The Evolution of Complex Societies in Mesoamerica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Olmec, Toltec, and Aztec

Mesoamerican Ancient Civilizations The Olmec, Toltec, and Aztec Olmecs of Teotihuacán -“The People of the Land of Rubber…” -Large stone heads -Art found throughout Mesoamerica Olmec Civilization Origin and Impact n The Olmec civilization was thought to have originated around 1500 BCE. Within the next three centuries of their arrival, the people built their capital at Teotihuacán n This ancient civilization was believed by some historians to be the Mother-culture and base of Mesoamerica. “The city may well be the basic civilization out of which developed such high art centers as those of Maya, Zapotecs, Toltecs, and Totonacs.” – Stirling Cultural Practices n The Olmec people would bind wooden planks to the heads of infants to create longer and flatter skulls. n A game was played with a rubber ball where any part of the body could be used except for hands. Religion and Art n The Olmecs believed that celestial phenomena such as the phases of the moon affected daily life. n They worshipped jaguars, were-jaguars, and sometimes snakes. n Artistic figurines and toys were found, consisting of a jaguar with a tube joining its front and back feet, with clay disks forming an early model of the wheel. n Large carved heads were found that were made from the Olmecs. Olmec Advancements n The Olmecs were the first of the Mesoamerican societies, and the first to cultivate corn. n They built pyramid type structures n The Olmecs were the first of the Mesoamerican civilizations to create a form of the wheel, though it was only used for toys. -

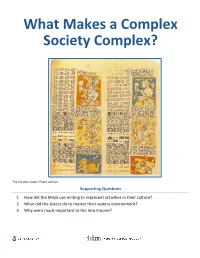

What Makes a Complex Society Complex?

What Makes a Complex Society Complex? The Dresden Codex. Public domain. Supporting Questions 1. How did the Maya use writing to represent activities in their culture? 2. What did the Aztecs do to master their watery environment? 3. Why were roads important to the Inca Empire? Supporting Question 1 Featured Source Source A: Mark Pitts, book exploring Maya writing, Book 1: Writing in Maya Glyphs: Names, Places & Simple Sentences—A Non-Technical Introduction to Maya Glyphs (excerpt), 2008 THE BASICS OF ANCIENT MAYA WRITING Maya writing is composed of various signs and symbol. These signs and symbols are often called ‘hieroglyphs,’ or more simply ‘glyphs.’ To most of us, these glyphs look like pictures, but it is often hard to say what they are pictures of…. Unlike European languages, like English and Spanish, the ancient Maya writing did not use letters to spell words. Instead, they used a combination of glyphs that stood either for syllables, or for whole words. We will call the glyphs that stood for syllables ‘syllable glyphs,’ and we’ll call the glyphs that stood for whole words ‘logos.’ (The technically correct terms are ‘syllabogram’ and ‘logogram.’) It may seem complicated to use a combination of sounds and signs to make words, but we do the very same thing all the time. For example, you have seen this sign: ©iStock/©jswinborne Everyone knows that this sign means “one way to the right.” The “one way” part is spelled out in letters, as usual. But the “to the right” part is given only by the arrow pointing to the right. -

The Sweep of History

STUDENT’S World History & Geography 1 1 1 Essentials of World History to 1500 Ver. 3.1.10 – Rev. 2/1/2011 WHG1 The following pages describe significant people, places, events, and concepts in the story of humankind. This information forms the core of our study; it will be fleshed-out by classroom discussions, audio-visual mat erials, readings, writings, and other act ivit ies. This knowledge will help you understand how the world works and how humans behave. It will help you understand many of the books, news reports, films, articles, and events you will encounter throughout the rest of your life. The Student’s Friend World History & Geography 1 Essentials of world history to 1500 History What is history? History is the story of human experience. Why study history? History shows us how the world works and how humans behave. History helps us make judgments about current and future events. History affects our lives every day. History is a fascinating story of human treachery and achievement. Geography What is geography? Geography is the study of interaction between humans and the environment. Why study geography? Geography is a major factor affecting human development. Humans are a major factor affecting our natural environment. Geography affects our lives every day. Geography helps us better understand the peoples of the world. CONTENTS: Overview of history Page 1 Some basic concepts Page 2 Unit 1 - Origins of the Earth and Humans Page 3 Unit 2 - Civilization Arises in Mesopotamia & Egypt Page 5 Unit 3 - Civilization Spreads East to India & China Page 9 Unit 4 - Civilization Spreads West to Greece & Rome Page 13 Unit 5 - Early Middle Ages: 500 to 1000 AD Page 17 Unit 6 - Late Middle Ages: 1000 to 1500 AD Page 21 Copyright © 1998-2011 Michael G. -

ICONS and SIGNS from the ANCIENT HARAPPA Amelia Sparavigna ∗ Dipartimento Di Fisica, Politecnico Di Torino C.So Duca Degli Abruzzi 24, Torino, Italy

ICONS AND SIGNS FROM THE ANCIENT HARAPPA Amelia Sparavigna ∗ Dipartimento di Fisica, Politecnico di Torino C.so Duca degli Abruzzi 24, Torino, Italy Abstract Written words probably developed independently at least in three places: Egypt, Mesopotamia and Harappa. In these densely populated areas, signs, icons and symbols were eventually used to create a writing system. It is interesting to see how sometimes remote populations are using the same icons and symbols. Here, we discuss examples and some results obtained by researchers investigating the signs of Harappan civilization. 1. Introduction The debate about where and when the written words were originated is still open. Probably, writing systems developed independently in at least three places, Egypt, Mesopotamia and Harappa. In places where an agricultural civilization flourished, the passage from the use of symbols to a true writing system was early accomplished. It means that, at certain period in some densely populated area, signs and symbols were eventually used to create a writing system, the more complex society requiring an increase in recording and communication media. Signs, symbols and icons were always used by human beings, when they started carving wood or cutting stones and painting caves. We find signs on drums, textiles and pottery, and on the body itself, with tattooing. To figure what symbols used the human population when it was mainly composed by small groups of hunter-gatherers, we could analyse the signs of Native Americans. Our intuition is able to understand many of these old signs, because they immediately represent the shapes of objects and animals. It is then quite natural that signs and icons, born among people in a certain region, turn out to be used by other remote populations. -

Colonización, Resistencia Y Mestizaje En Las Américas (Siglos Xvi-Xx)

COLONIZACIÓN, RESISTENCIA Y MESTIZAJE EN LAS AMÉRICAS (SIGLOS XVI-XX) Guillaume Boccara (Editor) COLONIZACIÓN, RESISTENCIA Y MESTIZAJE EN LAS AMÉRICAS (SIGLOS XVI-XX) IFEA (Lima - Perú) Ediciones Abya-Yala (Quito - Ecuador) 2002 COLONIZACIÓN, RESISTENCIA Y MESTIZAJE EN LAS AMÉRICAS (SIGLOS XVI-XX) Guillaume Boccara (editor) 1ra. Edición: Ediciones Abya-Yala Av. 12 de octubre 14-30 y Wilson Telfs.: 593-2 2 506-267 / 593-2 2 562-633 Fax: 593-2 2 506-255 / 593-2 2 506-267 E-mail: [email protected] Casilla 17-12-719 Quito-Ecuador • Instituto Francés de Estudios Andinos IFEA Contralmirante Montero 141 Casilla 18-1217 Telfs: (551) 447 53 66 447 60 70 Fax: (511) 445 76 50 E-mail: [email protected] Lima 18-Perú ISBN: 9978-22-206-5 Diagramcación: Ediciones Abya-Yala Quito-Ecuador Diseño de portada: Raúl Yepez Impresión: Producciones digitales Abya-Yala Quito-Ecuador Impreso en Quito-Ecuador, febrero del 2002 Este libro corresponde al tomo 148 de la serie “Travaux de l’Institut Francais d’Etudes Andines (ISBN: 0768-424-X) INDICE Introducción Guillaume Boccara....................................................................................................................... 7 Primera parte COLONIZACIÓN, RESISTENCIA Y MESTIZAJE (EJEMPLOS AMERICANOS) I. Jonathan Hill & Susan Staats: Redelineando el curso de la historia: Estados euro-americanos y las culturas sin pueblos..................................................................................................................... 13 II. José Luis Martínez, Viviana Gallardo, & Nelson -

The Calendars of India

The Calendars of India By Vinod K. Mishra, Ph.D. 1 Preface. 4 1. Introduction 5 2. Basic Astronomy behind the Calendars 8 2.1 Different Kinds of Days 8 2.2 Different Kinds of Months 9 2.2.1 Synodic Month 9 2.2.2 Sidereal Month 11 2.2.3 Anomalistic Month 12 2.2.4 Draconic Month 13 2.2.5 Tropical Month 15 2.2.6 Other Lunar Periodicities 15 2.3 Different Kinds of Years 16 2.3.1 Lunar Year 17 2.3.2 Tropical Year 18 2.3.3 Siderial Year 19 2.3.4 Anomalistic Year 19 2.4 Precession of Equinoxes 19 2.5 Nutation 21 2.6 Planetary Motions 22 3. Types of Calendars 22 3.1 Lunar Calendar: Structure 23 3.2 Lunar Calendar: Example 24 3.3 Solar Calendar: Structure 26 3.4 Solar Calendar: Examples 27 3.4.1 Julian Calendar 27 3.4.2 Gregorian Calendar 28 3.4.3 Pre-Islamic Egyptian Calendar 30 3.4.4 Iranian Calendar 31 3.5 Lunisolar calendars: Structure 32 3.5.1 Method of Cycles 32 3.5.2 Improvements over Metonic Cycle 34 3.5.3 A Mathematical Model for Intercalation 34 3.5.3 Intercalation in India 35 3.6 Lunisolar Calendars: Examples 36 3.6.1 Chinese Lunisolar Year 36 3.6.2 Pre-Christian Greek Lunisolar Year 37 3.6.3 Jewish Lunisolar Year 38 3.7 Non-Astronomical Calendars 38 4. Indian Calendars 42 4.1 Traditional (Siderial Solar) 42 4.2 National Reformed (Tropical Solar) 49 4.3 The Nānakshāhī Calendar (Tropical Solar) 51 4.5 Traditional Lunisolar Year 52 4.5 Traditional Lunisolar Year (vaisnava) 58 5. -

Student's Friend World History & Geography 1

STUDENT’S World History & Geography 1 Essentials of World History to 1500 Ver. 3.1.12 - Rev. 7/1/16 WHG1 The following pages describe significant people, places, events, and concepts in the story of humankind. This information forms the core of our study; it will be fleshed-out by classroom discussions, audio-visual materials, readings, writings, and other activities. This knowledge will help you understand how the world works and how humans behave. It will help you understand many of the books, news reports, films, articles, and events you will encounter throughout the rest of your life. from: www.studentsfriend.com The Student’s Friend World History & Geography 1 Essentials of world history to 1500 History What is history? History is the story of human experience. Why study history? • History shows us how the world works and how humans behave. • History helps us make judgments about current and future events. • History affects our lives every day. • History is a fascinating story of human treachery and achievement. Geography What is geography? Geography is the study of interaction between humans and the environment. Why study geography? • Geography is a major factor affecting human development. • Humans are a major factor affecting our natural environment. • Geography affects our lives every day. • Geography helps us better understand the peoples and places of the world. CONTENTS: Overview of history Page 1 Some basic concepts Page 2 Unit 1 - Origins of the Earth and Humans Page 3 Unit 2 - Civilization Arises in Mesopotamia & Egypt Page 5 Unit 3 - Civilization Spreads East to India & China Page 9 Unit 4 - Civilization Spreads West to Greece & Rome Page 13 Unit 5 - Early Middle Ages: 500 to 1000 AD Page 17 Unit 6 - Late Middle Ages: 1000 to 1500 AD Page 21 Copyright © 2016 www.studentsfriend.com The Student’s Friend: World History & Geography 1 may be freely reproduced and distributed by teachers and students for educational purposes. -

Isthmian Script: Internal Variation in Two Dated Texts

Glyph Dwellers Report 55 July 2017 Isthmian Script: Internal Variation in Two Dated Texts Martha J. Macri Professor Emerita, Department of Native American Studies University of California, Davis The origins of the ancient Mesoamerican scripts and their interrelationships remain topics of conjecture. Our knowledge of the relative time spans of these scripts and their geographic ranges is based on our knowledge of only a fraction of the texts that once existed. In spite of this limitation, it is possible, in at least one case, to find information within the texts themselves that provides some insight into the date of origin. This note looks at differences between the Isthmian texts of La Mojarra Stela 1 and the Tuxtla Statuette, two objects with clear long count dates, in order to suggest that the origin of the script must be significantly earlier than either of these texts (for images of these texts see George Stuart's drawings in Winfield Capitaine 1988). It is generally accepted that the dates on La Mojarra Stela 1 and the Tuxtla Statuette fell close to the time of their carving. The two texts contain long count dates that are only six years apart. The long count 8.5.16.9.7 (156 CE), is the later of two long count dates on La Mojarra Stela 1, and 8.6.2.4.17 (162 CE) is on the front of the Tuxtla Statuette. Differences between them provide evidence of the existence of two script varieties, showing that the script's origin predates these two examples by decades, if not centuries. -

An Isthmian Presence on the Pacific Piedmont of Guatemala

Glyph Dwellers Report 65 October 2020 An Isthmian Presence on the Pacific Piedmont of Guatemala Martha J. Macri Professor Emerita, Department of Native American Studies University of California, Davis A dichotomy between Olmec and Maya art styles on the stone monuments of the Guatemalan site of Tak'alik Ab'aj was proposed a number of years ago (e.g., Graham 1979). Researchers now recognize a more nuanced division between Olmec and developing Isthmian/Maya1 traditions (Graham 1989; Mora- Marín 2005; Popenoe de Hatch, Schieber de Lavarreda, and Orrego Corzo 2011; Schieber de Lavarreda 2020; Schieber de Lavarreda and Orrego Corzo 2010). John Graham proposed the term "Early Isthmian" rather than "Olmec" to describe examples of the Preclassic texts of southern Mesoamerica (Graham 1971:134). In this paper the term "Isthmian" is restricted to the script found on the Tuxtla Statuette (Holmes 1907), La Mojarra Stela 1 (Winfield Capitaine 1988), and related texts. Internal evidence within Isthmian texts themselves, specifically variation in both sign use and sign form, suggests that the origin of the Isthmian script dates significantly earlier than the long count dates on the two earliest known examples: La Mojarra Stela 1 and the Tuxtla Statuette (Macri 2017a). Two items of stratigraphic evidence from Chiapa de Corzo, Chiapas show a presence of the script at that site, beyond the Gulf region, pushing the origin of the script even further back in time (Macri 2017b). This report considers several texts from the Guatemalan site of Tak'alik Ab'aj, specifically two monuments, that have long count dates only slightly earlier those on La Mojarra Stela 1 and the Tuxtla Statuette, to suggest an even broader geographic and temporal range for the Isthmian script tradition. -

©2018 Travis Jeffres ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

©2018 Travis Jeffres ALL RIGHTS RESERVED “WE MEXICAS WENT EVERYWHERE IN THAT LAND”: THE MEXICAN INDIAN DIASPORA IN THE GREATER SOUTHWEST, 1540-1680 By TRAVIS JEFFRES A dissertation submitted to the School of Graduate Studies Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History Written under the direction of Camilla ToWnsend And approVed by _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ _____________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey October, 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “We Mexicas Went Everywhere in That Land:” The Mexican Indian Diaspora in the Greater Southwest, 1540-1680 by TRAVIS JEFFRES Dissertation Director: Camilla ToWnsend Beginning With Hernando Cortés’s capture of Aztec Tenochtitlan in 1521, legions of “Indian conquistadors” from Mexico joined Spanish military campaigns throughout Mesoamerica in the sixteenth century. Scholarship appearing in the last decade has revealed the aWesome scope of this participation—involving hundreds of thousands of Indian allies—and cast critical light on their motiVations and experiences. NeVertheless this Work has remained restricted to central Mexico and areas south, while the region known as the Greater SouthWest, encompassing northern Mexico and the U.S. Southwest, has been largely ignored. This dissertation traces the moVements of Indians from central Mexico, especially Nahuas, into this region during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and charts their experiences as diasporic peoples under colonialism using sources they Wrote in their oWn language (Nahuatl). Their activities as laborers, soldiers, settlers, and agents of acculturation largely enabled colonial expansion in the region. However their exploits are too frequently cast as contributions to an overarching Spanish colonial project. -

Chichimecas of War.Pdf

Chichimecas of War Edit Regresión Magazine Winter 2017 EDITORIAL This compilation is a study concerning the fiercest and most savage natives of Northern Mesoamerica. The ancient hunter-gatherer nomads, called “Chichimecas,” resisted and defended with great daring their simple ways of life, their beliefs, and their environment,. They decided to kill or die for that which they considered part of themselves, in a war declared against all that was alien to them. We remember them in this modern epoch not only in order to have a historical reference of their conflict, but also as evidence of how, due to the simple fact of our criticism of technology, sharpening our claws to attack this system and willing to return to our roots, we are reliving this war. Just like our ancestors, we are reviving this internal fire that compels us to defend ourselves and defend all that is Wild. Many conclusions can be taken from this study. The most important of these is to continue the war against the artificiality of this civilization, a war against the technological system that rejects its values and vices. Above all, it is a war for the extremist defense of wild nature. Axkan kema tehuatl nehuatl! Between Chichimecas and Teochichimecas According to the official history, in 1519, the Spanish arrived in what is now known as “Mexico”. It only took three years for the great Aztec (or Mexica) empire and its emblematic city, Tenochtitlán, to fall under the European yoke. During the consolidation of peoples and cities in Mexica territory, the conquistadors’ influence increasingly extended from the center of the country to Michoacán and Jalisco. -

The Visions of a Guachichil Witch in 1599: a Window on the Subjugation of Mexico's Hunter-Gatherers Author(S): Ruth Behar Source: Ethnohistory, Vol

The Visions of a Guachichil Witch in 1599: A Window on the Subjugation of Mexico's Hunter-Gatherers Author(s): Ruth Behar Source: Ethnohistory, Vol. 34, No. 2 (Spring, 1987), pp. 115-138 Published by: Duke University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/482250 Accessed: 24-07-2016 16:17 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Duke University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Ethnohistory This content downloaded from 141.211.4.224 on Sun, 24 Jul 2016 16:17:54 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms The Visions of a Guachichil Witch in 1599: A Window on the Subjugation of Mexico's Hunter-Gatherers Ruth Behar, University of Michigan Abstract. On a single day in 1599 an old Guachichil woman was tried and hanged for witchcraft in San Luis Potosi, the newly pacified northern frontier of New Spain. Using the Spanish encounter with the hunter-gatherer Guachichiles as background, this paper provides a cultural analysis of the old woman's visions and prophecies of a new world in which there would be no Spaniards and the Indians would have eternal life.