Anticipated Acquisition by Firstgroup PLC of the Greater Western Passenger Rail Franchise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Railfuture Response to Consultations on the Proposed East Coast Main Line Timetable May 2022

RAILFUTURE RESPONSE TO CONSULTATIONS ON THE PROPOSED EAST COAST MAIN LINE TIMETABLE MAY 2022 From: Railfuture Passenger Group & Branches: East Anglia, East Midlands, Lincolnshire, London & South East, North East, North West, Yorkshire & Scotland Submitted to: CrossCountry, Great Northern/Thameslink, LNER, Northern, TransPennine Express Copied to: East Midlands Railway, First East Coast Trains, Grand Central, Hull Trains, Network Rail & ScotRail Index Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 Background ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 Executive Summary....................................................................................................................................... 2 Strategic Interventions .................................................................................................................................. 3 LNER ............................................................................................................................................................... 5 Responses to LNER Questionnaire ............................................................................................ 6 TransPennine Express .................................................................................................................................. 9 CrossCountry ............................................................................................................................................... -

North West Region Cheshire and North Wales

NATIONS, REGIONS & GROUPS NORTH WEST REGION LONDON REGION CHESHIRE AND NORTH WALES GROUPS HEATHROW GROUP Borderlands (Wrexham to Bidston) rail line Crossrail becomes Elizabeth Line full house greeted speaker John Goldsmith, Community A Relations Manager for Crossrail. Some 43km of new tunnelling is now complete under central London, and 65 million tonnes of material have been excavated. Building work on the whole line is now 87% complete. The first trains of the new Elizabeth Line are now in service between Liverpool Street and Shenfield where a new platform has been built for them, and the roof garden at the seven-storey Canary Wharf station has been open for some time. The 70 trains, built in Derby by Bombardier, are some 10–15% lighter than those now in use and will be in nine-car sets, 200m long, seating 450 passengers, with an estimated total capacity including standing passengers of 1,500 at peak times, most of The Borderlands line runs from Wrexham Central Station to Bidston Station whom are expected to be short-journey passengers. Seats will be sideways, forward facing and backward facing, giving plenty of his event was held in the strategic location of Chester, circulating space. The early trains now in service between T close to the border between England and Wales. The Liverpool Street and Shenfield are only seven cars long, because location chosen was apt, as the Borderlands line is a key the main line platforms at Liverpool Street will not accept nine-car strategic passenger route between North Wales and Merseyside. trains, but this is an interim measure until the lower level new John Allcock, Chairman, Wrexham–Bidston Rail Users’ Association station is operative. -

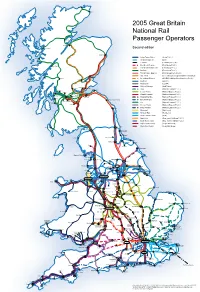

2005 Great Britain National Rail Passenger Operators

Thurso Wick 2005 Great Britain National Rail Dingwall Passenger Operators Inverness Kyle of Lochalsh Second edition Aberdeen Arriva Trains Wales (Arriva P.L.C.) Mallaig Heathrow Express (BAA) Eurostar (Eurostar (U.K.) Ltd.) First Great Western (First Group P.L.C.) Fort William First Great Western Link (First Group P.L.C.) ScotRail (First Group P.L.C.) TransPennine Express (First Group P.L.C./Keolis) Hull Trains (G.B. Railways Group/Renaissance Railways) Dundee Oban Crianlarich Great North Eastern (G.N.E.R. Holdings/Sea Containers P.L.C.) Perth Southern (GOVIA) Thameslink (GOVIA) Chiltern Railways (M40 Trains) Cardenden Stirling Kirkcaldy North Berwick ‘One’ (National Express P.L.C.) Balloch Gourock Milngavie Central Trains (National Express P.L.C.) Cumbernauld Gatwick Express (National Express P.L.C.) Bathgate Wemyss Bay Glasgow Drumgelloch Edinburgh Midland Mainline (National Express P.L.C.) Largs Berwick upon Tweed Silverlink Trains (National Express P.L.C.) Neilston East Kilbride Carstairs Ardrossan c2c (National Express P.L.C.) Harbour Lanark Wessex Trains (National Express P.L.C.) Chathill Wagn Railway (National Express P.L.C.) Merseyrail (Ned-Serco) Northern Rail (Ned-Serco) South Eastern Trains (SRA) Island Line (Stagecoach Holdings P.L.C.) South West Trains (Stagecoach Holdings P.L.C.) Virgin CrossCountry (Virgin Rail Group) Newcastle Virgin West Coast (Virgin Rail Group) Stranraer Carlisle Sunderland Hartlepool Bishop Auckland Workington Saltburn Darlington Middlesbrough Whitby Windermere Battersby Scarborough Barrow-in-Furness -

Firstgroup Plc Annual Report and Accounts 2015 Contents

FirstGroup plc Annual Report and Accounts 2015 Contents Strategic report Summary of the year and financial highlights 02 Chairman’s statement 04 Group overview 06 Chief Executive’s strategic review 08 The world we live in 10 Business model 12 Strategic objectives 14 Key performance indicators 16 Business review 20 Corporate responsibility 40 Principal risks and uncertainties 44 Operating and financial review 50 Governance Board of Directors 56 Corporate governance report 58 Directors’ remuneration report 76 Other statutory information 101 Financial statements Consolidated income statement 106 Consolidated statement of comprehensive income 107 Consolidated balance sheet 108 Consolidated statement of changes in equity 109 Consolidated cash flow statement 110 Notes to the consolidated financial statements 111 Independent auditor’s report 160 Group financial summary 164 Company balance sheet 165 Notes to the Company financial statements 166 Shareholder information 174 Financial calendar 175 Glossary 176 FirstGroup plc is the leading transport operator in the UK and North America. With approximately £6 billion in revenues and around 110,000 employees, we transported around 2.4 billion passengers last year. In this Annual Report for the year to 31 March 2015 we review our performance and plans in line with our strategic objectives, focusing on the progress we have made with our multi-year transformation programme, which will deliver sustainable improvements in shareholder value. FirstGroup Annual Report and Accounts 2015 01 Summary of the year and -

Rail Station Usage in Wales, 2018-19

Rail station usage in Wales, 2018-19 19 February 2020 SB 5/2020 About this bulletin Summary This bulletin reports on There was a 9.4 per cent increase in the number of station entries and exits the usage of rail stations in Wales in 2018-19 compared with the previous year, the largest year on in Wales. Information year percentage increase since 2007-08. (Table 1). covers stations in Wales from 2004-05 to 2018-19 A number of factors are likely to have contributed to this increase. During this and the UK for 2018-19. period the Wales and Borders rail franchise changed from Arriva Trains The bulletin is based on Wales to Transport for Wales (TfW), although TfW did not make any the annual station usage significant timetable changes until after 2018-19. report published by the Most of the largest increases in 2018-19 occurred in South East Wales, Office of Rail and Road especially on the City Line in Cardiff, and at stations on the Valleys Line close (ORR). This report to or in Cardiff. Between the year ending March 2018 and March 2019, the includes a spreadsheet level of employment in Cardiff increased by over 13,000 people. which gives estimated The number of station entries and exits in Wales has risen every year since station entries and station 2004-05, and by 75 per cent over that period. exits based on ticket sales for each station on Cardiff Central remains the busiest station in Wales with 25 per cent of all the UK rail network. -

Issue 15 15 July 2005 Contents

RailwayThe Herald 15 July 2005 No.15 TheThe complimentarycomplimentary UKUK railway railway journaljournal forfor thethe railwayrailway enthusiastenthusiast In This Issue Silverlink launch Class 350 ‘Desiro’ New Track Machine for Network Rail Hull Trains names second ‘Pioneer’ plus Notable Workings and more! RailwayThe Herald Issue 15 15 July 2005 Contents Editor’s comment Newsdesk 3 Welcome to this weeks issue of All the latest news from around the UK network. Including launch of Class 350 Railway Herald. Despite the fact ‘Desiro’ EMUs on Silverlink, Hull Trains names second Class 222 unit and that the physical number of Ribblehead Viaduct memorial is refurbished. locomotives on the National Network continues to reduce, the variety of movements and operations Rolling Stock News 6 that occur each week is quite A brand new section of Railway Herald, dedicated to news and information on the astounding, as our Notable Workings UK Rolling Stock scene. Included this issue are details of Network Rail’s new column shows. Dynamic Track Stablizer, which is now being commissioned. The new look Herald continues to receive praise from readers across the globe - thank you! Please do feel free to pass the journal on to any friends or Notable Workings 7 colleagues who you think would be Areview of some of the more notable, newsworthy and rare workings from the past week interested. All of our back-issues are across the UK rail network. available from the website. We always enjoy hearing from readers on their opinions about the Charter Workings 11 journal as well as the magazine. The Part of our popular ‘Notable Workings’ section now has its own column! Charter aim with Railway Herald still Workings will be a regular part of Railway Herald, providing details of the charters remains to publish the journal which have worked during the period covered by this issue and the motive power. -

Competitive Tendering of Rail Services EUROPEAN CONFERENCE of MINISTERS of TRANSPORT (ECMT)

Competitive EUROPEAN CONFERENCE OF MINISTERS OF TRANSPORT Tendering of Rail Competitive tendering Services provides a way to introduce Competitive competition to railways whilst preserving an integrated network of services. It has been used for freight Tendering railways in some countries but is particularly attractive for passenger networks when subsidised services make competition of Rail between trains serving the same routes difficult or impossible to organise. Services Governments promote competition in railways to Competitive Tendering reduce costs, not least to the tax payer, and to improve levels of service to customers. Concessions are also designed to bring much needed private capital into the rail industry. The success of competitive tendering in achieving these outcomes depends critically on the way risks are assigned between the government and private train operators. It also depends on the transparency and durability of the regulatory framework established to protect both the public interest and the interests of concession holders, and on the incentives created by franchise agreements. This report examines experience to date from around the world in competitively tendering rail services. It seeks to draw lessons for effective design of concessions and regulation from both of the successful and less successful cases examined. The work RailServices is based on detailed examinations by leading experts of the experience of passenger rail concessions in the United Kingdom, Australia, Germany, Sweden and the Netherlands. It also -

Class 150/2 Diesel Multiple Unit

Class 150/2 Diesel Multiple Unit Contents How to install ................................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Technical information ................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Liveries .............................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Cab guide ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 15 Keyboard controls ...................................................................................................................................................................... 16 Features .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 17 Global System for Mobile Communication-Railway (GSM-R) ............................................................................. 18 Registering .......................................................................................................................................................................... 18 Deregistering - Method 1 ............................................................................................................................................ -

2009-041 Crosscountry Spanner Awards

Press Release 04 December 2009 XC2009/041 (LW) CROSSCOUNTRY TOPS RAILWAY CHARTS It’s Gold and Silver for award-winning train operator CrossCountry has won two prestigious rail industry awards in recognition of its trains being one of the most improved and reliable fleets across Britain’s rail network. CrossCountry was awarded Gold and Silver at last week’s annual ‘Golden Spanner’ ceremony organised by industry magazine Modern Railways. The Golden Spanner went to the Class 221 Super Voyagers for taking first place in the ‘Modern DMU’ category as the most reliable fleet in its class. The Super Voyagers also took the Silver Spanner for being the most improved fleet thanks to reliability being up 118% on last year. The ‘Golden Spanner’ is an awards scheme aimed at promoting excellence in train maintenance within Britain. Sarah Kendall, Production Director at CrossCountry said: “We are extremely proud to win these nationally recognised awards. Since the start of our franchise in November 2007 the team at CrossCountry has worked very closely with Bombardier Transportation, our maintainer to take specific targeted steps to improve the reliability of our Voyager trains. Our focus now is to build on this significant progress and further improve our performance. Train reliability is vital for our customers and therefore of the highest priority for us.” All trains are ranked on the distance they cover between technical faults by the Association of Train Operating Companies’ (ATOC) National Fleet Reliability Improvement Programme. Using this league table (see below) CrossCountry’s Voyager trains outperformed all other intercity fleets across the country. -

Wales Network Specification: March 2017 Network Rail – Network Specification: Wales 02 Wales

Delivering a better railway for a better Britain Network Specification 2017 Wales Network Specification: March 2017 Network Rail – Network Specification: Wales 02 Wales Incorporating Strategic Routes: L: Wales and This Network Specification describes the Wales Route in its There are also a number of other supporting documents that Borders geographical context and provides a summary of the infrastructure present specific strategies including: that is available for passenger and freight operators. It identifies Scenarios and Long Distance Forecasts – published in June 2009. the key markets for passenger and freight services by Strategic • The document considers how demand for long distance rail Route Sections (SRS). The SRSs cover specific sections of the route services, both passenger and freight, might be impacted by four and are published as appendices to this document. They describe in alternative future scenarios greater detail the current and future requirements of each SRS to inform both internal and external stakeholders of our future • Electrification Strategy – published October 2009 presents a strategy. strategy for further electrification of the network. Work is ongoing to refresh the Strategy in the light of committed Control This Network Specification draws upon the supporting evidence Period 5 electrification schemes, the ‘Electric Spine’ development from the Route Utilisation Strategy (RUS) process which informs the project and the formation of a ‘Task Force’ to consider further strategy to 2019, and the emerging findings from the Long Term electrification opportunities across the North of England. Planning Process (LTPP) which looks ahead 10 and 30 years. Stations – published in August 2011. This strategy considered the As part of the LTPP, four Market Studies have been established, • pedestrian capacity of stations on the network. -

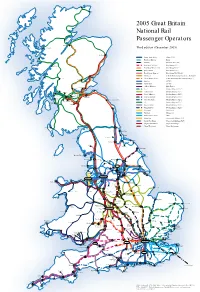

2005 Great Britain National Rail Passenger Operators Dingwall

Thurso Wick 2005 Great Britain National Rail Passenger Operators Dingwall Inverness Kyle of Lochalsh Third edition (December 2005) Aberdeen Arriva Trains Wales (Arriva P.L.C.) Mallaig Heathrow Express (BAA) Eurostar (Eurostar (U.K.) Ltd.) First Great Western (First Group P.L.C.) Fort William First Great Western Link (First Group P.L.C.) First ScotRail (First Group P.L.C.) TransPennine Express (First Group P.L.C./Keolis) Hull Trains (G.B. Railways Group/Renaissance Railways) Dundee Oban Crianlarich Great North Eastern (G.N.E.R. Holdings/Sea Containers P.L.C.) Perth Southern (GOVIA) Thameslink (GOVIA) Chiltern Railways (M40 Trains) Cardenden Stirling Kirkcaldy ‘One’ (National Express P.L.C.) North Berwick Balloch Central Trains (National Express P.L.C.) Gourock Milngavie Cumbernauld Gatwick Express (National Express P.L.C.) Bathgate Wemyss Bay Glasgow Drumgelloch Edinburgh Midland Mainline (National Express P.L.C.) Largs Berwick upon Tweed Silverlink Trains (National Express P.L.C.) Neilston East Kilbride Carstairs Ardrossan c2c (National Express P.L.C.) Harbour Lanark Wessex Trains (National Express P.L.C.) Chathill Wagn Railway (National Express P.L.C.) Merseyrail (Ned-Serco) Northern (Ned-Serco) South Eastern Trains (SRA) Island Line (Stagecoach Holdings P.L.C.) South West Trains (Stagecoach Holdings P.L.C.) Virgin CrossCountry (Virgin Rail Group) Virgin West Coast (Virgin Rail Group) Newcastle Stranraer Carlisle Sunderland Hartlepool Bishop Auckland Workington Saltburn Darlington Middlesbrough Whitby Windermere Battersby Scarborough -

Crossrail Environmental Statement 8A

Crossrail Environmental Statement Volume 8a Appendices Transport assessment: methodology and principal findings 8a If you would like information about Crossrail in your language, please contact Crossrail supplying your name and postal address and please state the language or format that you require. To request information about Crossrail contact details: in large print, Braille or audio cassette, Crossrail FREEPOST NAT6945 please contact Crossrail. London SW1H0BR Email: [email protected] Helpdesk: 0845 602 3813 (24-hours, 7-days a week) Crossrail Environmental Statement Volume 8A – Appendices Transport Assessment: Methodology and Principal Findings February 2005 This volume of the Transport Assessment Report is produced by Mott MacDonald – responsible for assessment of temporary impacts for the Central and Eastern route sections and for editing and co-ordination; Halcrow – responsible for assessment of permanent impacts route-wide; Scott Wilson – responsible for assessment of temporary impacts for the Western route section; and Faber Maunsell – responsible for assessment of temporary and permanent impacts in the Tottenham Court Road East station area, … working with the Crossrail Planning Team. Mott MacDonald St Anne House, 20–26 Wellesley Road, Croydon, Surrey CR9 2UL, United Kingdom www.mottmac.com Halcrow Group Limited Vineyard House, 44 Brook Green, Hammersmith, London W6 7BY, United Kingdom www.halcrow.com Scott Wilson 8 Greencoat Place, London SW1P 1PL, United Kingdom This document has been prepared for the titled project or named part thereof and should not be relied upon or used for any other project without an independent check being carried out as to its suitability and prior written authority of Mott MacDonald, Halcrow, Scott www.scottwilson.com Wilson and Faber Maunsell being obtained.