TWO - Navy #202 - Suva, Viti Levu, Fiji Islands FREY – Navy #128 - Pearl Harbor JAMPUFF – Navy #201 – Nandi, Fiji Islands JOIN – Navy #151 – Dutch Harbor, Alaska LEFT – Navy #134 - Brisbane, Australia LION Four NORTH – Navy #103 - Argentia, Newfoundland PITH – Navy #117 - Trinidad, B.W.I. UROM – Navy #722 - Finschhafen, New Guinea WAIK – Navy #245 - Darwin, Northern Territory, Australia WHITE POPPY – Navy #131 - Noumea, New Caledonia Number FPO Place 10 SF Aiea, Oahu, T.H. (Navy Receiving Barracks 11 NY Antigua, British West Indies 12 NY Georgetown, British Guiana 14 SF Barber's Point, Oahu, T.H. (NAS) 15 SF Bishop's Point, Oahu, T.H. (Section Base) 16 NY Cabo Rojo, Puerto Rico (Dir. Finder Sta) 17 NY Cape Mala, Panama, Canal Zone (Rad Sta) 18 SF Canberra, Australia (Rad Sta) 19 NY David, Canal Zone (Landplane Facility) 20 NY Fonseca, Nicaragua (Seaplane Base) 21 NY Gourock, Scotland 22 NY Great Exuma Island, Bahamas (NAS) 23 NY Havana, Cuba ~ 1 ~ Courtesy of ussmarblehead.com 24 SF Hilo, Hawaii, T.H. (Section Base) 25 NY Hvalfjordur, Iceland (Navy Depot) 26 NY Ivigtut, Greenland (Nav Sta--later, Advance Base) 27 SF Kahului, Maui, T.H. (Section Base) 28 SF Kaneohe, Oahu, T.H. (NAS) 29 SF Keehi Lagoon, Honolulu, T.H. (NAS) 30 SF Puunene, Maui, T.H. -

Public Correspondence Item 7- Oppose

Public Correspondence 1 of 267 Item 7- Oppose ADAMS BROADWELL JOSEPH & CARDOZO A PROFESSIONAL CORPORATION SO. SAN FRANCISCO OFFICE DANIEL L. CARDOZO CHRISTINA M. CARO ATTORNEYS AT LAW THOMAS A. ENSLOW 601 GATEWAY BLVD., SUITE 1000 SO. SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94080 ANDREW J. GRAF 520 CAPITOL MALL, SUITE 350 TANYA A. GULESSERIAN SACRAMENTO, CA 95814 - 4721 TEL: (650) 589 - 1660 KENDRA D. HARTMANN* ___________ FAX: (650) 589 - 5062 KYLE C. JONES RACHAEL E. KOSS TEL: (916) 444 - 6201 NIRIT LOTAN FAX: (916) 444 - 6209 WILLIAM C. MUMBY [email protected] MARC D. JOSEPH Of C ounsel November 11, 2020 *Not admitted in California. Lic ensed in Colorado. Via Email and U.S. Mail Chair Douglas Barnhart and Planning Commissioners Planning Commission County of San Diego Planning & Development Services 5510 Overland Avenue, Suite 110 San Diego, CA 92123 Email: [email protected] Re: Comments on the Final Environmental Impact Report for the Boulder Brush Facilities (SCH No. 2019029094, PDS2019-ER-19- 16-001, PDS 2019-MUP-19-002) Dear Chair Barnhart and Planning Commissioners: We are writing on behalf of Citizens for Responsible Wind Energy (“Citizens”) and Doyle Mills to provide comments on the County of San Diego’s (“County”) September 2020 Final Environmental Impact Report (“FEIR”), prepared pursuant to the California Environmental Quality Act (“CEQA”),1 for Terra-Gen Development Company LLC’s (“Terra-Gen”) proposed Campo Wind Project with Boulder Brush Facilities (“Project”).2 The FEIR incorporates by reference a May 2019 Draft Environmental Impact Statement (“DEIS”) prepared by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (“BIA”), pursuant to the National Environmental Policy Act. -

Andalucía Flamenca: Music, Regionalism and Identity in Southern Spain

Andalucía flamenca: Music, Regionalism and Identity in Southern Spain A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology by Matthew Machin-Autenrieth © Matthew Machin-Autenrieth 2013 Tables of Contents Table of Contents i List of Plates iv List of Examples iv List of Figures v Conventions vi Acknowledgments viii Abstract x Introduction 1 PART ONE Chapter One: An Overview of Flamenco 6 The Identities of Flamenco 9 The Materials of Flamenco 12 The Geographies of Flamenco 19 The Scholars of Flamenco 25 Chapter Two: Music, Regionalism and Political Geography 36 Political Geography and Music 37 Region, Regionalisation and Regionalism 43 Regionalism and Music 51 The Theoretical Framework 61 Conclusions 68 Chapter Three: Methodology 70 Virtual Ethnography: In Theory 70 Virtual Ethnography: In Practice 79 Field Research in Granada 86 Conclusions 97 Chapter Four: Regionalism, Nationalism and Ethnicity in the History of Flamenco 98 Flamenco and the Emergence of Andalucismo (1800s–1900s) 99 Flamenco and the Nation: Commercialisation, Salvation and Antiflamenquismo 113 Flamenco and Political Andalucismo (1900–1936) 117 Flamenco during the Franco Regime (1939–75) 122 Flamenco since the Transition to Democracy (1975 onwards) 127 Conclusions 131 i Chapter Five: Flamenco for Andalusia, Flamenco for Humanity 133 Flamenco for Andalusia: The Statute of Autonomy 134 Flamenco for Humanity: Intangible Cultural Heritage 141 The Regionalisation of Flamenco in Andalusia 152 Conclusions 169 PART