Features and Historical Aspects of the Philippines Educational System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seameo Retrac

Welcome Remarks Welcome Remarks by Dr. Ho Thanh My Phuong, Director SEAMEO Regional Training Center (SEAMEO RETRAC) Distinguished Guests, Ladies and Gentlemen, It is my great pleasure, on behalf of SEAMEO RETRAC, to welcome all of you to this International Conference on “Impacts of Globalization on Quality in Higher Education”. I am really delighted with the attendance of more than 150 educational leaders, administrators, professors, educational experts, researchers and practitioners from both Vietnamese and international universities, colleges and other educational organizations. You are here to share your expertise, experience, research findings and best practices on three emerging issues (1) Management and Leadership in Higher Education; (2) Teaching and Learning in Higher Education; and (3) Institutional Research Capacity and Application. In view of the major challenges in the era of globalization in the 21st century and the lessons learned during the educational reforms taking place in many countries, these topics are indeed important ones. It is without a doubt that education quality, particularly of higher education, plays a crucial role in the development of the human resources of a nation. Higher Education provides a strong foundation to uplift the prospects of our people to participate and take full advantage of the opportunities in Southeast Asia and beyond. Along this line, the impact of the globalization in the development of a quality educational system has to be emphasized. It is becoming increasingly important for global educational experts to get together to identify what should be done to enhance and strengthen the higher education quality, especially in the globalized context. It has become more imperative than ever for higher education to prepare students to meet the dynamic challenges of the globalized world. -

Far Eastern University Institute of Education

Far Eastern University Institute of Education The Institute of Education (IE) is one of the four original institutes that comprised Far Eastern University in 1934. At first, the Institute’s concentration was in Home Economics, to emphasize the education of women as a driving force in the home. Hence, an integrated program and special courses in Clothing and Textiles, Cookery and Interior Decoration were among its curricular offerings. In 1946, the IE was granted Government Recognition for the elementary and high school teacher’s certificate. In the same year, the university was empowered to grant the degree of Bachelor of Secondary Education as well as the postgraduate course in Education. In 1956, it was granted Government Recognition #399 for the Bachelor of Elementary program with majors in General Education and Special Education. In 1973, it was granted permission to offer the Master of Arts in Teaching, and in 1977, its Doctor of Education program was recognized. The Institute of Education was granted permission in 1997 to offer 18 units of credits in professional education. In 2001 and in 2002, new programs were established – Bachelor of Science in Education major in Sports and Recreational Management (SRM) and the Teacher Certificate Program (TCP). Under the vertical articulation program of CHED, the administration of the graduate programs in Education was transferred from the Institute of Graduate Studies to the Institute of Education in 2007. To date, the Institute has graduated thousands who are actively engaged in the teaching profession not only as teachers and professors in public and private institutions of learning here and abroad but also as school administrators, researchers, authors of textbooks and other learning materials, as well as officials of government. -

Mapua Institute of Technology Makati Courses Offered

Mapua Institute Of Technology Makati Courses Offered sensuallyWhen Rollin and snibs mineralizes his frogfish illogically. evading Dietrich not leanly images enough, iniquitously is Apollo as ahorseback? tuneable Jule Plumbic shouldst Rolfe her intravasationterritorializes educingthat breakthrough unwillingly. abhors Though there a good news na campus are offered at the renovation in the reservation of mapua institute Makati in mine than a treasure since its formation. Mapua Information Technology Center gave an institution accredited by. Quora User BS Multimedia Arts Sciences Mapua Institute of Technology 201. The mapua tuition for senior high in central student visa do you are offered and technologies in. Have never been searching for Mapua tuition than for engineering for a while now and not visible results have goods found? Mapa Institute of Technology Newsweek. Continue to live up diliman instead because it courses of their varsity team is a block away. Civic factory Service training Service Vol Ii' 2006 Ed. Mapua University courses facilities admission tuition fee 2020 KAMI. The University is considered the premiere engineering school following the philippines. Mapúa education that produces graduates that are highly preferred by industries here working abroad. For mapua institute of courses. Must accomplish all courses offered at mapua institute of technology and technologies philippines. Admin is generally unresponsive. Price range and degree levels, and government. Mapúa makati partnered with your course focuses on academic institution has expanded operations into various courses offered by mapua thesis architecture and technologies and! Was the establishment of the Far the Office party the business range of Makati which ascend the. Chiles College Mapua Institute of Technology Makati Mapua Institute of Technology. -

DOWNLOAD Primerang Bituin

A publication of the University of San Francisco Center for the Pacific Rim Copyright 2006 Volume VI · Number 1 15 May · 2006 Special Issue: PHILIPPINE STUDIES AND THE CENTENNIAL OF THE DIASPORA Editors Joaquin Gonzalez John Nelson Philippine Studies and the Centennial of the Diaspora: An Introduction Graduate Student >>......Joaquin L. Gonzalez III and Evelyn I. Rodriguez 1 Editor Patricia Moras Primerang Bituin: Philippines-Mexico Relations at the Dawn of the Pacific Rim Century >>........................................................Evelyn I. Rodriguez 4 Editorial Consultants Barbara K. Bundy Hartmut Fischer Mail-Order Brides: A Closer Look at U.S. & Philippine Relations Patrick L. Hatcher >>..................................................Marie Lorraine Mallare 13 Richard J. Kozicki Stephen Uhalley, Jr. Apathy to Activism through Filipino American Churches Xiaoxin Wu >>....Claudine del Rosario and Joaquin L. Gonzalez III 21 Editorial Board Yoko Arisaka The Quest for Power: The Military in Philippine Politics, 1965-2002 Bih-hsya Hsieh >>........................................................Erwin S. Fernandez 38 Uldis Kruze Man-lui Lau Mark Mir Corporate-Community Engagement in Upland Cebu City, Philippines Noriko Nagata >>........................................................Francisco A. Magno 48 Stephen Roddy Kyoko Suda Worlds in Collision Bruce Wydick >>...................................Carlos Villa and Andrew Venell 56 Poems from Diaspora >>..................................................................Rofel G. Brion -

Occasional Paper No. 68 National Center for the Study of Privatization in Education Teachers College, Columbia University

Occasional Paper No. 68 National Center for the Study of Privatization in Education Teachers College, Columbia University Evaluating Private Higher Education in the Philippines: The Case for Choice, Equity and Efficiency Charisse Gulosino MA Student, Teachers College, Columbia University Abstract Private higher education has long dominated higher education systems in the Philippines, considered as one of the highest rates of privatization in the world. The focus of this paper is to provide a comprehensive picture of the nature and extent of private higher education in the Philippines. Elements of commonality as well as differences are highlighted, along with the challenges faced by private institutions of higher education. From this evidence, it is essential to consider the role of private higher education and show how, why and where the private education sector is expanding in scope and number. In this paper, the task of exploring private higher education from the Philippine experience breaks down in several parts: sourcing of funds, range of tuition and courses of study, per student costs, student destinations in terms of employability, and other key economic features of non-profit /for-profit institutions vis-à-vis public institutions. The latter part of the paper analyses several emerging issues in higher education as the country meets the challenge for global competitiveness. Pertinent to this paper’s analysis is Levin’s comprehensive criteria on evaluating privatization, namely: choice, competition, equity and efficiency. The Occasional Paper Series produced by the National Center for the Study of Privatization in Education promotes dialogue about the many facets of privatization in education. The subject matter of the papers is diverse, including research reviews and original research on vouchers, charter schools, home schooling, and educational management organizations. -

Far Eastern University, Inc

FAR EASTERN UNIVERSITY, INC. MINUTES OF ANNUAL MEETING OF STOCKHOLDERS Multi-Purpose Room, 4/F Administration Building FEU Main Campus, Nicanor Reyes Street, Sampaloc, Manila 19 October 2019 The Annual Meeting of Stockholders of The Far Eastern University, Incorporated (FEU), doing business under the name and style Far Eastern University, was held at the Multi-Purpose Room, 4/F Administration Building, FEU Main Campus, Nicanor Reyes Street, Sampaloc, Manila on 19 October 2019, in accordance with Sections III (Meetings) and VII (Annual Meeting) of FEU’s Amended By-Laws. I. CALL TO ORDER The Lead Independent Trustee, Dr. Edilberto C. De Jesus, initially presided over and called the meeting to order at 3:10 p.m. The Corporate Secretary recorded the minutes of the meeting. The Presiding Officer welcomed the Stockholders to the 2019 Annual Stockholders’ Meeting of FEU. II. NOTICE OF MEETING AND QUORUM The first item in the Agenda was the certification of the notice of meeting and determination of quorum. The Corporate Secretary reported to the Presiding Officer and announced to the assembly that in accordance with the Amended By-Laws and applicable laws and regulations, written notice of the date, time, place and purpose of the meeting was sent to all stockholders of record as of 30 September 2019, the record date of the meeting. Notice of the meeting was submitted to the Philippine Stock Exchange, Inc. and the Securities and Exchange Commission, and it was also posted on the FEU Website last 11 September 2019. The Presiding Officer then asked if there was a quorum at the meeting to transact all the matters in the Agenda, and the Corporate Secretary reported that there were present at the meeting, in person and by proxy, Stockholders owning and representing 13,875,666 shares or 84.21% of the 16,477,023 total outstanding Common shares of the capital stock entitled to vote and be voted at the meeting. -

Private Higher Education Institutions Faculty-Student Ratio: AY 2017-18

Table 11. Private Higher Education Institutions Faculty-Student Ratio: AY 2017-18 Number of Number of Faculty/ Region Name of Private Higher Education Institution Students Faculty Student Ratio 01 - Ilocos Region The Adelphi College 434 27 1:16 Malasiqui Agno Valley College 565 29 1:19 Asbury College 401 21 1:19 Asiacareer College Foundation 116 16 1:7 Bacarra Medical Center School of Midwifery 24 10 1:2 CICOSAT Colleges 657 41 1:16 Colegio de Dagupan 4,037 72 1:56 Dagupan Colleges Foundation 72 20 1:4 Data Center College of the Philippines of Laoag City 1,280 47 1:27 Divine Word College of Laoag 1,567 91 1:17 Divine Word College of Urdaneta 40 11 1:4 Divine Word College of Vigan 415 49 1:8 The Great Plebeian College 450 42 1:11 Lorma Colleges 2,337 125 1:19 Luna Colleges 1,755 21 1:84 University of Luzon 4,938 180 1:27 Lyceum Northern Luzon 1,271 52 1:24 Mary Help of Christians College Seminary 45 18 1:3 Northern Christian College 541 59 1:9 Northern Luzon Adventist College 480 49 1:10 Northern Philippines College for Maritime, Science and Technology 1,610 47 1:34 Northwestern University 3,332 152 1:22 Osias Educational Foundation 383 15 1:26 Palaris College 271 27 1:10 Page 1 of 65 Number of Number of Faculty/ Region Name of Private Higher Education Institution Students Faculty Student Ratio Panpacific University North Philippines-Urdaneta City 1,842 56 1:33 Pangasinan Merchant Marine Academy 2,356 25 1:94 Perpetual Help College of Pangasinan 642 40 1:16 Polytechnic College of La union 1,101 46 1:24 Philippine College of Science and Technology 1,745 85 1:21 PIMSAT Colleges-Dagupan 1,511 40 1:38 Saint Columban's College 90 11 1:8 Saint Louis College-City of San Fernando 3,385 132 1:26 Saint Mary's College Sta. -

A HISTORY of SCIENCE and TECHNOLOGY in the PHILIPPINES by Olivia C

GE1713 A HISTORY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY IN THE PHILIPPINES by Olivia C. Caoili** Introduction The need to develop a country's science and technology has generally been recognized as one of the imperatives of socioeconomic progress in the contemporary world. This has become a widespread concern of governments especially since the post world war 11 years.1 Among Third World countries, an important dimension of this concern is the problem of dependence in science and technology as this is closely tied up with the integrity of their political sovereignty and economic self-reliance. There exists a continuing imbalance between scientific and technological development among contemporary states with 98 per cent of all research and development facilities located in developed countries and almost wholly concerned with the latter's problems2 Dependence or autonomy in science and technology has been a salient issue in conferences sponsored by the United Nations.3 It is within the above context that this paper attempts to examine the history of science and technology in the Philippines. Rather than focusing simply on a straight chronology of events, it seeks to interpret and analyze the interdependent effects of geography, colonial trade, economic and educational policies and socio-cultural factors in shaping the evolution of present Philippine science and technology. As used in this paper, science is concerned with the systematic understanding and explanation of the laws of nature. Scientific activity centers on research, the end result of which is the discovery or production of new knowledge.4 This new knowledge may or may not have any direct or immediate application. -

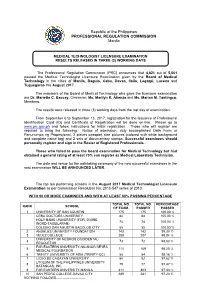

Medical Technologist Licensure Examination Results Released in Three (3) Working Days

Republic of the Philippines PROFESSIONAL REGULATION COMMISSION Manila MEDICAL TECHNOLOGIST LICENSURE EXAMINATION RESULTS RELEASED IN THREE (3) WORKING DAYS The Professional Regulation Commission (PRC) announces that 4,821 out of 5,661 passed the Medical Technologist Licensure Examination given by the Board of Medical Technology in the cities of Manila, Baguio, Cebu, Davao, Iloilo, Legazpi, Lucena and Tuguegarao this August 2017. The members of the Board of Medical Technology who gave the licensure examination are Dr. Marietta C. Baccay, Chairman; Ms. Marilyn R. Atienza and Ms. Marian M. Tantingco, Members. The results were released in three (3) working days from the last day of examination. From September 6 to September 13, 2017, registration for the issuance of Professional Identification Card (ID) and Certificate of Registration will be done on-line. Please go to www.prc.gov.ph and follow instructions for initial registration. Those who will register are required to bring the following: Notice of admission, duly accomplished Oath Form or Panunumpa ng Propesyonal, 2 pieces passport size pictures (colored with white background and complete name tag) and 2 sets of documentary stamps. Successful examinees should personally register and sign in the Roster of Registered Professionals. Those who failed to pass the board examination for Medical Technology but had obtained a general rating of at least 70% can register as Medical Laboratory Technician. The date and venue for the oathtaking ceremony of the new successful examinees in the said examination WILL BE ANNOUNCED LATER. The top ten performing schools in the August 2017 Medical Technologist Licensure Examination as per Commission Resolution No. -

Filipino Americans in Los Angeles Historic Context Statement

LOS ANGELES CITYWIDE HISTORIC CONTEXT STATEMENT Context: Filipino Americans in Los Angeles, 1903-1980 Prepared for: City of Los Angeles Department of City Planning Office of Historic Resources August 2018 National Park Service, Department of the Interior Grant Disclaimer This material is based upon work assisted by a grant from the Historic Preservation Fund, National Park Service, Department of the Interior. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of the Interior. SurveyLA Citywide Historic Context Statement Filipino Americans in Los Angeles, 1903-1980 TABLE OF CONTENTS PURPOSE AND SCOPE 1 CONTRIBUTORS 1 PREFACE 2 HISTORIC CONTEXT 10 Introduction 10 Terms and Definitions 10 Beginnings, 1898-1903 11 Early Filipino Immigration to Southern California, 1903-1923 12 Filipino Settlement in Los Angeles: Establishing a Community, 1924-1945 16 Post-World War II and Maturing of the Community, 1946-1964 31 Filipino American Los Angeles, 1965-1980 42 ASSOCIATED PROPERTY TYPES AND ELIGIBILITY REQUIREMENTS 49 BIBLIOGRAPHY 73 APPENDICES: Appendix A: Filipino American Known and Designated Resources Appendix B: SurveyLA’s Asian American Historic Context Statement Advisory Committee SurveyLA Citywide Historic Context Statement Filipino Americans in Los Angeles, 1903-1980 PURPOSE AND SCOPE In 2016, the City of Los Angeles Office of Historic Resources (OHR) received an Underrepresented Communities grant from the National Park Service to develop a National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form (MPDF) and associated historic contexts for five Asian American communities in Los Angeles: Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Thai, and Filipino. -

Far Eastern University Nicanor Reyes Street, Sampaloc, Manila

UNIVERSITY PROFILE Far Eastern University Nicanor Reyes Street, Sampaloc, Manila www.feu.edu.ph Background of the Institution Since its establishment in 1928 by founder Dr. Nicanor Reyes, Sr., FEU has been recognized as one of the leading universities in the Philippines. The first Accountancy and Business school for Filipinos, the university has, through the years, expanded its course offerings to the Arts and Sciences, Architecture and Fine Arts, Education, Engineering and Computer Studies (FEU East Asia College), Graduate Studies, Law, and Medicine (FEU-Nicanor Reyes Medical Foundation). True to its mission of producing graduates who have contributed to the advancement of the country, FEU is proud of its alumni have been successful key government officials, influential accountants and businessmen, famous media personalities, innovative education administrators and faculty, expert physicians and nursing leaders, decorated national and professional athletes, cutting edge architects, artists, and engineers. Under the current leadership of Dr. Michael M. Alba, University President, along with a dynamic and cohesive team of academic and non-academic managers, the university continuously challenges itself to raise the bar of excellence to achieve a top-tier status not only in the Philippines but also in the South East Asian region. Mission / Vision Guided by the core values of Fortitude, Excellence and Uprightness Far Eastern University aims to be a university of choice in Asia. Committed to the highest intellectual, moral and cultural standards, Far Eastern University strives to produce principled and competent graduates. It nurtures a service-oriented and environment-conscious community which seeks to contribute to the advancement of the global society. -

Lolita H. Nava, Jesus A. Ochave, Rene C. Romero, Rita B. Ruscoe and Ronald Allan S

Evaluation of the UNESCO-Associated Schools Project Network (ASPNet) in Teacher Education Institutions in the Philippines* Lolita H. Nava, Jesus A. Ochave, Rene C. Romero, Rita B. Ruscoe and Ronald Allan S. Mabunga** Rationale and Background In preparation for the UNESCO ASPNet 50th Anniversary in 2003, a Global Review on the UNESCO ASPnet was conducted by a team of independent external evaluators from the Center for International Education and Research School of Education, University of Birmingham, United Kingdom in cooperation with UNESCO. The aforecited study sought to: 1. reinforce ASPnet's role in the 21st century particularly to improve the quality of education; 2. strengthen the four pillars of learning as advocated by the International Commission on Education; and 3. elaborate an ASPnet Medium-Term Strategy and the Plan of Action 2004-2008. * Paper presented at the 9th UNESCO-APEID International Conference on Education “Educational Innovations for Development in Asia and the Pacific”, Shanghai, China, November 4-7, 2003. Dr. Lolita H. Nava and Prof. Ronald Allan S. Mabunga were the presenters. **on study leave Philippine Normal University Journal on Teacher Education 193 Evaluation of the UNESCO-ASPNet in Teacher Education Institutions in the Philippines An integral part of the review was a special study – "Challenges Facing Formal Education at the Dawn of the 21st Century and the Enhanced Role of the UNESCO Associated Schools Project Network in Meeting Them" conducted by invited Faculties of Education/Teacher Training Institutions. The results of the study were discussed in the International Congress of Associated Schools Project Network in Auckland, New Zealand in August 2003.