Mathematics and Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes on Euler's Work on Divergent Factorial Series and Their Associated

Indian J. Pure Appl. Math., 41(1): 39-66, February 2010 °c Indian National Science Academy NOTES ON EULER’S WORK ON DIVERGENT FACTORIAL SERIES AND THEIR ASSOCIATED CONTINUED FRACTIONS Trond Digernes¤ and V. S. Varadarajan¤¤ ¤University of Trondheim, Trondheim, Norway e-mail: [email protected] ¤¤University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA e-mail: [email protected] Abstract Factorial series which diverge everywhere were first considered by Euler from the point of view of summing divergent series. He discovered a way to sum such series and was led to certain integrals and continued fractions. His method of summation was essentialy what we call Borel summation now. In this paper, we discuss these aspects of Euler’s work from the modern perspective. Key words Divergent series, factorial series, continued fractions, hypergeometric continued fractions, Sturmian sequences. 1. Introductory Remarks Euler was the first mathematician to develop a systematic theory of divergent se- ries. In his great 1760 paper De seriebus divergentibus [1, 2] and in his letters to Bernoulli he championed the view, which was truly revolutionary for his epoch, that one should be able to assign a numerical value to any divergent series, thus allowing the possibility of working systematically with them (see [3]). He antic- ipated by over a century the methods of summation of divergent series which are known today as the summation methods of Cesaro, Holder,¨ Abel, Euler, Borel, and so on. Eventually his views would find their proper place in the modern theory of divergent series [4]. But from the beginning Euler realized that almost none of his methods could be applied to the series X1 1 ¡ 1!x + 2!x2 ¡ 3!x3 + ::: = (¡1)nn!xn (1) n=0 40 TROND DIGERNES AND V. -

Calculus Terminology

AP Calculus BC Calculus Terminology Absolute Convergence Asymptote Continued Sum Absolute Maximum Average Rate of Change Continuous Function Absolute Minimum Average Value of a Function Continuously Differentiable Function Absolutely Convergent Axis of Rotation Converge Acceleration Boundary Value Problem Converge Absolutely Alternating Series Bounded Function Converge Conditionally Alternating Series Remainder Bounded Sequence Convergence Tests Alternating Series Test Bounds of Integration Convergent Sequence Analytic Methods Calculus Convergent Series Annulus Cartesian Form Critical Number Antiderivative of a Function Cavalieri’s Principle Critical Point Approximation by Differentials Center of Mass Formula Critical Value Arc Length of a Curve Centroid Curly d Area below a Curve Chain Rule Curve Area between Curves Comparison Test Curve Sketching Area of an Ellipse Concave Cusp Area of a Parabolic Segment Concave Down Cylindrical Shell Method Area under a Curve Concave Up Decreasing Function Area Using Parametric Equations Conditional Convergence Definite Integral Area Using Polar Coordinates Constant Term Definite Integral Rules Degenerate Divergent Series Function Operations Del Operator e Fundamental Theorem of Calculus Deleted Neighborhood Ellipsoid GLB Derivative End Behavior Global Maximum Derivative of a Power Series Essential Discontinuity Global Minimum Derivative Rules Explicit Differentiation Golden Spiral Difference Quotient Explicit Function Graphic Methods Differentiable Exponential Decay Greatest Lower Bound Differential -

Euler and His Work on Infinite Series

BULLETIN (New Series) OF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Volume 44, Number 4, October 2007, Pages 515–539 S 0273-0979(07)01175-5 Article electronically published on June 26, 2007 EULER AND HIS WORK ON INFINITE SERIES V. S. VARADARAJAN For the 300th anniversary of Leonhard Euler’s birth Table of contents 1. Introduction 2. Zeta values 3. Divergent series 4. Summation formula 5. Concluding remarks 1. Introduction Leonhard Euler is one of the greatest and most astounding icons in the history of science. His work, dating back to the early eighteenth century, is still with us, very much alive and generating intense interest. Like Shakespeare and Mozart, he has remained fresh and captivating because of his personality as well as his ideas and achievements in mathematics. The reasons for this phenomenon lie in his universality, his uniqueness, and the immense output he left behind in papers, correspondence, diaries, and other memorabilia. Opera Omnia [E], his collected works and correspondence, is still in the process of completion, close to eighty volumes and 31,000+ pages and counting. A volume of brief summaries of his letters runs to several hundred pages. It is hard to comprehend the prodigious energy and creativity of this man who fueled such a monumental output. Even more remarkable, and in stark contrast to men like Newton and Gauss, is the sunny and equable temperament that informed all of his work, his correspondence, and his interactions with other people, both common and scientific. It was often said of him that he did mathematics as other people breathed, effortlessly and continuously. -

On the Euler Integral for the Positive and Negative Factorial

On the Euler Integral for the positive and negative Factorial Tai-Choon Yoon ∗ and Yina Yoon (Dated: Dec. 13th., 2020) Abstract We reviewed the Euler integral for the factorial, Gauss’ Pi function, Legendre’s gamma function and beta function, and found that gamma function is defective in Γ(0) and Γ( x) − because they are undefined or indefinable. And we came to a conclusion that the definition of a negative factorial, that covers the domain of the negative space, is needed to the Euler integral for the factorial, as well as the Euler Y function and the Euler Z function, that supersede Legendre’s gamma function and beta function. (Subject Class: 05A10, 11S80) A. The positive factorial and the Euler Y function Leonhard Euler (1707–1783) developed a transcendental progression in 1730[1] 1, which is read xedx (1 x)n. (1) Z − f From this, Euler transformed the above by changing e to g for generalization into f x g dx (1 x)n. (2) Z − Whence, Euler set f = 1 and g = 0, and got an integral for the factorial (!) 2, dx ( lx )n, (3) Z − where l represents logarithm . This is called the Euler integral of the second kind 3, and the equation (1) is called the Euler integral of the first kind. 4, 5 Rewriting the formula (3) as follows with limitation of domain for a positive half space, 1 1 n ln dx, n 0. (4) Z0 x ≥ ∗ Electronic address: [email protected] 1 “On Transcendental progressions that is, those whose general terms cannot be given algebraically” by Leonhard Euler p.3 2 ibid. -

List of Mathematical Symbols by Subject from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

List of mathematical symbols by subject From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia This list of mathematical symbols by subject shows a selection of the most common symbols that are used in modern mathematical notation within formulas, grouped by mathematical topic. As it is virtually impossible to list all the symbols ever used in mathematics, only those symbols which occur often in mathematics or mathematics education are included. Many of the characters are standardized, for example in DIN 1302 General mathematical symbols or DIN EN ISO 80000-2 Quantities and units – Part 2: Mathematical signs for science and technology. The following list is largely limited to non-alphanumeric characters. It is divided by areas of mathematics and grouped within sub-regions. Some symbols have a different meaning depending on the context and appear accordingly several times in the list. Further information on the symbols and their meaning can be found in the respective linked articles. Contents 1 Guide 2 Set theory 2.1 Definition symbols 2.2 Set construction 2.3 Set operations 2.4 Set relations 2.5 Number sets 2.6 Cardinality 3 Arithmetic 3.1 Arithmetic operators 3.2 Equality signs 3.3 Comparison 3.4 Divisibility 3.5 Intervals 3.6 Elementary functions 3.7 Complex numbers 3.8 Mathematical constants 4 Calculus 4.1 Sequences and series 4.2 Functions 4.3 Limits 4.4 Asymptotic behaviour 4.5 Differential calculus 4.6 Integral calculus 4.7 Vector calculus 4.8 Topology 4.9 Functional analysis 5 Linear algebra and geometry 5.1 Elementary geometry 5.2 Vectors and matrices 5.3 Vector calculus 5.4 Matrix calculus 5.5 Vector spaces 6 Algebra 6.1 Relations 6.2 Group theory 6.3 Field theory 6.4 Ring theory 7 Combinatorics 8 Stochastics 8.1 Probability theory 8.2 Statistics 9 Logic 9.1 Operators 9.2 Quantifiers 9.3 Deduction symbols 10 See also 11 References 12 External links Guide The following information is provided for each mathematical symbol: Symbol: The symbol as it is represented by LaTeX. -

Leonhard Euler English Version

LEONHARD EULER (April 15, 1707 – September 18, 1783) by HEINZ KLAUS STRICK , Germany Without a doubt, LEONHARD EULER was the most productive mathematician of all time. He wrote numerous books and countless articles covering a vast range of topics in pure and applied mathematics, physics, astronomy, geodesy, cartography, music, and shipbuilding – in Latin, French, Russian, and German. It is not only that he produced an enormous body of work; with unbelievable creativity, he brought innovative ideas to every topic on which he wrote and indeed opened up several new areas of mathematics. Pictured on the Swiss postage stamp of 2007 next to the polyhedron from DÜRER ’s Melencolia and EULER ’s polyhedral formula is a portrait of EULER from the year 1753, in which one can see that he was already suffering from eye problems at a relatively young age. EULER was born in Basel, the son of a pastor in the Reformed Church. His mother also came from a family of pastors. Since the local school was unable to provide an education commensurate with his son’s abilities, EULER ’s father took over the boy’s education. At the age of 14, EULER entered the University of Basel, where he studied philosophy. He completed his studies with a thesis comparing the philosophies of DESCARTES and NEWTON . At 16, at his father’s wish, he took up theological studies, but he switched to mathematics after JOHANN BERNOULLI , a friend of his father’s, convinced the latter that LEONHARD possessed an extraordinary mathematical talent. At 19, EULER won second prize in a competition sponsored by the French Academy of Sciences with a contribution on the question of the optimal placement of a ship’s masts (first prize was awarded to PIERRE BOUGUER , participant in an expedition of LA CONDAMINE to South America). -

Math 63: Winter 2021 Lecture 17

Math 63: Winter 2021 Lecture 17 Dana P. Williams Dartmouth College Monday, February 15, 2021 Dana P. Williams Math 63: Winter 2021 Lecture 17 Getting Started 1 We should be recording. 2 Remember it is better for me if you have your video on so that I don't feel I'm just talking to myself. 3 Our midterm will be available Friday after class and due Sunday by 10pm. It will cover through Today's lecture. More details soon. 4 Time for some questions! Dana P. Williams Math 63: Winter 2021 Lecture 17 Rules To Differentiate With The following are routine consequences of the definition. Lemma If f (x) = c for all x 2 R, then f 0(x) = 0 for all x 2 R. If f (x) = x for all x 2 R, then f 0(x) = 1 for all x 2 R. Theorem Suppose that f and g are differentiable at x0. Then so are f ± g, f fg, and if g(x0) 6= 0, g . Futhermore, 0 0 0 1 (f ± g) (x0) = f (x0) ± g (x0), 0 0 0 2 (fg) (x0) = f (x0)g(x0) + f (x0)g (x0), and 0 f 0(x )g(x )−f (x )g 0(x ) 3 f 0 0 0 0 (x0) = 2 . g g(x0) Dana P. Williams Math 63: Winter 2021 Lecture 17 More Formulas Corollary Suppose that f is differentiable at x0 and c 2 R. Then cf is 0 0 differentiable at x0 and (cf ) (x0) = cf (x0). Corollary Suppose that n 2 Z and f (x) = xn. -

Summation of Divergent Power Series by Means of Factorial Series

Summation of divergent power series by means of factorial series Ernst Joachim Weniger Institut f¨ur Physikalische und Theoretische Chemie, Universit¨at Regensburg, D-93040 Regensburg, Germany Abstract Factorial series played a major role in Stirling’s classic book Methodus Differentialis (1730), but now only a few specialists still use them. This article wants to show that this neglect is unjustified, and that factorial series are useful numerical tools for the summation of divergent (inverse) power series. This is documented by summing the divergent asymptotic expansion for the exponential integral E1(z) and the factorially divergent Rayleigh-Schr¨odinger perturba- tion expansion for the quartic anharmonic oscillator. Stirling numbers play a key role since they occur as coefficients in expansions of an inverse power in terms of inverse Pochhammer symbols and vice versa. It is shown that the relationships involving Stirling numbers are special cases of more general orthogonal and triangular transformations. Keywords: Factorial series; Divergent asymptotic (inverse) power series; Stieltjes series; Quartic anharmonic oscillator; Stirling numbers; General orthogonal and triangular transformations; 2010 MSC: 11B73; 40A05; 40G99; 81Q15; 1. Introduction Power series are extremely important analytical tools not only in mathematics, but also in the mathematical treat- ment of scientific and engineering problems. Unfortunately, a power series representation for a given function is from a numerical point of view a mixed blessing. A power series converges within its circle of convergence and diverges outside. Circles of convergence normally have finite radii, but there are many series expansions of consider- able practical relevance, for example asymptotic expansions for special functions or quantum mechanical perturbation expansions, whose circles of convergence shrink to a single point. -

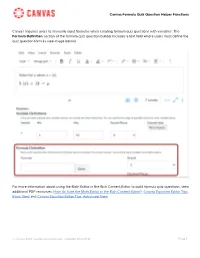

Canvas Formula Quiz Question Helper Functions Canvas Requires Users to Manually Input Formulas When Creating Formula Quiz Ques

Canvas Formula Quiz Question Helper Functions Canvas requires users to manually input formulas when creating formula quiz questions with variables. The Formula Definition section of the formula quiz question builder includes a text field where users must define the quiz question formula (see image below). For more information about using the Math Editor in the Rich Content Editor to build formula quiz questions, view additional PDF resources: How do I use the Math Editor in the Rich Content Editor?, Canvas Equation Editor Tips: Basic View and Canvas Equation Editor Tips: Advanced View. © Canvas 2021 | guides.canvaslms.com | updated 2021-01-16 Page 1 Canvas Formula Quiz Question Helper Functions Helper Functions Use the helper functions listed below to build formulas in the Formula Definition section of the Formula question quiz question creator. Notes: ● All functions accept only numeric parameters. ● All trigonometric function calculations are performed in radians. To convert to or from degrees, use the deg_to_rad( ) or rad_to_deg( ) functions. ● The Formula Definition text field does not designate definable variables with square brackets. ● Variables must start with a letter and may be followed by any combination of letters and numbers. Keep in mind that variable names are case sensitive and characters other than letters and numbers are not recognized. ● In the Formula Definition text field, Canvas translates the entry of the letter “e” as the constant e. ● Helper functions can be nested. For an example of nested helper functions, see the entry for At in the table below. ● Several functions operate on a list of numbers. Unless otherwise noted, the list parameter is defined with a comma-separated list of values or with a nested reverse( ) or sort( ) function. -

Degenerate Bernoulli Polynomials, Generalized Factorial Sums, and Their Applications

Journal of Number Theory 128 (2008) 738–758 www.elsevier.com/locate/jnt Degenerate Bernoulli polynomials, generalized factorial sums, and their applications Paul Thomas Young Department of Mathematics, College of Charleston, Charleston, SC 29424, USA Received 14 August 2006; revised 24 January 2007 Available online 7 May 2007 Communicated by David Goss Abstract We prove a general symmetric identity involving the degenerate Bernoulli polynomials and sums of generalized falling factorials, which unifies several known identities for Bernoulli and degenerate Bernoulli numbers and polynomials. We use this identity to describe some combinatorial relations between these poly- nomials and generalized factorial sums. As further applications we derive several identities, recurrences, and congruences involving the Bernoulli numbers, degenerate Bernoulli numbers, generalized factorial sums, Stirling numbers of the first kind, Bernoulli numbers of higher order, and Bernoulli numbers of the second kind. © 2007 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Keywords: Bernoulli numbers; Degenerate Bernoulli numbers; Power sum polynomials; Generalized factorials; Stirling numbers of first kind; Bernoulli numbers of second kind 1. Introduction Carlitz [3,4] defined the degenerate Bernoulli polynomials βm(λ, x) for λ = 0 by means of the generating function ∞ t tm (1 + λt)μx = β (λ, x) (1.1) (1 + λt)μ − 1 m m! m=0 E-mail address: [email protected]. 0022-314X/$ – see front matter © 2007 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.jnt.2007.02.007 P.T. Young / Journal of Number Theory 128 (2008) 738–758 739 where λμ = 1. These are polynomials in λ and x with rational coefficients; we often write βm(λ) for βm(λ, 0), and refer to the polynomial βm(λ) as a degenerate Bernoulli number. -

Handout 2: Lambda Calculus Examples

06-02552 Principles of Programming Languages The University of Birmingham Spring Semester 2009-10 School of Computer Science c Uday Reddy2009-10 Handout 2: Lambda Calculus Examples In this handout, we look at several examples of lambda terms in order to provide a flavour of what is possible with the lambda calculus. 1 Notations For convenience, we often give names to the lambda terms we examine. These names will be either written in bold (such as name) or underlines (such as name). Note that these names are not part of the lambda calculus itself. They are external. We also feel free to use these names in other lambda terms. In that situation, we should think of the names as standing in for the lambda terms that they name. Even though the lambda calculus is untyped, a large majority of the lambda terms that we look at can be given types. In fact, looking at the types of the terms provides insight into the kind of functions these terms represent. So, wherever possible, we mention the types of the functions. We use capital letters A, B, . to represent arbitrary types and the → symbol to represent function types. For example, A → B represents the type of functions from A to B, i.e., functions that given A-typed arguments, return B-typed results. We use a bracketing convention to parse type expressions with multiple → symbols: A type expression of the form A1 → A2 → · · · An → B means A1 → (A2 → · · · (An → B) ···). We say that the → operator associates to the right. 2 Examples 1. -

Evaluation of Interaction Effects in Two-Factorial Designs By

Evaluation of interaction effects in two-factorial designs by simultaneous confidence intervals in the cell means model Von der Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Universität Hannover zur Erlangung des Grades Doktor der Naturwissenschaften – Dr.rer.nat. – genehmigte Dissertation von M.Sc. Andreas Kitsche geboren am 10.02.1986 in Zerbst 2014 Referent: Prof. Dr. Ludwig A. Hothorn Korreferent: Prof. Dr. Hans-Peter Piepho Tag der Promotion: 06.02.2014 Kurzzusammenfassung In den Biowissenschaften werden häufig Experimente mit zwei oder mehr Einflussfaktoren durchgeführt. Im Gegensatz zu einfaktoriellen Versuchen ermöglichen solche Anlagen so- wohl die Analyse der Haupteffekte der einzelnen Einflussfaktoren, als auch einer etwaigen Interaktion zwischen den Faktoren. Dabei bezeichnet eine Interaktion im statistischen Sinne die unterschiedliche Ausprägung des Effektes eines Faktors über die Stufen eines an- deren Faktors. In der klassischen Datenanalyse werden solche Interaktionen mittels einer Varianzanalyse und den korrespondierenden F-Tests ausgewertet. Ein Nachteil dieser Auswertung ist, dass der F-Test nur eine globale Testentscheidung zur Verfügung stellt. Häufig ist der Wissenschaftler jedoch daran interessiert auf welchen Faktorstufen die In- teraktion beruht. In dieser Arbeit wird die Formulierung von geeigneten Hypothesen für eine tiefgründigere Analyse der Interaktionseffekte dargestellt. Dabei werden die Hypothesen als Kontraste von Mittelwertsdifferenzen formuliert. Eine weitere Möglichkeit geeignete Hypothesen