Charles Armstrong 24 October 2012 Linguistics Research Thesis Advisor: Prof

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Midnight Special Songlist

west coast music Midnight Special Please find attached the Midnight Special song list for your review. SPECIAL DANCES for Weddings: Please note that we will need your special dance requests, (I.E. First Dance, Father/Daughter Dance, Mother/Son Dance etc) FOUR WEEKS in advance prior to your event so that we can confirm that the band will be able to perform the song(s) and that we are able to locate sheet music. In some cases where sheet music is not available or an arrangement for the full band is need- ed, this gives us the time needed to properly prepare the music and learn the material. Clients are not obligated to send in a list of general song requests. Many of our clients ask that the band just react to whatever their guests are responding to on the dance floor. Our clients that do provide us with song requests do so in varying degrees. Most clients give us a handful of songs they want played and avoided. Recently, we’ve noticed in increase in cli- ents customizing what the band plays and doesn’t play with very specific detail. If you de- sire the highest degree of control (allowing the band to only play within the margin of songs requested), we ask for a minimum of 100 requests. We want you to keep in mind that the band is quite good at reading the room and choosing songs that best connect with your guests. The more specific/selective you are, know that there is greater chance of losing certain song medleys, mashups, or newly released material the band has. -

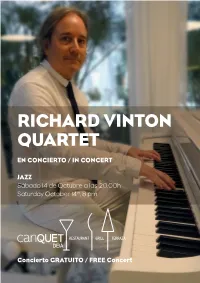

Richard Vinton Quartet

CONCIERTO GRATUITO CAN QUET ABRE A LAS 19:00 H Y EL CONCIERTO COMIENZA A LAS 20:00 H. LA COCINA ESTÁ ABIERTA DESDE LAS 19.00 H. FREE CONCERT CAN QUET OPENS AT 7 P.M. AND THE CONCERT STARTS AT 8 P.M. THE KITCHEN OPENS ON 7 P.M. RICHARD VINTON QUARTET EN CONCIERTO / IN CONCERT Ctra. Valldemossa-Deià, s/n. JAZZ 07179 - Deià - Illes Balears Sábado 14 de Octubre a las 20.00h Tel: (+34) 971 639 196 Saturday October 14th, 8 pm [email protected] www.restaurantecanquet.com @canquetdeya Abierto: Miércoles a Domingo 19:00 a 24:00 h Parking para Clientes Concierto GRATUITO / FREE Concert RICHARD VINTON piano RICHARD VINTON piano El conocido pianista, arreglista y educador nació en Florida, The well-known pianist, arranger and educator was born in Florida, USA. Apart EEUU. Aparte de sus Bachelors de Música del New England from his Music Bachelors of the New England Conservatory in Boston and his Conservatory en Boston y su Masters de Música de la University Masters of Music from the University of Miami he studied jazz piano and com- of Miami estudió jazz piano y composición en la Berklee College position at the Berklee College of Music and worked among others with the of Music y trabajó entre otros con the Mavericks y Tony Bennett. Mavericks and Tony Bennett. En Mallorca Richard ha colaborado con The Drifters (Son Amar), Richard, who lives in Mallorca since twenty years, has collaborated with The Drifters Come Fly With Me (Gran Casino Mallorca), Michelle McCain, (Son Amar), Come Fly With Me (Gran Casino Mallorca), Michelle McCain, Jaime An- Jaime Anglada, Conxa Buika, Cap Pella y la Orquestra Simfònica glada, Conxa Buika, Cap Pella and the Symphony Orchestra of the Balearic Islands. -

Host's Master Artist List

Host's Master Artist List You can play the list in the order shown here, or any order you prefer. Tick the boxes as you play the songs. Backstreet Boys Paul Simon Pearl Jam Tina Turner Jamiroquai Bryan Adams Chaka Demus & Pliers Vengaboys Robbie Williams Kool & The Gang Lenny Kravitz Haircut 100 Sinitta Simple Minds M People Dead Or Alive Manic Street Preachers Tiffany Meat Loaf Billy Ocean Communards Musical Youth Tight Fit Cyndi Lauper Space Eurythmics Kiss Five Star Dollar Shania Twain Cher Style Council Stone Roses Lighthouse Family Simply Red Billy Ray Cyrus Blur Aerosmith Cure Mark Morrison U2 Inspiral Carpets Madonna Shakin Stevens Rick Ashley Racey Salt N Pepper Michael Jackson Luther Vandross Christina Aguilera Copyright QOD Page 1/26 Team/Player Sheet 1 Good Luck! Chaka Demus & Dollar Vengaboys Meat Loaf Simple Minds Pliers Manic Street Billy Ray Cyrus Pearl Jam Mark Morrison M People Preachers Musical Youth Rick Ashley Lenny Kravitz Inspiral Carpets Five Star U2 Simply Red Communards Eurythmics Dead Or Alive Copyright QOD Page 2/26 Team/Player Sheet 2 Good Luck! Cher Blur Salt N Pepper Simple Minds Tina Turner Manic Street Mark Morrison Aerosmith Billy Ray Cyrus Michael Jackson Preachers Tight Fit Pearl Jam Musical Youth Christina Aguilera Jamiroquai Chaka Demus & M People Luther Vandross Communards Cure Pliers Copyright QOD Page 3/26 Team/Player Sheet 3 Good Luck! U2 Jamiroquai Dollar M People Michael Jackson Billy Ray Cyrus Racey Five Star Billy Ocean Simply Red Chaka Demus & Luther Vandross Communards Eurythmics Christina -

El Ritmo De Las Palabras: Concha Buika

MUSIC El ritmo de las palabras: NEW YORK Concha Buika Wed, June 17, 2015 7:00 pm Venue Instituto Cervantes, 211 East 49th Street, New York, NY 10017 View map Phone: 212-308-7720 Admission Free admission, limited seating. RSVP required at [email protected] by Tuesday, June 16. More information Instituto Cervantes New York The Spanish Grammy winning artist Concha Buika will Credits ‘perform’ poems, stories and chants from her recent book, A Organized by the Consulate general of Spain in New York, Instituto los que amaron a mujeres difíciles y acabaron por soltarse. Cervantes New York and Books & Books. Born in Palma de Mallorca, Spain, as the daughter of African parents and hailed as a star in contemporary world music, jazz, flamenco, and fusion, Buika posesses a unique blend of influences as well as a remarkable voice –raw and smoky, but with a tenderness that hits right at the heart, vibrantly deploying her rich, sensual and husky instrument. In 2011, NPR listed her spellbinding sound among its 50 Great Voices, calling hers the voice of freedom. She has received multiple awards and nominations, such as Latin Grammys for Best Album and Best Production for Niña de Fuego and Best Traditional Tropical Album for El Último Trago, and she was nominated again in 2014 for Record of the Year for La Noche Más Larga and for Best Latin Jazz Album at the 2014 Grammy Awards. Book purchase necessary to attend. Book signing after the event. Embassy of Spain – Cultural Office | 2801 16th Street, NW, Washington, D.C. 20009 | Tel: (202) 728-2334 View this event online: https://www.spainculture.us/city/new-york/el-ritmo-de-las-palabras-concha-buika/ Created on 09/27/2021 | Page 1 of 1. -

Estrella Morente Lead Guitarist: José Carbonell "Montoyita"

Dossier de prensa ESTRELLA MORENTE Vocalist: Estrella Morente Lead Guitarist: José Carbonell "Montoyita" Second Guitarist: José Carbonell "Monty" Palmas and Back Up Vocals: Antonio Carbonell, Ángel Gabarre, Enrique Morente Carbonell "Kiki" Percussion: Pedro Gabarre "Popo" Song MADRID TEATROS DEL CANAL – SALA ROJA THURSDAY, JUNE 9TH AT 20:30 MORENTE EN CONCIERTO After her recent appearance at the Palau de la Música in Barcelona following the death of Enrique Morente, Estrella is reappearing in Madrid with a concert that is even more laden with sensitivity if that is possible. She knows she is the worthy heir to her father’s art so now it is no longer Estrella Morente in concert but Morente in Concert. Her voice, difficult to classify, has the gift of deifying any musical register she proposes. Although strongly influenced by her father’s art, Estrella likes to include her own things: fados, coplas, sevillanas, blues, jazz… ESTRELLA can’t be described described with words. Looking at her, listening to her and feeling her is the only way to experience her art in an intimate way. Her voice vibrates between the ethereal and the earthly like a presence that mutates between reality and the beyond. All those who have the chance to spend a while in her company will never forget it for they know they have been part of an inexplicable phenomenon. Tonight she offers us the best of her art. From the subtle simplicity of the festive songs of her childhood to the depths of a yearned-for love. The full panorama of feelings, the entire range of sensations and colours – all the experiences of the woman of today, as well as the woman of long ago, are found in Estrella’s voice. -

Bad Habit Song List

BAD HABIT SONG LIST Artist Song 4 Non Blondes Whats Up Alanis Morissette You Oughta Know Alanis Morissette Crazy Alanis Morissette You Learn Alanis Morissette Uninvited Alanis Morissette Thank You Alanis Morissette Ironic Alanis Morissette Hand In My Pocket Alice Merton No Roots Billie Eilish Bad Guy Bobby Brown My Prerogative Britney Spears Baby One More Time Bruno Mars Uptown Funk Bruno Mars 24K Magic Bruno Mars Treasure Bruno Mars Locked Out of Heaven Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey Christina Aguilera Fighter Corey Hart Sunglasses at Night Cyndi Lauper Time After Time David Guetta Titanium Deee-Lite Groove Is In The Heart Dishwalla Counting Blue Cars DNCE Cake By the Ocean Dua Lipa One Kiss Dua Lipa New Rules Dua Lipa Break My Heart Ed Sheeran Blow BAD HABIT SONG LIST Artist Song Elle King Ex’s & Oh’s En Vogue Free Your Mind Eurythmics Sweet Dreams Fall Out Boy Beat It George Michael Faith Guns N’ Roses Sweet Child O’ Mine Hailee Steinfeld Starving Halsey Graveyard Imagine Dragons Whatever It Takes Janet Jackson Rhythm Nation Jessie J Price Tag Jet Are You Gonna Be My Girl Jewel Who Will Save Your Soul Jo Dee Messina Heads Carolina, Tails California Jonas Brothers Sucker Journey Separate Ways Justin Timberlake Can’t Stop The Feeling Justin Timberlake Say Something Katy Perry Teenage Dream Katy Perry Dark Horse Katy Perry I Kissed a Girl Kings Of Leon Sex On Fire Lady Gaga Born This Way Lady Gaga Bad Romance Lady Gaga Just Dance Lady Gaga Poker Face Lady Gaga Yoü and I Lady Gaga Telephone BAD HABIT SONG LIST Artist Song Lady Gaga Shallow Letters to Cleo Here and Now Lizzo Truth Hurts Lorde Royals Madonna Vogue Madonna Into The Groove Madonna Holiday Madonna Border Line Madonna Lucky Star Madonna Ray of Light Meghan Trainor All About That Bass Michael Jackson Dirty Diana Michael Jackson Billie Jean Michael Jackson Human Nature Michael Jackson Black Or White Michael Jackson Bad Michael Jackson Wanna Be Startin’ Something Michael Jackson P.Y.T. -

Eminem 1 Eminem

Eminem 1 Eminem Eminem Eminem performing live at the DJ Hero Party in Los Angeles, June 1, 2009 Background information Birth name Marshall Bruce Mathers III Born October 17, 1972 Saint Joseph, Missouri, U.S. Origin Warren, Michigan, U.S. Genres Hip hop Occupations Rapper Record producer Actor Songwriter Years active 1995–present Labels Interscope, Aftermath Associated acts Dr. Dre, D12, Royce da 5'9", 50 Cent, Obie Trice Website [www.eminem.com www.eminem.com] Marshall Bruce Mathers III (born October 17, 1972),[1] better known by his stage name Eminem, is an American rapper, record producer, and actor. Eminem quickly gained popularity in 1999 with his major-label debut album, The Slim Shady LP, which won a Grammy Award for Best Rap Album. The following album, The Marshall Mathers LP, became the fastest-selling solo album in United States history.[2] It brought Eminem increased popularity, including his own record label, Shady Records, and brought his group project, D12, to mainstream recognition. The Marshall Mathers LP and his third album, The Eminem Show, also won Grammy Awards, making Eminem the first artist to win Best Rap Album for three consecutive LPs. He then won the award again in 2010 for his album Relapse and in 2011 for his album Recovery, giving him a total of 13 Grammys in his career. In 2003, he won the Academy Award for Best Original Song for "Lose Yourself" from the film, 8 Mile, in which he also played the lead. "Lose Yourself" would go on to become the longest running No. 1 hip hop single.[3] Eminem then went on hiatus after touring in 2005. -

Voice Dysphoria and the Transgender and Genderqueer Singer

What the Fach? Voice Dysphoria and the Transgender and Genderqueer Singer Loraine Sims, DMA, Associate Professor, Edith Killgore Kirkpatrick Professor of Voice, LSU 2018 NATS National Conference Las Vegas Introduction One size does not fit all! Trans Singers are individuals. There are several options for the singing voice. Trans woman (AMAB, MtF, M2F, or trans feminine) may prefer she/her/hers o May sing with baritone or tenor voice (with or without voice dysphoria) o May sing head voice and label as soprano or mezzo Trans man (AFAB, FtM, F2M, or trans masculine) may prefer he/him/his o No Testosterone – Probably sings mezzo soprano or soprano (with or without voice dysphoria) o After Testosterone – May sing tenor or baritone or countertenor Third Gender or Gender Fluid (Non-binary or Genderqueer) – prefers non-binary pronouns they/them/their or something else (You must ask!) o May sing with any voice type (with or without voice dysphoria) Creating a Gender Neutral Learning Environment Gender and sex are not synonymous terms. Cisgender means that your assigned sex at birth is in agreement with your internal feeling about your own gender. Transgender means that there is disagreement between the sex you were assigned at birth and your internal gender identity. There is also a difference between your gender identity and your gender expression. Many other terms fall under the trans umbrella: Non-binary, gender fluid, genderqueer, and agender, etc. Remember that pronouns matter. Never assume. The best way to know what pronouns someone prefers for themselves is to ask. In addition to she/her/hers and he/him/his, it is perfectly acceptable to use they/them/their for a single individual if that is what they prefer. -

2013 Victoria's Secret Fashion Show

PRESS ROOM EXCLUSIVELY FOR THE MEDIA THIS JUST IN… …from CBS Entertainment SEVEN-TIME GRAMMY® AWARD WINNER TAYLOR SWIFT AND GRAMMY AWARD-NOMINATED ARTIST FALL OUT BOY TO PERFORM ON “THE VICTORIA’S SECRET FASHION SHOW,” TUESDAY, DEC. 10 ON THE CBS TELEVISION NETWORK A Great Big World and UK Newcomers Neon Jungle Will Also Perform Seven-time GRAMMY® Award-winning artist Taylor Swift, GRAMMY Award-nominated artist Fall Out Boy, A Great Big World and Neon Jungle will perform on THE VICTORIA’S SECRET FASHION SHOW, to be broadcast Tuesday, Dec. 10 (10:00-11:00 PM, ET/PT) on the CBS Television Network. This year’s fashion show will include world-famous Victoria’s Secret Angels Adriana Lima, Alessandra Ambrosio, Lily Aldridge, Candice Swanepoel, Lindsay Ellingson, Karlie Kloss, Doutzen Kroes, Behati Prinsloo and many more. The lingerie runway show will also include pink carpet interviews, model profiles and a behind-the-scenes look at the making of the world’s most celebrated fashion show. Lauded by The New York Times as “one of the most important pop artists of the last decade,” and by Rolling Stone as “one of the few genuine rock stars we’ve got these days,” singer/songwriter Taylor Swift is a seven-time GRAMMY winner, and at 20, was the youngest winner in history of the music industry’s highest honor, the GRAMMY for Album of the Year in 2010. She is the only female artist in music history (and just the fourth artist ever) to twice have an album hit the one million first-week sales figure, and is the first artist since the Beatles (and the only female artist in history) to log six or more weeks at #1 with three consecutive studio albums. -

Developing the Young Dramatic Soprano Voice Ages 15-22 Is Approved in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Of

DEVELOPING THE YOUNG DRAMATIC SOPRANO VOICE AGES 15-22 By Monica Ariane Williams Bachelor of Arts – Vocal Arts University of Southern California 1993 Master of Music – Vocal Arts University of Southern California 1995 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music College of Fine Arts The Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas December 2020 Copyright 2021 Monica Ariane Williams All Rights Reserved Dissertation Approval The Graduate College The University of Nevada, Las Vegas November 30, 2020 This dissertation prepared by Monica Ariane Williams entitled Developing the Young Dramatic Soprano Voice Ages 15-22 is approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music Alfonse Anderson, DMA. Kathryn Hausbeck Korgan, Ph.D. Examination Committee Chair Graduate College Dean Linda Lister, DMA. Examination Committee Member David Weiller, MM. Examination Committee Member Dean Gronemeier, DMA, JD. Examination Committee Member Joe Bynum, MFA. Graduate College Faculty Representative ii ABSTRACT This doctoral dissertation provides information on how to develop the young dramatic soprano, specifically through more concentrated focus on the breath. Proper breathing is considered the single most important skill a singer will learn, but its methodology continues to mystify multitudes of singers and voice teachers. Voice professionals often write treatises with a chapter or two devoted to breathing, whose explanations are extremely varied, complex or vague. Young dramatic sopranos, whose voices are unwieldy and take longer to develop are at a particular disadvantage for absorbing a solid vocal technique. First, a description, classification and brief history of the young dramatic soprano is discussed along with a retracing of breath methodologies relevant to the young dramatic soprano’s development. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Karaoke Version Song Book

Karaoke Version Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID (Hed) Planet Earth 50 Cent Blackout KVD-29484 In Da Club KVD-12410 Other Side KVD-29955 A Fine Frenzy £1 Fish Man Almost Lover KVD-19809 One Pound Fish KVD-42513 Ashes And Wine KVD-44399 10000 Maniacs Near To You KVD-38544 Because The Night KVD-11395 A$AP Rocky & Skrillex & Birdy Nam Nam (Duet) 10CC Wild For The Night (Explicit) KVD-43188 I'm Not In Love KVD-13798 Wild For The Night (Explicit) (R) KVD-43188 Things We Do For Love KVD-31793 AaRON 1930s Standards U-Turn (Lili) KVD-13097 Santa Claus Is Coming To Town KVD-41041 Aaron Goodvin 1940s Standards Lonely Drum KVD-53640 I'll Be Home For Christmas KVD-26862 Aaron Lewis Let It Snow, Let It Snow, Let It Snow KVD-26867 That Ain't Country KVD-51936 Old Lamplighter KVD-32784 Aaron Watson 1950's Standard Outta Style KVD-55022 An Affair To Remember KVD-34148 That Look KVD-50535 1950s Standards ABBA Crawdad Song KVD-25657 Gimme Gimme Gimme KVD-09159 It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas KVD-24881 My Love, My Life KVD-39233 1950s Standards (Male) One Man, One Woman KVD-39228 I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus KVD-29934 Under Attack KVD-20693 1960s Standard (Female) Way Old Friends Do KVD-32498 We Need A Little Christmas KVD-31474 When All Is Said And Done KVD-30097 1960s Standard (Male) When I Kissed The Teacher KVD-17525 We Need A Little Christmas KVD-31475 ABBA (Duet) 1970s Standards He Is Your Brother KVD-20508 After You've Gone KVD-27684 ABC 2Pac & Digital Underground When Smokey Sings KVD-27958 I Get Around KVD-29046 AC-DC 2Pac & Dr.