Henry Thoreau, Ralph Ellison, and Jonathan Lethem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Immortal Jellyfish and Other Things That Don't Know About Love

Northern Michigan University NMU Commons All NMU Master's Theses Student Works 4-2018 The mmorI tal Jellyfish and Other Things That Don't Know About Love Tianli Kilpatrick Northern Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.nmu.edu/theses Part of the Nonfiction Commons Recommended Citation Kilpatrick, Tianli, "The mmorI tal Jellyfish and Other Things That Don't Know About Love" (2018). All NMU Master's Theses. 538. https://commons.nmu.edu/theses/538 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at NMU Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in All NMU Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of NMU Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. THE IMMORTAL JELLYFISH AND OTHER THINGS THAT DON’T KNOW ABOUT LOVE By Tianli Quinn Kilpatrick THESIS Submitted to Northern Michigan University In Partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Office of Graduate Education and Research April 2018 © 2018 Tianli Kilpatrick ABSTRACT THE IMMORTAL JELLYFISH AND OTHER THINGS THAT DON’T KNOW ABOUT LOVE By Tianli Quinn Kilpatrick My thesis is a collection of creative nonfiction essays that play with form and language in an attempt to show that trauma can create beauty. This thesis originated with trauma theory and specifically deals with sexual assault trauma, but it also covers topics including international adoption, self-injury, and oceanic life. Jellyfish are a recurring image and theme, both the physical jellyfish itself and the mythological connection to Medusa. -

“No Reason to Be Seen”: Cinema, Exploitation, and the Political

“No Reason to Be Seen”: Cinema, Exploitation, and the Political by Gordon Sullivan B.A., University of Central Florida, 2004 M.A., North Carolina State University, 2007 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2017 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Gordon Sullivan It was defended on October 20, 2017 and approved by Marcia Landy, Distinguished Professor, Department of English Jennifer Waldron, Associate Professor, Department of English Daniel Morgan, Associate Professor, Department of Cinema and Media Studies, University of Chicago Dissertation Advisor: Adam Lowenstein, Professor, Department of English ii Copyright © by Gordon Sullivan 2017 iii “NO REASON TO BE SEEN”: CINEMA, EXPLOITATION, AND THE POLITICAL Gordon Sullivan, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2017 This dissertation argues that we can best understand exploitation films as a mode of political cinema. Following the work of Peter Brooks on melodrama, the exploitation film is a mode concerned with spectacular violence and its relationship to the political, as defined by French philosopher Jacques Rancière. For Rancière, the political is an “intervention into the visible and sayable,” where members of a community who are otherwise uncounted come to be seen as part of the community through a “redistribution of the sensible.” This aesthetic rupture allows the demands of the formerly-invisible to be seen and considered. We can see this operation at work in the exploitation film, and by investigating a series of exploitation auteurs, we can augment our understanding of what Rancière means by the political. -

JOHN SURMAN Title: FLASHPOINT: NDR JAZZ WORKSHOP – APRIL '69 (Cuneiform Rune 315-316)

Bio information: JOHN SURMAN Title: FLASHPOINT: NDR JAZZ WORKSHOP – APRIL '69 (Cuneiform Rune 315-316) Cuneiform publicity/promotion dept.: (301) 589-8894 / fax (301) 589-1819 email: joyce [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com [Press & world radio]; radio [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com [North American radio] www.cuneiformrecords.com FILE UNDER: JAZZ One of Europe’s foremost jazz musicians, John Surman is a masterful improvisor, composer, and multi-instrumentalist (baritone and soprano sax, bass clarinet, and synthesizers/electronics). For 45 years, he has been a major force, producing a prodigious and creative body of work that expands beyond jazz. Surman’s extensive discography as a leader and a side man numbers more than 100 recordings to date. Surman has worked with dozens of prominent artists worldwide, including John McLaughlin, Chick Corea, Chris McGregor’s Brotherhood of Breath, Dave Holland, Miroslav Vitous, Jack DeJohnette, Terje Rypdal, Weather Report, Karin Krog, Bill Frisell, Paul Motian and many more. Surman is probably most popularly known for his longstanding association with the German label ECM, who began releasing Surman’s recordings in 1979. Surman has won numerous jazz polls and awards and a number of important commissions. Every period of his career is filled with highlights, which is why Cuneiform is exceedingly proud to release for the first time ever this amazing document of the late 60s 'Brit-jazz' scene. Born in Tavistock, in England, Surman discovered music as a child, singing as soprano soloist in a Plymouth-area choir. He later bought a second- hand clarinet, took lessons from a Royal Marine Band clarinetist, and began playing traditional Dixieland jazz at local jazz clubs. -

2021 Made for the Game

MADE FOR THE GAME 2021 BALL CONSTRUCTION LAMINATED 1. COVER Laminated construction uses leather 1 The cover material provides su- CONTENTS or composite panels. These panels perior grip and soft feel while are fixed onto a rubber carcass by maintaining our rigorous stan- hand in order to provide athletes dards for material strength SIZES 1 2 BALL CONSTRUCTION 2 with the highest quality basketballs and abrasion resistance. ICONS 2 available. The versatility of this COVER MATERIAL 3 ball construction gives players the ability to take their game to the next 2. CARCASS 3 INFLATES 3 level. The carcass provides Target: Competitive Play 4 structure, shape and protection MODEL M 3 for the inner components. TF SERIES 7 TF TRAINER 9 ZiO 10 MOLDED 1/2 3. WINDINGS ALL CONFERENCE 11 NEVERFLAT™ 12 Molded construction is used on Windings add structural integ- STREET PHANTOM 13 outdoor basketballs and provides rity and durability to the con- STREET 14 increased design capabilities and a struction of the ball. MARBLE 15 wide range of available color 3 VARSITY 16 and graphic options. 4. BLADDER LAYUP MINI 17 Target: Recreational Play YOUTH 18 The high-end bladder SPALDEEN 19 maintains the ball’s air pres- 4 sure for proper inflation and PROMOTIONAL ITEMS 19 extended air retention. ICONS An indoor ball is designed exclusively Colored rubber with a unique color mixing for indoor playing surfaces. These balls tech nique that makes each ball different are constructed with leather or high-end from the next. composite covers. SIZES Outdoor basketballs have a durable Balls approved by the National cover that can withstand rougher Federation of High School SIZE AGE CATEGORY playing surfaces. -

An Annotated Bibliography of Works by the Brazilian Composer Sérgio Assad João Paulo Figueirôa Da Cruz

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 An Annotated Bibliography of Works by the Brazilian Composer Sérgio Assad João Paulo Figueirôa Da Cruz Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY OF WORKS BY THE BRAZILIAN COMPOSER SÉRGIO ASSAD By João Paulo Figueirôa da Cruz A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2008 Copyright © 2008 João Paulo Figueirôa da Cruz All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the treatise of João Paulo Figueirôa da Cruz defended on June 17, 2008. ______________________________________ Evan Jones Professor Directing Treatise ______________________________________ James Mathes Outside Committee Member ______________________________________ Bruce Holzman Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee member ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation would have not been possible without the support of many individuals who helped this project. I would like to thank Hanh Hoang for her assistance in the concretization of this document and Byron Fogo for his kindness to offer his help in this project. I do not have words to express my gratitude to all my committee members. I want to thank Dr. Jones for his devotion and wisdom directing this work, Dr. Mathes for agreeing to join the committee at the last minute, Dr. Olsen for his help and support during the years and finally Prof. Holzman for all these years which he gave his best to me! I would like to thank Fábio Zanon, Luciano César Morais and Thiago Oliveira for offering important research material for this project. -

I Attended Church Several Times on Sunday Mornings at University Methodist at the Corner of Guadalupe and 24Thstreets

First Encounter During the time I was in Austin as a UT grad student (1955-57) I attended church several times on Sunday mornings at University Methodist at the corner of Guadalupe and 24thstreets. In the fall of 1956 I also investigated programs at Wesley Foundation, the Methodist Church chaplaincy division for students. After the first session I attended, the larger group broke up into smaller “interest groups.” Many went with a leader who seemed quite popular (I later learned his name was Bob Ledbetter). I joined a smaller group (about six or eight people) led by an associate pastor at University Methodist, the Rev. Richardson. We’d discuss art in religion, particularly various paintings of the image of Jesus. Two in particular that I remember we looked at were the famous Salmon’s Head of Christ and another painted by the French artist Georges Roualt. For both paintings the Rev. Richardson conducted what I’d later realize to be an “art form” conversation. Obviously, although I didn’t know it at the time, he’d had contact with Austin’s Christian Faith and Life Community and its charismatic theological director, Joseph W. Mathews. In the conversation our study group came to the conclusion that Salmon’s painting was sentimental and schmaltzy and that Roualt’s (“Christ Mocked by Soldiers”) was more powerful. Ecumenical Institute Introduction As a grad student at the University of Minnesota (1961-67) I attended the of First Methodist Church and Wesley Foundation. A Mrs. Peel had left money in her will to bring to the church each year a special preacher. -

The Dark Night of the Soul: the Archetype and Its Occurrence in Modern Fiction

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1973 The aD rk Night of the Soul: the Archetype and Its Occurrence in Modern Fiction. Ibry Glyn-francis Theriot Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Theriot, Ibry Glyn-francis, "The aD rk Night of the Soul: the Archetype and Its Occurrence in Modern Fiction." (1973). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2577. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2577 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

My Town: Writers on American Cities

MY TOW N WRITERS ON AMERICAN CITIES MY TOWN WRITERS ON AMERICAN CITIES CONTENTS INTRODUCTION by Claire Messud .......................................... 2 THE POETRY OF BRIDGES by David Bottoms ........................... 7 GOOD OLD BALTIMORE by Jonathan Yardley .......................... 13 GHOSTS by Carlo Rotella ...................................................... 19 CHICAGO AQUAMARINE by Stuart Dybek ............................. 25 HOUSTON: EXPERIMENTAL CITY by Fritz Lanham .................. 31 DREAMLAND by Jonathan Kellerman ...................................... 37 SLEEPWALKING IN MEMPHIS by Steve Stern ......................... 45 MIAMI, HOME AT LAST by Edna Buchanan ............................ 51 SEEING NEW ORLEANS by Richard Ford and Kristina Ford ......... 59 SON OF BROOKLYN by Pete Hamill ....................................... 65 IN SEATTLE, A NORTHWEST PASSAGE by Charles Johnson ..... 73 A WRITER’S CAPITAL by Thomas Mallon ................................ 79 INTRODUCTION by Claire Messud ore than three-quarters of Americans live in cities. In our globalized era, it is tempting to imagine that urban experiences have a quality of sameness: skyscrapers, subways and chain stores; a density of bricks and humanity; a sense of urgency and striving. The essays in Mthis collection make clear how wrong that assumption would be: from the dreamland of Jonathan Kellerman’s Los Angeles to the vibrant awakening of Edna Buchanan’s Miami; from the mid-century tenements of Pete Hamill’s beloved Brooklyn to the haunted viaducts of Stuart Dybek’s Pilsen neighborhood in Chicago; from the natural beauty and human diversity of Charles Johnson’s Seattle to the past and present myths of Richard Ford’s New Orleans, these reminiscences and musings conjure for us the richness and strangeness of any individual’s urban life, the way that our Claire Messud is the author of three imaginations and identities and literary histories are intertwined in a novels and a book of novellas. -

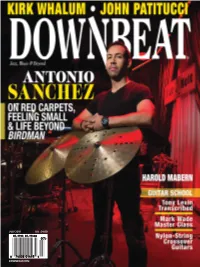

Downbeat.Com July 2015 U.K. £4.00

JULY 2015 2015 JULY U.K. £4.00 DOWNBEAT.COM DOWNBEAT ANTONIO SANCHEZ • KIRK WHALUM • JOHN PATITUCCI • HAROLD MABERN JULY 2015 JULY 2015 VOLUME 82 / NUMBER 7 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer ĺDQHWDÎXQWRY£ Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Bookkeeper Emeritus Margaret Stevens Editorial Assistant Stephen Hall ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, -

John O'donohue Anam Cara

John O’Donohue Anam Cara A Book of Celtic Wisdom BEANNACHT For Josie On the day when the weight deadens on your shoulders and you stumble, may the clay dance to balance you. And when your eyes freeze behind the gray window and the ghost of loss gets in to you, may a flock of colors, indigo, red, green and azure blue come to awaken in you a meadow of delight. When the canvas frays in the curach of thought and a stain of ocean blackens beneath you, may there come across the waters a path of yellow moonlight to bring you safely home. May the nourishment of the earth be yours, may the clarity of light be yours, may the fluency of the ocean be yours, may the protection of the ancestors be yours. And so may a slow wind work these words of love around you, an invisible cloak to mind your life. In memory of my father, Paddy O’Donohue, who worked stone so poetically, and my uncle Pete O’Donohue, who loved the mountains And my aunt Brigid In memory of John, Willie, Mary, and Ellie O’Donohue, who emigrated and now rest in American soil Contents Acknowledgments Prologue 1 The Mystery of Friendship Light Is Generous The Celtic Circle of Belonging The Human Heart Is Never Completely Born Love Is the Nature of the Soul The Umbra Nihili The Anam Cara Intimacy as Sacred The Mystery of Approach Diarmuid and Gráinne Love as Ancient Recognition The Circle of Belonging The Kalyana-mitra The Soul as Divine Echo The Wellspring of Love Within The Transfiguration of the Senses The Wounded Gift In the Kingdom of Love, There Is No Competition 2 Toward a Spirituality -

The Interviews

Jeff Schechtman Interviews December 1995 to April 2017 2017 Marcus du Soutay 4/10/17 Mark Zupan Inside Job: How Government Insiders Subvert the Public Interest 4/6/17 Johnathan Letham More Alive and Less Lonely: On Books and Writers 4/6/17 Ali Almossawi Bad Choices: How Algorithms Can Help You Think Smarter and Live Happier 4/5/17 Steven Vladick Prof. of Law at UT Austin 3/31/17 Nick Middleton An Atals of Countries that Don’t Exist 3/30/16 Hope Jahren Lab Girl 3/28/17 Mary Otto Theeth: The Story of Beauty, Inequality and the Struggle for Oral Health 3/28/17 Lawrence Weschler Waves Passing in the Night: Walter Murch in the Land of the Astrophysicists 3/28/17 Mark Olshaker Deadliest Enemy: Our War Against Killer Germs 3/24/17 Geoffrey Stone Sex and Constitution 3/24/17 Bill Hayes Insomniac City: New York, Oliver and Me 3/21/17 Basharat Peer A Question of Order: India, Turkey and the Return of the Strongmen 3/21/17 Cass Sunstein #Republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media 3/17/17 Glenn Frankel High Noon: The Hollywood Blacklist and the Making of an American Classic 3/15/17 Sloman & Fernbach The Knowledge Illusion: Why We Think Alone 3/15/17 Subir Chowdhury The Difference: When Good Enough Isn’t Enough 3/14/17 Peter Moskowitz How To Kill A City: Gentrification, Inequality and the Fight for the Neighborhood 3/14/17 Bruce Cannon Gibney A Generation of Sociopaths: How the Baby Boomers Betrayed America 3/10/17 Pam Jenoff The Orphan's Tale: A Novel 3/10/17 L.A. -

Emily S. Fine

Running head: THE DRIVE TO WRITE The Drive to Write: Inside the Writing Lives of Five Fiction Authors by Emily S. Fine B.A., Oberlin College, 2004 M.S., Antioch University New England, 2011 DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment for the degree of Doctor of Psychology in the Department of Clinical Psychology at Antioch University New England, 2015 Keene, New Hampshire THE DRIVE TO WRITE ii Department of Clinical Psychology DISSERTATION COMMITTEE PAGE The undersigned have examined the dissertation entitled: THE DRIVE TO WRITE: INSIDE THE WRITING LIVES OF FIVE FICTION AUTHORS presented on December 10, 2015 by Emily S. Fine Candidate for the degree of Doctor of Psychology and hereby certify that it is accepted*. Dissertation Committee Chairperson: Theodore Ellenhorn, PhD Dissertation Committee members: Barbara Belcher-Timme, PsyD Daniel Greif, PsyD Accepted by the Department of Clinical Psychology Chairperson George Tremblay, PhD on 12/10/15 * Signatures are on file with the Registrar’s Office at Antioch University New England. THE DRIVE TO WRITE iii Acknowledgments First and foremost, I am exceedingly grateful to the authors who participated in this study for offering me a glimpse into their writing processes and inner lives. Thank you to Richard Russo, Christopher Paolini, Tova Mirvis, Jonathan Lethem, and Mary Doria Russell. Your authenticity, openness, and insight inspired and sustained me. Thank you to my advisor, Ted Ellenhorn, and my committee, Barbara Belcher-Timme and Daniel Greif, for patiently awaiting the final product. You encouraged but didn’t pressure me, which is exactly what I needed at this phase in my life and academic career.