Modal Politik Dan Kekuasaan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Symposium on Oral Education and Research in Kitakyushu

Asia-Pacific Conference in Fukuoka 2018 International Symposium on Oral Education and Research in Kitakyushu Date: May 11th 2018 (Fri) Venue: Kyushu Dental University, Kitakyushu, Japan Organized by Kyushu Dental University Asia-Pacific Conference in Fukuoka 2018 International Symposium on Oral Education and Research in Kitakyushu Kyushu Dental University, Kitakyushu, Japan May 11th, 2018 Organizing Committee: Tatsuji Nishihara, President Kenshi Maki Tetsuro Konoo Katsumi Hidaka Keisuke Nakashima Kou Matsuo Yuji Seta Tatsuo Kawamoto Hiroshi Takeuchi Atsuko Nakamichi Naoki Kakudate Wataru Ariyoshi Koji Watanabe Organized by Kyushu Dental University 1 Table of Contents Welcome message 3 Program 4 International Symposium 6 Congratulatory speeches by guests of honor 8 International Symposium 11 Partnership Activities of Kyushu Dental University with Universities in Myanmar 14 Poster Presentations 16 * Young Investigator Award Competition 16-31 2 3 Welcome message Tatsuji Nishihara, D.D.S., Ph.D. Chairman and President Kyushu Dental University Welcome to Asia-Pacific Conference in Fukuoka 2018. It is our great honor and pleasure to inform the International Symposium on Oral Education and Research in Kitakyushu. I am inviting you to participate in this exciting conference with valuable information on Oral Education and Research of Asia-Pacific countries. We are delighted to announce the special lectures in this conference. Present state of dental education in Asian countries as well as Myanmar will be introduced by the invited distinguished speaker, Professor Dr. Paing Soe, M.D., Ph.D., President of Myanmar Dental Council, The Republic of the Union of Myanmar. We are also very happy to hear on dental education system in Europe from Dr. -

Burma Coup Watch

This publication is produced in cooperation with Burma Human Rights Network (BHRN), Burmese Rohingya Organisation UK (BROUK), the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), Progressive Voice (PV), US Campaign for Burma (USCB), and Women Peace Network (WPN). BN 2021/2031: 1 Mar 2021 BURMA COUP WATCH: URGENT ACTION REQUIRED TO PREVENT DESTABILIZING VIOLENCE A month after its 1 February 2021 coup, the military junta’s escalation of disproportionate violence and terror tactics, backed by deployment of notorious military units to repress peaceful demonstrations, underlines the urgent need for substantive international action to prevent massive, destabilizing violence. The junta’s refusal to receive UN diplomatic and CONTENTS human rights missions indicates a refusal to consider a peaceful resolution to the crisis and 2 Movement calls for action confrontation sparked by the coup. 2 Coup timeline 3 Illegal even under the 2008 In order to avert worse violence and create the Constitution space for dialogue and negotiations, the 4 Information warfare movement in Burma and their allies urge that: 5 Min Aung Hlaing’s promises o International Financial Institutions (IFIs) 6 Nationwide opposition immediately freeze existing loans, recall prior 6 CDM loans and reassess the post-coup situation; 7 CRPH o Foreign states and bodies enact targeted 7 Junta’s violent crackdown sanctions on the military (Tatmadaw), 8 Brutal LIDs deployed Tatmadaw-affiliated companies and partners, 9 Ongoing armed conflict including a global arms embargo; and 10 New laws, amendments threaten human rights o The UN Security Council immediately send a 11 International condemnation delegation to prevent further violence and 12 Economy destabilized ensure the situation is peacefully resolved. -

San San Win, Dr

Dagon University Research Journal Vol.10 57 Political Development in Myanmar since 2011 San San Win 1 Abstract Since 2011, the new democratic government or semi-civilian government led by President U Thein Sein had conducted democratic reforms which ended fifty years of authoritarian rule. As a result, western countries lifted sanctions and provided economic assistance to Myanmar. Myanmar’s relations with western countries also improved significantly. Besides, under the civilian government since March 2016, a more open democratic environment has emerged. Despite existing challenges, the government has tried hard for democratic transactions under the leadership of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi. So, this paper focuses on political development in Myanmar since 2011 under the two democratic governments. Keywords: Myanmar, democracy, reforms, politics, development, relations Research Questions The research questions brought up for this paper are: How did Myanmar’s political culture change from authoritarian rule to democratic one? What are the basic causes for development of cordial relations with western countries? How did the situation of politics under the two democratic governments develop? And what are the challenges for both governments in nation building and foreign policy processes? Research Method This research will be conducted through critical analytical method. Most of the analysis will mainly refer to the newspapers of Myanmar, prior researches, books, periodicals, journals, website & online sources. Hypothesis Since 2011, Myanmar’s political culture peacefully changed from authoritarian rule to democratic one, and both the two democratic governments (USDP and NLD) tried to develop nation building, state building and foreign policy processes. Introduction Since early 2011, Myanmar has embarked on a remarkable path of political and economic reforms, departing from five decades of authoritarian rule. -

Elections in November: a Profile of Supporters of Myanmar's Ruling

ISSUE: 2020 No. 94 ISSN 2335-6677 RESEARCHERS AT ISEAS – YUSOF ISHAK INSTITUTE ANALYSE CURRENT EVENTS Singapore | 28 August 2020 Elections in November: A Profile of Supporters of Myanmar’s Ruling NLD Nyi Nyi Kyaw* EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • Partisanship is on the rise in the run-up to Myanmar’s 8 November 2020 general election. In this context, the typical supporter of the ruling National League for Democracy (NLD) party is often denigrated by critics and opposition forces as irrationally partisan. • Lumping together all NLD supporters as an irrational, partisan community overlooks the diversity among them. There are at least three types of NLD supporters: o the individually expressive supporters are partisans of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and the NLD; o the socially expressive supporters consider voting a social or civic duty; and o the instrumental voters point to the continued dominance of the military in Myanmar’s politics and the potential return of its proxy Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) as reasons for supporting for the NLD. • These three types of voters are not necessarily mutually exclusive; an expressive voter can at the same time be an instrumental voter. * Nyi Nyi Kyaw is Visiting Fellow in the Myanmar Studies Programme, ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, and Assistant Professor (adjunct) in the Department of Southeast Asian Studies, National University of Singapore. 1 ISSUE: 2020 No. 94 ISSN 2335-6677 INTRODUCTION In the past five years, the image of the supporter of Myanmar’s National League for Democracy (NLD) party and its chairwoman State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi has become rather tarnished. -

Atrocity Crimes Against Rohingya Muslims in Rakhine State, Myanmar

BEARING WITNESS REPORT NOVEMBER 2017 “THEY TRIED TO KILL US ALL” Atrocity Crimes against Rohingya Muslims in Rakhine State, Myanmar SIMON-SKJODT CENTER FOR THE PREVENTION OF GENOCIDE United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Washington, DC www.ushmm.org The United States Holocaust Museum’s work on genocide and related crimes against humanity is conducted by the Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide. The Simon-Skjodt Center is dedicated to stimulating timely global action to prevent genocide and to catalyze an international response when it occurs. Our goal is to make the prevention of genocide a core foreign policy priority for leaders around the world through a multipronged program of research, education, and public outreach. We work to equip decision makers, starting with officials in the United States but also extending to other governments and institutions, with the knowledge, tools, and institutional support required to prevent— or, if necessary, halt—genocide and related crimes against humanity. FORTIFY RIGHTS Southeast Asia www.fortifyrights.org Fortify Rights works to ensure and defend human rights for all. We investigate human rights violations, engage policy makers and others, and strengthen initiatives led by human rights defenders, affected communities, and civil society. We believe in the influence of evidence- based research, the power of strategic truth-telling, and the importance of working closely with individuals, communities, and movements pushing for change. We are an independent, nonprofit organization based in Southeast Asia and registered in the United States and Switzerland. The United State Holocaust Memorial Museum uses the name “Burma” and Fortify Rights uses the name “Myanmar” to describe the same country. -

2017 Myanmar By-Elections IEOM Report

1 2017 Myanmar By-Elections: A Path to Myanmar’s 2020 General Election Final Report of the International Election Observation Mission (IEOM) of the 2017 By-Elections in the Republic of the Union of Myanmar 2 Written by : Ryan D Whelan, Dr. Aulina Adamy, Amin Iskandar, Ichal Supriadi, Chandanie Watawala Edited by : Ryan D Whelan, George Rothschild, Karel J Galang Layout by : Sann Moe Aung Book cover designed by : Sann Moe Aung Printer : Mr.Print (Design & Printing) Photos without credits are courtesy of ANFREL mission observers The Asian Network for Free Elections (ANFREL) 105, Susthisarnwinichai Road, Samsennok, Huaykwang, Bangkok 10310, Thailand. Tel: (+66 2) 26931867 Email : [email protected] Website : www.anfrel.org ISBN : 978-616-90144-61 2017, Yangon, Myanmar This report reflects the holistic findings of the ANFREL Observation Mission in Myanmar and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of any of ANFREL’s individual observers, staff, donors, or CSO partners. No institution, nor a person acting on its behalf, shall be held responsible for the information contained herein. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. 3 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The mission would like to thank the committed International Election Observers, whose hard work informed the production of this report. Their dedication to both their observation and our democratic mission is an encouraging sign for democracy’s continued growth in Asia. ANFREL is similarly grateful for the dozens of local staff members who generously gave their time and energy to make the mission a success, often having to overcome significant challenges encountered along the way. ANFREL would also like to thank the Union Election Commission of Myanmar, government officials, as well as candidates and representatives of political parties, civil society groups, and the media in Myanmar for the warm welcome and cooperation provided to ANFREL and its observers. -

Myanmar Maneuvers How to Break Political-Criminal Alliances in Contexts of Transition

United Nations University Centre for Policy Research Crime-Conflict Nexus Series: No 9 April 2017 Myanmar Maneuvers How to Break Political-Criminal Alliances in Contexts of Transition Dr. Vanda Felbab-Brown Senior Fellow, The Brookings Institution This material has been funded by UK aid from the UK government; however the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies. © 2017 United Nations University. All Rights Reserved. ISBN 978-92-808-9040-2 Myanmar Maneuvers How to Break Political-Criminal Alliances in Contexts of Transition 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Myanmar case study analyzes the complex interactions between illegal economies -conflict and peace. Particular em- phasis is placed on understanding the effects of illegal economies on Myanmar’s political transitions since the early 1990s, including the current period, up through the first year of the administration of Aung San Suu Kyi. Described is the evolu- tion of illegal economies in drugs, logging, wildlife trafficking, and gems and minerals as well as land grabbing and crony capitalism, showing how they shaped and were shaped by various political transitions. Also examined was the impact of geopolitics and the regional environment, particularly the role of China, both in shaping domestic political developments in Myanmar and dynamics within illicit economies. For decades, Burma has been one of the world’s epicenters of opiate and methamphetamine production. Cultivation of poppy and production of opium have coincided with five decades of complex and fragmented civil war and counterinsur- gency policies. An early 1990s laissez-faire policy of allowing the insurgencies in designated semi-autonomous regions to trade any products – including drugs, timber, jade, and wildlife -- enabled conflict to subside. -

Myanmar | Identifying Major Labour Policy Issues in Myanmar, Japan

Myanmar Identifying Major Labour Policy Issues in Myanmar I. Summary II. The changing features of industrial sectors, business Eitra MYO organizations and business activities SAGA Asia Consulting Company Ltd. III. The changing features of working relations, work organizations and working styles IV. Background factors V. Major issues of labour policies I. Summary Labour Law reform in Myanmar has been initiated since 2011 as an effect of political and economic policy reform and open to international collaboration and economic integration. Prominent policy reforms which change the landscape of industrial relations and labour market are systemic labour dispute resolution mechanism, new labour organisation law, new social security system, stipulation on compulsory employment contract and minimum wage rate and so on. However, Myanmar labour market faces many major labour issues such as skill shortage, mismatch of education and labour market demands, weakness on labour law enforcement, limited social security coverage and awareness building on labour laws and regulations. II The changing features of industrial sectors, business organisations and business activities The economy of Myanmar had been predominated based on agriculture sector since 1990s.1 After 2000, the GDP share of manufacturing and service sectors constantly increased. In 2014-2015, manufacturing sector contributed 34% of GDP and service and agriculture sector are 32% and 17% respectively.2 According to the Myanmar Enterprise Survey 2014, there are 632 registered enterprises in -

Myanmar Politics & People in 2015

Myanmar Politics & People in 2015 Myanmar Politics & People in 2015 1. Background ..........................................................................................................................................3 2. Political Structure ................................................................................................................................4 3. Political System ....................................................................................................................................4 4. Issues ....................................................................................................................................................5 4.1. Peace ..........................................................................................................................................................................5 4.2. Economy ...................................................................................................................................................................6 4.3. Constitutional Amendment ...............................................................................................................................7 4.4. Land ............................................................................................................................................................................7 4.5. Sanctions ..................................................................................................................................................................7 -

Burma, Buddhism, and Aung San Suu Kyi

Lindsey Dean Dominican University of California NEH Institute on Southeast Asia, Summer 2011 Course Module The Philosophy of Nonviolence: Burma, Buddhism, and Aung San Suu Kyi Introduction This lesson introduces students to a Buddhist philosophy of nonviolence through an examination of the social ethics and strategies that have been employed by the people of Burma/Myanmar in their fight for freedom, legitimate political authority, and social justice during the reign of the county's military regime. Drawing on their knowledge from a previous session on the work of Gandhi and the Indian Independence Movement, students will analyze suttas from the Digha Nikaya (The Long Discourses of the Buddha) and the speeches and writing of Aung San Suu Kyi in order to become acquainted with key Buddhist ideas and their application in nonviolent action, particularly during the 8-8-88 demonstrations and the “Saffron Revolution.” Students will also consider the potential of nonviolence in relation to projections for Burma's social, political and cultural future. Guiding Questions • What social, economic, political, and religious developments have taken place in Burma from the time of independence to the present? • How are we to understand the structural violence that exists in the state of Burma/Myanmar? • How has Buddhism influenced social-ethical values and conceptions of legitimate political authority in Burma? How has Buddhism been employed by the junta as a means of social control? • What role does vipassina play in a revolution of spirit and a culture -

Military and Democracy in Myanmar

79\12 12 December 2012 MILITARY AND DEMOCRACY IN MYANMAR Lt Col Mohinder Pal Singh Dept of Defence And Strategic Studies, University of Allahabad Aung San Suu Kyi’s visit to India in November, 2012 has The Demographic Matrix opened a new chapter in Indo – Myanmar relations. India has Demographically, the country is divided into various ethnic been an active supporter of pro-democratic movement in groups. 68% population comprise of Burmans which dominate Myanmar had earlier triedto engage the Military junta through the central low land region. The other important ethnic groups her look ‘Look East Policy’. By allowing it the ASEAN are Shan, Karen, Mon, Karenni, Kachin, Rohignya, Wa, Chin and membership, India not only prevented the complete isolation Rakhine which are confined to high land periphery. Their share of Myanmar but also saved it from falling prey to non- in population are 9%, 7%, 2%,.75%, 1.5% .15% .16%, 2.5% democratic governance model. This visit of the opposition and 3.5%, respectively. leader can be seen as a positive development for the future of With the departure of the Britishers from Myanmar, an agreement, both the countries. The problem that arises is that in the coming known as Panlong Agreement, was signed between the years India has to choose between the pro-democratic forces government under Aung Sanand the representatives of Shan, and the present military regime. It is in this context the study of Kachin and Chin on12 February1947. It agreed on the principle Myanmar’s militarised democracy becomes important in of “full autonomy” in internal administration for the Frontier understanding its relations not only with India but also with Areas” and the creation of a Kachin State by the Constituent other democratic countries. -

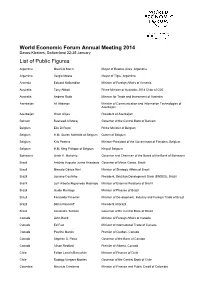

List of Public Figures

World Economic Forum Annual Meeting 2014 Davos-Klosters, Switzerland 22-25 January List of Public Figures Argentina Mauricio Macri Mayor of Buenos Aires, Argentina Argentina Sergio Massa Mayor of Tigre, Argentina Armenia Edward Nalbandian Minister of Foreign Affairs of Armenia Australia Tony Abbott Prime Minister of Australia; 2014 Chair of G20 Australia Andrew Robb Minister for Trade and Investment of Australia Azerbaijan Ali Abbasov Minister of Communication and Information Technologies of Azerbaijan Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev President of Azerbaijan Bahrain Rasheed Al Maraj Governor of the Central Bank of Bahrain Belgium Elio Di Rupo Prime Minister of Belgium Belgium H.M. Queen Mathilde of Belgium Queen of Belgium Belgium Kris Peeters Minister-President of the Government of Flanders, Belgium Belgium H.M. King Philippe of Belgium King of Belgium Botswana Linah K. Mohohlo Governor and Chairman of the Board of the Bank of Botswana Brazil Antônio Augusto Junho Anastasia Governor of Minas Gerais, Brazil Brazil Marcelo Côrtes Neri Minister of Strategic Affairs of Brazil Brazil Luciano Coutinho President, Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES), Brazil Brazil Luiz Alberto Figueiredo Machado Minister of External Relations of Brazil Brazil Guido Mantega Minister of Finance of Brazil Brazil Fernando Pimentel Minister of Development, Industry and Foreign Trade of Brazil Brazil Dilma Rousseff President of Brazil Brazil Alexandre Tombini Governor of the Central Bank of Brazil Canada John Baird Minister of Foreign Affairs of Canada Canada Ed Fast Minister