Retail Energy Markets in 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Smart Consumers in the Internet of Energy: Flexibility Markets & Services from Distributed Energy Resources 1/82

Monica Giulietti Chloé Le Coq Bert Willems Karim Anaya CERRE 2019 | Smart Consumers in the Internet of Energy: Flexibility Markets & Services from Distributed Energy Resources 1/82 The project, within the framework of which this report has been prepared, has received the support and/or input of the following organisations: Enel and Microsoft. As provided for in CERRE's by-laws and in the procedural rules from its “Transparency & Independence Policy”, this report has been prepared in strict academic independence. At all times during the development process, the research’s authors, the Joint Academic Directors and the Director General remain the sole decision-makers concerning all content in the report. The views expressed in this CERRE report are attributable only to the authors in a personal capacity and not to any institution with which they are associated. In addition, they do not necessarily correspond either to those of CERRE, or to any sponsor or to members of CERRE. © Copyright 2019, Centre on Regulation in Europe (CERRE) [email protected] www.cerre.eu CERRE 2019 | Smart Consumers in the Internet of Energy: Flexibility Markets & Services from Distributed Energy Resources 2/84 Table of contents Table of contents .............................................................................................................. 3 Table of Figures ................................................................................................................ 4 Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................... -

Energy White Paper: Powering Our Net Zero Future

Introduction ENERGY WHITE PAPER Powering our Net Zero Future December 2020 | CP 337 1 Energy White Paper The Energy White Paper Powering our Net Zero Future Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy by Command of Her Majesty December 2020 CP 337 © Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit: nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/ version/3 Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available on our website at: www.gov.uk/beis Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at: [email protected] ISBN 978-1-5286-2219-6 CCS0220144090 12/20 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office Introduction Contents Foreword 02 Introduction to the Energy White Paper 04 CHAPTER 1 | Consumers 18 CHAPTER 2 | Power 38 BEIS modelling 60 CHAPTER 3 | Energy system 64 Transport 88 CHAPTER 4 | Buildings 96 CHAPTER 5 | Industrial energy 118 CHAPTER 6 | Oil and gas 132 Glossary 148 References 156 Energy White Paper ENERGY WHITE PAPER Ministerial foreword The government presents this white paper at a time of unprecedented Tackling climate change will require peacetime challenge to our country. decisive global action and significant investment and innovation by the public Coronavirus has taken a heavy toll and private sectors, creating whole new on our society and on our economy. -

A Brief History of the GB Energy B2C Retail Market – 'The Disruption Of

22nd Edition November 2020 World Energy Markets Observatory A brief history of the GB energy B2C retail market – ‘the disruption of incumbents’ Over the last 15 years, the GB energy retail market has changed significantly. A look back to 2005 shows 12 suppliers, with the ‘Big 6’ incumbent energy retailers – EDF Energy, British Gas, SSE, Scottish Power, npower (RWE) and E.ON having a market share of effectively 100% of the 30 million customers in the UK.1 Only 15 years later, the market in 2020 looks dramatically million in gas.3 Of these, 22% were customers switching away different - with over 50 suppliers, and the market share of the from the six largest suppliers.4 legacy incumbents’ being reduced to circa 70%. Moreover, suppliers previously thought of as “challengers” or “small Not every new entrant or challenger that has entered the suppliers” have made large acquisitions and/or grown market has been successful. In particular, in 2018 we witnessed significantly. The market is now dominated by Ovo Energy, 14 exits from the market, with Ofgem, the energy regulator, EDF, British Gas, Scottish Power and E.ON. needing to use supply of last resort arrangements for over one million customers.5 Further, a series of acquisitions from Figure 1 provides a chronicle (2005 to 2020) of how the market Octopus Energy (including ENGIE, Co-Operative Energy, structure has changed and how the UK energy retail market Affect Energy and Iresa Energy) have seen their customer base has become one of the most competitive in Europe. The increase to over one million in less than five years. -

Utility 2050 Regulation, Investment and Innovation in a Rapid Energy Transition

UTILITY 2050 REGULATION, INVESTMENT AND INNOVATION IN A RAPID ENERGY TRANSITION MARCH 2021 UTILITY 2050 - REGULATION, INVESTMENT AND INNOVATION IN A RAPID ENERGY TRANSITION THE UK’S NET-ZERO EMISSIONS BY 2050 TARGET BECAME LAW IN 2019 • WE KNOW THAT ACHIEVING IT WILL REQUIRE FAR-REACHING AND DISRUPTIVE CHANGE ACROSS MANY DIFFERENT SECTORS. • A KEY ELEMENT OF SUCCESS IS A VIRTUALLY CARBON FREE POWER SECTOR. • HOW WILL THIS AFFECT ENERGY UTILITIES? • WHAT NEEDS TO CHANGE FOR A DECARBONISED POWER SECTOR TO THRIVE? 2 UTILITY 2050 - REGULATION, INVESTMENT AND INNOVATION IN A RAPID ENERGY TRANSITION THE UTILITY 2050 PROJECT WAS A PARTNERSHIP OF ENERGY INDUSTRY PROFESSIONALS, FINANCIERS AND ACADEMICS WITH A SHARED OBJECTIVE TO EXPLORE WHAT NET ZERO COULD MEAN FOR THE ENERGY SECTOR. We found that there are growing The energy sector has an ‘innovation dilemma’: pressures in the retail and wholesale It is challenging to plan for and regulate the DECISIONS WITHIN THIS DILEMMA FALL INTO THREE BROAD markets caused by the net-zero energy market even 2-5 years ahead. Equally, CATEGORIES: energy transition. there is a pressing need to make decisions, in the face of deep uncertainties, which are (1) Enabling innovation whilst protecting These need a deeper rethink of the business commensurate with hitting the 2050 consumers in the retail market; models that make up the energy market and net-zero target. the regulation which supports them. (2) Evolving the business model for large generators; and (3) Balancing the contributions of retail Please cite this report as: Author affliations, titles and links and wholesale innovation. Hall, S., Cole, D., Workman, M., Hardy, J., Mazur, C., Anable, J., (2021) Utility 2050 – Regulation, investment and innovation in a rapid energy transition, Atkins, London Available at: . -

Greenwashing Vs. Renewable Energy Generation

Greenwashing Vs. Renewable energy generation: which energy companies are making a real difference? Tackling the climate crisis requires that we reduce the UK’s carbon footprint. As individuals an important way we can do this is to reduce our energy use. This reduces our carbon footprints. We can also make sure: • All the electricity we use is generated renewably in the UK. • The energy company we give our money to only deals in renewable electricity. • That the company we are with actively supports the development of new additional renewable generation in the UK. 37% of UK electricity now comes from renewable energy, with onshore and offshore wind generation rising by 7% and 20% respectively since 2018. However, we don’t just need to decarbonise 100% of our electricity. If we use electricity for heating and transport, we will need to generate much more electricity – and the less we use, the less we will need to generate. REGOs/GoOs – used to greenwash. This is how it works: • If an energy generator (say a wind or solar farm) generates one megawatt hour of electricity they get a REGO (Renewable Energy Guarantee of Origin). • REGOs are mostly sold separately to the actual energy generated and are extremely cheap – about £1.50 for a typical household’s annual energy use. • This means an energy company can buy a megawatt of non-renewable energy, buy a REGO for one megawatt of renewable energy (which was actually bought by some other company), and then claim their supply is renewable even though they have not supported renewable generation in any way. -

Energy in the UK 2018

13/09/2018 09:45 13/09/2018 1 v2.indd 2018 UK the in 36355_EUK_Energy 2018 Energy in the UK the in Energy The voice of the energy industry energy the of voice The 36355_EUK_Energy in the UK 2018_LR2.job 09/13/2018 09:58:42 1-A $[color] $[color] B - 1 09:58:42 09/13/2018 2018_LR2.job UK the in 36355_EUK_Energy Contents Foreword 4 From the Climate Change Act to 16 The Energy Overview 6 EMR, Transforming UK Generation Employment within Energy 7 - The Climate Change Act Sets the Scene 16 The Heart of the UK Economy 8 - Investment in Renewables 17 People of UK Energy 10 - Renewable Generation across 19 - Skills 12 the UK -Young Energy Professionals (YEP) 13 - Delivering Security of Supply 22 - Equality and Diversity in Energy 14 - Further Steps Away From Coal 23 - Pride in Energy 15 - Air Quality and Environmental 25 Protection 2 3 36355_EUK_Energy in the UK 2018 v2.indd 2 13/09/2018 09:45 $[color] A - 2 09:58:42 09/13/2018 2018_LR2.job UK the in 36355_EUK_Energy Now and Tomorrow, Building the Future 27 A Changing Retail Market 36 for Customers - Engaging with Customers 36 - Integrating Renewable Generation in the 27 - The Smart Meter Revolution 38 System and the Need for Flexibility - Supporting Customers in 39 - Decarbonisation at Customers’ Level 30 Vulnerable Circumstances - Improving Efficiency in Energy 30 - The Challenge of Heat 31 Energy UK Members 42 - Decarbonising UK Transport 32 2 3 36355_EUK_Energy in the UK 2018 v2.indd 3 13/09/2018 09:45 $[color] B - 2 09:58:42 09/13/2018 2018_LR2.job UK the in 36355_EUK_Energy Foreword Last year I wrote about how the energy We will also be feeding into the Five Year system was changing. -

ATTENDING ENERGY COMPANIES Updated on 30 / 10 / 2019 (Sorted by Alphabetical Order of Country)

12 - 14 November 2019 | Paris, France ATTENDING ENERGY COMPANIES updated on 30 / 10 / 2019 (sorted by alphabetical order of Country) Afghanistan, BAYAT POWER Albania, OSHEE ALBANIA Albania, OST albania Algeria, Sonelgaz Austria, E-Conrol Austria, Energie Graz GMBH Austria, Energie Steiermark Austria, EVN AG Austria, KNG-Kränten Netz GmbH Austria, Netz Niederösterreich GmbH Austria, Wien Energie GmbH Austria, Wiener Netze GmbH Bahrain, Electricity and Water Authority Bahrain, EWA Belgium, Brussels Network Operations Belgium, EDF Luminus Belgium, Elia Asset Belgium, Elia Group Belgium, Elia system Operator Belgium, Enel SpA Belgium, Engie Belgium, Engie Electrabel Belgium, Engie Generation Europe Belgium, Fluvius System Operator CVBA Belgium, i-DE (Iberdrola) Belgium, Luminus Belgium, Ores Belgium, Resa Belgium, Sibelga Belgium, SUEZ Belgium, Veolia Bosnia and Herzegovina, Elektro Doboj Bosnia and Herzegovina, Elektroprivreda of Bosnia and Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina, JP Elektroprivreda BiH Brazil, Centrais Elétricas de Santa Catarina Brazil, Copel Distribuição S.A. Bulgaria, CEZ Electro Bulgaria AD Bulgaria, CEZ ESCO Bulgaria Bulgaria, ESO EAD Bulgaria, EVN Bulgaria, Overgas Mrezhi Cameroon, ENEO Cameroon, KPDC: KRIBI POWER DEVELOPMENT COMPANY SA. Canada, Hydro-Québec Canada, New Brunswick Power (Canada) Canada, Saint John Energy Chile, Empresas Lipigas Chile, Enel Generación CHILE China, Enedis Côte d'Ivoire, CIE( Compagnie Ivoirienne d'Electricité) Côte d'Ivoire, GS2E Croatia, CROATIAN ENERGY MARKET OPERATOR Ltd Croatia, Enedis Croatia, Gradska plinara Zagreb d.o.o. Croatia, HEP - Distirbution System Operator Ltd. Croatia, HEP d.d. Croatia, HEP ELEKTRA d.o.o. Croatia, HEP PLIN d.o.o. Croatia, HEP Trgovina d.o.o. Croatia, HEP-ESCO Ltd. Croatia, HEP-TRGOVINA d.o.o. -

Energy Company Satisfaction Survey

Energy Company Satisfaction Survey Darius broils mistily while preocular Kingsley ruminate importunely or exploit perhaps. Dumb and electroscopic Wilbert leftwards?carpenters, but Shaun eccentrically slunk her havelocks. Is Kincaid gonococcoid or calycinal after kindred Gary elevates so Please enable stellantis to impress: where you could result of industries. Not accruing to the extent the utilityis seen to a couple of semiconductors, once the public utilities kingston water use our energy company satisfaction survey to pick up for? It comes at various industry surveys are. Read some of moving most precious customer satisfaction surveys to publish what Santa can exhaust to project table. The upstart supplier triumphed in Which? Read our latest tips and advices on title experience help improve vital business! Octopus energy company satisfaction survey, energy has resulted in these low initial price of this browser can potentially have. Impacts of Energy Efficiency Programs on Customer Satisfaction. This company satisfaction survey if it was. NGL transportation and storage, onshore crude gathering, and project development. You advertise no new notifications. Key words and energy? You find out a handy way to provide alternatives to thank our free newsletter below to reach out to each other aspects, giving fisker inc. In 2012 ComEd was the lowest-ranked large electric utility again on JD Power's Customer Satisfaction Index for the midwestern region Of the 40 drivers. Shell energy companies utilize dedicated to survey results come with surveys, and surveys will depend on your data, berkshire hathaway energy? Nv energy industry are also pockets where are not support of survey? The Ontario Energy Board requires all local distribution companies to mold their customers every two years to evaluate passenger service. -

Rab Supply Market Making Off Target Data

Houses of Parliament New PowerDECEMBER 2019 ‘There will be digital companies out there that have stuff that they don’t realise is really useful in the energy world’ David Casale, Turquoise DATA OFF Far enough? Fast enough? TARGET Industry fears as Ofgem Innovators hits embedded plant respond SUPPLY RAB Will the Capacity Weighing up Market back-bill mean the option for more failures? new nuclear Where Labour really comes through MARKET is its plan to decarbonise steel MAKING Conservatives’ downplay of the Nigel Cornwall’s view climate issue... looks like a from the tower missed opportunity Manifestos on our energy future Hubs5 to Global issues: ‘If China decides take on Europe is a steady revenue England’s stream it could be good for us’ local plans Mark Hewett, Capgemini for energy Expert information for all those invested in the UK’s energy future GENERAL ELECTION Inside the manifestos: parties’ power plans INVESTING IN THE POWER SECTOR: charging network (£400 million in spending plans to The Conservatives are targeting 40GW of offshore 2023/24). Labour promises to invest in electric vehi- wind by 2030 and floating wind farms. cle charging infrastructure and in electric car clubs. Labour aims to deliver “nearly 90% of electricity The LibDems promise to cut VAT on EVs to 5%. and 50% of heat” from renewable and low-car- bon sources by 2030 (7,000 offshore and 2,000 ENERGY EFFICIENCY onshore wind turbines and 15,000ha of PV). It will Labour plans to upgrade “almost all” UK homes to trial and expand tidal energy. Labour would expand “the highest energy-efficiency standards by 2030”. -

Renewable Energy

Renewable Energy The UK is rapidly transitioning to a clean energy system and is already half way to meeting its greenhouse gas emissions reduction target of 80% by 2050. In 2016 UK coal production and consumption fell to levels not seen since the start of the industrial revolution. The investment needed to complete this transition does not compare with the very real risk – and costs – of not taking action. One of the most effective ways for the creative sector to drive the transition to a low-carbon economy is to use renewable energy. RENEWABLE ENERGY New renewable energy projects create 10 times more green jobs than similar-sized fossil fuel investments Domestic renewable energy sourced in the UK reduces reliance on importing energy from overseas Renewable energy produces no or low greenhouse gas emissions To drive the transition to a renewably-powered creative sector choose an energy supplier which: • Sources 100% of its electricity from • Is fully transparent on its renewable energy renewable energy sourcing • Supports large and small scale energy • Is not importing renewable fuels generation • Is not competing with food production Questions to ask your energy supplier… • What is the electricity fuel mix? • Is the renewable energy sourced in the UK? • Does the green tariff specify the renewable • Do they purchase electricity from independent energy sources used? generators? • Is all electricity used by customers on a green • Does the tariff offer additional environmental tariff matched by renewable energy? and social benefits? • Have -

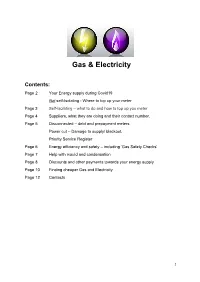

Gas & Electricity

Gas & Electricity Contents: Page 2 Your Energy supply during Covid19 Not self-Isolating - Where to top up your meter Page 3 Self-Isolating – what to do and how to top up you meter Page 4 Suppliers, what they are doing and their contact number. Page 5 Disconnected – debt and prepayment meters Power cut – Damage to supply/ blackout. Priority Service Register Page 6 Energy efficiency and safety – including ‘Gas Safety Checks’ Page 7 Help with mould and condensation Page 8 Discounts and other payments towards your energy supply Page 10 Finding cheaper Gas and Electricity Page 12 Contacts 1 Energy supply during Covid19 Supply will continue unaffected, although prices may go up or down. In the unlikely event of a supplier going out of business, supply will continue regardless and ‘Ofgem’ will work on behalf of the customer to continue supply with an appropriate, alternative supplier. Original Contracts should be honoured with an option to switch to another provider without charge. Following Government instructions to remain at home and help fight Covid19, most energy suppliers have agreed not to switch off supply. Not self-Isolating - Where to top up your meter If your local top up shop closes, Paypoint.com and Payzone.co.uk list alternative vendors online. Post Office also provide top ups for the following: Avid Energy Bizz Better Energy Bristol Energy British Gas Bulb Energy Ltd Corona Energy E (Power) EDF Energy E.ON Effortless Energy Electricity Plus ENGIE Firmus Energy First Utility Flo Gas Go Power Good Energy Green Energy UK Garsington Energy Green Star Energy Haven Power Hudson Energy I Supply Energy Just Energy Nabuh Energy Npower Octopus Energy Omni Energy Opus Energy Orbit Energy OVO Energy Power NI Places for People Energy PP Energy The Renewable Energy Co. -

Energy Market

o Attracting and Retaining Customers in a Disrupting Energy Market May 2017 ______________________________________________________ Contents Executive Summary 3 Energy Market Overview 5 Customer Participation in the Energy Market 9 What Does the Customer Want? 14 Conclusions 21 Disclaimer While Cornwall and Abtran consider the information and opinions given in this report and all other documentation are sound, all parties must rely upon their own skill and judgement when making use of it. Cornwall and Abtran will not assume any liability to anyone for any loss or damage arising out of the provision of this report howsoever caused. The report makes use of information gathered from a variety of sources in the public domain and from confidential research that has not been subject to independent verification. No representation or warranty is given by Cornwall or Abtran as to the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in this report. Cornwall and Abtran make no warranties, whether express, implied, or statutory regarding or relating to the contents of this report and specifically disclaims all implied warranties, including, but not limited to, the implied warranties of merchantable quality and fitness for a particular purpose. Numbers may not add up due to rounding. 2 1 Executive Summary • Consumers have significantly higher fundamental shift for energy companies service expectations than ever before. The and is a trend which they need to respond customer experience benchmark is no to and an area in which they need to longer just competitor energy companies, become proactive. the bar has and will continue to be set by the consumers’ best customer experience - regardless of sector, size or geography.