Cultural Resources Regional Background

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring/Summer 2018

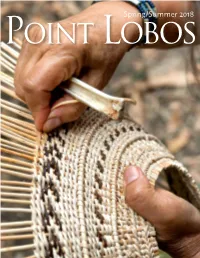

Spring/Summer 2018 Point Lobos Board of Directors Sue Addleman | Docent Administrator Kit Armstrong | President Chris Balog Jacolyn Harmer Ben Heinrich | Vice President Karen Hewitt Loren Hughes Diana Nichols Julie Oswald Ken Ruggerio Jim Rurka Joe Vargo | Secretary John Thibeau | Treasurer Cynthia Vernon California State Parks Liaison Sean James | [email protected] A team of State Parks staff, Point Lobos Docents and community volunteers take a much-needed break after Executive Director restoring coastal bluff habitat along the South Shore. Anna Patterson | [email protected] Development Coordinator President’s message 3 Tracy Gillette Ricci | [email protected] Kit Armstrong Docent Coordinator and School Group Coordinator In their footsteps 4 Melissa Gobell | [email protected] Linda Yamane Finance Specialist Shell of ages 7 Karen Cowdrey | [email protected] Rae Schwaderer ‘iim ‘aa ‘ishxenta, makk rukk 9 Point Lobos Magazine Editor Reg Henry | [email protected] Louis Trevino Native plants and their uses 13 Front Cover Chuck Bancroft Linda Yamane weaves a twined work basket of local native plant materials. This bottomless basket sits on the rim of a From the editor 15 shallow stone mortar, most often attached to the rim with tar. Reg Henry Photo: Neil Bennet. Notes from the docent log 16 Photo Spread, pages 10-11 Compiled by Ruthann Donahue Illustration of Rumsen life by Linda Yamane. Acknowledgements 18 Memorials, tributes and grants Crossword 20 Ann Pendleton Our mission is to protect and nurture Point Lobos State Natural Reserve, to educate and inspire visitors to preserve its unique natural and cultural resources, and to strengthen the network of Carmel Area State Parks. -

Record Packet Copy

STATE OF CALIFORNIA THE RESOURCES AGENCY GRAY DAVIS, GOVERNOR ' CALIFORNIA COASTAL COMMISSION 45 FREMONT, SUITE 2000 SAN FRANCISCO, CA 941 05· 2219 ICE AND TOO (415) 904· 5200 X ( 415) 904· 5400 • W12a RECORD PACKET COPY Date Filed: 6112/01 49th Day: 7/31/01 180th Day: 12/9/01 Staff: MVC-SF Staff Report: 7/19/01 Hearing Date: 8/8/01 Commission ActionJVote: Approved with conditions, 9-0 REVISED FINDINGS Application No.: E-01-008 Project Applicant: Monterey Abalone Company Project Location: Municipal Wharf #2, Monterey Harbor, Monterey County • Project Description: Construct and operate an abalone grow-out facility to cultivate up to 500,000 red abalone in Monterey Harbor, including the installation of walkways and seawater pumping system under the wharf and placement of concrete moorings on the seafloor. Substantive File Documents: Appendix B Prevailing Commissioners: Dettloff, Allgood, Hart, Lee, McCoy, Potter, Reilly, Woolley, Wan SYNOPSIS The Monterey Abalone Company ("MAC") proposes to construct and operate a facility to cultivate up to 500,000 red abalone (Haliotis rufescens) from juveniles to maturity in two types of "culture units," barrels and cages, to be suspended in the water under Municipal Wharf #2 in Monterey Harbor. Monterey Harbor is located 110 miles south of San Francisco in Monterey Bay in Monterey County, adjacent to the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary (Exhibit 1, "Project Location"). The MAC has been operating its facility since 1992 without benefit of a coastal development • permit. In this application, the MAC proposes to authorize its existing operations (the culture of E-01-008 (Monterey Abalone Company) ~e2~1 • approximately 170,000 abalone per year) and to expand its operation up to 500,000 abalone at • full build out. -

Coastal Dunes

BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES OF THE DEL MONTE FOREST COASTAL DUNES DEL MONTE FOREST PRESERVATION AND DEVELOPMENT PLAN Prepared for: Pebble Beach Company Post Office Box 1767 Pebble Beach, California 93953-1767 Contact: Mark Stilwell (831) 625-8497 Prepared by: Zander Associates 150 Ford Way, Suite 101 Novato, California 94945 Contact: Michael Zander July 2001 Zander Associates TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures and Plates 1.0 Introduction .................................................................................................................1 2.0 Overview of Dunes within the DMF Planning Area...................................................2 2.1 Remnant Dunes .......................................................................................................2 2.2 Rehabilitation Area..................................................................................................4 2.3 ESHA Boundary......................................................................................................6 3.0 Relationship to the DMF Plan .....................................................................................8 3.1 Preserve Areas (Area L and Signal Hill Dune) .......................................................8 3.2 Development Areas (New Golf Course and Facilities—Areas M & N).................8 3.2.1 General Design Considerations .......................................................................8 3.2.2 Golf Course Specific Design...........................................................................9 3.2.3 Golf -

Springs of California

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, DIBECTOB WATER- SUPPLY PAPER 338 SPRINGS OF CALIFORNIA BY GEKALD A. WARING WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1915 CONTENTS. Page. lntroduction by W. C. Mendenhall ... .. ................................... 5 Physical features of California ...... ....... .. .. ... .. ....... .............. 7 Natural divisions ................... ... .. ........................... 7 Coast Ranges ..................................... ....•.......... _._._ 7 11 ~~:~~::!:: :~~e:_-_-_·.-.·.·: ~::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: ::::: ::: 12 Sierra Nevada .................... .................................... 12 Southeastern desert ......................... ............. .. ..... ... 13 Faults ..... ....... ... ................ ·.. : ..... ................ ..... 14 Natural waters ................................ _.......................... 15 Use of terms "mineral water" and ''pure water" ............... : .·...... 15 ,,uneral analysis of water ................................ .. ... ........ 15 Source and amount of substances in water ................. ............. 17 Degree of concentration of natural waters ........................ ..· .... 21 Properties of mineral waters . ................... ...... _. _.. .. _... _....• 22 Temperature of natural waters ... : ....................... _.. _..... .... : . 24 Classification of mineral waters ............ .......... .. .. _. .. _......... _ 25 Therapeutic value of waters .................................... ... ... 26 Analyses -

Here's Why Pebble Beach Resorts Is So Much More Than Golf

Your legendary meeting. Our legendary setting. HERE’S WHY PEBBLE BEACH RESORTS IS SO MUCH MORE THAN GOLF © 2015 Pebble Beach Company. © 2015 Pebble PEBBLE BEACH Your legendary meeting. Our legendary setting. HERE’S WHY PEBBLE BEACH RESORTS IS SO MUCH MORE THAN GOLF By: Creighton Casper, Master Connection Associates & Tim Ryan, Pebble Beach Company TABLE OF CONTENTS America’s Course 3 The Allure of Pebble Beach 3 Corporate Meeting Destination 4 Marketing Paradox 4 Incomparable Location 5 Road Trip–Pacific Coast Highway 5 On Pebble Beach 6-10 The Pebble Beach Advantage 11 Productive Partnership 12 Pebble Beach Meetings • (800) 877-8991 • www.PebbleBeachMeetings.com • Page 2 AMERICA’S COURSE Since Pebble Beach Golf Links opened in 1919, Pebble Beach Resorts has become an international icon in the world of championship golf and a bucket list destination for serious golfers everywhere. Set along the rugged Pacific Coast of the Monterey Peninsula, the golf courses at Pebble Beach occupy some of the most beautiful and scenic spaces in California. For nearly 100 years, Pebble Beach has hosted the greats of the game and built an unequaled position in the storied history of golf. Famed Pebble Beach Golf Links has been called “The St. Andrews of the United States” and “America’s Course”. Each year, golfers from around the world make their way to the Monterey Peninsula to test their game on the fabled fairways and greens of the resort’s four championship courses. For many, this trip realizes the dream of a lifetime. Playing the storied tracks at Pebble Beach is a defining moment for golfers of all stripes and a cherished memory for those fortunate enough to experience it. -

The Carmel Pine Cone

VolumeThe 105 No. 42 Carmelwww.carmelpinecone.com Pine ConeOctober 18-24, 2019 T RUS T ED BY LOCALS AND LOVED BY VISI T ORS SINCE 1 9 1 5 Deal pending for Esselen tribe to buy ranch Cal Am takeover By CHRIS COUNTS But the takeover is not a done deal yet, despite local media reports to the contrary, Peter Colby of the Western study to be IF ALL goes according to plan, it won’t be a Silicon Rivers Conservancy told The Pine Cone this week. His Valley executive or a land conservation group that soon group is brokering the deal between the current owner of takes ownership of a remote 1,200-acre ranch in Big Sur the ranch, the Adler family of Sweden, and the Esselen released Nov. 6 but a Native American tribe with deep local roots. Tribe of Monterey County. “A contract for the sale is in place, By KELLY NIX but a number of steps need to be com- pleted first before the land is trans- THE LONG-AWAITED findings of a study to deter- ferred,” Colby said. mine the feasibility of taking over California American While Colby didn’t say how much Water’s local system and turning it into a government-run the land is selling for, it was listed operation will be released Nov. 6, the Monterey Peninsula at $8 million when The Pine Cone Water Management District announced this week. reported about it in 2017. But ear- The analysis was launched after voters in November lier this month, the California Nat- 2018 OK’d a ballot measure calling for the water district ural Resources Agency announced to use eminent domain, if necessary, to acquire Cal Am’s that something called “the Esselen Monterey Peninsula water system if the move was found Tribal Lands Conservation Project” to be cost effective. -

1968 General Plan

I I I I I I MONTEREY COUNTY GENERAL PLAN I MONTEREY COUNTY, STATE OF CALIFORNIA I I I I ADOPTED BY THE MONTEREY COUNTY PLANNING COMMISSION JULY 10, 1968 I ADOPTED BY THE BOARD OF SUPERVISORS OF MONTEREY COUNTY OCTOBER 22, 1968 I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I 0 N I I I MONTEREY COUNTY I I I I I I PREFACE I The Monterey County General Plan is an attempt to establish a county philosophy based on the values and desires of the people. This in turn becomes a valid basis for decisions by public bodies as well as private enterprise. Such a pro cedure is vitally needed in our rapidly changing environment. The General Plan I is a study of the ever changing pattern of Monterey County --a mirror in which to review the past, to comprehend the present, and to contemplate the future, This plan reflects years of research and study as well as many other reports such as I the continuing Facts and Figures, Recreation in Monterey County, Beach Acqui sition, and other plans which are shown as separate documents h~cause of the volume of material. I The size of Monterey County, its variety of climate, vegetation, and land forms make it imperative that only large land uses or broad proposals be used to portray geographically the objectives desired for the future development of the County. I Accordingly, in addition to the maps, greater emphasis in the General Plan is placed on the text which conveys in words the objectives as well as the princi ples and standards recommended to make them effective. -

The Quarterdeck / 1993-05-13

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Institutional Publications The Quarterdeck (publication) 1993-05-13 The Quarterdeck / 1993-05-13 Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey Callifornia http://hdl.handle.net/10945/52064 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL• Monterey, California ARMED ~ORCES DAY 'SATURDAY; MAY 15 IN THIS ISSUE: .. • ·-· ~ Employee awards ' :·: * ·MOARS course · !!~llii!!lll~11!J!!i!lii!l!:i!iii!if~!:!!i~!!i~lfl!!illl NAVY FLYING CLUB $18. Planes are checked out only to members who have a valid pilot' s license HOSTS 'OPEN HOUSE' and rental fees are charged for the planes. The new address for the club is 806 The Monterey Navy Hying Qub duty and retired military, DOD employ Airport Road. There is a secured access hosts an ''Open House" tomorrow, from ees and dependents. The members pay an gate into the airport. For more details and 1:30 - 4 p.m., at the Monterey Peninsula initiation fee of $30 and monthly dues of call 372-7033. Airport to conunemorate the opening of its newly constructed hangar. The club recently relocated to the :M©NTEREY>YMCA HONORs ·: sERVIGES north-east side of the airport and its new $55,000 facility. The new hangar, paid auR1NG ARMEo .. FoRces·wEEKf ·· MA v~ -1 :=g ··::: for by the flying club, provides more ·. Th~ YrttCA of' the M~n~~y Peninsula ~s~orting th/ liandicapped ai the room than the old facilities. Fuel costs honoftd five area service members dur- _,. Monterey County Fairgrounds; working will drop with the opening of the new irig their Military Appredatlon Awai-els > fo~ S«uriiJ and iDrormation ~nee hangar. -

Big Sur for Other Uses, See Big Sur (Disambiguation)

www.caseylucius.com [email protected] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Main_Page Big Sur For other uses, see Big Sur (disambiguation). Big Sur is a lightly populated region of the Central Coast of California where the Santa Lucia Mountains rise abruptly from the Pacific Ocean. Although it has no specific boundaries, many definitions of the area include the 90 miles (140 km) of coastline from the Carmel River in Monterey County south to the San Carpoforo Creek in San Luis Obispo County,[1][2] and extend about 20 miles (30 km) inland to the eastern foothills of the Santa Lucias. Other sources limit the eastern border to the coastal flanks of these mountains, only 3 to 12 miles (5 to 19 km) inland. Another practical definition of the region is the segment of California State Route 1 from Carmel south to San Simeon. The northern end of Big Sur is about 120 miles (190 km) south of San Francisco, and the southern end is approximately 245 miles (394 km) northwest of Los Angeles. The name "Big Sur" is derived from the original Spanish-language "el sur grande", meaning "the big south", or from "el país grande del sur", "the big country of the south". This name refers to its location south of the city of Monterey.[3] The terrain offers stunning views, making Big Sur a popular tourist destination. Big Sur's Cone Peak is the highest coastal mountain in the contiguous 48 states, ascending nearly a mile (5,155 feet/1571 m) above sea level, only 3 miles (5 km) from the ocean.[4] The name Big Sur can also specifically refer to any of the small settlements in the region, including Posts, Lucia and Gorda; mail sent to most areas within the region must be addressed "Big Sur".[5] It also holds thousands of marathons each year. -

Discover California State Parks in the Monterey Area

Crashing waves, redwoods and historic sites Discover California State Parks in the Monterey Area Some of the most beautiful sights in California can be found in Monterey area California State Parks. Rocky cliffs, crashing waves, redwood trees, and historic sites are within an easy drive of each other. "When you look at the diversity of state parks within the Monterey District area, you begin to realize that there is something for everyone - recreational activities, scenic beauty, natural and cultural history sites, and educational programs,” said Dave Schaechtele, State Parks Monterey District Public Information Officer. “There are great places to have fun with families and friends, and peaceful and inspirational settings that are sure to bring out the poet, writer, photographer, or artist in you. Some people return to their favorite state parks, year-after-year, while others venture out and discover some new and wonderful places that are then added to their 'favorites' list." State Parks in the area include: Limekiln State Park, 54 miles south of Carmel off Highway One and two miles south of the town of Lucia, features vistas of the Big Sur coast, redwoods, and the remains of historic limekilns. The Rockland Lime and Lumber Company built these rock and steel furnaces in 1887 to cook the limestone mined from the canyon walls. The 711-acre park allows visitors an opportunity to enjoy the atmosphere of Big Sur’s southern coast. The park has the only safe access to the shoreline along this section of cast. For reservations at the park’s 36 campsites, call ReserveAmerica at (800) 444- PARK (7275). -

The Discovery of an Isolated Anchor in Monterey, California Is Puzzling Because It Is Made Entirely of Bronze

THE MYSTERY OF BRONZE ANCHORS: THE MONTEREY BRONZE ANCHOR AS A CASE STUDY JEFFREY R. DELSESCAUX CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION, STOCKTON, CALIFORNIA The discovery of an isolated anchor in Monterey, California is puzzling because it is made entirely of bronze. Throughout history, iron and stone have been the typical material used in the manufacturing of ship anchors. The anchor was discovered in Monterey Bay, California in 1944 after becoming fouled in the anchor line of an oil tanker. Now permanently displayed outside the historic Customs House in Monterey State Historic Park, this bronze anchor continues to puzzle researchers. This paper will discuss the possible sources of the Monterey bronze anchor and hypothesize on geographical pressures and lack of industrial resources that could have produced a need for bronze anchors. Iron anchors are a common artifact type displayed in the various seaports around the world. They are so common that most people give them little attention. These anchors usually lack provenience and are in poor condition from their exposure to salt water and, having never been conserved after being recovered, they are deteriorating. It is disappointing because although they lack provenience, anchors can still provide useful data. Typology can provided details, such as age and nationality, and provide clues into the past trading patterns of seaports. The study of anchors might be neglected, but there is one anchor that deserves closer inspection. At Monterey State Historic Park (SHP) in Monterey, California, an unusual bronze anchor lies outside the Customs House, a historic structure that dates back to 1827 (Figure 1). A plaque placed next to it reads, "Old bronze anchor brought up from the bottom of Monterey Bay in July 1944. -

2.06 AT&T Pebble Beach

Tournament Fact Sheet AT&T Pebble Beach Pro-Am Pebble Beach Golf Links • Pebble Beach, Calif. • Feb. 6-9, 2020 Director of Golf Course Maintenance Tournament Set-up Chris Dalhamer, CGCS Par: 72 Phone: 831-622-6601 Yardage: 6,816 Email: [email protected] Stimpmeter: 10.5 Years as GCSAA Member: 20 Course Statistics Years at Pebble Beach: 9 Average Green Size: 3,500 sq. ft. Average Tee Size: 3,500 sq. ft. Previous Courses: Spyglass (super), Carmel Valley Ranch Acres of Fairway: 30 (dir. of maint.), Pebble Beach (assistant) Acres of Rough: 80 Hometown: Pacific Grove, Calif. Number of Sand Bunkers: 118 Education: CS-Chico and Monterey Peninsula College Number of Water Hazards: Pacific Ocean Soil Conditions: Sandy loam Number of Employees: 30 Water Sources: Effluent water Number of Tournament Volunteers: 15-20 Drainage Conditions: Fair Other Key Golf Personnel Turfgrass Eric McAlister, Assistant Superintendent Greens: Poa annua .125” Bubba Wright, Assistant Superintendent Tees: Ryegrass .400” Mark Thomas, Irrigation Technician Fairways: Poa annua .450” Charlie Almony, Field Supervisor Rough: Ryegrass 2” Jon Rybicki, Equipment Manager John Swain, Club president/manager Additional Notes Eric Lippert, PGA Professional • There was 10 inches of rainfall from Nov. John Sawin, director of Golf 25-Dec. 31 and has made the course wetter than normal. Course Architect • An improved short course designed by Architect (year): Jack Nevill and Douglas Grant (1919) Tiger Woods will open this year. Course Owner: Lone Cypress Group Rounds Per Year: 60,000 • Species of trees on course include Monterey pines, coastal live oaks and Monterey cypress Tournament Fact Sheets for the PGA, LPGA, Champions and Korn Ferry Tours can be found all year at: • Pebble Beach is Audubon certified.