Declaration of Jonathan G. Petropoulos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wiedergutmachung‹ Für Deutsche Museen? Die Beschlagnahmen ›Entarteter‹ Kunst in Den Bayerischen Staatsgemäldesammlungen 1937/38 Und Deren Entschädigung

Originalveröffentlichung in: Jahresbericht / Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen 2016, S. 136-152 ›Wiedergutmachung‹ für deutsche Museen? Die Beschlagnahmen ›entarteter‹ Kunst in den Bayerischen Staatsgemäldesammlungen 1937/38 und deren Entschädigung Johanna Poltermann »Keines dieser Bilder würde ich gekauft haben, auch wenn Kompensationen analysiert wird. Basis der vorliegenden sie noch so billig zu haben gewesen wären.«1 Mit diesen Untersuchung sind Akten in den Bayerischen Staatsgemälde- vernichtenden Worten charakterisierte der Frankfurter sammlungen, dem Bayerischen Hauptstaatsarchiv, dem Städel-Direktor Alfred Wolters vier Gemälde des 19. Jahr- Bundesarchiv Berlin sowie dem Zentralarchiv der Staatlichen hunderts, die als Sendung des Reichsministeriums für Wis- Museen zu Berlin. Um die geleistete Entschädigung in Re- senschaft, Erziehung und Volksbildung im Frühjahr 1942 lation zu den Verlusten setzen zu können, wird zunächst ein den ›Ersatz‹ für die beschlagnahmten Werke ›entarteter‹ Blick auf die Geschichte der Münchner Sammlung sowie die Kunst darstellten. Die Überweisung älterer Kunstwerke kulturpolitischen Verhältnisse vor und nach 1937 geworfen. an von der Beschlagnahme betroffene Museen war kein Einzelfall.2 Insgesamt 11 Museen erhielten 1942 sowohl diese Form der materiellen Entschädigung3 als auch zu- Die nationalsozialistische Kunst- und sätzlich eine finanzielle Zuweisung.4 Ein kurzer Vergleich Kulturpolitik und ihr Einfluss auf die Bayerischen der Zahlen genügt, um das Missverhältnis von Beschlagnah- Staatsgemäldesammlungen -

Hans Ulrich Obrist a Brief History of Curating

Hans Ulrich Obrist A Brief History of Curating JRP | RINGIER & LES PRESSES DU REEL 2 To the memory of Anne d’Harnoncourt, Walter Hopps, Pontus Hultén, Jean Leering, Franz Meyer, and Harald Szeemann 3 Christophe Cherix When Hans Ulrich Obrist asked the former director of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Anne d’Harnoncourt, what advice she would give to a young curator entering the world of today’s more popular but less experimental museums, in her response she recalled with admiration Gilbert & George’s famous ode to art: “I think my advice would probably not change very much; it is to look and look and look, and then to look again, because nothing replaces looking … I am not being in Duchamp’s words ‘only retinal,’ I don’t mean that. I mean to be with art—I always thought that was a wonderful phrase of Gilbert & George’s, ‘to be with art is all we ask.’” How can one be fully with art? In other words, can art be experienced directly in a society that has produced so much discourse and built so many structures to guide the spectator? Gilbert & George’s answer is to consider art as a deity: “Oh Art where did you come from, who mothered such a strange being. For what kind of people are you: are you for the feeble-of-mind, are you for the poor-at-heart, art for those with no soul. Are you a branch of nature’s fantastic network or are you an invention of some ambitious man? Do you come from a long line of arts? For every artist is born in the usual way and we have never seen a young artist. -

Jahresbericht 2016 2016 Bayerische Jahresbericht Staatsgemäldesammlungen Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen

BAYERISCHE STAATSGEMÄLDESAMMLUNGEN JAHRESBERICHT 2016 2016 BAYERISCHE STAATSGEMÄLDESAMMLUNGEN JAHRESBERICHT BAYERISCHE STAATSGEMÄLDESAMMLUNGEN JAHRESBERICHT Inhalt 6 Perspektiven und Projekte: Die Bayerischen Staatsgemäldesammlungen im Jahre 2016 104 06 Fördervereine 105 Pinakotheks-Verein 20 01 Ausstellungen, Projekte, Ereignisse 106 PIN. Freunde der Pinakothek der Moderne / Stiftung Pinakothek der Moderne 21 Ausstellungen 2016 107 International Patrons of the Pinakothek e. V. und American Patrons of the Pinakothek Trust 26 Die Schenkung der Art Mentor Foundation Lucerne an die Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlung und die Staatliche Graphische Sammlung München 110 07 Stiftungen 38 Schenkung der Max Beckmann-Nachlässe an das Max Beckmann Archiv 111 Stiftung Ann und Jürgen Wilde 41 Sammlung Schack: Wiedereröffnung des zweiten Obergeschosses 112 Fritz-Winter-Stiftung 42 Wiedereröffnung der Staatsgalerie in der Residenz Würzburg 113 Max Beckmann Archiv und Max Beckmann Gesellschaft 45 König Willem-Alexander und Königin Máxima der Niederlande eröffnen ›Holländer-Saal‹ 114 Theo Wormland-Stiftung 46 ›Renaissance & Reformation‹ in Los Angeles. Eine internationale Ausstellungskooperation 115 Olaf Gulbransson Gesellschaft e. V. Tegernsee 48 Bestandskatalog der Florentiner Malerei 49 Das ›Museum Experts Exchange Program‹ (MEEP). Ein chinesisch-deutsches Kooperationsprojekt 2014–2016 118 08 Nachruf 50 Untersuchungen und Bestandsaufnahme von Werken aus der Staatsgalerie Neuburg an der Donau 119 Johann Georg Prinz von Hohenzollern 54 Leihverkehr 121 09 -

1 1 December 2009 DRAFT Jonathan Petropoulos Bridges from the Reich: the Importance of Émigré Art Dealers As Reflecte

Working Paper--Draft 1 December 2009 DRAFT Jonathan Petropoulos Bridges from the Reich: The Importance of Émigré Art Dealers as Reflected in the Case Studies Of Curt Valentin and Otto Kallir-Nirenstein Please permit me to begin with some reflections on my own work on art plunderers in the Third Reich. Back in 1995, I wrote an article about Kajetan Mühlmann titled, “The Importance of the Second Rank.” 1 In this article, I argued that while earlier scholars had completed the pioneering work on the major Nazi leaders, it was now the particular task of our generation to examine the careers of the figures who implemented the regime’s criminal policies. I detailed how in the realm of art plundering, many of the Handlanger had evaded meaningful justice, and how Datenschutz and archival laws in Europe and the United States had prevented historians from reaching a true understanding of these second-rank figures: their roles in the looting bureaucracy, their precise operational strategies, and perhaps most interestingly, their complex motivations. While we have made significant progress with this project in the past decade (and the Austrians, in particular deserve great credit for the research and restitution work accomplished since the 1998 Austrian Restitution Law), there is still much that we do not know. Many American museums still keep their curatorial files closed—despite protestations from researchers (myself included)—and there are records in European archives that are still not accessible.2 In light of the recent international conference on Holocaust-era cultural property in Prague and the resulting Terezin Declaration, as well as the Obama Administration’s appointment of Stuart Eizenstat as the point person regarding these issues, I am cautiously optimistic. -

Museums' Initiation of Declaratory Judgment Actions and Assertion of Statutes of Limitations in Response to Nazi-Era Art Restitution Claims - a Defense

DePaul Journal of Art, Technology & Intellectual Property Law Volume 23 Issue 2 Spring 2013 Article 2 Museums' Initiation of Declaratory Judgment Actions and Assertion of Statutes of Limitations in Response to Nazi-Era Art Restitution Claims - A Defense Simon J. Frankel Ethan Forrest Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jatip Recommended Citation Simon J. Frankel & Ethan Forrest, Museums' Initiation of Declaratory Judgment Actions and Assertion of Statutes of Limitations in Response to Nazi-Era Art Restitution Claims - A Defense, 23 DePaul J. Art, Tech. & Intell. Prop. L. 279 (2013) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jatip/vol23/iss2/2 This Lead Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Journal of Art, Technology & Intellectual Property Law by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Frankel and Forrest: Museums' Initiation of Declaratory Judgment Actions and Assertion MUSEUMS' INITIATION OF DECLARATORY JUDGMENT ACTIONS AND ASSERTION OF STATUTES OF LIMITATIONS IN RESPONSE TO NAZI-ERA ART RESTITUTION CLAIMS-A DEFENSE Simon J. Frankel and Ethan Forrest* ABSTRACT Since the reunification of Germany brought greater access to information about the history and location of artworks that changed hands during the Nazi era, numerous restitution claims have been asserted to works held by U.S. museums. In a few instances, U.S. museums faced with such claims have initiated declaratoryjudgment actions seeking to quiet title to the works and have also invoked statutes of limitations or laches to bar the claims. -

Copies of Artworks the Case of Paintings and Prints* Françoise

Copies of Artworks The Case of Paintings and Prints* Françoise Benhamou Université de Rouen and MATISSE, Université de Paris I and Victor Ginsburgh ECARES, Université Libre de Bruxelles and CORE, Université catholique de Louvain January 2005 Abstract * The paper freely draws on our previous (2001) paper. We are grateful to M. Aarts, Me Cornette de St. Cyr, M. Cornu, D. Delamarre, M. Fouado-Otsuka, Me Lelorier, T. Lenain, M. Melot, O. Meslay, D. Schulmann, B. Steyaert, G. Touzenis, H. Verschuur and S. Weyers for very useful conversations and comments. Neil De Marchi's very careful comments on a preliminary version of the paper at the Princeton Conference led to several changes. We also thank Alvin Huisman (2001) who collected data on auctions 1976-1999. The second author acknowledges financial support from Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique. 1 "We use copies to certify originals, originals to certify copies, then we stand bewildered." Hillel Schwartz Research on copies is essentially focused on industrial activities (books, records, fashion, protection of patents) and on the incentives or disincentives to creativity resulting from copyright.1 But copies are also linked to questions concerned with value, the allocation of property rights, and regulation, three central questions in economics. In his essay on imitation in the arts, Adam Smith (1795) considers that the exact copy of an artwork always deserves less merit than the original.2 But the hierarchy between copies and originals has changed over time. So has the perception of copies by lawyers, philosophers, art historians and curators. The observation of these changes can be used to analyze art tastes and practices. -

Felix Warburg's Magic and the Kirkland Case

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 16, Number 32, August 11, 1989 of excusing him and his kind from changing their behavior. Balanchine's school in New York, and was promoted by the What is the basis of that behavior? The same as identified choreographer himself to the rank of ballerina. In 1986, Miss by the British intelligence profiling methods Wolfe utilizes Kirkland wrote an autobiography, Dancing on my Grave, in this novel. All characters' actions can be explained by which became a bestseller in the United States and was then Hobbesian-bestial-drives. Sex, money, family, power, republished in England, in Italy, and in Denmark, the har prestige, avoidance of pain, or the occasional death-wish shest attack on Georges Balanchine ever put into print. She motivates them all into every action, every public sortie or recalled that it was Balanchine himself who first introduced utterance, however silly or whatever the outcome. Each char her to drugs, pressing amphetamines into her hand before her acter's frame of reference for the sex, money, etc. is defined appearance in Leningrad, telling her they were just "head by his or her ethnic or racial background. It is a world of each ache pills." She stated that articles on Schiller's Aesthetics against all, only tempered by a tattered social contract and by Mrs. Helga Zepp-LaRouche, the wife of the controversial fast-fading traditions, and it is all coming undone at the American politician Lyndon LaRouche, had pushed her to seams. break with the drug world. Miss Kirkland, it now appears, No character is allowed to think of the future or base has been "blacklisted" by the music mafia. -

Senate the Senate Met at 9:45 A.M

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 108 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 150 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 14, 2004 No. 109 Senate The Senate met at 9:45 a.m. and was U.S. SENATE, ple to come in late. In order to finish called to order by the Honorable LIN- PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE, the bill, especially as we want to pay COLN D. CHAFEE, a Senator from the Washington, DC, September 14, 2004. appropriate respect to the Jewish holi- State of Rhode Island. To the Senate: day tomorrow, I plead with our col- Under the provisions of rule I, paragraph 3, of the Standing Rules of the Senate, I hereby leagues that they come as soon as they PRAYER appoint the Honorable LINCOLN D. CHAFEE, a are notified there will be a vote. We The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- Senator from the State of Rhode Island, to give everyone a heads-up when there fered the following prayer: perform the duties of the Chair. will be a vote. Come and vote and leave Let us pray. TED STEVENS, and efficiently use that time. O Lord, our rock, hear our praise President pro tempore. Mr. REID. Will the Senator yield? today, for Your faithfulness endures to Mr. CHAFEE thereupon assumed the Mr. FRIST. I am happy to yield for a all generations. You hear our prayers. chair as Acting President pro tempore. question. Mr. REID. Mr. President, I am so Surround us with Your mercy. -

Max Beckmann Alexej Von Jawlensky Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Fernand Léger Emil Nolde Pablo Picasso Chaim Soutine

MMEAISSTTEERRWPIECREKSE V V MAX BECKMANN ALEXEJ VON JAWLENSKY ERNST LUDWIG KIRCHNER FERNAND LÉGER EMIL NOLDE PABLO PICASSO CHAIM SOUTINE GALERIE THOMAS MASTERPIECES V MASTERPIECES V GALERIE THOMAS CONTENTS MAX BECKMANN KLEINE DREHTÜR AUF GELB UND ROSA 1946 SMALL REVOLVING DOOR ON YELLOW AND ROSE 6 STILLEBEN MIT WEINGLÄSERN UND KATZE 1929 STILL LIFE WITH WINE GLASSES AND CAT 16 ALEXEJ VON JAWLENSKY STILLEBEN MIT OBSTSCHALE 1907 STILL LIFE WITH BOWL OF FRUIT 26 ERNST LUDWIG KIRCHNER LUNGERNDE MÄDCHEN 1911 GIRLS LOLLING ABOUT 36 MÄNNERBILDNIS LEON SCHAMES 1922 PORTRAIT OF LEON SCHAMES 48 FERNAND LÉGER LA FERMIÈRE 1953 THE FARMER 58 EMIL NOLDE BLUMENGARTEN G (BLAUE GIEßKANNE) 1915 FLOWER GARDEN G (BLUE WATERING CAN) 68 KINDER SOMMERFREUDE 1924 CHILDREN’S SUMMER JOY 76 PABLO PICASSO TROIS FEMMES À LA FONTAINE 1921 THREE WOMEN AT THE FOUNTAIN 86 CHAIM SOUTINE LANDSCHAFT IN CAGNES ca . 1923-24 LANDSCAPE IN CAGNES 98 KLEINE DREHTÜR AUF GELB UND ROSA 1946 SMALL REVOLVING DOOR ON YELLOW AND ROSE MAX BECKMANN oil on canvas Provenance 1946 Studio of the Artist 60 x 40,5 cm Hanns and Brigitte Swarzenski, New York 5 23 /8 x 16 in. Private collection, USA (by descent in the family) signed and dated lower right Private collection, Germany (since 2006) Göpel 71 2 Exhibited Busch Reisinger Museum, Cambridge/Mass. 1961. 20 th Century Germanic Art from Private Collections in Greater Boston. N. p., n. no. (title: Leaving the restaurant ) Kunsthalle, Mannheim; Hypo Kunsthalle, Munich 2 01 4 - 2 01 4. Otto Dix und Max Beckmann, Mythos Welt. No. 86, ill. p. 156. -

Executive Intelligence Review, Volume 8, Number 10, March 10

[THIS PAGE IS INTENTIONALLY BLANK] , . ' Editor-in-chief: Criton Zoakos Associate Editor: Robyn Quijano Managing Editor: Susan Johnson Art Director: Martha Zoller Circulation Manager: Pamela Seawell Contributing Editors: Lyndon H. LaRouche, Jr., Christopher White, From the Editor Uwe Parpart, Nancy Spannaus Special Services: Peter Ennis INTELLIGENCE DIRECTORS: Africa: Douglas DeGroot Agriculture: Susan B. Cohen, Robert Ruschman Asia: Daniel Sneider Counterintelligence: Jeffrey Steinberg Economics: David Goldman Energy: William Engdahl A t the annual Wehrkunde conference in late February of military Europe: Vivian Zoakos spokesmen from the NATO alliance, West Germany laid down the Latin America: Dennis Small Law: Edward Spannaus law to Alexander Haig: there can be no adequate defense without Middle East: Robert Dreyfuss industrial recovery. This is the view most precisely and prominently Military Strategy: Susan Welsh Science and Technology: associated with EIR Contributing Editor Lyndon H. LaRouche, Jr., Marsha Freeman and with the findings of EIR's LaRouche-Riemann econometric Soviet Sector: Rachel Douglas studies. It was seconded at the Wehrkunde meeting by the chairman United States: Konstantin George of the Senate Armed Forces Committee, John Tower of Texas. But in INTERNATIONAL BUREAUS: Washington, the issue has not yet been faced. Bogota: Carlos Cota Meza Bonn: George Gregory, This week's Economics section examines several aspects of Amer Thierry LeMarc ica's investment crisis: the now-proven impossibility of maintaining a Chicago: Paul Greenberg Copenhagen: Vincent Robson "technetronic sunrise" sector without an industrial base; the devasta Houston: Timothy Richardson tion of the once-great industrial center of Detroit; and the impossibil Los Angeles: Theodore Andromidas ity, under Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker, of continuing Mexico City: Josefina Menendez Milan: Muriel Mirak even the patchwork financing that has kept remaining hard-commod Monterrey: M. -

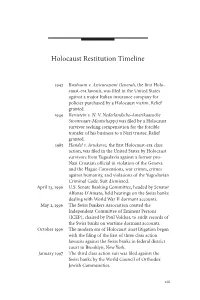

Holocaust Restitution Timeline

Holocaust Restitution Timeline 1942 Buxbaum v. Assicurazioni Generali, the first Holo- caust-era lawsuit, was filed in the United States against a major Italian insurance company for policies purchased by a Holocaust victim. Relief granted. 1949 Bernstein v. N. V. Nederlandsche-Amerikaansche Stoomvaart-Maatschappij was filed by a Holocaust survivor seeking compensation for the forcible transfer of his business to a Nazi trustee. Relief granted. 1985 Handel v. Artukovic, the first Holocaust-era class action, was filed in the United States by Holocaust survivors from Yugoslavia against a former pro- Nazi Croatian official in violation of the Geneva and the Hague Conventions, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and violations of the Yugoslavian Criminal Code. Suit dismissed. April 23, 1996 U.S. Senate Banking Committee, headed by Senator Alfonse D’Amato, held hearings on the Swiss banks dealing with World War II dormant accounts. May 2, 1996 The Swiss Bankers Association created the Independent Committee of Eminent Persons (ICEP), chaired by Paul Volcker, to audit records of the Swiss banks on wartime dormant accounts. October 1996 The modern era of Holocaust asset litigation began with the filing of the first of three class action lawsuits against the Swiss banks in federal district court in Brooklyn, New York. January 1997 The third class action suit was filed against the Swiss banks by the World Council of Orthodox Jewish Communities. xiii xiv Holocaust Restitution Timeline January 8, 1997 Christoph Meili discovered the Union Bank of Switzerland attempting to shred pre–World War II financial documents. March 25, 1997 French Prime Minister Alain Juppe created the Prime Minister’s Office Study Mission into the Looting of Jewish Assets in France (“Mattéoli Commission”) to study various forms of theft of Jewish property during World War II and the postwar efforts to remedy such theft. -

EIR Executive Intelligence Review Special Reports

EIR Executive Intelligence Review Special Reports The special reports listed below, prepared by the EIR staff, are now available. 1. Prospects for Instability in the Arabian Gulf 5. The Significance of the Shakeup at Pemex A comprehensive review of the danger of instabil EIR correctly forecast the political troubles of ity in Saudi Arabia in the coming period. Includes former Pemex director Jorge Diaz Serrano, and analysis of the Saudi military forces, and the in this report provides the full story of the recent fluence of left-wing forces, and pro-Khomeini net shakeup at Pemex.lncludes profile of new Pemex works in the country. $250. director Julio Rodolfo Moctezuma Cid, implica tions of the Pemex shakeup for the upcoming 2. Energy and Economy: Mexico in the Year 2000 presidential race, and consequences for Mexico's A development program for Mexico compiled energy policy. $200. jointly by Mexican and American scientists.Con cludes Mexico can grow at12 percent annually for 6. What is the Trilateral Commission? the next decade, creating a $100 billion capital The most complete analysis of the background, goods export market for the United States. De origins, and goals of this much-talked-about tailed analysis of key economic sectors; ideal for organization. Demonstrates the role of the com planning and marketing purposes. $250. mission in the Carter administration's Global 2000 report on mass population reduction; in the 3. Who Controls Environmentalism P-2 scandal that collapsed the Italian government A history and detailed grid of the environmental this year; and in the Federal Reserve's high ist movement in the United States.