A New Global Citizen Science Project Focused on Moths

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identification of Heterorhabditis

Fundam. appl. Nemawl., 1996,19 (6),585-592 Identification of Heterorhabditis (Nenlatoda : Heterorhabditidae) from California with a new species isolated from the larvae of the ghost moth Hepialis californicus (Lepidoptera : Hepialidae) from the Bodega Bay Natural Reserve S. Patricia STOCK *, Donald STRONG ** and Scott L. GARDNER *** * C.E.PA. \I.E. - National University of La Plata, La Plata, Argentina, and Department ofNematology, University ofCalifornia, Davis, CA 95616-8668, USA, 'k* Bodega Bay lVlarine LaboratDl), University ofCalifomia, Davis, CA 95616-8668, USA and ~,M Harold W. iVlanler Laboratory ofParasitology, W-529 Nebraska Hall, University ofNebraska State Museum, University ofNebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, NE 68588-0514, USA. Acceptee! for publication 3 November 1995. Summary - Classical taxonorny together with cross-breeding tests and random ampWied polymorphie DNA (RAPD's) were used to detect morphological and genetic variation bet\veen populations of Helerorhabdùis Poinar, 1975 from California. A new species, Helerarhabdùis hepialius sp. n., recovered from ghost moth caterpillars (Hepialis cali/amieus) in Bodega Bay, California, USA is herein described and illustrated. This is the eighth species in the genus Helerorhabdùis and is characterized by the morphology of the spicules, gubernaculum, the female's tail, and ratios E and F of the infective juveniles. Information on its bionomics is provided. Résumé - Identification d'Heterorhabditis (Nematoda : Heterorhabditidae) de Californie dont une nouvelle espèce isolée de larves d'Hepialius californicus (Lepidoptera : Hepialidae) provenant de la réserve naturelle de la baie de Bodega - Les méthodes de taxonomie classique de même que des essais de croisement et l'amplification au hasard de l'ADN polymorphique (RAPD) ont été utilisés pour détecter les différences morphologiques et génétiques entre populations d'Helerorhab ditis Poinar, 1975 provenant de Californie. -

Lepidoptera: Hepialidae: Endoclita, Palpifer, and Hepialiscus)

OPEN ACCESS The Journal of Threatened Taxa fs dedfcated to bufldfng evfdence for conservafon globally by publfshfng peer-revfewed arfcles onlfne every month at a reasonably rapfd rate at www.threatenedtaxa.org . All arfcles publfshed fn JoTT are regfstered under Creafve Commons Atrfbufon 4.0 Internafonal Lfcense unless otherwfse menfoned. JoTT allows unrestrfcted use of arfcles fn any medfum, reproducfon, and dfstrfbufon by provfdfng adequate credft to the authors and the source of publfcafon. Journal of Threatened Taxa Bufldfng evfdence for conservafon globally www.threatenedtaxa.org ISSN 0974-7907 (Onlfne) | ISSN 0974-7893 (Prfnt) Communfcatfon Forest ghost moth fauna of northeastern Indfa (Lepfdoptera: Hepfalfdae: Endoclfta , Palpffer , and Hepfalfscus ) John R. Grehan & Vfjay Anand Ismavel 26 March 2017 | Vol. 9| No. 3 | Pp. 9940–9955 10.11609/jot. 3030 .9. 3.9940-9955 For Focus, Scope, Afms, Polfcfes and Gufdelfnes vfsft htp://threatenedtaxa.org/About_JoTT.asp For Arfcle Submfssfon Gufdelfnes vfsft htp://threatenedtaxa.org/Submfssfon_Gufdelfnes.asp For Polfcfes agafnst Scfenffc Mfsconduct vfsft htp://threatenedtaxa.org/JoTT_Polfcy_agafnst_Scfenffc_Mfsconduct.asp For reprfnts contact <[email protected]> Publfsher/Host Partner Threatened Taxa Journal of Threatened Taxa | www.threatenedtaxa.org | 26 March 2017 | 9(3): 9940–9955 Forest ghost moth fauna of northeastern India Communication (Lepidoptera: Hepialidae: Endoclita, Palpifer, and Hepialiscus) 1 2 ISSN 0974-7907 (Online) John R. Grehan & Vijay Anand Ismavel ISSN 0974-7893 (Print) 1 Research Associate, Section of Invertebrate Zoology, Carnegie Museum of Natural History, OPEN ACCESS 4400 Forbes Avenue, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA 2 Makunda Christian Hospital, Bazaricherra, Karimganj District, Assam 788727, India 1 [email protected] (corresponding author), 2 [email protected] Abstract: Taxonomic and biological information is reviewed for the forest Hepialidae of northeastern India, a poorly known group of moths in a region known for the global significance of its biodiversity. -

Scottish Borders Newsletter Spring 2018

Borders Newsletter Issue 20 Spring 2018 http://eastscotland-butterflies.org.uk/ https://www.facebook.com/EastScotlandButterflyConservation https://www.facebook.com/groups/eastscottishmoths/ Welcome to the latest issue of our newsletter for Butterfly Conservation Let’s Celebrate and Keep up the Good Work members and many other people living in the Scottish Borders and further afield. Please forward it to This year marks the 50th anniversary of the creation of Butterfly Conservation others who have an interest in and the organisation is rightly proud of the practical work it has done to help butterflies & moths and who might like to read it and be kept in touch with our our native butterflies and moths. Equally valuable perhaps is the raising of activities. awareness amongst the public and politicians of the importance of these Barry Prater insects and the roles they play. These achievements are reflected in our [email protected] growing membership and the increased frequency we are contacted by Tel 018907 52037 individuals, local groups and most significantly are asked for conservation advice by the planning and forestry agencies. So to help celebrate this anniversary do try and join in with one or more of the bumper range of outdoor Contents events coming up over the summer. And once again the Big Butterfly Count Summer events in 2018 ........Barry Prater will take place over the three weeks 20 July to 12 August Orange Footman, new to Scotland http://www.bigbutterflycount.org/ – there must be a few warm sunny days …………........................Andrew Bramhall then when you can get out and do some counting! A New Universe ….................. -

The Complete Mitochondrial Genomes of Two Ghost Moths, Thitarodes

Cao et al. BMC Genomics 2012, 13:276 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/13/276 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access The complete mitochondrial genomes of two ghost moths, Thitarodes renzhiensis and Thitarodes yunnanensis: the ancestral gene arrangement in Lepidoptera Yong-Qiang Cao1,2†, Chuan Ma3†, Ji-Yue Chen1 and Da-Rong Yang1* Abstract Background: Lepidoptera encompasses more than 160,000 described species that have been classified into 45–48 superfamilies. The previously determined Lepidoptera mitochondrial genomes (mitogenomes) are limited to six superfamilies of the lineage Ditrysia. Compared with the ancestral insect gene order, these mitogenomes all contain a tRNA rearrangement. To gain new insights into Lepidoptera mitogenome evolution, we sequenced the mitogenomes of two ghost moths that belong to the non-ditrysian lineage Hepialoidea and conducted a comparative mitogenomic analysis across Lepidoptera. Results: The mitogenomes of Thitarodes renzhiensis and T. yunnanensis are 16,173 bp and 15,816 bp long with an A + T content of 81.28 % and 82.34 %, respectively. Both mitogenomes include 13 protein-coding genes, 22 transfer RNA genes, 2 ribosomal RNA genes, and the A + T-rich region. Different tandem repeats in the A + T-rich region mainly account for the size difference between the two mitogenomes. All the protein-coding genes start with typical mitochondrial initiation codons, except for cox1 (CGA) and nad1 (TTG) in both mitogenomes. The anticodon of trnS(AGN) in T. renzhiensis and T. yunnanensis is UCU instead of the mostly used GCU in other sequenced Lepidoptera mitogenomes. The 1,584-bp sequence from rrnS to nad2 was also determined for an unspecified ghost moth (Thitarodes sp.), which has no repetitive sequence in the A + T-rich region. -

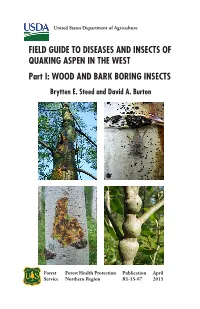

FIELD GUIDE to DISEASES and INSECTS of QUAKING ASPEN in the WEST Part I: WOOD and BARK BORING INSECTS Brytten E

United States Department of Agriculture FIELD GUIDE TO DISEASES AND INSECTS OF QUAKING ASPEN IN THE WEST Part I: WOOD AND BARK BORING INSECTS Brytten E. Steed and David A. Burton Forest Forest Health Protection Publication April Service Northern Region R1-15-07 2015 WOOD & BARK BORING INSECTS WOOD & BARK BORING INSECTS CITATION Steed, Brytten E.; Burton, David A. 2015. Field guide to diseases and insects FIELD GUIDE TO of quaking aspen in the West - Part I: wood and bark boring insects. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Forest Health Protection, Missoula DISEASES AND INSECTS OF MT. 115 pp. QUAKING ASPEN IN THE WEST AUTHORS Brytten E. Steed, PhD Part I: WOOD AND BARK Forest Entomologist BORING INSECTS USFS Forest Health Protection Missoula, MT Brytten E. Steed and David A. Burton David A. Burton Project Director Aspen Delineation Project Penryn, CA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Technical review, including species clarifications, were provided in part by Ian Foley, Mike Ivie, Jim LaBonte and Richard Worth. Additional reviews and comments were received from Bill Ciesla, Gregg DeNitto, Tom Eckberg, Ken Gibson, Carl Jorgensen, Jim Steed and Dan Miller. Many other colleagues gave us feedback along the way - Thank you! Special thanks to Betsy Graham whose friendship and phenomenal talents in graphics design made this production possible. Cover images (from top left clockwise): poplar borer (T. Zegler), poplar flat head (T. Zegler), aspen bark beetle (B. Steed), and galls from an unidentified photo by B. Steed agent (B. Steed). We thank the many contributors of photographs accessed through Bugwood, BugGuide and Moth Photographers (specific recognition in United States Department of Agriculture Figure Credits). -

Entomologiske Meddelelser Entomologiske Meddelelser

EntomologiskeEntomologiske MeddelelserMeddelelser BIND 83 : HEFTE 1 Juni 2015 KØBENHAVN Entomologiske Meddelelser Udgives af Entomologisk Forening i København og sendes gratis til alle medlemmer af denne forening. Abonnement kan tegnes af biblioteker, institutioner, boghandlere m.fl. Prisen herfor er 450 kr. årligt. Hvert år afsluttes et bind, der udsendes fordelt på 2 hefter. Anmodning om tegning af abonnement sendes til kassereren (se omslagets side 3).» Redaktør: Hans Peter Ravn, IGN, Københavns Universitet, Rolighedsvej 23, 1859 Frb. C. Manuskripter skal fremover sendes til: Knud Larsen, Røntoftevej 33, 2870 Dyssegård, [email protected] Entomologiske Meddelelser - a Danish journal of Entomology Is published by the Entomological Society of Copenhagen. The Journal brings both original and review papers in entomology, and appears with two issues a year. The papers appear chiefly in Danish with extensive abstracts in English of all information of value for international entomology. The journal is free of charge to members of the Entomological Society of Copenhagen. Membership costs 250 Danish kroner a year. School pupils and stu- dents may have membership for just 100 DKR, but they will receive a PDF-copy of the journal only. Application for membership and subscription orders should be sent to the secretary of the society, c/o Zoological Museum, Universitetsparken 15, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark. Manuskriptets udformning m.v. Entomologiske Meddelelser optager først og fremmest originale afhandlinger og andre meddelelser om dansk entomologi (inkl.. Færøerne og Grønland). Hovedvægten lægges på artikler, der bidrager til kendskab til den danske entomofauna (insekter, spindlere, tusindben og skolopendere), til nordeuropæiske og arktiske insekters taksonomi, økologi, funktionsmorfologi, biogeografi, faunistik, m.v. -

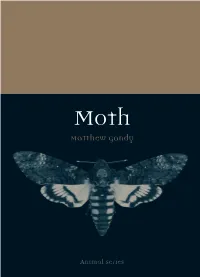

Matthew Gandy Matthew Gandy

cyanblack 8005 c spine 16 mm process black | process cyan | pms 8005 c (c) trim fold fold trim ‘A bold and fascinating series’ The Independent ‘This series . calls itself “a new kind of animal history”. M It is, splendidly, even brilliantly, so. I have nothing but praise for it’ oth The Spectator Unlike their gaudy day-flying cousins, moths seem to reside in the shadows Gandy Matthew as denizens of the night, circling around street lights or caught momentarily in the glare of car headlights on a country lane. There are, however, many more species of day-flying moths than there are of butterflies, and as for colours and patterns, many moths rival or even exceed butterflies in the dazzling range oth of their markings. M The study of moths formed an integral part of early natural history and many thousands of drawings, paintings and physical specimens remain in museum Matthew Gandy collections around the world. In recent years there has been a renewed surge of interest in moths facilitated by advances in digital photography. There is a rich history of the naming of moths in early cultures of nature: from the Merveille du Jour, the Green-brindled Crescent, the Clifden Nonpareil and the strikingly named Death’s-head Hawk-moth, these creatures evoke a sense of wonder that connects such disparate fields as folklore, literature, the history of place and early scientific texts. Matthew Gandy is Professor of Geography at the University of Cambridge. His previous books include Concrete and Clay: Reworking Nature in New York City (2002) and The Fabric of Space: Water, Modernity, and the Urban Imagination (2014). -

What to See at Hoe Grange Quarry

Conservation Activities LIST OF MOTH ATTRACTED TO MV LIGHTS DURING 2018 AT HOE GRANGE QUARRY Moth Species Triodia sylvina Orange Swift Pheosia tremula Swallow Prominent Korscheltellus lupulina Common Swift Ptilodon capucina Coxcomb Prominent Korscheltellus fusconebulosa Map-winged Swift Rivula sericealis Straw Dot Hepialus humuli Ghost Moth Hypena proboscidalis Snout Yponomeuta evonymella Bird-cherry Ermine Spilosoma lutea Buff Ermine Ypsolopha scabrella a moth Spilosoma lubricipeda White Ermine Prays fraxinella Ash Bud Moth Phragmatobia fuliginosa Ruby Tiger Coleophora mayrella a moth Eilema griseola Dingy Footman Blastobasis adustella a moth Eilema lurideola Common Footman Amblyptilia acanthadactyla Beautiful Plume Autographa gamma Silver Y Emmelina monodactyla Common Plume Plusia festucae Gold Spot Pandemis corylana Chequered Fruit-tree Tortrix Acronicta rumicis Knot Grass Pseudargyrotoza conwagana a moth Allophyes oxyacanthae Green-brindled Crescent Agapeta hamana a moth Phlogophora meticulosa Angle Shades Celypha lacunana a moth Eucosma hohenwartiana a moth Udea lutealis a moth Udea prunalis a moth Frosted Orange Udea olivalis a moth Pleuroptya ruralis Mother of Pearl photo Bill Williams Scoparia subfusca a moth Scoparia pyralella a moth Eudonia lacustrata a moth Chrysoteuchia culmella Garden Grass-veneer Crambus pascuella a moth Gortyna flavago Frosted Orange Agriphila tristella a moth Luperina testacea Flounced Rustic Agriphila straminella a moth Photedes minima Small Dotted Buff Catoptria falsella a moth Apamea remissa Dusky Brocade -

In This Issue: Upcoming Programs: None Till September. See You at The

Volume 18, Number 2 June 2017 G’num* The newsletter of the Washington Butterfly Association P.O. Box 31317 Seattle WA 98103 http://wabutterflyassoc.org *G’num is the official greeting of WBA. It is derived from the name of common Washington butterfly food plants, of the genus Eriogonum. In this issue: Amazing Monarchs p 2 President’s Message p 4 Watching Washington Butterflies p 5 Field Trip Schedule p 9 Canyon. (M. Weiss) (M. Canyon. Waterworks Party, Puddle Blues Melanie Weiss, with broken wrist, photographs an Indra Swallowtail at Waterworks Canyon. (Cathy Clark) Upcoming Programs: None till September. See you at the Conference! Cascade Butterfly Project This citizen science project, now in its seventh year, monitors butterflies and plants in six protected areas of the Cas- cade Mountains in Washington to determine how they are affected by climate change. WBA member Melanie Weiss has been a volunteer with the program since the beginning and is the lead on the Naches Loop trail at Chinook Pass at Mt. Rainier. She is looking for enthusiastic WBA members who would like to volunteer a day on this beautiful Mt. Rainier trail counting butterflies and monitoring plant phenology. There will be two training days: one at Sauk Moun- tain near Sedro Wooley on June 28 or one at Sunrise at Mt. Rainier on either July 25 or 26 (to be decided soon). How- ever, if you are unable to make either of these trainings, you will still be able to participate by getting training in the field when you participate. This is a great way to learn butterfly species and get out in the alpine country. -

Colour Morphs of the Ghost Moth Hepialus Humuli L. (Lepidoptera, Hepialidae) in the Faroe Islands

Colour morphs of the Ghost Moth Hepialus humuli L. (Lepidoptera, Hepialidae) in the Faroe Islands Janus Hansen & Jens-Kjeld Jensen Hansen, J. & J.-K. Jensen: Colour morphs of the Ghost Moth Hepialus humuli L. (Lepidoptera, Hepialidae) in the Faroe Islands. Ent. Meddr 73: 123-130. Copenhagen, Denmark, 2005. ISSN 0013-8851. Over a period of 10 years, 2,435 male Ghost Moths Hepialus humuli thulensis from the Faroe Islands were captured for a study of male colour morphs. The pattern of local variation found in the Faroe Islands supports the hypothesis that cryptic colouration is an adaptation to predation pressure from birds. Janus Hansen, The Faroese Museum of Natural History, FO-100 Tórshavn, Faroe Islands. Jens-Kjeld Jensen, FO-270 Nólsoy, Faroe Islands. Introduction The Ghost Moth Hepialus humuli L. is a common species widely distributed throughout Europe (Karsholt & Razowski, 1996). The Hepialidae is a primitive family of Lepidop- tera. In mainland Europe the male upper wing has a bright glossy white colour, while the female is of a less conspicuous yellow to brown colour. The female wingspan (60-75 mm) is larger than that of males (45-60 mm) as is common in the Lepidoptera. The male’s hind legs are set with large bushy hairs (fig. 1), from which a pheromone can be excreted that attracts females by a smell similar to that of Wild Carrot (Daucus carota L.) (Hoffmeyer, 1974; Skinner, 1984). At twilight, the pale male Ghost Moths will hover over the grass to attract females. After having mated, the female will fly over the grass and simply drop the eggs to the ground (Langer, 1957). -

Third Symposium on Hemlock Woolly Adelgid in the Eastern United States Asheville, North Carolina February 1-3, 2005

Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER Hemlock Woolly Adelgid THIRD SYMPOSIUM ON HEMLOCK WOOLLY ADELGID IN THE EASTERN UNITED STATES ASHEVILLE, NORTH CAROLINA FEBRUARY 1-3, 2005 Brad Onken and Richard Reardon, Compilers Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team—Morgantown, West Virginia FHTET-2005-01 U.S. Department Forest Service June 2005 of Agriculture Most of the abstracts were submitted in an electronic format, and were edited to achieve a uniform format and typeface. Each contributor is responsible for the accuracy and content of his or her own paper. Statements of the contributors from outside of the U.S. Department of Agriculture may not necessarily reflect the policy of the Department. Some participants did not submit abstracts, and so their presentations are not represented here. The use of trade, firm, or corporation names in this publication is for the information and convenience of the reader. Such use does not constitute an official endorsement or approval by the U.S. Department of Agriculture of any product or service to the exclusion of others that may be suitable. References to pesticides appear in some technical papers represented by these abstracts. Publication of these statements does not constitute endorsement or recommendation of them by the conference sponsors, nor does it imply that uses discussed have been registered. Use of most pesticides is regulated by state and federal laws. Applicable regulations must be obtained from the appropriate regulatory agency prior to their use. CAUTION: Pesticides can be injurious to humans, domestic animals, desirable plants, and fish and other wildlife if they are not handled and applied properly. -

Description of Species Colour Identification Guide to Moths of the British Isles

Description of Species Colour Identification Guide to Moths of the British Isles Family: Hepialidae Gold Swift 16 Hepialus hecta Linnaeus This family is a member of the Exoporia, a primitive Plate 1: 13-15 suborder of Lepidoptera, comprising many medium- to Imago. 26-32 mm. Resident. Both sexes come sparingly large-sized species, of which five are found in the British to light. The males appear commonly at dusk and emit Isles. a scent likened to that of ripe pineapple. In favourable The adults are characterized by their elongate wings and conditions there is a strong dawn flight with the females very short antennae. The main flight is from a short time predominating. Single-brooded, flying from mid-June to before dusk until dark, although some individuals mid-July, frequenting a variety of habitats such as continue to fly intermittently throughout the night. Both woodland rides, parkland, commons and heathland. sexes are attracted to light. Local, but not uncommon over much of the British Isles; The eggs are broadcast by the female as she flies just occurring in Scotland as far north as Caithness and above the vegetation. Sutherland and as far west as the Inner Hebrides. The long, cylindrical and whitish larvae feed on the roots Larva. July to June of the third year on the stems and of various plants and pupate in the ground. roots of bracken and other plants; feeding internally until the final instar. Ghost Moth 14 Overwinters twice as a larva. Hepialus humuli humuli Linnaeus Plate 1: 9-10 Common Swift 17 Imago. 44-60 mm.