Madama Butterfly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JORDAN This Publication Has Been Produced with the Financial Assistance of the European Union Under the ENI CBC Mediterranean

ATTRACTIONS, INVENTORY AND MAPPING FOR ADVENTURE TOURISM JORDAN This publication has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union under the ENI CBC Mediterranean Sea Basin Programme. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of the Official Chamber of Commerce, Industry, Services and Navigation of Barcelona and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union or the Programme management structures. The European Union is made up of 28 Member States who have decided to gradually link together their know-how, resources and destinies. Together, during a period of enlargement of 50 years, they have built a zone of stability, democracy and sustainable development whilst maintaining cultural diversity, tolerance and individual freedoms. The European Union is committed to sharing its achievements and its values with countries and peoples beyond its borders. The 2014-2020 ENI CBC Mediterranean Sea Basin Programme is a multilateral Cross-Border Cooperation (CBC) initiative funded by the European Neighbourhood Instrument (ENI). The Programme objective is to foster fair, equitable and sustainable economic, social and territorial development, which may advance cross-border integration and valorise participating countries’ territories and values. The following 13 countries participate in the Programme: Cyprus, Egypt, France, Greece, Israel, Italy, Jordan, Lebanon, Malta, Palestine, Portugal, Spain, Tunisia. The Managing Authority (JMA) is the Autonomous Region of Sardinia (Italy). Official Programme languages are Arabic, English and French. For more information, please visit: www.enicbcmed.eu MEDUSA project has a budget of 3.3 million euros, being 2.9 million euros the European Union contribution (90%). -

Mtv and Transatlantic Cold War Music Videos

102 MTV AND TRANSATLANTIC COLD WAR MUSIC VIDEOS WILLIAM M. KNOBLAUCH INTRODUCTION In 1986 Music Television (MTV) premiered “Peace Sells”, the latest video from American metal band Megadeth. In many ways, “Peace Sells” was a standard pro- motional video, full of lip-synching and head-banging. Yet the “Peace Sells” video had political overtones. It featured footage of protestors and police in riot gear; at one point, the camera draws back to reveal a teenager watching “Peace Sells” on MTV. His father enters the room, grabs the remote and exclaims “What is this garbage you’re watching? I want to watch the news.” He changes the channel to footage of U.S. President Ronald Reagan at the 1986 nuclear arms control summit in Reykjavik, Iceland. The son, perturbed, turns to his father, replies “this is the news,” and lips the channel back. Megadeth’s song accelerates, and the video re- turns to riot footage. The song ends by repeatedly asking, “Peace sells, but who’s buying?” It was a prescient question during a 1980s in which Cold War militarism and the nuclear arms race escalated to dangerous new highs.1 In the 1980s, MTV elevated music videos to a new cultural prominence. Of course, most music videos were not political.2 Yet, as “Peace Sells” suggests, dur- ing the 1980s—the decade of Reagan’s “Star Wars” program, the Soviet war in Afghanistan, and a robust nuclear arms race—music videos had the potential to relect political concerns. MTV’s founders, however, were so culturally conserva- tive that many were initially wary of playing African American artists; addition- ally, record labels were hesitant to put their top artists onto this new, risky chan- 1 American President Ronald Reagan had increased peace-time deicit defense spending substantially. -

Movie Store Collections- Includes Factory Download Service

Kaleidescape Movie Store Collections- Includes Factory Download Service. *Content Availability Subject to Change. Collection of 4K Ultra HD & 4K HDR Films Academy Award Winners- Best Picture Collection of Family Films Collection of Concerts Collection of Best Content from BBC Our Price $1,250* Our Price $1,450* Our Price $2,450* Our Price $625* Our Price $650* MSCOLL-UHD MSCOLL-BPW MSCOLL-FAM MSCOLL-CON MSCOLL-BBC 2001: A Space Odyssey 12 Years a Slave Abominable Adele: Live at the Royal Albert Hall Blue Planet II A Star Is Born A Beautiful Mind Aladdin Alicia Keys: VH1 Storytellers Doctor Who (Season 8) Alien A Man for All Seasons Alice in Wonderland Billy Joel: Live at Shea Stadium Doctor Who (Season 9) Apocalypse Now: Final Cut All About Eve April and the Extraordinary World Celine Dion: Taking Chances World Tour - The Concert Doctor Who (Season 10) Avengers: Endgame All Quiet on the Western Front Babe Eagles: Farewell 1 Tour — Live from Melbourne Doctor Who (Season 11) Avengers: Infinity War All the King's Men Back to the Future Elton John: The Million Dollar Piano Doctor Who Special 2012: The Snowmen Baby Driver Amadeus Back to the Future Part II Eric Clapton: Slowhand at 70 - Live at the Royal Albert Hall Doctor Who Special 2013: The Day of the Doctor Blade Runner 2049 American Beauty Back to the Future Part III Genesis: Three Sides Live Doctor Who Special 2013: The Time of the Doctor Blade Runner: The Final Cut An American in Paris Beauty and the Beast Hans Zimmer: Live in Prague Doctor Who Special 2014: Last Christmas Blue Planet II Annie Hall Cars INXS: Live Baby Live Doctor Who Special 2015: The Husbands of River Song Bohemian Rhapsody Argo Cars 2 Jackie Evancho: Dream with Me in Concert Doctor Who Special 2016: The Return of Doctor Mysterio Chinatown Around the World in 80 Days Cars 3 Jeff Beck: Performing This Week.. -

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood

THE MAGAZINE FOR FILM & TELEVISION EDITORS, ASSISTANTS & POST- PRODUCTION PROFESSIONALS THE SUMMER MOVIE ISSUE IN THIS ISSUE Once Upon a Time in Hollywood PLUS John Wick: Chapter 3 – Parabellum Rocketman Toy Story 4 AND MUCH MORE! US $8.95 / Canada $8.95 QTR 2 / 2019 / VOL 69 FOR YOUR EMMY ® CONSIDERATION OUTSTANDING SINGLE-CAMERA PICTURE EDITING FOR A DRAMA SERIES - STEVE SINGLETON FYC.NETFLIX.COM CINEMA EDITOR MAGAZINE COVER 2 ISSUE: SUMMER BLOCKBUSTERS EMMY NOMINATION ISSUE NETFLIX: BODYGUARD PUB DATE: 06/03/19 TRIM: 8.5” X 11” BLEED: 8.75” X 11.25” PETITION FOR EDITORS RECOGNITION he American Cinema Editors Board of Directors • Sundance Film Festival T has been actively pursuing film festivals and • Shanghai International Film Festival, China awards presentations, domestic and international, • San Sebastian Film Festival, Spain that do not currently recognize the category of Film • Byron Bay International Film Festival, Australia Editing. The Motion Picture Editors Guild has joined • New York Film Critics Circle with ACE in an unprecedented alliance to reach out • New York Film Critics Online to editors and industry people around the world. • National Society of Film Critics The organizations listed on the petition already We would like to thank the organizations that have recognize cinematography and/or production design recently added the Film Editing category to their Annual Awards: in their annual awards presentations. Given the essential role film editors play in the creative process • Durban International Film Festival, South Africa of making a film, acknowledging them is long • New Orleans Film Festival overdue. We would like to send that message in • Tribeca Film Festival solidarity. -

Newsletter • Bulletin

NATIONAL CAPITAL OPERA SOCIETY • SOCIETE D'OPERA DE LA CAPITALE NATIONALE Newsletter • Bulletin Summer 2000 L’Été A WINTER OPERA BREAK IN NEW YORK by Shelagh Williams The Sunday afternoon programme at Alice Tully Having seen their ads and talked to Helen Glover, their Hall was a remarkable collaboration of poetry and words new Ottawa representative, we were eager participants and music combining the poetry of Emily Dickinson in the February “Musical Treasures of New York” ar- recited by Julie Harris and seventeen songs by ten dif- ranged by Pro Musica Tours. ferent composers, sung by Renee Fleming. A lecture We left Ottawa early Saturday morning in our bright preceded the concert and it was followed by having most pink (and easily spotted!) 417 Line Bus and had a safe of the composers, including Andre Previn, join the per- and swift trip to the Belvedere Hotel on 48th St. Greeted formers on stage for the applause. An unusual and en- by Larry Edelson, owner/director and tour leader, we joyable afternoon. met our fellow opera-lovers (six from Ottawa, one from Monday evening was the Met’s block-buster pre- Toronto, five Americans and three ladies from Japan) at miere production of Lehar’s The Merry Widow, with a welcoming wine and cheese party. Frederica von Stade and Placido Domingo, under Sir Saturday evening the opera was Offenbach’s Tales Andrew Davis, in a new English translation. The oper- of Hoffmann. This was a lavish (though not new) pro- etta was, understandably, sold out, and so the only tick- duction with sumptuous costumes, sets descending to ets available were seats in the Family Circle (at the very reappear later, and magical special effects. -

Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation

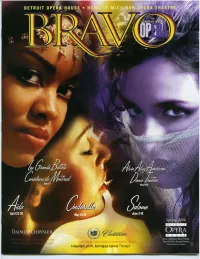

2006 Spring Opera Season is sponsored by Cadillac Copyright 2010, Michigan Opera Theatre LaSalle Bank salutes those who make the arts a part of our lives. Personal Banking· Commercial Banking· Wealth Management Making more possible LaSalle Bank ABN AMRO ~ www. la sal lebank.com t:.I Wealth Management is a division of LaSalle Bank, NA Copyright 2010,i'ENm Michigan © 2005 LaSalle Opera Bank NTheatre.A. Member FDIC. Equal Opportunity Lender. 2006 The Official MagaZine of the Detroit Opera House BRAVO IS A MICHI GAN OPERA THEAT RE P UB LI CATION Sprin",,---~ CONTRI BUTORS Dr. David DiChiera Karen VanderKloot DiChiera eason Roberto Mauro Michigan Opera Theatre Staff Dave Blackburn, Editor -wELCOME P UBLISHER Letter from Dr. D avid DiChiera ...... .. ..... ...... 4 Live Publishing Company Frank Cucciarre, Design and Art Direction ON STAGE Bli nk Concept &: Design, Inc. Production LES GRAND BALLETS CANADIENS de MONTREAL .. 7 Chuck Rosenberg, Copy Editor Be Moved! Differently . ............................... ... 8 Toby Faber, Director of Advertising Sales Physicians' service provided by Henry Ford AIDA ............... ..... ...... ... .. ... .. .... 11 Medical Center. Setting ................ .. .. .................. .... 12 Aida and the Detroit Opera House . ..... ... ... 14 Pepsi-Cola is the official soft drink and juice provider for the Detroit Opera House. C INDERELLA ...... ....... ... ......... ..... .... 15 Cadillac Coffee is the official coffee of the Detroit Setting . ......... ....... ....... ... .. .. 16 Opera House. Steinway is the official piano of the Detroit Opera ALVIN AILEY AMERICAN DANCE THEATER .. ..... 17 House and Michigan Opera Theatre. Steinway All About Ailey. 18 pianos are provided by Hammell Music, exclusive representative for Steinway and Sons in Michigan. SALOME ........ ... ......... .. ... ... 23 President Tuxedo is the official provider of Setting ............. .. ..... .......... ..... 24 formal wear for the Detroit Opera House. -

Michael Schade at a Special Release of His New Hyperion Recording “Of Ladies and Love...”

th La Scena Musicale cene English Canada Special Edition September - October 2002 Issue 01 Classical Music & Jazz Season Previews & Calendar Southern Ontario & Western Canada MichaelPerpetual Schade Motion Canada Post Publications Mail Sales Agreement n˚. 40025257 FREE TMS 1-01/colorpages 9/3/02 4:16 PM Page 2 Meet Michael Schade At a Special Release of his new Hyperion recording “Of ladies and love...” Thursday Sept.26 At L’Atelier Grigorian Toronto 70 Yorkville Ave. 5:30 - 7:30 pm Saturday Sept. 28 At L’Atelier Grigorian Oakville 210 Lakeshore Rd.E. 1:00 - 3:00 pm The World’s Finest Classical & Jazz Music Emporium L’Atelier Grigorian g Yorkville Avenue, U of T Bookstore, & Oakville GLENN GOULD A State of Wonder- The Complete Goldberg Variations (S3K 87703) The Goldberg Variations are Glenn Gould’s signature work. He recorded two versions of Bach’s great composition—once in 1955 and again in 1981. It is a testament to Gould’s genius that he could record the same piece of music twice—so differently, yet each version brilliant in its own way. Glenn Gould— A State Of Wonder brings together both of Gould’s legendary performances of The Goldberg Variations for the first time in a deluxe, digitally remastered, 3-CD set. Sony Classical celebrates the 70th anniversary of Glenn Gould's birth with a collection of limited edition CDs. This beautifully packaged collection contains the cornerstones of Gould’s career that marked him as a genius of our time. A supreme intrepreter of Bach, these recordings are an essential addition to every music collection. -

The Preludes in Chinese Style

The Preludes in Chinese Style: Three Selected Piano Preludes from Ding Shan-de, Chen Ming-zhi and Zhang Shuai to Exemplify the Varieties of Chinese Piano Preludes D.M.A. DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jingbei Li, D.M.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2019 D.M.A. Document Committee: Professor Steven M. Glaser, Advisor Dr. Arved Ashby Dr. Edward Bak Copyrighted by Jingbei Li, D.M.A 2019 ABSTRACT The piano was first introduced to China in the early part of the twentieth century. Perhaps as a result of this short history, European-derived styles and techniques influenced Chinese composers in developing their own compositional styles for the piano by combining European compositional forms and techniques with Chinese materials and approaches. In this document, my focus is on Chinese piano preludes and their development. Having performed the complete Debussy Preludes Book II on my final doctoral recital, I became interested in comprehensively exploring the genre for it has been utilized by many Chinese composers. This document will take a close look in the way that three modern Chinese composers have adapted their own compositional styles to the genre. Composers Ding Shan-de, Chen Ming-zhi, and Zhang Shuai, while prominent in their homeland, are relatively unknown outside China. The Three Piano Preludes by Ding Shan-de, The Piano Preludes and Fugues by Chen Ming-zhi and The Three Preludes for Piano by Zhang Shuai are three popular works which exhibit Chinese musical idioms and demonstrate the variety of approaches to the genre of the piano prelude bridging the twentieth century. -

ELTON JOHN THREE-YEAR FAREWELL YELLOW BRICK ROAD TOUR ADDS FINAL 2020 DATES in NORTH AMERICA Just Added Simmons Bank Arena* July 3, 2020

ELTON JOHN THREE-YEAR FAREWELL YELLOW BRICK ROAD TOUR ADDS FINAL 2020 DATES IN NORTH AMERICA Just Added Simmons Bank Arena* July 3, 2020 *formerly Verizon Arena American Express Pre-Sale begins Thursday, November 14 at 10am Public On Sale begins Friday, November 22 at 10am local time “..The Farewell Yellow Brick Road tour is the most bombastic, elaborate, high-tech arena show he’s ever attempted.” – Rolling Stone Photo Credit: Ben Gibson, © HST Global Limited, courtesy of Rocket Entertainment New York, NY - November 13, 2019 - Elton John, the number one top-performing solo male artist, announced 24 new concert dates to his sold out Farewell Yellow Brick Road Tour. These new dates complete the second year of the North American leg of Elton’s three-year worldwide tour, counting 43 dates in 2020. The Farewell Yellow Brick Road Tour will be making stops in new cities across North America such as Hershey, PA, Greensboro, NC, Knoxville, TN, Fargo, ND, and N. Little Rock, AR. In addition to the new markets, Elton will return to cities including Toronto, ON, Miami, FL, Chicago, IL, Houston, TX, and Kansas City, MO. The tour will conclude in 2021 and is promoted by AEG Presents. Elton wraps 2019 with one of his most successful years to date. In addition to the incredible success of the tour, Rocketman has drawn commercial success and rave reviews, as has Elton’s memoir, Me, which hit #1 on the New York Times Best Sellers list. The Farewell Yellow Brick Road Tour marks the superstar’s last-ever tour, the end of half a century on the road for one of pop culture’s most enduring performers. -

Proust's Medusa: Ovid, Evolution, and Modernist Metamorphosis

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2015 Proust's Medusa: Ovid, Evolution, and Modernist Metamorphosis Gregory John Mercurio Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1053 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] PROUST’S MEDUSA: OVID, EVOLUTION, AND MODERNIST METAMORPHOSIS by GREGORY JOHN MERCURIO A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2015 ii © 2015 GREGORY JOHN MERCURIO All Rights Reserved iii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in English in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Joshua Wilner 4/24/2015 Joshua Wilner Date Chair of Examining Committee Mario DiGangi 4/28/2015 Mario DiGangi Date Executive Officer Wayne Koestenbaum Mary Ann Caws Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv Abstract PROUST’S MEDUSA: OVID, EVOLUTION AND MODERNIST METAMORPHOSIS by Gregory John Mercurio Advisor: Joshua Wilner Ovid’s Metamorphoses has served as an indispensible text for Modernism, not least for such foundational Modernists as T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound and Wyndham Lewis. This dissertation examines how these writers characteristically employ Ovidian metamorphoses with a specifically evolutionary inflection, particularly in a post- Darwinian world informed by varying –often authoritarian– notions of biological adaptation, as well as an increasing emphasis on Mendalian genetics as the determining factor in what would become known as the Modern Synthesis in evolutionary theory. -

Pianos in Early Minnesota

MR. HOLMQUIST, a resident of St. Paul, operates a piano tuning and rebuilding business. He here combines his knowledge of these instruments with a strong interest in Minnesota history. of th Fi®m@@f i Pianos in Early Minnesota DONALD C. HOLMQUIST FORT SNELLING, situated high on a bluff been among his most valued possessions. overlooking the confluence of the Minnesota The English diarist Samuel Pepys noted this and Mississippi rivers, was responsible for in 1666 when he described the flight of peo many of Minnesota's cultural "firsts," in ple from the London fire and remarked that cluding the area's first known piano. At this one out of every three boats had in it a vir outpost of the white man's culture in what ginal (one of the many keyboard precursors was otherwise a vast expanse of wdlderness, of the piano). Similarly, in the 1820s when the wife of Captain Joseph Plympton arrived Mrs. Plympton brought the first piano to as a newlywed in 1824. The source of the Minnesota, we can assume that she did so Mississippi River would be unknown for because it was one of her most cherished another eight years and only the scattered belongings.2 posts of trappers and traders represented In the 1820s the piano was unlike the the economy of what was to become Minne instrument we know today. Although it had sota Territory twenty-five years later. None been invented in Italy in 1709 by Bartolom- theless, to the newly completed fort, then meo Cristofori, it did not become popular the northwesternmost army post in the for over fifty years. -

Puccini — TOSCA

Puccini — TOSCA TOSCA Leaves Audience in a Good Mood, Wanting More! "The traveling production of TOSCA by Teatro Lirico D'Europa left the CAPACITY audience in a good mood, wishing for more. Soprano, Victoria Litherland, was excellent in the title role. She has sung TOSCA before with the Austin Lyric Opera and last week was in Seattle, starring in MANON LESCAUT. She was paired well with tenor, Cesar Hernandez as Mario. Baritone, Vailry Ivanov was appropriately villainous as Scarpia, emphasizing the character's sadistic side rather than his mock piety. The secondary characters were well sung. The sets and costumes were first rate. Everyone deserved the long standing ovation at the final curtain." PORTLAND PRESS HERALD — Christopher Hyde — February 2004 Teatro Lirico's TOSCA Comes Up Big! “Everything about Friday's TOSCA, the outstanding final program in the Symphony Society's International Series, was big. From the moment the curtain rose, it was clear that the nearly 50 members of Teatro Lirico's orchestra were too many for Peabody Auditorium's pit. The result was a voluminous sound, just right for the outsized passions in the opera and for the singers who expressed them. Under the direction of Giorgio Lalov, the focus is always firmly on the romantic tragedy TOSCA represents. Teatro Liricoʼs cast, elegantly costumed and supported by an orchestra able to express the operas immense emotions, was tremendous in their ability to make every nuance felt. In the title role, the young American soprano shone. Pearce's voice, rich and warm, shifted with emotions that spanned the gamut, and her acting made marvelously theatrical gestures entirely believable.