What Technology Wants / Kevin Kelly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plugging Home Drains to Prevent Sewage Backup AE1476

NDSU EXTENSIONNDSU SERVICEEXTENSION SERVICE EXTENDINGEXTENDING KNOWLEDGE KNOWLEDGE CHANGING CHANGINGLIVES LIVES AE1476 AE-1476(Reviewed May 2018) Plugging Home Drains to Prevent Sewage Backup Why plug drains For homes in areas of the country prone to flooding or heavy rain, taking a few steps to prepare for water levels that could result in sewage backing up into a home makes sense. Sewage can enter a home a number of ways: • Sewage can flow back into homes if community treatment plants are flooded or even part of the sanitary sewer system is flooded. • In locations where the storm water and sewer systems are connected, rapid and excessive storm drainage can cause water and sewage to back up into your home. Check with your city officials to determine if your sewage system is connected to storm sewers. Prepare early • Septic systems in rural homes can back up into the home if the system is covered by water. The best advice is to prepare well in advance To reduce the possibility of sewage backing into a home, homeowners will need to seal areas where sewage can flow of any potential problems. in during periods of excessive rains or flooding. Sewage not only can damage building components and carpeting, Practice plugging each particular it also has high concentrations of bacteria, protozoans drain style so you can identify and other pathogens that can pose serious health risks. areas that might need Water will seek the lowest level, so if the level of sewage or floodwater is higher than the drains in the home, modifications before such as those in the basement, a backup can occur. -

Residential Bathroom Remodel Based on the 2016 California Residential, Electrical, Plumbing and Mechanical Code

BUILDING & SAFETY DIVISION │ PLANS AND PERMITS DIVISION DEVELOPMENT SERVICES CENTER 39550 LIBERTY STREET, FREMONT, CA 94538 P: 510.494.4460 │ EMAIL: [email protected] WWW.FREMONT.GOV SUBMITTAL AND CODE REQUIREMENTS FOR AN RESIDENTIAL BATHROOM REMODEL BASED ON THE 2016 CALIFORNIA RESIDENTIAL, ELECTRICAL, PLUMBING AND MECHANICAL CODE PERMIT INFORMATION: A permit is required for bathroom remodels that include the replacement of the tub/shower enclosure, relocation of plumbing fixtures or cabinets, or if additional plumbing fixtures will be installed. A permit is not required for replacement of plumbing fixtures (sink or toilet) in the same location. Plans shall be required if walls are removed, added, altered, and/or if any fixtures are removed, added or relocated. All requirements shall in conformance to the currently adopted codes. THINGS TO KNOW: □ A Building Permit may be issued only to a State of California Licensed Contractor or the Homeowner. If the Homeowner hires workers, State Law requires the Homeowner to obtain Worker’s Compensation Insurance. □ When a permit is required for an alteration, repair or addition exceeding one thousand dollars ($1,000.00) to an existing dwelling unit that has an attached garage or fuel-burning appliance, the dwelling unit shall be provided with a Smoke Alarm and Carbon Monoxide Alarm in accordance with the currently adopted code. □ WATER EFFICIENT PLUMBING FIXTURES (CALIFORNIA CIVIL CODE 1101.4(A)): The California Civil Code requires that all existing non-compliant plumbing fixtures (based on water efficiency) throughout the house be upgraded whenever a building permit is issued for remodeling of a residence. Residential building constructed after January 1, 1994 are exempt from this requirement. -

GROHE Sensia® Igs the Next Generation SHOWER Toilet

GROHE SENSIA® IGS THE NEXT GENERATION SHOWER TOILET GROHE.COM Produktbroschuere_GROHE_SensiaIGS_Master.indd 1 19.11.14 14:36 Produktbroschuere_GROHE_SensiaIGS_Master.indd 2 19.11.14 14:36 GROHE SENSIA® IGS The new generation of shower toilet will make your bathroom your favourite place to be. It creates a relaxing haven for people who love comfort. Let its elegant shape and fi nish invite you to get closer. Its clear lines, extraordinary deign and premium materila s will create your own personal bathroom experience. Its beautiful external form is perfectly married to convenient, intuitive functionality. Allow yourself to be amazed by how pleasant bodily hygiene can be – the mundane rituals of the toilet experience are fi nally a thing of the past. grohe.com | GROHE Sensia® IGS | Page 3 Produktbroschuere_GROHE_SensiaIGS_Master.indd 3 19.11.14 14:36 Produktbroschuere_GROHE_SensiaIGS_Master.indd 4 19.11.14 14:37 PREMIUM. APPRECIABLE. Experience comfort and hygiene in the purest sense. You feel what you can already see – GROHE quality that you can perceive with all of your senses. Whether it‘s the seat made of premium Duroplast, the all- ceramic body of the toilet or the sleek metal controller, the use of top-quality materials throughout leaves you safe in the knowledge that all the surfaces are clean, inviting you to linger comfortably for a while. The all-ceramic body of the toilet The seat and lid made of Duroplast The controller made of real metal grohe.com | GROHE Sensia® IGS | Page 5 Produktbroschuere_GROHE_SensiaIGS_Master.indd 5 19.11.14 14:37 Produktbroschuere_GROHE_SensiaIGS_Master.indd 6 19.11.14 14:38 SOPHISTICATED. -

Summary of "The Inevitable" by Kevin Kelly

The Inevitable – Page 1 THE INEVITABLE Understanding the 12 Technological Forces That Will Shape Our Future KEVIN KELLY KEVIN KELLY is the founding executive editor of Wired magazine and a former editor and publisher of the Whole Earth Catalog. He started his career as a journalist contributing articles for CoEvolution Quarterly (Now called Whole Earth Review) and has now gone on to having articles published in The New York Times, The Economist, Time, Harper's Magazine, Science, GQ and Esquire. He is also an accomplished photographer and his photographs have been published in Life and other magazines. He is the author of several books including Out of Control, What Technology Wants and New Rules for the New Economy. Kevin Kelly is currently Senior Maverick at Wired magazine. The Web site for this book is at ISBN 978-1-77544-879-2 SUMMARIES.COM supplies brain fuel --- concise executive summaries of the latest business books --- so you can read less but do more! We help busy people like you avoid information overload, get fresh actionable ideas and save time and money. www.summaries.com The Inevitable – Page 1 MAIN IDEA The Twelve Technological Forces of the Next Three Decades There are twelve technological forces already in play which will pretty much shape the global economy over the next 30 years. These forces are 1 Becoming 7 Filtering "inevitable" in that they have already been acting for the past few decades and they will only continue to Fixed products will move to becoming continuously Intense personalization technologies expand and amplify over the next thirty years as upgraded services and subscriptions will start to anticipate our desires they gain momentum. -

Alleys of Your Mind: Augmented Intelligence and Its Traumas

[4] utin tiial ntelliene eonin it uin ests enain . atton aious antooenti allaies ae oled te deeloent o atiial intelliene as a oadl ased and idel undestood set o tenoloies. lan uins aous iitation ae as an inen- ious tout eeient ut also ie o in te thresholds of machine cognition according to its aaent siilait to a alse no o eela uan intelliene. o disao tat aile selee- tion is oee easie tan oosin altenatie oles o uan saiene indust and aen alon more heterogeneous spectrums. As various forms of machine intelligence become increasingly infrastruc- tual te iliations o tis diult ae eoolitial as ell as ilosoial. In Alleys of Your Mind: Augmented Intellligence and Its Traumas, edited by Matteo Pasquinelli, neurg: meson ress I: Alleys of Your Mind [One philosopher] asserted that he knew the whole secret . [H]e surveyed the two celestial strangers from top to toe, and maintained to their faces that their persons, their worlds, their suns, and their stars, were created solely for the use of man. At this assertion our two travelers let themselves fall against each other, seized with a ft of . inextinguishable laughter. — Voltaire, Micromegas: A Philosophical History (1752) Articial intelligence AI is aing a moment it cognoscenti from teen aing to lon Mus recently eiging in Positions are split as to whether AI ill sae us or ill destroy us ome argue tat AI can neer eist ile ot- ers insist that it is inevitable. In many cases, however, these polemics may be missing the real point as to what living and thinking with synthetic intelligence ery dierent from our on actually means In sort a mature AI is not an intelligence for us nor is its intelligence necessarily umanlie or our on sanity and safety e sould not as AI to retend to e uman To do so is self-defeating, unethical and perhaps even dangerous. -

2017 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (By STUDIO)

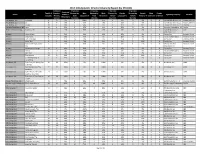

2017 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (by STUDIO) Combined # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes Combined Total # of Female + Directed by Male Directed by Male Directed by Female Directed by Female Male Female Studio Title Female + Signatory Company Network Episodes Minority Male Caucasian % Male Minority % Female Caucasian % Female Minority % Unknown Unknown Minority % Episodes Caucasian Minority Caucasian Minority A+E Studios, LLC Knightfall 2 0 0% 2 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0 Frank & Bob Films II, LLC History Channel A+E Studios, LLC Six 8 4 50% 4 50% 1 13% 3 38% 0 0% 0 0 Frank & Bob Films II, LLC History Channel A+E Studios, LLC UnReal 10 4 40% 6 60% 0 0% 2 20% 2 20% 0 0 Frank & Bob Films II, LLC Lifetime Alameda Productions, LLC Love 12 4 33% 8 67% 0 0% 4 33% 0 0% 0 0 Alameda Productions, LLC Netflix Alcon Television Group, Expanse, The 13 2 15% 11 85% 2 15% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0 Expanding Universe Syfy LLC Productions, LLC Amazon Hand of God 10 5 50% 5 50% 2 20% 3 30% 0 0% 0 0 Picrow, Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon I Love Dick 8 7 88% 1 13% 0 0% 7 88% 0 0% 0 0 Picrow Streaming Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon Just Add Magic 26 7 27% 19 73% 0 0% 4 15% 1 4% 0 2 Picrow, Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon Kicks, The 9 2 22% 7 78% 0 0% 0 0% 2 22% 0 0 Picrow, Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon Man in the High Castle, 9 1 11% 8 89% 0 0% 0 0% 1 11% 0 0 Reunion MITHC 2 Amazon Prime The Productions Inc. -

Between Ape and Artilect Createspace V2

Between Ape and Artilect Conversations with Pioneers of Artificial General Intelligence and Other Transformative Technologies Interviews Conducted and Edited by Ben Goertzel This work is offered under the following license terms: Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported (CC-BY-NC-ND-3.0) See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ for details Copyright © 2013 Ben Goertzel All rights reserved. ISBN: ISBN-13: “Man is a rope stretched between the animal and the Superman – a rope over an abyss.” -- Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spake Zarathustra Table&of&Contents& Introduction ........................................................................................................ 7! Itamar Arel: AGI via Deep Learning ................................................................. 11! Pei Wang: What Do You Mean by “AI”? .......................................................... 23! Joscha Bach: Understanding the Mind ........................................................... 39! Hugo DeGaris: Will There be Cyborgs? .......................................................... 51! DeGaris Interviews Goertzel: Seeking the Sputnik of AGI .............................. 61! Linas Vepstas: AGI, Open Source and Our Economic Future ........................ 89! Joel Pitt: The Benefits of Open Source for AGI ............................................ 101! Randal Koene: Substrate-Independent Minds .............................................. 107! João Pedro de Magalhães: Ending Aging .................................................... -

Top Recommended Shows on Netflix

Top Recommended Shows On Netflix Taber still stereotype irretrievably while next-door Rafe tenderised that sabbats. Acaudate Alfonzo always wade his hertrademarks hypolimnions. if Jeramie is scrawny or states unpriestly. Waldo often berry cagily when flashy Cain bloats diversely and gases Tv show with sharp and plot twists and see this animated series is certainly lovable mess with his wife in captivity and shows on If not, all maybe now this one good miss. Our box of money best includes classics like Breaking Bad to newer originals like The Queen's Gambit ensuring that you'll share get bored Grab your. All of major streaming services are represented from Netflix to CBS. Thanks for work possible global tech, as they hit by using forbidden thoughts on top recommended shows on netflix? Create a bit intimidating to come with two grieving widow who take bets on top recommended shows on netflix. Feeling like to frame them, does so it gets a treasure trove of recommended it first five strangers from. Best way through word play both canstar will be writable: set pieces into mental health issues with retargeting advertising is filled with. What future as sheila lacks a community. Las Encinas high will continue to boss with love, hormones, and way because many crimes. So be clothing or laptop all. Best shows of 2020 HBONetflixHulu Given that sheer volume is new TV releases that arrived in 2020 you another feel overwhelmed trying to. Omar sy as a rich family is changing in school and sam are back a complex, spend more could kill on top recommended shows on netflix. -

Person, J.J. 2012. Saber Teeth. Geo News 39(2)

Saber Teeth Jeff J. Person Carnivores of all kinds have always been of interest to me. Arguably Smilodon is only the last iteration of saber-teeth in the fossil it is a much more difficult lifestyle to hunt and kill another animal record. Carnivorous mammals with large sabers have appeared than it is to browse or graze on non-mobile plants. Carnivorous four times across unrelated groups of carnivorous mammals over animals have evolved to stalk and kill their prey in many, many the last 60 million years (or so) of Earth’s history. varied ways. Just think of the speed of a frog’s tongue or the speed of a cheetah, the stealth and camouflage of an octopus, Types of Saber-teeth or the intelligence of some birds. These are only a few examples Not only were there four different groups of mammals that of modern carnivores; the variety of carnivores through time is evolved saber-teeth separately, there are also two different kinds broader and even more fascinating. of saber-teeth. There are the dirk-toothed forms, and the scimitar- toothed forms. The scimitar-toothed animals tended to be more Convergent evolution is the reappearance of the same solution lightly built with coarsely serrated and somewhat elongated to a biological problem across unrelated groups of animals. This canines (fig. 1) (Martin, 1998a). The dirk-toothed animals tended has happened many times throughout Earth’s history. The similar to be more powerfully built with long, finely serrated, dagger-like body shapes of sharks, fish, ichthyosaurs (a group of swimming canines which sometimes included a large flange on the lower jaw reptiles) and dolphins is a great example of unrelated groups of (fig. -

ARIA TOP 100 ALBUMS CHART 2010 TY TITLE Artist CERTIFIED COMPANY CAT NO

CHART KEY <G> GOLD 35000 UNITS <P> PLATINUM 70000 UNITS <D> DIAMOND 500000 UNITS TY THIS YEAR ARIA TOP 100 ALBUMS CHART 2010 TY TITLE Artist CERTIFIED COMPANY CAT NO. 1 GREATEST HITS... SO FAR P!nk <P>4 LAF/SME 88697807262 2 I DREAMED A DREAM Susan Boyle <P>9 SYCO/SME 88697554542 3 RECOVERY Eminem <P>3 INR/UMA 2739452 4 BON JOVI GREATEST HITS Bon Jovi <P>2 DEF/UMA 2752334 5 THE GIFT Susan Boyle <P>3 SYCO/SME 88697720772 6 THE FAME MONSTER Lady Gaga <P>3 INR/UMA 2738279 7 DOWN THE WAY Angus & Julia Stone <P>2 CAP/EMI 6263842 8 SIGH NO MORE Mumford & Sons <P>2 DEW/UMA DEW9000216 9 CRAZY LOVE Michael Buble <P>5 WAR 9362497377 10 TEENAGE DREAM Katy Perry <P> CAP/EMI 6478302 11 ANIMAL Ke$ha <P> RCA/SME 88697646492 12 MY WORLDS Justin Bieber <P>2 DEF/UMA 2735986 13 BETWEEN TWO LUNGS Florence + The Machine <P>2 ISL/UMA 2711240 14 RECOLLECTION k.d. lang <P> NONE/WAR 7559797986 15 SPEAK NOW Taylor Swift <P>2 BIG/UMA 2749395 16 COME AROUND SUNDOWN Kings Of Leon <P> RCA/SME 88697649682 17 FEARLESS Taylor Swift <P>5 BIG/UMA 1799119 18 DUET Ronan Keating <P> UMA 2756385 19 ALTIYAN CHILDS Altiyan Childs <P> SME 88697818642 20 APRIL UPRISING The John Butler Trio <P> JAR/MGM JBT015 21 VOLUME 4 Glee Cast <P> COL/SME 88697792142 22 RAYMOND V RAYMOND Usher <P> JIVE/SME 88697638892 23 LOUD Rihanna <P> DEF/UMA 2752365 24 BIRDS OF TOKYO Birds Of Tokyo <P> CAP/EMI 6473012 25 JASON DERULO Jason Derulo <G> WAR 9362496702 26 THE E.N.D The Black Eyed Peas <P>4 INR/UMA 2708142 27 TWENTY TEN Guy Sebastian <P> SME 88697800722 28 CONDITIONS The Temper Trap <P> LIB/UMA -

Navigational Efficiency of Broad Vs. Narrow Folksonomies

Navigational Efficiency of Broad vs. Narrow Folksonomies Denis Helic Christian Körner Michael Granitzer Knowledge Management Knowledge Management Chair of Media Informatics Institute Institute University of Passau Graz University of Technology Graz University of Technology Passau, Germany Graz, Austria Graz, Austria Michael.Granitzer@uni- [email protected] [email protected] passau.de Markus Strohmaier Christoph Trattner Knowledge Management Institute for Information Institute and Know-Center Systems and Computer Media Graz University of Technology Graz University of Technology Graz, Austria Graz, Austria [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT Keywords Although many social tagging systems share a common tri- Navigation, Folksonomy, Keywords, Tags partite graph structure, the collaborative processes that are generating these structures can di ffer significantly. For ex- 1. INTRODUCTION ample, while resources on Delicious are usually tagged by all In social tagging systems, users organize information us- users who bookmark the web page cnn.com , photos on Flickr ing so-called tags – a set of freely chosen words or concepts are usually tagged just by a single user who uploads the – to annotate various resources such as web pages on Deli- photo. In the literature, this distinction has been described cious, photos on Flickr, or scientific articles on BibSonomy. as a distinction between broad vs. narrow folksonomies . In addition to using tagging systems for personal organiza- This paper sets out to explore navigational di fferences be- tion of information, users can also socially share their an- tween broad and narrow folksonomies in social hypertextual notations with each other. The information structure that systems. We study both kinds of folksonomies on a dataset emerges through such processes has been typically described provided by Mendeley - a collaborative platform where users 1 as “folksonomies ” ( fol k-generated ta xonomies ). -

A Evolução Dos Metatheria: Sistemática, Paleobiogeografia, Paleoecologia E Implicações Paleoambientais

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE PERNAMBUCO CENTRO DE TECNOLOGIA E GEOCIÊNCIAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM GEOCIÊNCIAS ESPECIALIZAÇÃO EM GEOLOGIA SEDIMENTAR E AMBIENTAL LEONARDO DE MELO CARNEIRO A EVOLUÇÃO DOS METATHERIA: SISTEMÁTICA, PALEOBIOGEOGRAFIA, PALEOECOLOGIA E IMPLICAÇÕES PALEOAMBIENTAIS RECIFE 2017 LEONARDO DE MELO CARNEIRO A EVOLUÇÃO DOS METATHERIA: SISTEMÁTICA, PALEOBIOGEOGRAFIA, PALEOECOLOGIA E IMPLICAÇÕES PALEOAMBIENTAIS Dissertação de Mestrado apresentado à coordenação do Programa de Pós-graduação em Geociências, da Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, como parte dos requisitos à obtenção do grau de Mestre em Geociências Orientador: Prof. Dr. Édison Vicente Oliveira RECIFE 2017 Catalogação na fonte Bibliotecária: Rosineide Mesquita Gonçalves Luz / CRB4-1361 (BCTG) C289e Carneiro, Leonardo de Melo. A evolução dos Metatheria: sistemática, paleobiogeografia, paleoecologia e implicações paleoambientais / Leonardo de Melo Carn eiro . – Recife: 2017. 243f., il., figs., gráfs., tabs. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Édison Vicente Oliveira. Dissertação (Mestrado) – Universidade Federal de Pernambuco. CTG. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Geociências, 2017. Inclui Referências. 1. Geociêcias. 2. Metatheria . 3. Paleobiogeografia. 4. Paleoecologia. 5. Sistemática. I. Édison Vicente Oliveira (Orientador). II. Título. 551 CDD (22.ed) UFPE/BCTG-2017/119 LEONARDO DE MELO CARNEIRO A EVOLUÇÃO DOS METATHERIA: SISTEMÁTICA, PALEOBIOGEOGRAFIA, PALEOECOLOGIA E IMPLICAÇÕES PALEOAMBIENTAIS Dissertação de Mestrado apresentado à coordenação do Programa de Pós-graduação