Committed to Memory: Remembering "9/11" As a Crisis of Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title: Never Forget: Ground Zero, Park51, and Constitutive Rhetorics

Title: Never Forget: Ground Zero, Park51, and Constitutive Rhetorics Author: Tamara Issak Issue: 3 Publication Date: November 2020 Stable URL: http://constell8cr.com/issue-3/never-forget-ground-zero-park51-and-constitutive-rh etorics/ constellations a cultural rhetorics publishing space Never Forget: Ground Zero, Park51, and Constitutive Rhetorics Tamara Issak, St. John’s University Introduction It was the summer of 2010 when the story of Park51 exploded in the news. Day after day, media coverage focused on the proposal to create a center for Muslim and interfaith worship and recreational activities in Lower Manhattan. The space envisioned for Park51 was a vacant department store which was damaged on September 11, 2001. Eventually, it was sold to Sharif El-Gamal, a Manhattan realtor and developer, in July of 2009. El-Gamal intended to use this space to build a community center open to the general public, which would feature a performing arts center, swimming pool, fitness center, basketball court, an auditorium, a childcare center, and many other amenities along with a Muslim prayer space/mosque. Despite the approval for construction by a Manhattan community board, the site became a battleground and the project was hotly debated. It has been over ten years since the uproar over Park51, and it is important to revisit the event as it has continued significance and impact today. The main argument against the construction of the community center and mosque was its proximity to Ground Zero. Opponents to Park51 argued that the construction of a mosque so close to Ground Zero was offensive and insensitive because the 9/11 attackers were associated with Islam (see fig. -

Stephen Abraham, Lieutenant Colonel (Ret

As of June 24, 2010 Stephen Abraham , Lieutenant Colonel (Ret.), U.S. Army Intelligence Corps (Reserves); Lawyer, Newport Beach, California Morton Abramowitz , Senior Fellow, The Century Foundation; former President, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace; Ambassador to Turkey, 1989-1991, Thailand, 1978- 1981 and to the Mutual and Balanced Force Reduction Negotiations in Vienna, 1983- 1984; former Assistant Secretary of State for Intelligence and Research; former Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Inter-American, East Asian, and Pacific affairs; former Special Assistant to the Secretary of Defense and to the Deputy Secretary of State; former political adviser to the Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Azizah al-Hibri , Professor, The T.C. Williams School of Law, University of Richmond; President, Karamah: Muslim Women Lawyers for Human Rights Dennis Archer , President, American Bar Association, 2003-2004; Mayor, Detroit, 1994- 2001; Associate Justice, Michigan Supreme Court, 1986-1990 J. Brian Atwood , Dean, Humphrey Institute; former Administrator, U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID); head of transition team, State Department; former Under Secretary of State for Management; former Adjunct Lecturer at Harvard's JFK School; former Sol M. Linowitz Professor for International Affairs, Hamilton College; Director, Citizens International Lourdes G. Baird , Judge, U.S. District Court for the Central District of California, 1992- 2005, Los Angeles Superior Court, 1988-1990, Los Angeles Municipal Court, 1987-1988, and Municipal Court, East Los Angeles Judicial District, 1986-1987; U.S. Attorney, Central District of California, 1990-1992; Assistant U.S. Attorney, Central District of California, 1977-1983 Doug Bandow , former Special Assistant to President Ronald Reagan William Banks , Professor, Director, the Institute for National Security and Counterterrorism; Laura J. -

Discussion and Study Guide in OUR SON’S NAME a Film by Gayla Jamison

Discussion and Study Guide IN OUR SON’S NAME A Film by Gayla Jamison Forgiveness means recognizing the full humanity of the other person. It also means letting go of something that can be self-destructive. How to This discussion and study guide is intended to accompany the documentary Use This film In Our Son’s Name when used by community groups, schools, churches, synagogues, mosques, and prisons. It includes suggestions on how to use Guide this guide, a statement from director Gayla Jamison, and a synopsis. Also included are a chronological timeline of events depicted in the film, a list of people who appear in the film with their photos, and a brief explanation of the death penalty trial process. The film inspires lively discussions by audiences wherever it’s shown. Many of the discussion questions included here are ones sparked by early screen- ings. Discussion questions are organized in two parts, as questions relating to specific scenes and questions pertaining to the film as a whole. Questions about specific scenes follow a brief description of the scene and are accom- panied by a representative still photo from that scene. The questions cover a variety of topics. Discussion leaders are encouraged to review the questions and select ones suited to their particular group and/or the direction they would like the discussion to take. Audiences have especially been moved by the prison sequences in the film. A version of how to implement the Peace Circle exercise that is seen in the prison sequences is included here. That section also includes Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about the Circle Process, a brief explanation of the concept of restorative justice, and excerpts from letters from two of the Sing Sing prisoners who participated in the Circle Process shown in the film. -

Writing the 9/11 Decade

1 Writing the 9/11 Decade Charlie Lee-Potter A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of PhD ROYAL HOLLOWAY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 2 Declaration of Authorship I Charlie Lee-Potter hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: ______________________ Date: ________________________ 3 Charlie Lee-Potter, Writing the 9/11 Decade Novelists have struggled to find forms of expression that would allow them to register the post-9/11 landscape. This thesis examines their tentative and sometimes faltering attempts to establish a critical distance from and create a convincing narrative and metaphorical lexicon for the historical, political and psychological realities of the terrorist attacks. I suggest that they have, at times, been distracted by the populist rhetoric of journalistic expression, by a retreat to American exceptionalism and by the demand for an immediate response. The Bush administration’s statement that the state and politicians ‘create our own reality’ served to reinforce the difficulties that novelists faced in creating their own. Against the background of public commentary post-9/11, and the politics of the subsequent ‘War on Terror’, the thesis considers the work of Richard Ford, Paul Auster, Kamila Shamsie, Nadeem Aslam, Don DeLillo, Mohsin Hamid and Amy Waldman. Using my own extended interviews with Ford, Waldman and Shamsie, the artist Eric Fischl, the journalist Kevin Marsh, and with the former Archbishop of Canterbury Dr. Rowan Williams (who is also a 9/11 survivor), I consider the aims and praxis of novelists working within a variety of traditions, from Ford’s realism and Auster’s metafiction to the post- colonial perspectives of Hamid and Aslam, and, finally, the end-of-decade reflections of Waldman. -

Friedrichs Plaintiffs Change of Plan CUNY's

NEW! ● Change of plan WF prescription provider replaced larıon PAGE 8 CNEWSPAPER OF THE PROFESSIONAL STAFF CONGRESS / CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK DECEMBER 2015 Erik McGregor Erik PSC POWER GROWS WE SHALL NOT BE MOVED In its fight for a fair contract, PSC is ratcheting up the pressure with a series disorderly conduct. Plans for the action resulted in contract offer from CUNY of escalating tactics. In the scene above, members engaged in a planned civil management – one described as ‘unacceptable’ by PSC President Barbara disobedience action on November 4, blocking the entrance to CUNY head- Bowen. On November 19, members packed The Great Hall at the Cooper quarters in Midtown, risking arrest. Fifty-three members were charged with Union to begin preparations for a strike authorization vote. PAGES 3 & 6 FIGHT FOR $15 CHURCH & STATE DETERMINATION POWER & ART CUNY’s low- Friedrichs Ready for Irony meets wage workers plaintiffs action idealism The University employs Pressing the anti-union Su- At a union-wide meeting, 900 PSC member and MacAr- 7,000 workers at less than preme Court case is a little- PSC members gathered to thur Fellow Ben Lerner talks the rate set by activists known group that seeks to prepare for a strike autho- to Clarion about the rela- calling for a raise in the bring religion into public rization vote – the next big tionship between poetry and minimum wage. Read schools, making missionar- step in the union’s campaign politics, and the beauty of their stories. PAGE 5 ies of teachers. PAGE 9 for a fair contract. PAGE 3 imperfect collectivity. PAGE 12 AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF UNIVERSITY PROFESSORS ● AMERICAN FEDERATION OF TEACHERS ● NATIONAL EDUCATION ASSOCIATION ● NYC CENTRAL LABOR COUNCIL ● NYS AFL-CIO ● NEW YORK STATE UNITED TEACHERS 2 NEWS & LETTERS Clarion | December 2015 IN BRIEF LETTERS TO THE EDITOR | WRITE TO: CLARION/PSC, 61 BROADWAY, 15TH FLOOR, NEW YORK, NY 10006. -

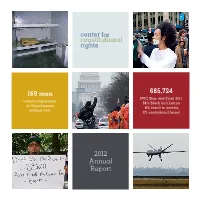

CCR Annual Report 2012

169 men 685,724 NYC Stop and Frisk 2011 remain imprisoned 84% Black and Latino at Guantánamo 6% result in arrests without trial 2% contraband found 2012 Annual Report The Center for Constitutional Rights is dedicated to advancing and protecting the rights guaranteed by the United States Constitution and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Founded in 1966 by attorneys who represented civil rights movements in the South, CCR is a non-profit legal and educational organization committed to the creative use of law as a positive force for social change. www.CCRjustice.org table of contents Letter from the Executive Director ........................................................................................ 2 Guantánamo .............................................................................................................................. 4 International Human Rights ................................................................................................... 8 Government Misconduct and Racial Injustice ................................................................ 12 Movement Support .................................................................................................................. 16 Social Justice Institute ........................................................................................................... 18 Communications .................................................................................................................... 20 Letter from the Legal Director ............................................................................................. -

1 Cultural & Social Affairs Department Oic

Cultural & social affairs Department OIC islamophobia Observatory Monthly Bulletin – APRIL 2014 I. Manifestations of Islamophobia: I.I. In the Americas: 1. Canada: Anti-Islamic pamphleteer gets nine months for promoting hate, but can still hand out flyers – A man charged for handing out anti-Islam flyers in Toronto was sentenced on 1st April to nine months in jail for promoting hate, among other charges, but was still allowed to hand out his flyers. In February 2014, Eric Brazau, 49, was convicted of willful promotion of hatred, criminal harassment, mischief and breach of probation by failing to keep the peace. He was charged in September, 2012. The judge called Mr. Brazau’s conduct “despicable,” but rejected the Crown’s suggestion to stop Mr. Brazau from making and handing out the flyers because it would have imposed on him a higher standard than the Criminal Code’s section on the wilful promotion of hatred. Justice Ford Clements said: “Brazau’s speech and pamphlets not only vilified Muslims but demonstrate prejudice, intolerance and insensitivity towards Muslims and their religious values.” Mr. Brazau had already served nine months in pre-trial custody and said he would be appealing the sentence. Judge Clements said the court did not have the right to moderate Mr. Brazau’s views, “as repugnant as they are,” and excluded the Crown’s suggestion that his probation included counselling and community service. In: http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/toronto/anti-islamic-pamphleteer-gets-nine-months-for-promoting-hate-but-can-still-hand-out- flyers/article17760151/, retrieved on 03.04.2014 2. -

Islamophobia & Muslims' Religious Experiences In

ISLAMOPHOBIA & MUSLIMS‘ RELIGIOUS EXPERIENCES IN THE MIDWEST— PROPOSING CRITICAL MUSLIM THEORY A MUSLIM AUTOETHNOGRAPHY by MOHAMAD RIDHUAN ABDULLAH B.Ed. (TESL), University Technology of MARA, 2003 M.S., Kansas State University, 2009 AN ABSTRACT OF A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Curriculum and Instruction College of Education KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2013 Abstract This study explored Islamophobia and Muslims‘ religious experiences in the Midwest. Its purpose was to propose a new theory named Critical Muslim Theory. The research methodology was autoethnography (me, the researcher) in concert with discovering in-depth experiences and narratives of nine Muslim participants (five Muslim females and four Muslim males) in dealing with Islamophobia. Religion became the centrality of Critical Muslim Theory in replacing race (as in Critical Race Theory) while centralizing other oppressions Muslims experience through intersections with religion and law, religion and gender, and religion and race. Critical Muslim Theory represents six basic tenets, namely: (a) Islamophobia is endemic and pervasive, (b) Critical Muslim Theory is critical towards how the dominant society views Islam and Muslims, (c) Islamophobia is a social construction, (d) Legal basis, (e) Intersectionality, and (f) Storytelling and counterstories reveal the oppression and pain of Muslims. An historical context was established for Muslims in the United States of America, although more research needs to be contributed to this area. Instances of interest convergence also were present, however, more research in this area is needed. One recommendation from this research suggests combating ignorance through education and establishing a pure relationship between Muslims and non- Muslims through dialogue for understanding. -

Ground Zero Mosque” and the Problem with Tolerance

Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies ISSN: 1479-1420 (Print) 1479-4233 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rccc20 Good Muslims, Bad Muslims, and the Nation: The “Ground Zero Mosque” and the Problem With Tolerance Chris Earle To cite this article: Chris Earle (2015) Good Muslims, Bad Muslims, and the Nation: The “Ground Zero Mosque” and the Problem With Tolerance, Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies, 12:2, 121-138, DOI: 10.1080/14791420.2015.1008529 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14791420.2015.1008529 Published online: 04 Feb 2015. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 378 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rccc20 Download by: [University of Michigan] Date: 11 December 2015, At: 13:42 Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies Vol. 12, No. 2, June 2015, pp. 121–138 Good Muslims, Bad Muslims, and the Nation: The “Ground Zero Mosque” and the Problem With Tolerance Chris Earle The local controversy over Cordoba House or the “Ground Zero Mosque” peaked at a May 2010 Lower Manhattan Community Board meeting that was open to the public. Examining the tolerance rhetorics evoked both for and against Cordoba, this paper argues that both tolerance rhetorics function differently to re-center the white non- Muslim subject and to structure inclusion and belonging within the nation. Extending the literature of tolerance, which tends to focus on the discourse of normative subjects, I analyze the tolerance rhetorics of two Muslim-American rhetors whose testimonies reveal the tensions, contradictions, and complicities involved in claims of national belonging. -

Compilation of Hearings on Islamist Radicalization—Volume I

COMPILATION OF HEARINGS ON ISLAMIST RADICALIZATION—VOLUME I HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TWELFTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION MARCH 10, JUNE 15, and JULY 27, 2011 Serial No. 112–9 Printed for the use of the Committee on Homeland Security Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/ COMPILATION OF HEARINGS ON ISLAMIST RADICALIZATION—VOLUME I COMPILATION OF HEARINGS ON ISLAMIST RADICALIZATION—VOLUME I HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TWELFTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION MARCH 10, JUNE 15, and JULY 27, 2011 Serial No. 112–9 Printed for the use of the Committee on Homeland Security Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 72–541 PDF WASHINGTON : 2012 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY PETER T. KING, New York, Chairman LAMAR SMITH, Texas BENNIE G. THOMPSON, Mississippi DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California LORETTA SANCHEZ, California MIKE ROGERS, Alabama SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas HENRY CUELLAR, Texas GUS M. BILIRAKIS, Florida YVETTE D. CLARKE, New York PAUL C. BROUN, Georgia LAURA RICHARDSON, California CANDICE S. MILLER, Michigan DANNY K. DAVIS, Illinois TIM WALBERG, Michigan BRIAN HIGGINS, New York CHIP CRAVAACK, Minnesota JACKIE SPEIER, California JOE WALSH, Illinois CEDRIC L. RICHMOND, Louisiana PATRICK MEEHAN, Pennsylvania HANSEN CLARKE, Michigan BEN QUAYLE, Arizona WILLIAM R. -

Stolen Freedoms: Arabs, Muslims, and South Asians in the Wake of Post 9/11 Backlash

Denver Law Review Volume 81 Issue 4 Symposium - Post-9/11 Civil Rights Article 3 December 2020 Stolen Freedoms: Arabs, Muslims, and South Asians in the Wake of Post 9/11 Backlash Dalia Hashad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/dlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Dalia Hashad, Stolen Freedoms: Arabs, Muslims, and South Asians in the Wake of Post 9/11 Backlash, 81 Denv. U. L. Rev. 735 (2004). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denver Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. STOLEN FREEDOMS: ARABS, MUSLIMS, AND SOUTH ASIANS IN THE WAKE OF POST 9/11 BACKLASH DALIA HASHADt Since 9/11, the United States government's "War on Terror" has, in large part, been an attack on innocent Arabs, people from the Middle East and South Asia, and Muslims. Using race, ethnicity and religion as a proxy for criminal behavior, law enforcement has zeroed in on people of certain ethnicities and a single faith. The Department of Justice (DOJ), now engulfed in the Department of Homeland Security, has rolled out programs and established policies that target, harass and in many in- stances, make life miserable for Arabs and Muslims in this country. The overwhelming majority in these groups are innocent of any criminal ac- tivity, however their persecution by zealous law enforcement results in thousands of needless tragedies. For every day that has passed since 9/11, there are dozens of painful stories borne of government-instituted discrimination and racist implementation of policy. -

September 11 Families For

th September 11 Families for 2016 Media Excerpts She lost her nephew 15 years ago: September 11 split us interview SIDSEL NYHOLM WRITES FROM USA http://www.kristeligt-dagblad.dk/udland/hun-mistede-sin-nevoe-15-aar-siden-11.-september-splittede-os 10 September 2016 Memories of the terrorist attack on the United States September 11, 2001 fade, but for Valerie Lucznikowska who lost his nephew in the attack, is the 15th anniversary tomorrow a bitter reminder of the discord which aftermath created in American society and in her own family. "The militarism that was the answer to the attack on us, divided us as a people. There are some very fundamental differences in our world view, "says Valerie Lucznikowska who lost his nephew during the terrorist attack. She lost her confidence in the United States as a nation that puts freedom rights above all other considerations. Invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, the revelations of the US use of secret prisons and torture, and the overall dilution of Americans' civil rights in the wake of the terrorist attack, disappointed her deeply. She also lost most of his immediate family, as her activism for peace and understanding was met with displeasure by the more politically conservative relatives. As a member of the kin group September 11th Families for Peaceful Tomorrows (September 11 Families for a peaceful future), whose purpose is to create a dialogue about alternatives to war, Valerie Lucznikowska by her own admission is disinterested in revenge… THE DEADLY ATTACK: The World Trade Center Twin towers hours after the smoke and dust had cleared following the attacks of September 11, 2001.