Emma Webster

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Felix Issue 1103, 1998

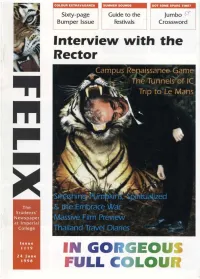

COLOUR EXTRAVAGANZA SUMMER SOUNDS GOT SOME SPARE TIME? Sixty-page Guide to the Jumbo $f Bumper Issue Festivals Crossword Interview with the Rector Campus Renaissance Game y the Tunnels "of IC 1 'I ^ Trip to Le Mans 7 ' W- & the Embrace War Massive Film Preview Thailand Travel Diaries IN GO EOUS FULL C 4 2 GAME 24 June 1998 24 June 1998 GAME 59 Automatic seating in Great Hall opens 1 9 18 unexpectedly during The Rector nicks your exam, killing fff parking space. Miss a go. Felix finds out that you bunged the builders to you're fc Rich old fo work Faster. "start small antiques shop. £2 million. Back one. ii : 1 1 John Foster electro- cutes himself while cutting IC Radio's JCR feed. Go »zzle all the Forward one. nove to the is. The End. P©r/-D®(aia@ You Bung folders to TTafeDts iMmk faster. 213 [?®0B[jafi®Drjfl 40 is (SoOOogj® gtssrjiBGariy tsm<s5xps@G(§tlI ITCD® esiDDorpo/Js Bs a DDD®<3CM?GII (SDB(Sorjaai„ (pAsasamG aracil f?QflrjTi@Gfi®OTjaD Y®E]'RS fifelaL rpDaecsS V®QO wafccs (MJDDD Haglfe G® sGairGo (SRBarjDDo GBa@to G® §GapG„ i You give the Sheffield building a face-lift, it still looks horrible. Conference Hey ho, miss a go. Office doesn't buy new flow furniture. ir failing Take an extra I. Move go. steps back. start Place one Infamou chunk of asbestos raer shopS<ee| player on this square, », roll a die, and try your Southsid luck at the CAMPUS £0.5 mil nuclear reactor ^ RENAISSANCE GAME ^ ill. -

1) the Beatles Are More Popular Today Than Ever

Variant 2 READING TEXT 1 1. Read the article and decide if the statements (1 10) are True (T) or False (F). 1) The Beatles are more popular today than ever. 2) The 3) 4) There is a Beatles Festival every year in the USA. 5) Paul McCartney lived in Penny Lane when he was a teenager. 6) Penny Lane is in Liverpool. 7) The Beatles always wrote their own songs. 8) In Britain, the Beatles are forgotten. 9) Not many people go to Liverpool every year, to see where it all began. 10) They became popular because they caught the spirit of a generation. THE BEATLES STILL GOING STRONG Although they broke up almost 50 years ago, the Beatles are still one of the most popular rock groups in the world! During the six years of their ex- istence, they led a revolution in music. Half a century later, their records still sell in millions every year. In 2014, Hollywood is making a big new documentary film about the Beatles.... almost 50 years after they broke up! I On air live at the BBC part 2 was s 31st top album in the USA! In 1996, six million Beatles albums were sold during the year. That would be a good score for a functioning band or group; but for a group that last played together in 1970, it was incredible! In Britain, a study recently showed that the Beatles are still one of the most popular groups with people over 15 years old; and they are still popular with teenagers too. -

Britpop 1 a Free Quiz About the Music and the Musicians Associated with Britpop

Copyright © 2021 www.kensquiz.co.uk Britpop 1 A free quiz about the music and the musicians associated with Britpop. 1. Which journalist and DJ was credited for first using the term "Britpop" in 1993? 2. Which Oasis single provided them with their first UK number one in April 1995? 3. Gaz Coombes was the guitarist and lead singer of which 90s band? 4. The Verve's "Bittersweet Symphony" samples an orchestral version of which Rolling Stones hit? 5. Which Pulp album featured the single "Common People"? 6. Brett Anderson was the lead singer of which Britpop band? 7. What was the title of The Boo Radley's only UK top ten single? 8. In which northern city were Shed Seven formed in 1990? 9. Which song by Ocean Colour Scene was used by Chris Evans to introduce his guests on TFI Friday? 10. What was the original name of Britpop band Blur? 11. A founding member of Suede, which female fronted the band Elastica? 12. "Smart" was the debut album of which band? 13. Which band received the inaugural NME Brat Award for Best New Act in 1995? 14. Who sang alongside Space on their 1998 top five single "The Ballad of Tom Jones"? 15. Which single of 1991 gave Blur their first UK top ten hit? 16. Released in 1995, what was the title of Cast's debut album? 17. What was the name of the 90's band fronted by radio personality Laureen Laverne? 18. The 1996 single "Good Enough" was the only UK top ten hit for which band? 19. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Box London www.karaokebox.co.uk 020 7329 9991 Song Title Artist 22 Taylor Swift 1234 Feist 1901 Birdy 1959 Lee Kernaghan 1973 James Blunt 1973 James Blunt 1983 Neon Trees 1985 Bowling For Soup 1999 Prince If U Got It Chris Malinchak Strong One Direction XO Beyonce (Baby Ive Got You) On My Mind Powderfinger (Barry) Islands In The Stream Comic Relief (Call Me) Number One The Tremeloes (Cant Start) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue (Doo Wop) That Thing Lauren Hill (Everybody's Gotta Learn Sometime) I Need Your Loving Baby D (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Bryan Adams (Hey Wont You Play) Another Somebody… B. J. Thomas (How Does It Feel To Be) On Top Of The World England United (I Am Not A) Robot Marina And The Diamonds (I Love You) For Sentinmental Reasons Nat King Cole (If Paradise Is) Half As Nice Amen Corner (Ill Never Be) Maria Magdalena Sandra (I've Had) The Time Of My Life Bill Medley and Jennifer Warnes (Just Like) Romeo And Juliet The Reflections (Just Like) Starting Over John Lennon (Keep Feeling) Fascination The Human League (Maries The Name) Of His Latest Flame Elvis Presley (Meet) The Flintstones B-52S (Mucho Mambo) Sway Shaft (Now and Then) There's A Fool Such As I Elvis Presley (Sittin On) The Dock Of The Bay Otis Redding (The Man Who Shot) Liberty Valance Gene Pitney (They Long To Be) Close To You Carpenters (We Want) The Same Thing Belinda Carlisle (Where Do I Begin) Love Story Andy Williams (You Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1 2 3 4 (Sumpin New) Coolio 1 Thing Amerie 1+1 (One Plus One) Beyonce 1000 Miles Away Hoodoo Gurus -

Chantel Mcgregor at the Cluny Hardwick Live Leeds

WWW.NEVOLUME.CO.UK LINDISFARNE FESTIVAL 2017 WE’RE LISTENING! The Libertines At Times Square Hardwick Live ISSUE #25 Hartlepool Waterfront Festival Leeds Festival AUG 2017 FOLLOW We speak to Velvoir as they play Chantel McGregor NE VOLUME ON SOCIAL NE Volume Live at ARC at The Cluny MEDIA Artist Spotlight: JustSo Mousetival PICK UP OUR FREE NORTH EAST MUSIC/CULTURE MAGAZINE! LET’S GET EVEN LOUDER NORTH EAST VOLUME!!!!! NEWS! FEATURES! WELCOME! Thank you so much for picking up PG.5 Gig Preview: PG.21 Billingham International Folklore The Libertines at Times Square, Festival Of World Dance - NE Volume magazine - the magazine Newcastle! Peacock Lake! produced by local music and culture fans, for local music and culture fans. So we’re Mousetival! PG.6 Festival Preview: PG.22 right in the middle of festival season! You Howzat Music Festival, Saltburn! PG.24 Leeds Festival 2017! may have already been to Glastonbury this year, or a local festival such as PG.7 Gig Preview: PG.25 Hardwick Live 2017! Willowman or Sunniside Live, but you’ll Plaza at The House Of Blah Blah, be glad to know there are even more Middesbrough! PG.28 Lindisfarne Festival 2017! taking place in the region this month. Anyhow, moving on, in this month’s PG.10 Gig Preview: INTERVIEWS! edition we chat to Ocean Colour Scene Chantel McGregor at The Cluny, as they prepare to play Hardwick Live; Newcastle! PG.33 The Fratellis! we provide you with our honest opinion of Carl Barat and the Jackals at KU Bar, PG.11 Gig Preview: PG.34 Roddy Woomble! Hivemind at The Independent, Stockton; we keep you up-to-date with Sunderland! PG.35 Velvoir! what’s happening in the region this month including: The Libertines at Times Square PG.38 Ocean Colour Scene! in Newcastle, Mousetival at the Georgian Theatre in Stockton and Plaza at The PG.40 Rojor! CULTURE CORNER! House of Blah Blah in Middlesbrough; in our culture section we provide you with PG.14 Comedy: Laura Lezz + Ben Crompton GIG REVIEWS! details of Hartlepool Waterfront Festival, and so much more. -

Let It Be Liverpool

THE 4 LETBEATS IT BE LIVERPOOL 25th AUGUST - 31st AUGUST - - 2021 COME TOGETHER BECAUSE ALL THINGS MUST PASS Nicolás Gonzalez was born in 1980. When he was 8 years old, he heard Love Me Do at a party and his life changed forever! He fell in love with The Beatles and knew that music would be his life. For years, he bought and assembled a collection of Beatles instruments with the idea of one day forming a tribute band. In 2016 he met Bruno (drummer) through a friend and invited him to join the band. Then Bruno invited three other friends who played with him in another band (Martin, Bruno and Agustin). When the band finally formed in 2016, they began to perform in different stages and bars in Montevideo. At the end of 2016 they competed in the Beatle Week battle of the bands at The Cavern in Buenos Aires, reaching the final, and in 2017 they decided to take the leap and present a show in one of the great theaters of Montevideo in which they recreated chronologically the music of The Beatles. HUNTER DAVIES ANDY NEWMARK MARK McGANN At the end of 2017 they returned to Beatle Week in Buenos Aires returning to be JULIAamong BAIRD the five HOWIEfinalists, CASEY subsequently PURE beingMcCARTNEY invited to International CAVERN CLUB Beatleweek BEATLES by GERRYBill Heckle ACROSS as one THE of two MERSEY runner-up 1970-1971 places. CLASSIC ALBUMS CAVERN CLUB BEATLES CONVENTION THE JACARANDA REMEMBERING JOHN & GEORGE 1 WWW.INTERNATIONALBEATLEWEEK.COMWWW.INTERNATIONALBEATLEWEEK.COM WWW.INTERNATIONALBEATLEWEEK.COM THEWELCOME... 4 BEATS Welcome...‘Come Together Because All Things Must Pass’. -

BRITISH BEATLES FAN CLUB MAGAZINES - Jetzt Auch in Deutschland Erhältlich, Natürlich Im Beatles Museum … Einzelheft: 4,50 Euro Inkl

InfoMail 18.07.15: Die BRITISH BEATLES FANCLUB-Magazine /// MANY YEARS AGO InfoMails abbestellen oder umsteigen (täglich, wöchentlich oder monatlich): Nur kurze Email schicken. Hallo M.B.M.! Hallo BEATLES-Fan! BRITISH BEATLES FAN CLUB MAGAZINES - jetzt auch in Deutschland erhältlich, natürlich im Beatles Museum … Einzelheft: 4,50 Euro inkl. Versand 10er Abo: 40,00 Euro inkl. Versand für aktuelles Heft und die nächsten neun. Weitere Info und/oder bestellen: Einfach Abbildung anklicken Auch Abbildungen in pdf-Datei anklickbar. Ausgaben 55 bis 53 - Jedes Heft 4,50 Euro inkl. Versand Juni 2015: BEATLES-Fanmagazin BRITISH BEATLES FAN CLUB MAGAZINE - ISSUE 55. Heft; Hochformat: A5; 40 Seiten; viele Farb- und Schwarzweiß-Fotos; englischsprachig. Inhalt: cover photo: 1970 - JOHN LENNON. / Editorial. / THE BEATLES - A Day in the Life. / Media Watch. / Coming Up - Forthcoming Events incl. PAUL McCARTNEY's OUT THERE! 2015 USA & EUROPE and RINGO STARR & HIS ALL-STARR BAND TOUR 2015. / CYNTHIA LENNON 1939 - 2015 - "Just smile and love but don't cry". / RINGO STARR & HIS ALL-STARR BAND TOUR 2015: 1st March 2015 - Planetario Galileo Galilei, Buenos Aires, Argentina. / PAUL McCARTNEY's OUT THERE!: 28th April 2015 - Nihon Budokan Hall, Tokyo, Japan; 23rd May 2015 - O2 Arena, London, UK; 24th May 2015 - O2 Arena, London, UK. / Paperback Writers: BEST OF THE BEATLES - THE SACKING OF PETE BEST: THE BEATLES THROUGH HEADPHONES; JOHN LENNON - THE COLLECTED ARTWORK; CONFESSIONS OF BEATLEMANIAC; WINGS OVER NEW ORLEANS; MY KID BROTHER'S BAND A.K.A. THE BEATLES; THE BEATLES - THE HOUSE THAT JACK BUILT; SOME FUN TONIGHT!; PAUL McCARTNEY - RECORDING SESSIONS 1969 - 2013. / FAB FOUR On DVD: A MUSICARES TRIBUTE TO PAUL McCARTNEY. -

2017 MAJOR EURO Music Festival CALENDAR Sziget Festival / MTI Via AP Balazs Mohai

2017 MAJOR EURO Music Festival CALENDAR Sziget Festival / MTI via AP Balazs Mohai Sziget Festival March 26-April 2 Horizon Festival Arinsal, Andorra Web www.horizonfestival.net Artists Floating Points, Motor City Drum Ensemble, Ben UFO, Oneman, Kink, Mala, AJ Tracey, Midland, Craig Charles, Romare, Mumdance, Yussef Kamaal, OM Unit, Riot Jazz, Icicle, Jasper James, Josey Rebelle, Dan Shake, Avalon Emerson, Rockwell, Channel One, Hybrid Minds, Jam Baxter, Technimatic, Cooly G, Courtesy, Eva Lazarus, Marc Pinol, DJ Fra, Guim Lebowski, Scott Garcia, OR:LA, EL-B, Moony, Wayward, Nick Nikolov, Jamie Rodigan, Bahia Haze, Emerald, Sammy B-Side, Etch, Visionobi, Kristy Harper, Joe Raygun, Itoa, Paul Roca, Sekev, Egres, Ghostchant, Boyson, Hampton, Jess Farley, G-Ha, Pixel82, Night Swimmers, Forbes, Charline, Scar Duggy, Mold Me With Joy, Eric Small, Christer Anderson, Carina Helen, Exswitch, Seamus, Bulu, Ikarus, Rodri Pan, Frnch, DB, Bigman Japan, Crawford, Dephex, 1Thirty, Denzel, Sticky Bandit, Kinno, Tenbagg, My Mate From College, Mr Miyagi, SLB Solden, Austria June 9-July 10 DJ Snare, Ambiont, DLR, Doc Scott, Bailey, Doree, Shifty, Dorian, Skore, March 27-April 2 Web www.electric-mountain-festival.com Jazz Fest Vienna Dossa & Locuzzed, Eksman, Emperor, Artists Nervo, Quintino, Michael Feiner, Full Metal Mountain EMX, Elize, Ernestor, Wastenoize, Etherwood, Askery, Rudy & Shany, AfroJack, Bassjackers, Vienna, Austria Hemagor, Austria F4TR4XX, Rapture,Fava, Fred V & Grafix, Ostblockschlampen, Rafitez Web www.jazzfest.wien Frederic Robinson, -

Jane Eyre Katherine Ryan

AUTUMN WINTER 2017 Jane Eyre Katherine Ryan Joseph SHED SEVEN Box office: 01482 300 306 www.hulltheatres.co.uk Working in partnership Access Performances The We are pleased to offer a number of assisted Interval performances throughout the season. is over and Jane Eyre the stage Saturday 23 September, 2pm is set for Captioned Performance something Kings of Hull Wednesday 4 October, 7.30pm incredible... Signed Performance Opera North Friday 27 October, 7.15pm It is with great pride that we re-open Hull Audio Description and Touch Tour New Theatre following its ambitious £16m major refurbishment and we are looking Joseph forward to our customers experiencing Wednesday 1 November, 7.30pm this incredible transformation. Signed Performance Officially opening on 16th September with a special performance presented by the Saturday 3 November, 2pm world-renowned Royal Ballet; following this Audio Description and Touch Tour is an exciting autumn programme of events including award winning musicals, critically Peter Pan acclaimed drama, dance, opera and a high Wednesday 13 December, 7pm flying pantomime adventure. Relaxed Performance Complementing this at the prestigious City Hall audiences can enjoy high quality Tuesday 19 December, 7pm entertainment at its best including, comedy, Signed Performance classical concerts, live music, festive celebrations and more. Hamlet Wednesday 14 February, 7.15pm With so much on offer, this is the perfect time to join our brand new Extras Captioned Performance membership scheme and take advantage Friday 16 February, 7.15pm of ticket discounts, priority booking and invitations to exclusive events. Signed Performance Read on to discover our wonderful Saturday 17 February, 1.45pm programme of events and we are delighted Audio Description and Touch Tour to welcome you all to our venues for what promises to be a great season. -

Stijdenincorporating Jail R Magazine � Britain's Biggest Weekly Student Newspaper April 26, 1996

26 APR 1!:":i'j They think it's all over HOW DID MIR TEAM WORE OVER THE EASIER VOW CUISSIFIED RESULTS SERVICE: TOTAL FOOTSAEL. PAGE 17 STIJDENIncorporating jail r magazine Britain's biggest weekly student newspaper April 26, 1996 THEY TREATED ME LIKE A TERRORIST' SAYS JAILED STUDENT Thrown in solitary for losing passport B MARTIN ARNOLD. CHIEF REPORTER A SPANISH field trip turned into a r nightmare for student Mark Vinton when RADIO DAYS ARE HERE AGAIN airport police refused him entry and threw him in solitary confinement. Heavy-handed officials bundled Mark into a cell because he could not produce his passport - it had been lost in the post. Yet hours before the trip Mark had received a special fax from Spanish immigration officials authorising his entry to the country. Airport police dismissed it and locked Mark away, while tutors pleaded in vain for his release, Mark was stopped as he arrived with a group of 60 other Leeds University students and four lecturers. -They thought I was a terrorist.," said Mark. tried to reason v.ith them but they juvi wouldn't listen." Astonished Spanish police detained the astonished student in solitary confinement for more than seven hours as they sought to deport him back to Britain. It was only after an intervention by the Home Office that he was filially released and allowed to rejoin the Leeds $roup. University staff who attempted to intervene through their travel agent had been told nobody would be allowed to speak to Mark as he ramd immediate di:potation. -

Frank Zappa's Legacy: Just Another Hoover? L’Héritage De Frank Zappa : Juste Un Autre « Hoover »? Ben Watson

Document generated on 09/26/2021 6:09 p.m. Circuit Musiques contemporaines Frank Zappa's Legacy: Just Another Hoover? L’héritage de Frank Zappa : juste un autre « Hoover »? Ben Watson Frank Zappa : 10 ans après Article abstract Volume 14, Number 3, 2004 In "Frank Zappa's Legacy: just another Hoover?", Ben Watson reveals that when Frank Zappa referred to his "oeuvre" towards the end of his life, he URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/902325ar pronounced the French word like "Hoover", the world's most famous brand of DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/902325ar vacuum cleaner. Watson's essay starts with the proposition that Zappa's oeuvre is indeed a Hoover, a critical manoeuvre appropriate for Zappa's Dadaist See table of contents disdain for cultural values. Establishment critics currently praise Zappa's "genius" as a composer, but this removes the critical sting of his records. In fact, what made Zappa special was his recognition that both commercial commodification and the heritage industry (concepts of "genius") repress Publisher(s) desire and suppress music. In a detour into literary and psychoanalytical Les Presses de l'Université de Montréal theory, Watson's zappological algebra reaches the equation: Stéphane Mallarmé + Wilhelm Reich = Frank Zappa. After an art-historical examination of the Hoover motif in Zappa's oeuvre, Zappa's heritage is assessed today: ISSN Project/Object, the Muffin Men, The Simpsons and the improvising trio of 1183-1693 (print) Eugene Chadbourne, Jimmy Carl Black and Pat Thomas are singled out for 1488-9692 (digital) praise. Explore this journal Cite this article Watson, B. -

Assembly Hall Theatre, Tunbridge Wells Box Office: 01892 530613 Spring 2020 Assemblyhalltheatre.Co.Uk

Assembly Hall Theatre, Tunbridge Wells Box Office: 01892 530613 Spring 2020 assemblyhalltheatre.co.uk Guide CLICK HERE CLICK HERE TO BOOK TO BOOK Royal Tunbridge Wells Symphony Orchestra present Time 3pm Cuffe & Taylor present Time 7.30pm Martin James Bartlett Running time 2 hours 30 mins What’s Love Got To Do With It? Running time 2 hours 10 mins approx. (inc. interval) approx. (inc. interval) Sunday 1 March A Tina Turner Tribute Tickets Friday 6 March Tickets Copland: Appalachian Spring Suite Full Price from £27 Full Price from £27.75 Ravel: Piano Concerto in G major Child (18yrs and under) £1 A brand new show celebrating the music of Tina Brahms: Symphony No 4 Student £1 Turner comes to Tunbridge Wells. Discounts Soloist: Martin James Bartlett Piano Brought to you by the award-winning producers behind A limited number of Go Card Discounts the hugely successful Whitney - Queen Of The Night, tickets are available for £10 Conductor: Roderick Dunk A limited number of Go Card What’s Love Got To Do With It? pays homage to one Our concerto this month is Maurice Ravel’s Piano tickets are available for £10 of the most iconic and much loved musical artists of Access Concerto in G major, a thrilling and lively work written the 20th Century. in the 1920s, full of jazz-inspired musical ideas set For specific access requests Access against a beautiful and tranquil Mozart-like slow In this brand-new touring theatre show, audiences can including wheelchair bookings movement. The ballet Appalachian Spring, with music For specific access requests expect a night of high energy, feel-good rock-and-roll or general access information by American composer Aaron Copland, is about early including wheelchair bookings featuring Tina’s greatest hits performed by the amazing please contact the theatre Box 19c American pioneers and quotes the famous Shaker or general access information vocal talent of Elesha Paul Moses (Whitney - Queen Office on 01892 530613 (Mon tune ‘Tis the Gift to be Simple’.