World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wetlands of the Nile Basin the Many Eco for Their Liveli This Chapt Distribution, Functions and Contribution to Contribution Livelihoods They Provide

important role particular imp into wetlands budget (Sutch 11 in the Blue N icantly 1110difi Wetlands of the Nile Basin the many eco for their liveli This chapt Distribution, functions and contribution to contribution livelihoods they provide. activities, ane rainfall (i.e. 1 Lisa-Maria Rebelo and Matthew P McCartney climate chan: food securit; currently eX' arc under tb Key messages water resour support • Wetlands occur extensively across the Nile Basin and support the livelihoods ofmillions of related ;;ervi people. Despite their importance, there are big gaps in the knowledge about the current better evalu: status of these ecosystems, and how populations in the Nile use them. A better understand systematic I ing is needed on the ecosystem services provided by the difl:erent types of wetlands in the provide. Nile, and how these contribute to local livelihoods. • While many ofthe Nile's wetlands arc inextricably linked to agricultural production systems the basis for making decisions on the extent to which, and how, wetlands can be sustainably used for agriculture is weak. The Nile I: • Due to these infi)fl11atio!1 gaps, the future contribution of wetlands to agriculture is poorly the basin ( understood, and wetlands are otten overlooked in the Nile Basin discourse on water and both the E agriculture. While there is great potential for the further development of agriculture and marsh, fen, fisheries, in particular in the wetlands of Sudan and Ethiopia, at the same time many that is stat wetlands in the basin are threatened by poor management practices and populations. which at \, In order to ensure that the future use of wetlands for agriculture will result in net benefits (i.e. -

From Water to Resource: a Case of Stakeholders' Involvement In

V Department of Water and Environmental Studies Tema Institute Linköping University From Water to Resource: A Case of Stakeholders’ Involvement in Usangu Catchment Jofta M. Timanywa Master’s programme in Science for Sustainable Development Master’s Thesis, 30 ECTS ISRN: LIU-TEMAV/MPSSD-A--09/001--SE Linköpings Universitet V Department of Water and Environmental Studies Tema Institute Linköping University From Water to Resource: A Case of Stakeholders’ Involvement in Usangu Catchment Jofta M. Timanywa Master’s programme in Science for Sustainable Development Master’s Thesis, 30 ECTS Supervisor: Prof. Anders Hjort af Ornäs Examiner: Hans Holmen Upphovsrätt Detta dokument hålls tillgängligt på Internet – eller dess framtida ersättare – under 25 år från publiceringsdatum under förutsättning att inga extraordinära omständigheter uppstår. Tillgång till dokumentet innebär tillstånd för var och en att läsa, ladda ner, skriva ut enstaka kopior för enskilt bruk och att använda det oförändrat för ickekommersiell forskning och för undervisning. Överföring av upphovsrätten vid en senare tidpunkt kan inte upphäva detta tillstånd. All annan användning av dokumentet kräver upphovsmannens medgivande. För att garantera äktheten, säkerheten och tillgängligheten finns lösningar av teknisk och administrativ art. Upphovsmannens ideella rätt innefattar rätt att bli nämnd som upphovsman i den omfattning som god sed kräver vid användning av dokumentet på ovan beskrivna sätt samt skydd mot att dokumentet ändras eller presenteras i sådan form eller i sådant sammanhang som är kränkande för upphovsmannens litterära eller konstnärliga anseende eller egenart. För ytterligare information om Linköping University Electronic Press se förlagets hemsida http://www.ep.liu.se/. Copyright The publishers will keep this document online on the Internet – or its possible replacement – for a period of 25 years starting from the date of publication barring exceptional circumstances. -

Anatomy of the Nile Following the Twists and Turns of the World's Longest River

VideoMedia Spotlight Anatomy of the Nile Following the twists and turns of the world's longest river For the complete video with media resources, visit: http://education.nationalgeographic.org/media/anatomy-nile/ Funder The Nile River has provided fertile land, transportation, food, and freshwater to Egypt for more than 5,000 years. Today, 95% of Egypt’s population continues to live along its banks. Where does the Nile begin? Where does it end? Watch this video, from Nat Geo WILD’s “Destination Wild” series, to find out. For an even deeper look at the Nile, use our vocabulary list and explore our “geo-tour” of the Nile to understand the geography of the river and answer the questions in the Questions tab. Questions Where is the source, or headwaters, of the Nile River? The streams of Rwanda’s Nyungwe Forest are probably the most remote sources of the Nile. The snow-capped peaks of the Rwenzori Mountains are another one of the remote sources of the Nile. The Rwenzori Mountains, sometimes nicknamed the “Mountains of the Moon,” straddle the border between the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Uganda. Many geographers also consider Lake Victoria, the largest lake in Africa, to be a source of the Nile. The most significant outflow from Lake Victoria, winding northward through Uganda, is called the “Victoria Nile.” Can you find a waterfall on the Nile River? As it twists more than 6,500 kilometers (4,200 miles) through Africa, the Nile has dozens of small and large waterfalls. The most significant waterfall on the Nile is probably Murchison Falls, Uganda. -

Assessing the Bujagali Hydropower Project in Uganda

Modern Approaches in Oceanography and Petrochemical Sciences DOI: 10.32474/MAOPS.2019.02.000141 ISSN: 2637-6652 Research Article Assessing the Bujagali Hydropower Project in Uganda George Kimbowa1 and Khaldoon A Mourad2* 1Busitema University, Uganda 2Center for Middle Eastern Studies, Lund, Sweden *Corresponding author: Khaldoon A Mourad, Center for Middle Eastern Studies, Lund, Sweden Received: January 21, 2019 Published: January 29, 2019 Abstract The development of great dams and hydropower plants increases power supply and access. However, the process is considered a threat to livelihoods, ecosystem and biodiversity because in most cases it brings about human displacement and natural resources degradation. This paper seeks to assess the development of the Bujagali Hydropower Plant in Uganda (BHP) and its compliance with IWRM principles based on water knowledges, societal values, and inter-disciplinary approach. The paper develops a set of strategic interventions for the dam and the BHP based on SWOT analysis, XLRM framework, Multi-sectoral and interdisciplinary development approach, and sustainable management. These measures are deemed socially and ecologically acceptable by all stakeholders including the cultural and historical institutions, societal actor groups, including mega-hydraulic bureaucracies, the private sectors and national politicians. The results show that project developers should always carry out Environment and Social Impact Assessments (ESIA); develop timely ‘Resettlement Action Plan’; carry out informed consultation and participation; promote transparency; and communicate project’s risks, potential impacts and probable mitigation actions to attain sustainability. The paper proposes some policy interventions to be implemented along the project’s lifetime. Furthermore, it presents a sustainable development plan for such projects based on the IWRM principles. -

Bujagali Final Report

INDEPENDENT REVIEW PANEL COMPLIANCE REVIEW REPORT ON THE BUJAGALI HYDROPOWER AND INTERCONNECTION PROJECTS June 20, 2008 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The IRM Compliance Review Panel could not have undertaken and completed this report without the generous assistance of many people in Uganda and at the African Development Bank. It wishes to express its appreciation to all of them for their cooperation and support during the compliance review of the Bujagali Hydropower and Interconnection projects. The Panel thanks the Requesters and the many individuals from civil society and the communities that it met in the Project areas and in Kampala for their assistance. It also appreciates the willingness of the representatives of the Government of Uganda and the projects’ sponsors to meet with the Panel and provide it with information during its visit to Uganda. The Panel acknowledges all the help provided by the Resident Representative of the African Development Bank in Uganda and his staff and the willing cooperation it has received from the Bank’s Management and staff in Tunis. The Panel appreciates the generous cooperation of the World Bank Inspection Panel which conducted its own review of the “UGANDA: Private Power Generation Project”. The Compliance Review Panel and the World Bank Inspection Panel coordinated their field investigations of the Bujagali projects and shared consultants and technical information during this investigation in order to enhance the efficiency and cost effectiveness of each of their investigations. While this collaboration between the Panel and the World Bank Inspection Panel worked to the mutual benefit of both parties, each Panel focused its compliance review on its own Bank’s policies and procedures and each Panel has made its own independent judgments about the compliance of its Management and staff with its Bank’s policies and procedures. -

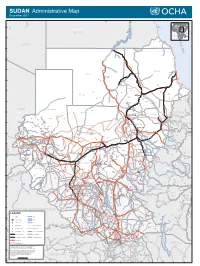

SUDAN Administrative Map December 2011

SUDAN Administrative Map December 2011 Faris IQLIT Ezbet Dush Ezbet Maks el-Qibli Ibrim DARAW KOM OMBO Al Hawwari Al-Kufrah Nagel-Gulab ASWAN At Tallab 24°N EGYPT 23°N R E LIBYA Halaib D S 22°N SUDAN ADMINISTRATED BY EGYPT Wadi Halfa E A b 'i Di d a i d a W 21°N 20°N Kho r A bu Sun t ut a RED SEA a b r A r o Porth Sudan NORTH Abu Hamad K Dongola Suakin ur Qirwid m i A ad 19°N W Bauda Karima Rauai Taris Tok ar e il Ehna N r e iv R RIVER NILE Ri ver Nile Desert De Bayouda Barbar Odwan 18°N Ed Debba K El Baraq Mib h o r Adara Wa B a r d a i Hashmet Atbara ka E Karora l Atateb Zalat Al Ma' M Idd Rakhami u Abu Tabari g a Balak d a Mahmimet m Ed Damer Barqa Gereis Mebaa Qawz Dar Al Humr Togar El Hosh Al Mahmia Alghiena Qalat Garatit Hishkib Afchewa Seilit Hasta Maya Diferaya Agra 17°N Anker alik M El Ishab El Hosh di El Madkurab Wa Mariet Umm Hishan Qalat Kwolala Shendi Nakfa a r a b t Maket A r a W w a o d H i i A d w a a Abdullah Islandti W b Kirteit m Afabet a NORTH DARFUR d CHAD a Zalat Wad Tandub ug M l E i W 16°N d Halhal Jimal Wad Bilal a a d W i A l H Aroma ERITREA Keren KHARTOUM a w a KASSALA d KHARTOUM Hagaz G Sebderat Bahia a Akordat s h Shegeg Karo Kassala Furawiya Wakhaim Surgi Bamina New Halfa Muzbat El Masid a m a g Barentu Kornoi u Malha Haikota F di Teseney Tina Um Baru El Mieiliq 15°N Wa Khashm El Girba Abu Quta Abu Ushar Tandubayah Miski Meheiriba EL GEZIRA Sigiba Rufa'ah Anka El Hasahisa Girgira NORTH KORDOFAN Ana Bagi Baashim/tina Dankud Lukka Kaidaba Falankei Abdel Shakur Um Sidir Wad Medani Sodiri Shuwak Badime Kulbus -

The Politics of the Nile Basin

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Wits Institutional Repository on DSPACE THE POLITICS OF THE NILE BASIN ELIAS ASHEBIR Supervisor:- Larry Benjamin A Dissertation Submitted to the Department of International Relations, at the University of the WitWatersRand, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Obtaining the Degree of Master of Arts in Hydropotitics Studies Johannesburg 2009 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this dissertation is my own unaided and has not been submitted to any other University for any other degree. Elias Ashebir May 2009 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgment.............................. VI Abstract ................................... VII Introduction................................ VIII Chapter I A Brief Survey of the Nile Basin 1. General overview 1-3 2. Exploration of the Nile 3. Geographical & Hydrological Feature of the Nile Basin 3-4 3.1 The Blue Nile 4 3.2 The White Nile 4-9 Chapter II The Nile Riparian Countries & Future Challenges 1. Subsystems of the Nile Basin 10 1.1 The White Nile Subsystem 11 1.2 The Abbay (Blue Nile) Subsystem 11-12 1.3 The Tekeze (Atbara) Subsystem 12 1.4 The Baro-Akobo (Sobat) Subsystem 12-13 2. General Descriptions of the Nile Riparian Countries 2.1 Upper Riparian Countries of the Nile Basin a) Ethiopia 14-24 b) Eritrea 24-26 c) Kenya 27-32 2.2 The Equatorial upper riparian countries a) Tanzania 32-37 b) Uganda 37-41 c) Democratic Republic of Congo 42-46 3 d) Rwanda 47-50 e) Burundi 50-53 2.3 The Lower riparian countries a) Egypt 53-57 b) Sudan 57-62 Chapter III Legal aspects of the use of the Nile waters 1. -

Water Sharing in the Nile River Valley

PROJECT GNV011 : USING GIS/REMOTE SENSING FOR THE SUSTAINABLE USE OF NATURAL RESOURCES Water Sharing in the Nile River Valley Diana Rizzolio Karyabwite UNEP/DEWA/GRID -Geneva January -March 1999 January-June 2000 Water Sharing in the Nile River Valley ABSTRACT The issue of freshwater is one of highest priority for the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). The Nile Basin by its size, political divisions and history constitutes a major freshwater-related environmental resource and focus of attention. UNEP/DEWA/GRID-Geneva initiated several case studies stressing a river basin approach to the integrated and sustainable management of freshwater resources. In 1998 GRID-Geneva started a project on Water Sharing in the Nile River Basin. The Nile Valley project was set up to prepare an experimental methodology to identify the potential water-related issues in a watershed. The first stage of the project consisted of the compilation of available geoferenced data sets for the Nile valley region to be used as inputs for water bala nce modelling; and led to the elaboration of a first report1. Available georeferenced data sets have been stored in Arc/Info-ArcView. They serve as inputs for water balance modelling. General data on transboundary water sharing and on the Nile River Basin were also collected. Several international projects operating in the Nile River Valley are oriented towards Nile Basin water management, using GIS and remote sensing techniques. Therefore any continuation of the GRID- Geneva Nile River project should be linked with and integrated into one of these successful field programmes. 1 Booth J., Jaquet J.-M., December 1998. -

Food Security in the White Nile State of Sudan Food Security in The

FOOD SECURITY IN THE WHITE NILE STATE OF SUDAN FOOD SECURITY IN THE WHITE NILE STATE OF SUDAN ANALYSIS OF 2010 STATE LEVEL BASELINE HOUSEHOLD SURVEY (Analysis of 2010 State level Baseline Household Survey) This study is one of the papers selected for funding by SIFSIA for the support of food security research and capacity building initiatives identified at the (Analysis of 2010 State level Baseline Householdlocal/state Survey)level. The main purpose of the research is to improve understanding of food security issues in Sudan and inform decision makers about the evolving food security situation in the selected States. The main expected outcome of such studies should be an Conducted enhanced decentralized capacity in food security analysis and in food security policy and planning. FOOD SECURITY TECHNICAL SECRETARIAT / MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE (FSTS) FAO- SUDAN INTEGRATED FOOD SECURITY INFORMATION FOR ACTION (SIFSIA) KHARTOUM, SUDAN JUNE - 2011 SIFSIA project :: is funded by European Union Stabex Funds and jointly implementedi by the Government of Sudan and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN (FAO). The project aims at strengthening the government capacity in collecting, analysing disseminating, and utilizing food security information. For more information visit www.fao.org/sudanfoodsecurity/en FOOD SECURITY IN THE WHITE NILE STATE OF SUDAN CONTENTS CONTENTS .................................................................................................................................................................... i LIST -

United Republic of Tanzania

Country profile – United Republic of Tanzania Version 2016 Recommended citation: FAO. 2016. AQUASTAT Country Profile – United Republic of Tanzania. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Rome, Italy The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO as the source and copyright holder is given and that FAO’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way. All requests for translation and adaptation rights, and for resale and other commercial use rights should be made via www.fao.org/contact-us/licencerequest or addressed to [email protected]. FAO information products are available on the FAO website (www.fao.org/ publications) and can be purchased through [email protected]. -

The Environmental Resources of the Nile Basin

Chapter 3 The Environmental Resources of the Nile Basin 12.3% cities/ 1.0% 1.4% forests built-up areas grasslands water bodies shrublands bare soils agricultural –1.3% & woodlands land –4.7% –10.1% –17.9% 57 KEY MESSAGES • The Nile Basin has many unique aquatic and to conserve the basin’s unique ecosystems, with terrestrial ecosystems, and is home to thousands mixed conservation success. of species of plants and animals, many of them • The root causes of the rapid degradation of the endemic to the basin. basin’s environmental resources are population • The basin’s water and related environmental growth, poverty, civil insecurity, and weak policy, resources provide a wide range of societal goods legal, and institutional frameworks in the Nile and services, contributing between 40 and 60 per riparian countries. cent of the gross domestic product of the Nile • The Lake Victoria Basin Commission (LVBC), the riparian countries. Intergovernmental Authority on Development • The Nile’s system of waterways and wetlands (IGAD), and the Nile Basin Initiative (NBI) are constitutes an important flight path for migratory examples of a growing number of regional birds and also a destination for migratory birds frameworks established in recent years to address from other regions of Africa. Seventeen aquatic environmental degradation within the Nile Basin. and wetland ecosystems within the basin have been designated as international Ramsar sites. • Key recommendations for regional-level actions by the Nile riparian countries include the • Natural resources of the Nile Basin are under restoration of degraded water catchments critical increasing pressure from a multiplicity of sources, for sustaining the flow of the major Nile tributaries, mainly agriculture, livestock, invasive species, restoring badly degraded lands that export large bushfires, mining, urbanization, climate change, quantities of sediments and cause serious siltation and natural disasters. -

NOTES on the SUDANESE TRIBES of the WHITE NILE. the Sudan

J R Army Med Corps: first published as 10.1136/jramc-03-05-03 on 1 November 1904. Downloaded from 489 NOTES ON THE SUDANESE TRIBES OF THE WHITE NILE. By CAPTAIN S. L. CUMMINS. Royal A1'fny .:.l1edical Corp8 (Egyptian Army). THE Sudan, a word derived from the Arabic root, "Sood," to blacken, was the name given by slave-dealing Arabs to their happy hunting ground along the White Nile and into Equatorial Africa; the land of the black people. Under a geographical nomenclature, a number of Arab tribes might now be called Sudanese, since they are inhabitants of the Sudan. In this article only those tribes are so called that, dwelling in the Sudan, are free from all trace of recent Arab blood. The material to be dealt with, even thus limited, is immense, and only the very general ignorance that exists on the subject gives me courage to Protected by copyright. attempt it. It is, indeed, surprising that. seeing how deeply con cerned we are in the development of the country, many English people know so little about it, and that the number of educated men capable of naming a· single Sudanese tribe is insignificant. The number of pure Sudanese tribes left, after the Arabs have been eliminated, is very great. They differ from each other in appear ance, in language, in occupation, and largely also in customs, though many customs are common to widely differing tribes, as one would expect, seeing that similar conditions and necessities tend to be met similarly by primitive peoples. Even within the unit of the tribe itself there are sub-divisions, distinguished not so much by a divergence in customs as by the http://militaryhealth.bmj.com/ artificial barriers of old feuds and quarrels; by envy, hatred, alid malice, and all uncharitableness.