The Navy Everywhere (1919)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coastal Profile for Tanzania Mainland 2014 District Volume II Including Threats Prioritisation

Coastal Profile for Tanzania Mainland 2014 District Volume II Including Threats Prioritisation Investment Prioritisation for Resilient Livelihoods and Ecosystems in Coastal Zones of Tanzania List of Contents List of Contents ......................................................................................................................................... ii List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................. x List of Figures ......................................................................................................................................... xiii Acronyms ............................................................................................................................................... xiv Table of Units ....................................................................................................................................... xviii 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 19 Coastal Areas ...................................................................................................................................... 19 Vulnerable Areas under Pressure ..................................................................................................................... 19 Tanzania........................................................................................................................................................... -

Southwest Coast of Africa

PUB. 123 SAILING DIRECTIONS (ENROUTE) ★ SOUTHWEST COAST OF AFRICA ★ Prepared and published by the NATIONAL GEOSPATIAL-INTELLIGENCE AGENCY Springfield, Virginia © COPYRIGHT 2012 BY THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT NO COPYRIGHT CLAIMED UNDER TITLE 17 U.S.C. 2012 THIRTEENTH EDITION For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: http://bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2250 Mail Stop: SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-0001 II Preface 0.0 Pub. 123, Sailing Directions (Enroute) Southwest Coast of date of the publication shown above. Important information to Africa, Thirteenth Edition, 2012, is issued for use in conjunc- amend material in the publication is available as a Publication tion with Pub. 160, Sailing Directions (Planning Guide) South Data Update (PDU) from the NGA Maritime Domain web site. Atlantic Ocean and Indian Ocean. The companion volume is Pubs. 124. 0.0NGA Maritime Domain Website 0.0 Digital Nautical Chart 1 provides electronic chart coverage http://msi.nga.mil/NGAPortal/MSI.portal for the area covered by this publication. 0.0 0.0 This publication has been corrected to 18 August 2012, in- 0.0 Courses.—Courses are true, and are expressed in the same cluding Notice to Mariners No. 33 of 2012. manner as bearings. The directives “steer” and “make good” a course mean, without exception, to proceed from a point of or- Explanatory Remarks igin along a track having the identical meridianal angle as the designated course. Vessels following the directives must allow 0.0 Sailing Directions are published by the National Geospatial- for every influence tending to cause deviation from such track, Intelligence Agency (NGA), under the authority of Department and navigate so that the designated course is continuously be- of Defense Directive 5105.40, dated 12 December 1988, and ing made good. -

Raad Voor De Scheepvaart (1908) 1909-2010

Nummer Toegang: 2.16.58 Inventaris van het Archief van de Raad voor de Scheepvaart (1908) 1909-2010 Versie: 11-05-2021 Doc-Direkt Nationaal Archief, Den Haag (c) 2018 This finding aid is written in Dutch. 2.16.58 Raad voor de Scheepvaart 3 INHOUDSOPGAVE Beschrijving van het archief......................................................................................5 Aanwijzingen voor de gebruiker................................................................................................6 Openbaarheidsbeperkingen.......................................................................................................6 Beperkingen aan het gebruik......................................................................................................6 Materiële beperkingen................................................................................................................6 Aanvraaginstructie...................................................................................................................... 6 Citeerinstructie............................................................................................................................ 6 Archiefvorming...........................................................................................................................7 Geschiedenis van de archiefvormer............................................................................................7 Taakuitvoering (procedures)..................................................................................................7 -

A History of the Colonization of Africa by Alien Races

OufO 3 1924 074 488 234 All books are subject to recall after two weeks Olin/Kroch Library DATE DUE -mr -^ l99T 'li^^is Wtt&-F£SeiW SPRIHG 2004 PRINTED IN U.S.A. The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924074488234 In compliance with current copyright law, Cornell University Library produced this replacement volume on paper that meets the ANSI Standard Z39.48-1984 to replace the irreparably deteriorated original. 1994 (Kambtitrge i^istotical Series EDITED BY G. W. PROTHERO, LiTT.D. HONORARY FELLOW OF KING'S COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE, AND PROFESSOR OF HISTORY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH. THE COLONIZATION OF AFRICA. aonbon: C. J. CLAY AND SONS, CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS WAREHOUSE, Ave Maria Lane. ©lasBoiu: 263, ARGYLE STREET. Ecipjis: F. A. BROCKHAUS. jjefagorl:: THE MACMILLAN COMPANY. JSomlaj: E. SEYMOUR HALE. A HISTORY OF THE COLONIZATION OF AFRICA BY ALIEN RACES BY SIR HARRY H. JOHNSTON, K.C.B. (author of "BRITISH CENTRAL AFRICA," ETC.). WITH EIGHT MAPS BY THE AUTHOR AND J. G. BARTHOLOMEW. CAMBRIDGE: AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS. 1899 9 [All Rights reserved-^ GENERAL TREFACE. The aim of this series is to sketch tlie history of Alodern Europe, with that of its chief colonies and conquests, from about the e7id of the fifteenth century down to the present time. In one or two cases the story will connnence at an earlier date : in the case of the colonies it will usually begin later. -

STUDY GUIDE DA UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL Pressing Topics in the International Agenda

ABOUT THE JOURNAL UFRGS Model United Nations Journal is an academic vehicle, linked to UFRGSMUN, an sponsors Extension Project of the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. It aims to contribute to the academic production in the fields of Inter- national Relations and International Law, as well as related areas, through the study of STUDY GUIDE DA UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL pressing topics in the international agenda. The DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL journal publishes original articles in English and Portuguese, about issues related to peace and security, environment, world economy, inter- national law, regional integration and defense. The journal’s target audience are undergradu- ate and graduate students. All of the contribu- tions to the journal are subject of careful scien- tific revision by postgraduate students. The journal seeks to promote the engagement in the debate of such important topics. STUDY GUIDE SOBRE O PERIÓDICO support O periódico acadêmico do UFRGS Modelo das Nações Unidas é vinculado ao UFRGSMUN, um frgs Projeto de Extensão da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul que possui como objetivo 2016 contribuir para a produção acadêmica nas áreas PPGEEI - UFRGS Núcleo Brasileiro de Estratégia e Relações Internacionais Programa de Pós-Graduação em de Relações Internacionais e Direito Internacio- Estudos Estratégicos Internacionais nal, bem como em áreas afins, através do estudo de temas pertinentes da agenda inter- nacional. O periódico publica artigos originais em inglês e português sobre questões relacio- nadas com paz e segurança, meio ambiente, frgs Instituto Sul-Americano de Política e Estratégia 2016 economia mundial, direito internacional, defesa Empowering people, e integração regional. -

Introduction and List of Stations

INTRODUCTION AND LIST OF STATIONS BY Lt.-Col. R. B. SEYMOUR SEWELL, CJ.E., Sc.D., F R.S., LM.S.(ret) WITH FRONTISPIECE AND ONE CHART. CONTENTS. p a g e L i s t s o f C o m m i t t e e a n d S t a f f ............................................................................................................................. 1 B r i e f N a r r a t i v e o f V o y a g e ..........................................................................................................................................2 T h e S h i p a n d t h e S c i e n t i f i c E q u i p m e n t ..............................................................................................9 M e t h o d s o f P reservation , e t c ...................................................... ..............................................................................1 2 L i s t s o f S t a t i o n s ............................................................................................................................................................ 1 5 THE JOHN MURRAY EXPEDITION. C o m m i t t e e . Mr. J. C. Murray, President and Treasurer. Professor J. Stanley Gardiner, F.R.S., Secretary. Dr. E. J. Allen, D.Sc., F.R.S. Dr. W. T. Caiman, C.B., D.Sc., F.R.S. Vice-Admiral Sir Percy Douglas, K.C.B.. C.M.G., R.N. (ret.). Rear-Admiral J. A. Edgell, O.B.E., R.N., Hydrographer to the Admiralty. Dr. S. W. Kemp, Sc.D., F.R.S. Dr. C. Tate Regan, M.A., D.Sc., F.R.S. Professor G. I. Taylor, M.A., F.R.S. Captain J. P. R. Marriott, R.N. (ret.). Mr. -

Np 2 Africa Pilot Volume Ii

NP 2 RECORD OF AMENDMENTS The table below is to record Section IV Notice to Mariners amendments affecting this volume. Sub paragraph numbers in the margin of the body of the book are to assist the user with corrections to this volume from these amendments. Weekly Notices to Mariners (Section IV) 2005 2006 2007 2008 IMPORTANT − SEE RELATED ADMIRALTY PUBLICATIONS This is one of a series of publications produced by the United Kingdom Hydrographic Office which should be consulted by users of Admiralty Charts. The full list of such publications is as follows: Notices to Mariners (Annual, permanent, temporary and preliminary), Chart 5011 (Symbols and abbreviations), The Mariner’s Handbook (especially Chapters 1 and 2 for important information on the use of UKHO products, their accuracy and limitations), Sailing Directions (Pilots), List of Lights and Fog Signals, List of Radio Signals, Tide Tables and their digital equivalents. All charts and publications should be kept up to date with the latest amendments. NP 2 AFRICA PILOT VOLUME II Comprising the west coast of Africa from Bakasi Peninsula to Cape Agulhas; islands in the Bight of Biafra; Ascension Island; Saint Helena Island; Tristan da Cunha Group and Gough Island FOURTEENTH EDITION 2004 PUBLISHED BY THE UNITED KINGDOM HYDROGRAPHIC OFFICE E Crown Copyright 2004 To be obtained from Agents for the sale of Admiralty Charts and Publications Copyright for some of the material in this publication is owned by the authority named under the item and permission for its reproduction must be obtained from the owner. First published. 1868 Second edition. 1875 Third edition. -

" Pierre Gouin

I\ IDRC -118e " PIERRE GOUIN ARCHIV .1 37072 IDRC-118e EARTHQUAKE HISTORY of ETHIOPIA and the HORN OF AFRICA Pierre Gouin Director of the Geophysical Observatory University of Addis Ababa, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia From 1957 to 1978 This monograph is a companion volume to "Seismic Zoning in Ethiopia" published by the Geophysical Observa- tory, University of Addis Ababa. It gives the primary and secondary sources as well as the interpretation on which the statistical analyses of regional seismic and volcanic hazards were based. Throughout the text, mention ofpolitical boun- daries is intended only to orient the reader and has been resorted to only when other well-known reference points were unavailable. They in no way should be considered as reflecting exact international boundaries. In addition to this publication, IDRC sponsored part of the research between 1974 and 1978 in cooperation with the Geophysical Observatory of the University of Addis Ababa. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the International Development Research Centre. SrC , 31/- /./;- The International Development Research Centre is a public corporation created by the Parliament of Canada in 1970 to support research designed to adapt science and technology to the needs of developing countries. The Centre's activity is concentrated in five sectors: agriculture, food and nutrition sciences; health sciences; information sciences; social sciences; and communications. IDRC is financed solely by the Government of Canada; its policies, however, are set by an international Board of Governors. The Centre's headquarters are in Ottawa, Canada. Regional offices are located in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East. -

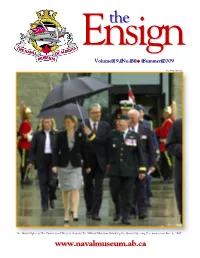

Ensign Summer 04 Pp 01-12

Ensignthe Volume19,No.3 ◆ Summer2009 The Military Museums Her Royal Highness The Countess of Wessex, departs The Military Museums following the Grand Opening Ceremonies on June 6, 2009. www.navalmuseum.ab.ca The Grand Opening The Chairman's Saturday, June 6th, 2009 Bridge By Tom Glover am pleased to report that the new Naval Museum of Alberta has been off to a fine start since we opened in October last year. Our attend- Iance initially was better than any of our previous records at the old HMCS Tecum- seh site. Since the Grand Opening by So- phie the Countess of Wessex on June 6, 2009, our attendance has been steadily in- creasing. Over the past several months we have been averaging well over 3,000 guests per month. This figure includes school groups, cadet organisations, naval, air force and regimental groups and mem- bers of the general public. All museum operations are now un- dergoing fine tuning. Governance issues are being addressed and new staff and volunteers are being trained in the varie- ty of activities in support of museum op- erations. Your board and executive committee continue to be active in all aspects of the transition, and are either monitoring the fine tuning that is in progress, or partici- pating in the development and introduc- tion of revised policies and procedures that are needed in the new multiple gal- lery museum environment. Preparations are underway for our big fall event featuring the Admirals' Medal presentation to our own Captain(N) Bill 'The Rabbiter' Wilson. On October 21, 2009—the 204th anniversa- ry of the Battle of Trafalgar—a presenta- Capt(N) Bill Wilson, Frank Saies-Jones, Harold Hutchinson, HRH the Countess of tion ceremony is planned for Bill, and the Wessex and VAdm J. -

Universidade Federal Da Bahia Status of Climate Change

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DA BAHIA INSTITUTO DE GEOCIÊNCIAS OCEANOGRAFIA ELISSAMA DE OLIVEIRA MENEZES STATUS OF CLIMATE CHANGE IN TROPICAL BAYS A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW Salvador 2018 12 ELISSAMA DE OLIVEIRA MENEZES STATUS OF CLIMATE CHANGE IN TROPICAL BAYS A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW Monografia apresentada ao Curso de Oceanografia, Instituto de Geociências, Universidade Federal da Bahia, como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Bacharel em Oceanografia. Orientador: Prof. JOSÉ MARIA LANDIM DOMINGUEZ Co-orientadora: CARLA ISOBEL ELLIFF Salvador 2018 13 TERMO DE APROVAÇÃO ELISSAMA DE OLIVEIRA MENEZES STATUS OF CLIMATE CHANGE IN TROPICAL BAYS: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW Monografia apresentada como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Bacharel em Oceanografia, Universidade Federal da Bahia, pela seguinte banca examinadora: __________________________________ ____________________________________________ Dr. José Maria Landim Dominguez – Orientador Universidade Federal da Bahia ____________________________________________ Dra. Junia Guimarães Universidade Federal da Bahia ____________________________________________ M.Sc. Yuri Costa Universidade Federal da Bahia Salvador, 23 de Fevereiro de 2018 14 “Mãe, o que é o oceano?” “Uma quantidade de água que banha os continentes” Sobre simplicidade com Jaci Paula Menezes 15 AGRADECIMENTOS Agradeço a Deus por estar presente, por ser presença e por colorir o meu mundo de amor. Agradeço ao Oceano por ser minha fonte de inspiração, minha melhor terapia e o melhor lugar do mundo. Agradeço a minha mãe, Jaci Paula, por ser meu porto seguro e fortaleza, a razão de tudo e a mulher mais incrível que conheço. Agradeço a meus irmãos, Jônatas e Hilquias, pela assistência e inspiração. A minha avó por ser raiz e deixar que me afague em seus braços. Agradeço a Rafael, meu companheiro, por todo suporte durante a minha graduação e por adoçar minha vida com sua presença. -

Universidad De Jaén El Estrecho De Gibraltar

UNIVERSIDAD DE JAÉN ESCUELA DE DOCTORADO DERECHO PÚBLICO Y COMÚN EUROPEO TESIS DOCTORAL • EL ESTRECHO DE GIBRALTAR: PROTECCIÓN INTERNACIONAL Y NACIONAL DE SU MEDIO AMBIENTE MARINO PRESENTADA POR: RABÍA MRABET TEMSAMANI DIRIGIDA POR: Prof. Dr. VICTOR LUIS GUTIERREZ CASTILLO JAÉN, FECHA ISBN EL ESTRECHO DE GIBRALTAR: PROTECCIÓN INTERNACIONAL Y NACIONAL DE SU MEDIO AMBIENTE MARINO Al gran ausente presente en mi vida. A la memoria de mi padre que dejó este mundo de repente el 8 de junio del 2011. Agradecimiento Agradecer, es una palabra muy corta ante los reconocimientos que puede expresar cualquier doctorando/a para aquéllas personas que fueron su luz en la oscuridad, su esperanza en la desesperación y su carburante en el impotencia. Mis agradecimientos familiares son para mi madre, mi hermana y hermano; Ouafaa y Sidi Mohammed por lo que hicieron, hacen y están haciendo Mis agradecimientos académicos son para: Prof. Dr. Juan Luis SUAREZ DE VIVERO por su disponibilidad, generosidad y amabilidad desveladas desde el primer encuentro; Dr. Tarik ATMANE por su simpatía, por todo el material que me ha pasado y por su libro que me ha regalado. Mis agradecimientos son para mis amigos/as, que siempre estaban conmigo a lo largo de mis aventuras académicas. Sobre todo para aquellas personas, que ni el paso del tiempo ni la distancia han afectado nuestra amistad que se ha visto cada vez más fortalecida. Mis últimos agradecimientos deben ser los que preceden la presentación de este trabajo, por ser a la persona que confió en mí y ha estado donde tuvo que estar en su tiempo, por todo su apoyo, ayuda, consejos y respecto. -

GIPE-002290-Contents.Pdf

, )hananjayarao Gadgil Library j IIIIIIII~~ I~~ I~IIIIIIII~IIIIIIIII : ~-PUNE-002290 (!ambtibge 11listntical Seties EDITED BY G. W. PROTHERO, Lrrr.D. BONOL\ll.Y FBLLOW OF lUNG's COLLBGE, CAJOIIU~ AND PJLOF&SSOJL OF BISTOJLY iN TBX UNIVEllSlTY OF liIS1NB~ THE COLONIZATION OF AFRICA Uonbon: C. J. CLAY AND SONS, C~MBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS WAREHOUSE, AVE MARIA LANE. Slugalll: 26], ARGYLE STREET. ~: F. A. BROCKHAUS. -= Jl!arIt: THE MACMILLAN COMPANY. lSOIIIhBl!: E. SEYMOUR HALE. A HISTORY OF THE COLONIZATION OF AFRICA BY ALIEN RACES BY SIR HARRY H. JOHNSTON, K.C.B. (AUTHOIt OF II BItITISH CENTItAL AFRICA," ETC.). WITH EIGHT MAPS BY THE AUTHOR AND J. G. BARTHOLOMEW. CAMBRIDGE: AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS. 1899 [All Rightl ,.eltl"lled.] GENERAL PREFACE. The aim of this series is to skdclt tlte Itistory of Motknt Europe, fllitlt tltal Of its dzUf (O/onies and «J1IIjuests, frt»" alJout tlte nul of tlte jiftemllt cmtury tluwn to lite prese1fl lime. In one or two cases tlte story wiU com_a at an earlUr date: ;" lite case of lite (Olonies it wiD usually !Jegin later. The Itistories of lite i/iffermt (lJUtflries wiD !Je tlest:ri!Jul, as a gmeral rule, separately, for it is lJdiewIJ tltal, acept ;" ejJot:lts /ike lltal of tIze Frmelt RivolutUm and Napolum I, tlte cqn1ltt:lio1f of evmIs wiD thus !Je !Jetter untkrstood and the-amli_ity of Itistori&a/ tkodop mmI more dearly displayeli. The series is intenduJ for lhe use Of aU persons anxWus to untkrsland lite ;,alure of existing po/itiad lIJnditilms. "The roots of lite presml lie tieep in tlte past," and lite real sig1fifoa1lt:e of contemporary events cannot !Je graspetl -utUess tlte historical fIluses whidz hil'iJe lui to tltem are hunt",.