The Law and Strategy of the Gold Train Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Senate the Senate Met at 9:45 A.M

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 108 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 150 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 14, 2004 No. 109 Senate The Senate met at 9:45 a.m. and was U.S. SENATE, ple to come in late. In order to finish called to order by the Honorable LIN- PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE, the bill, especially as we want to pay COLN D. CHAFEE, a Senator from the Washington, DC, September 14, 2004. appropriate respect to the Jewish holi- State of Rhode Island. To the Senate: day tomorrow, I plead with our col- Under the provisions of rule I, paragraph 3, of the Standing Rules of the Senate, I hereby leagues that they come as soon as they PRAYER appoint the Honorable LINCOLN D. CHAFEE, a are notified there will be a vote. We The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- Senator from the State of Rhode Island, to give everyone a heads-up when there fered the following prayer: perform the duties of the Chair. will be a vote. Come and vote and leave Let us pray. TED STEVENS, and efficiently use that time. O Lord, our rock, hear our praise President pro tempore. Mr. REID. Will the Senator yield? today, for Your faithfulness endures to Mr. CHAFEE thereupon assumed the Mr. FRIST. I am happy to yield for a all generations. You hear our prayers. chair as Acting President pro tempore. question. Mr. REID. Mr. President, I am so Surround us with Your mercy. -

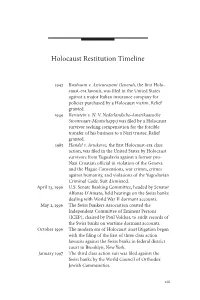

Holocaust Restitution Timeline

Holocaust Restitution Timeline 1942 Buxbaum v. Assicurazioni Generali, the first Holo- caust-era lawsuit, was filed in the United States against a major Italian insurance company for policies purchased by a Holocaust victim. Relief granted. 1949 Bernstein v. N. V. Nederlandsche-Amerikaansche Stoomvaart-Maatschappij was filed by a Holocaust survivor seeking compensation for the forcible transfer of his business to a Nazi trustee. Relief granted. 1985 Handel v. Artukovic, the first Holocaust-era class action, was filed in the United States by Holocaust survivors from Yugoslavia against a former pro- Nazi Croatian official in violation of the Geneva and the Hague Conventions, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and violations of the Yugoslavian Criminal Code. Suit dismissed. April 23, 1996 U.S. Senate Banking Committee, headed by Senator Alfonse D’Amato, held hearings on the Swiss banks dealing with World War II dormant accounts. May 2, 1996 The Swiss Bankers Association created the Independent Committee of Eminent Persons (ICEP), chaired by Paul Volcker, to audit records of the Swiss banks on wartime dormant accounts. October 1996 The modern era of Holocaust asset litigation began with the filing of the first of three class action lawsuits against the Swiss banks in federal district court in Brooklyn, New York. January 1997 The third class action suit was filed against the Swiss banks by the World Council of Orthodox Jewish Communities. xiii xiv Holocaust Restitution Timeline January 8, 1997 Christoph Meili discovered the Union Bank of Switzerland attempting to shred pre–World War II financial documents. March 25, 1997 French Prime Minister Alain Juppe created the Prime Minister’s Office Study Mission into the Looting of Jewish Assets in France (“Mattéoli Commission”) to study various forms of theft of Jewish property during World War II and the postwar efforts to remedy such theft. -

2006–07 Annual Report (PDF)

What canI do? Can hatred be stopped? Will future generations remember the Holocaust? After the Holocaust, why can’t the world stop genocide? What canI do? Am I a bystander? A living memorial to the Holocaust, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum inspires leaders and citizens to confront hatred, prevent genocide, promote human dignity and strengthen democracy. Federal support guarantees the Museum’s permanent place on the National Mall, but its educational programs and global outreach are made possible by the generosity of donors nationwide through annual and legacy giving. 2006–07 | ANNUAL REPORT UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM ushmm.org 100 Raoul Wallenberg Place, SW Washington, DC 20024-2126 ushmm.org What must be done? What is the Museum’s role in the 21st century? What have we learned from history? From Our Leadership he crimes of the Holocaust were once described as “so calculated, so malignant, and Tso devastating that civilization cannot bear their being ignored because it cannot survive their being repeated.” How do we move from memory to action? When Justice Robert Jackson uttered these words at Nuremberg, could he have possibly imagined that six decades later his assertion would be a matter of doubt? These words marked what seemed to be a pivotal moment, a watershed in which all that followed would remain in the long shadow of the crime. There was a commitment to not ignore, to not repeat. Yet today, we must ask: Have we arrived at another pivotal moment in which the nature of the crime feels quite relevant, yet the commitment to prevent another human tragedy quite hollow? What must be done? What can we do as individuals? As institutions? | FROM OUR LEADERSHIP 1 For us the key question is: What is the role of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum? 2 | CONFRONTING ANTISEMITISM AND DENIAL 16 | PREVENTING GENOCIDE The Museum cannot eliminate evil and hatred. -

Holocaust Restitution, the United States Government, and American Industry Michael J

Brooklyn Journal of International Law Volume 28 | Issue 3 Article 2 2002 Trading With The neE my: Holocaust Restitution, the United States Government, and American Industry Michael J. Bazyler Amber L. Fitzgerald Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil Recommended Citation Michael J. Bazyler & Amber L. Fitzgerald, Trading With The Enemy: Holocaust Restitution, the United States Government, and American Industry, 28 Brook. J. Int'l L. (2003). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil/vol28/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. File: BAZYLER Base Macro Final_2.doc Created on: 6/24/2003 12:17 PM Last Printed: 1/13/2004 2:22 PM TRADING WITH THE ENEMY: HOLOCAUST RESTITUTION, THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT, AND AMERICAN INDUSTRY Michael J. Bazyler∗ & Amber L. Fitzgerald∗∗ I. INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………685 II. THE ROLE OF THE UNITED STATES IN RESTITUTION EFFORTS ABROAD…………………………………………………………...686 A. Switzerland………...……………………………………….689 B. Germany..…………………………………………………...690 C. France......…………………………………………………...697 D. Austria………………..……………………………………..699 E. Israel……………………………...………………………….700 F. Insurance Claims…………………………………………..702 G. Art……………………………………………………………709 H. Role of Historical Commissions..………………………..712 1. Switzerland…………………………………………….712 a. Volcker Report……………………………………713 b. Bergier Final Report…………………………….715 2. Germany………………………………………………..719 3. Austria………………………………………………….720 4. France…………………………………………………..721 5. Other Countries……………………………………….723 ∗ Professor of Law, Whittier Law School, Costa Mesa, California; Fellow, Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies, U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum (“USHMM”), Washington, D.C.; Research Fellow, Holocaust Educational Trust, London, England; J.D., University of Southern California, 1978; A.B., University of California, Los Angeles, 1974. -

U.S. Reply Memorandum in Rosner V. United States

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA Case No. 01-1859-CIV SEITZ IRVING ROSNER, et al., ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) ) UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ) ) Defendant. ) ) DEFENDANT’S REPLY MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF ITS MOTION TO DISMISS PLAINTIFFS’ FIRST AMENDED COMPLAINT TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 ISSUES OF FACT ......................................................................................................................... 2 I. Facts Necessary to Determination of Subject Matter Jurisdiction ..................................... 2 A. Whether Property Belonging to Plaintiffs Came into the United States’ Possession (For Standing Determination) ...................................... 2 B. Whether Any Conduct by the United States Led Plaintiffs to Miss the Applicable Filing Deadline (For Statute of Limitations) .................... 3 C. When Plaintiffs Reasonably Could Have Exercised Due Diligence to Learn about the Gold Train (For Statute of Limitations) .................. 5 II. Additional Facts Relevant to Background and Merits of Plaintiffs’ Claims ..................... 6 A. Whether the Gold Train Property That Came into U.S. Possession Was Identifiable as to Individual Ownership ......................................................... 6 B. Whether Gold Train Property that Came into U.S. Possession was Identifiable as to National Origin .......................................................................... -

Hungary (As of 8 March 2017)

OVERVIEW OF IMMOVABLE PROPERTY RESTITUTION/COMPENSATION REGIME – HUNGARY (AS OF 8 MARCH 2017) CONTENTS A. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY B. POST-WAR ARMISTICES, TREATIES AND AGREEMENTS DEALING WITH RESTITUTION OF IMMOVABLE PROPERTY C. PRIVATE PROPERTY RESTITUTION D. COMMUNAL PROPERTY RESTITUTION E. HEIRLESS PROPERTY RESTITUTION F. BIBLIOGRAPHY A. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Hungary was an ally of Germany for most the war. By the terms of the 1947 Treaty of Peace with Hungary, Hungary committed to returning or providing compensation for private, communal and heirless property confiscated from Jews and other victims during the war. Little was done to act on these commitments during the Communist era. Instead, widespread nationalization resulted in a second wave of confiscation. Private Property. Claims by some foreign citizens relating to war damage and nationalization were settled before the fall of the Soviet Union through bilateral agreements with at least 16 foreign governments. With the exception of those Hungarian citizens who were able to rely on restitution measures enacted in the immediate post-war period before Hungary fell under Soviet influence, the remaining Hungarian citizens had to wait until 1991 and 1992 when domestic legislation was enacted to settle their property claims (Act XXV of 1991 and Act XXIV of 1992). These two laws were broad in scope but narrow in their remedy. They covered both lawfully and unlawfully taken property both during World War II and the Communist period. The laws provided limited compensation (not in rem restitution). In 1993, the Constitutional Court confirmed that the partial compensation scheme offered was in compliance with the Treaty of Peace with Hungary requirement that compensation be “fair”, and determined that full compensation for members of the Jewish community would constitute unjustified positive discrimination. -

Declaration of Jonathan G. Petropoulos

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ------------------------------------------------------X MARTIN GROSZ and LILIAN GROSZ : : Case No.: 09 Civ. 3706 (CM)(THK) Plaintiffs, : : against : : ECF CASE THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, : : Defendant, : : DECLARATION OF PORTRAIT OF THE POET MAX : JONATHAN G. PETROPOULOS HERRMANN-NEISSE With Cognac-Glass, : SELF-PORTRAIT WITH MODEL and : REPUBLICAN AUTOMATONS, : Three Paintings by George Grosz : : Defendants in rem. : : -----------------------------------------------------X JONATHAN G. PETROPOULOS deposes and certifies, as follows: 1. I am over the age of twenty-one and reside at 526 West 12th Street, Claremont, California, 91711. I have been retained by the attorneys for the heirs of George Grosz to provide this Declaration in relation to factual issues arising from a motion by the defendant, The Museum of Modern Art (“The MoMA”), to dismiss the First Amended Complaint (“FAC”). 2. Specifically, I have been requested to review two questions: (1) whether the allegations that three paintings by George Grosz, Portrait of the Poet Max-Herrmann- Neisse (with Cognac Glass), Self-Portrait with Model and Republican Automatons (together “the Paintings”), were lost or stolen are grounded in historical fact; and (2) whether the report of Nicholas deB. Katzenbach (“the Katzenbach Report”) submitted in support of the motion to dismiss is consistent with the historical record and provenance documentation available to art historians and scholars. As set forth below, a review of available documentation and scholarly resources shows: (1) that the allegations of the FAC appear to be supported by documentary evidence and otherwise well-grounded in historical fact and (2) that the statements contained in the Katzenbach Report are inconsistent with the historical record. -

War Crimes Records Pp.77-83 National Archives Collection of World War II War Crimes Records (RG 238)

1 First Supplement to the Appendix U.S. and Allied Efforts To Recover and Restore Gold and Other Assets Stolen or Hidden by Germany During World War II Finding Aid to Records at the National Archives at College Park Prepared by Dr. Greg Bradsher National Archives and Records Administration College Park, Maryland October 1997 2 Table of Contents pp.2-3 Table of Contents p.4 Preface Military Records pp.5-13 Records of the Office of Strategic Services (RG 226) pp.13-15 Records of the Office of the Secretary of War (RG 107) pp.15-22 Records of the War Department General and Special Staffs (RG 165) pp.22-74 Records of the United States Occupation Headquarters, World War II (RG 260) pp.22-72 Records of the Office of the Military Governor, United States OMGUS pp.72-74 Records of the U.S. Allied Commission for Austria (USACA) Section of Headquarters, U.S. Forces in Austria Captured Records pp.75-77 National Archives Collection of Foreign Seized Records (RG 242) War Crimes Records pp.77-83 National Archives Collection of World War II War Crimes Records (RG 238) Civilian Agency Records pp.84-88 General Records of the Department of State (RG 59) pp.84-86 Central File Records pp.86-88 Decentralized Office of “Lot Files” pp.88-179 Records of the Foreign Service Posts of the Department of State (RG 84) pp.88-89 Argentina pp.89-93 Austria pp.94-95 France pp.95-106 Germany pp.106-111 Great Britain pp.111-114 Hungary pp.114-117 Italy pp.117-124 Portugal pp.125-129 Spain pp.129-135 Sweden pp.135-178 Switzerland 3 pp.178-179 Turkey pp.179-223 Records of the American Commission for the Protectection and Salvage of Artistic and Historic Monumnts in War Areas (RG 239) pp.223-243 Records of the Foreign Economic Administration (RG 169) pp.243-244 Records of the High Commissioner for Germany (RG 466) pp.244-246 Records of the U.S. -

In the United States District Court for the District of Columbia

Case 1:10-cv-01770-BAH Document 24 Filed 05/06/11 Page 1 of 60 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ROSALIE SIMON, et al., * Individually, for themselves and for all * others similarly situated, * * Plaintiffs, * * v. * Case No. 1:10-cv-01770-BAH * THE REPUBLIC OF HUNGARY, et al., * * Defendants. * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * PLAINTIFFS’ MEMORANDUM OF LAW IN OPPOSITION TO MOTION OF DEFENDANTS THE REPUBLIC OF HUNGARY AND MAGYAR ÁLLAMVASUTAK ZRT. TO DISMISS THE FIRST AMENDED COMPLAINT Charles S. Fax, D.C. Bar No. 198002 L. Marc Zell, admitted pro hac vice Liesel J. Schopler, D.C. Bar No. 984298 Zell & Co. Rifkin, Livingston, Levitan & Silver, LLC 21 Herzog Street 7979 Old Georgetown Road, Suite 400 Jerusalem 92387 Israel Bethesda, Maryland 20814 Telephone: 011-972-2-633-6300 Telephone: (301) 951-0150 Telecopier: 011-972-2-672-1767 Telecopier: (301) 951-0172 [email protected] [email protected]; [email protected] David H. Weinstein, admitted pro hac vice Paul G. Gaston Weinstein Kitchenoff & Asher LLC Law Offices of Paul G. Gaston 1845 Walnut Street, Suite 1100 1776 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W, Suite 806 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19103 Washington, D.C. 20036 Telephone: (215) 545-7200 Telephone: (202) 296-5856 Telecopier: (215) 545-6535 Telecopier: (202) 296-4154 [email protected] [email protected] Dated: May 6, 2011 Attorneys for Plaintiffs Case 1:10-cv-01770-BAH Document 24 Filed 05/06/11 Page 2 of 60 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES . iii I. INTRODUCTION: THE TRUE NATURE OF THE HUNGARIAN HOLOCAUST 2 II. STATEMENT OF FACTS . -

Property Restitution in Central and Eastern Europe: the State of Affairs for American Claimants

PROPERTY RESTITUTION IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE: THE STATE OF AFFAIRS FOR AMERICAN CLAIMANTS HEARING BEFORE THE COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JULY 16, 2002 Printed for the use of the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe [CSCE 10727] Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.csce.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2003 84901.PDF For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: (202) 5121800 Fax: (202) 5122250 Mail Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 204020001 COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS HOUSE SENATE CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado Co-Chairman Chairman FRANK R. WOLF, Virginia KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas JOSEPH R. PITTS, Pennsylvania SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas ZACH WAMP, Tennessee GORDON H. SMITH, Oregon ROBERT B. ADERHOLT, Alabama GEORGE V. VOINOVICH, Ohio STENY H. HOYER, Maryland CHRISTOPHER J. DODD, Connecticut BENJAMIN L. CARDIN, Maryland BOB GRAHAM, Florida LOUISE MCINTOSH SLAUGHTER, New York RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin ALCEE L. HASTINGS, Florida HILLARY RODHAM CLINTON, New York EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS LORNE W. CRANER, Department of State JACK DYER CROUCH II, Department of Defense WILLIAM HENRY LASH III, Department of Commerce (ii) PROPERTY RESTITUTION IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE: THE STATE OF AFFAIRS FOR AMERICAN CLAIMANTS TUESDAY, JULY 16, 2002 COMMISSIONERS PAGE Hon. Christopher H. Smith, Co-Chairman ..................................................... 1 Hon. Joseph R. Pitts, Commissioner ............................................................... 3 Hon. Benjamin L. Cardin, Commissioner ...................................................... 3 Hon. Joseph Crowley, Member of Congress .................................................... 5 Hon. Hillary Rodham Clinton, Commissioner ............................................. 11 WITNESSES Randolph M. -

USHMM Finding

http://collections.ushmm.org Contact [email protected] for further information about this collection Documents Related to the History of the So‐Called Hungarian Jewish Gold Train, 1944‐1978 RG‐39.014M United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Archive 100 Raoul Wallenberg Place SW Washington, DC 20024‐2126 Tel. (202) 479‐9717 Email: [email protected] Descriptive Summary Title: Documents Related to the History of the So‐Called Hungarian Jewish Gold Train Dates: 1944-1978 RG Number: RG-39.014M Accession Number: 2007.242 Extent: 2 microfilm reels (16 mm) Repository: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Archive, 100 Raoul Wallenberg Place SW, Washington, DC 20024‐2126 Languages: Hungarian Administrative Information Access: No restrictions on access. Reproduction and Use: According to the terms of the United States‐Hungary Agreement, personal data of an individual mentioned in the records must not be published sooner than 30 years following the death of the person concerned, or if the year of death is unknown, for 90 years following the birth of the person concerned, or if both dates are unknown, for 60 years following the date of issue of the archival material concerned. "Personal data" is defined as any data that can be related to a certain natural person ("person concerned"), and any conclusion that can be drawn from such data about the person concerned. The full text of the Agreement is available at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Archives reference desk. Preferred Citation: RG‐39.014M, Documents Related to the History of the So‐Called Hungarian Jewish Gold Train, 1944-1978. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Archives, Washington, DC. -

Hearing the Schneerson Collection and Historical Justice.PDF

THE SCHNEERSON COLLECTION AND HISTORICAL JUSTICE HEARING BEFORE THE COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION APRIL 6, 2005 Printed for the use of the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe [CSCE 109–1–4] ( Available via http://www.csce.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 29–715 PDF WASHINGTON : 2006 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS HOUSE SENATE CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey, SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas, Co-Chairman Chairman FRANK R. WOLF, Virginia GORDON SMITH, Oregon JOSEPH R. PITTS, Pennsylvania SAXBY CHAMBLISS, Georgia ROBERT B. ADERHOLT, Alabama CHRISTOPHER J. DODD, Connecticut MIKE PENCE, Indiana RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin BENJAMIN L. CARDIN, Maryland HILLARY RODHAM CLINTON, New York LOUISE McINTOSH SLAUGHTER, VACANT New York VACANT ALCEE L. HASTINGS, Florida VACANT MIKE McINTYRE, North Carolina EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS VACANT, Department of State VACANT, Department of Defense WILLIAM H. LASH III, Department of Commerce (II) THE SCHNEERSON COLLECTION AND HISTORICAL JUSTICE APRIL 6, 2005 COMMISSIONERS Page Hon. Sam Brownback, Chairman, Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe ..................................................... 1 Hon. Christopher H. Smith, Co-Chairman, Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe ...................................... 3 Hon. Benjamin L. Cardin, Ranking Member, Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe ................................. 4 Hon. Alcee L. Hastings, Commissioner, Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe ...................................... 4 OTHER MEMBERS OF CONGRESS Hon.