Testimony Interviewee Cards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[Pdf] Annette Weinke Background of the Judicial Process of Coming to Terms with The](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6142/pdf-annette-weinke-background-of-the-judicial-process-of-coming-to-terms-with-the-176142.webp)

[Pdf] Annette Weinke Background of the Judicial Process of Coming to Terms with The

www.wollheim-memorial.de Annette Weinke Background of the Judicial Process of “Coming to Terms with” the Buna/Monowitz Concentration Camp Possibilities, Problems, and Limits Allied Prosecution . 1 Wave of Amnesty and Civil Actions . 13 German-German Criminal Prosecution . 20 Norbert Wollheim Memorial J.W. Goethe-Universität / Fritz Bauer Institut Frankfurt am Main, 2010 www.wollheim-memorial.de Annette Weinke: Background of the Judicial Process, p. 1 Allied Prosecution On November 13, 1948, a good three months after the beginning of the trial of 24 board members and executives of the I.G. Farben conglomerate—one of the Subsequent Nuremberg Trials—Norbert Wollheim was cross-examined before American Military Tribunal VI.1 Because the former Monowitz prisoner, in one of his affidavits, had previously stated that the foremen of Mannesmann Röhren- werke, a Berlin-based manufacturer of seamless steel tubes, had treated their Jewish forced laborers for the most part with a certain sympathy and considera- tion, he now was requested to describe his experiences with the I.G. Farben per- sonnel. Wollheim indicated that not only had the Farben people been heavily op- posed to Jews and other concentration camp inmates, but they had even been chosen for work in Auschwitz for that very reason. Wollheim recalled one incident when several foremen, together with a kapo, had thrashed a Dutch Jew so badly that he died of his injuries. In response, the presiding judge asked whether Woll- heim believed that the Farben management had instructed its employees or al- lowed them to beat concentration camp inmates to death. Wollheim‘s reply was that there had been no need for a specific directive, as all the prisoners, regard- less of nationality or level of education, were beaten constantly. -

Syntactic Structure in Memory

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses April 2021 There and Gone Again: Syntactic Structure In Memory Caroline Andrews University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the Psycholinguistics and Neurolinguistics Commons Recommended Citation Andrews, Caroline, "There and Gone Again: Syntactic Structure In Memory" (2021). Doctoral Dissertations. 2090. https://doi.org/10.7275/19826911 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/2090 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses There and Gone Again: Syntactic Structure In Memory Caroline Andrews Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the Psycholinguistics and Neurolinguistics Commons THERE AND GONE AGAIN: SYNTACTIC STRUCTURE IN MEMORY A Dissertation Presented by CAROLINE ANDREWS Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 2021 Linguistics c Copyright by Caroline Andrews 2021 All Rights Reserved THERE AND GONE AGAIN: SYNTACTIC STRUCTURE IN MEMORY A Dissertation Presented by CAROLINE ANDREWS Approved as to style and content by: Brian Dillon, Chair John Kingston, Member Adrian Staub, Member Joe Pater, Department Chair Linguistics To my parents and my brother, who have taught me so many things, not the least of which were courage and curiosity. -

PATTI SMITH Eighteen Stations MARCH 3 – APRIL 16, 2016

/robertmillergallery For immediate release: [email protected] @RMillerGallery 212.366.4774 /robertmillergallery PATTI SMITH Eighteen Stations MARCH 3 – APRIL 16, 2016 New York, NY – February 17, 2016. Robert Miller Gallery is pleased to announce Eighteen Stations, a special project by Patti Smith. Eighteen Stations revolves around the world of M Train, Smith’s bestselling book released in 2015. M Train chronicles, as Smith describes, “a roadmap to my life,” as told from the seats of the cafés and dwellings she has worked from globally. Reflecting the themes and sensibility of the book, Eighteen Stations is a meditation on the act of artistic creation. It features the artist’s illustrative photographs that accompany the book’s pages, along with works by Smith that speak to art and literature’s potential to offer hope and consolation. The artist will be reading from M Train at the Gallery throughout the run of the exhibition. Patti Smith (b. 1946) has been represented by Robert Miller Gallery since her joint debut with Robert Mapplethorpe, Film and Stills, opened at its 724 Fifth Avenue location in 1978. Recent solo exhibitions at the Gallery include Veil (2009) and A Pythagorean Traveler (2006). In 2014 Rockaway Artist Alliance and MoMA PS1 mounted Patti Smith: Resilience of the Dreamer at Fort Tilden, as part of a special project recognizing the ongoing recovery of the Rockaway Peninsula, where the artist has a home. Smith's work has been the subject of solo exhibitions at institutions worldwide including the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto (2013); Detroit Institute of Arts (2012); Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford (2011); Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporaine, Paris (2008); Haus der Kunst, Munich (2003); and The Andy Warhol Museum (2002). -

Norbert Wollheim Memorial Und an Der Heutigen Eröffnung Mitwirken

2. November 2009 212a Herausgeber: Der Präsident Redaktion: Stephan M. Hübner Pressereferent Telefon (069) 798-23753 Rede von Staatsministerin Silke Telefax (069) 798-28530 E-Mail: [email protected] Lautenschläger Senckenberganlage 31 60325 Frankfurt am Main anlässlich der Eröffnung des Norbert Wollheim Memorial Frau Wollheim Wachter-Carroll, Herr Professor Wollheim, Herr Kimmelstiel – und mit Ihnen alle Überlebenden der IG Auschwitz, die heute aus vielen Ländern der Erde hierher nach Frankfurt gekommen sind. Im Namen der Hessischen Landesregierung Ihnen und Ihren Angehörigen ein herzliches Willkommen! Ich grüße die Mitglieder des Magistrats der Stadt Frankfurt am Main, die Mandatsträger aus dem Deutschen Bundestag, aus dem Hessischen Landtag, aus dem Frankfurter Stadtparlament und aus den Ortsbeiräten, die Mitglieder des Konsularischen Corps, die Vertreterinnen und Vertreter der Jüdischen Gemeinde, der Kirchen und der Gewerkschaften, ich grüße Herrn Professor Blum und mit ihm alle, die an der Realisierung des Norbert Wollheim Memorial und an der heutigen Eröffnung mitwirken. Nicht zuletzt begrüße ich Herrn Kagan, langjähriger Leiter der Claims Conference in New York, und mit ihm alle Mäzene und Sponsoren, ohne deren großzügige Hilfe wir das Norbert Wollheim Memorial heute nicht eröffnen könnten. Herr Präsident, Frau Simonsohn, Herr Mangelsdorff, meine Damen und Herren! Meine Grüße an Sie alle verbinden sich mit meinem Dank - dem ganz persönlichen Dank einer hessischen Staatsministerin an eine weltweite Bürgerinitiative gegen das Vergessen. Denn einzigartig ist am Norbert Wollheim Memorial nicht nur die glückliche Verbindung von künstlerischer Aussage, wissenschaftlicher Aufklärung und pädagogischer Arbeit, einzigartig ist auch seine Entstehungsgeschichte. Ich will sie uns allen in Erinnerung rufen: Im Oktober 1998 trafen sich die Überlebenden der IG Auschwitz zum ersten Mal hier auf dem früheren Gelände des IG Farben-Konzerns, der für tausendfachen Tod und unermessliches Leid verantwortlich gewesen ist. -

Anne Frank: the Commemoration of Individual Experiences of the Holocaust

Journalism and Mass Communication, September 2016, Vol. 6, No. 9, 542-554 doi: 10.17265/2160-6579/2016.09.004 D DAVID PUBLISHING Anne Frank: The Commemoration of Individual Experiences of the Holocaust Rudi Hartmann University of Colorado Denver, Denver, USA Holocaust memorial sites rarely tell the story of individual fates but rather give attention to the main or larger population groups that were the focus of persecution and extermination during the Nazi Germany twelve years of terror in Europe 1933-45. This essay takes a closer look at one of the most remarkable exemptions of the prevailing memory culture at Holocaust memorials: the sites and events highlighting Anne Frank and her short life in troubled times. Over the past years millions of travelers from all over the world have shown a genuine interest in learning about the life world of their young heroine thus creating what has been termed Anne Frank Tourism. In 2014, 1.2 million people visited the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam: the museum and educational center, the place in hiding where she wrote her now famous and widely read diary. Several other sites connected to the life path of Anne Frank, from her birth place in Frankfurt to the Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp where her life prematurely ended, have also become part of the mostly young tourists’ search for Anne Frank’s life and legacy. With the rising popularity of Anne Frank related sites the management of some of the locales has become more problematic which is discussed in the context of a several museums, centers and historic sites. -

NEW MUSIC on COMPACT DISC 4/16/04 – 8/31/04 Amnesia

NEW MUSIC ON COMPACT DISC 4/16/04 – 8/31/04 Amnesia / Richard Thompson. AVRDM3225 Flashback / 38 Special. AVRDM3226 Ear-resistible / the Temptations. AVRDM3227 Koko Taylor. AVRDM3228 Like never before / Taj Mahal. AVRDM3229 Super hits of the '80s. AVRDM3230 Is this it / the Strokes. AVRDM3231 As time goes by : great love songs of the century / Ettore Stratta & his orchestra. AVRDM3232 Tiny music-- : songs from the Vatican gift shop / Stone Temple Pilots. AVRDM3233 Numbers : a Pythagorean theory tale / Cat Stevens. AVRDM3234 Back to earth / Cat Stevens. AVRDM3235 Izitso / Cat Stevens. AVRDM3236 Vertical man / Ringo Starr. AVRDM3237 Live in New York City / Bruce Springsteen & the E Street Band. AVRDM3238 Dusty in Memphis / Dusty Springfield. AVRDM3239 I'll be around : and other hits. AVRDM3240 No one does it better / SoulDecision. AVRDM3241 Doin' something / Soulive. AVRDM3242 The very thought of you: the Decca years, 1951-1957 /Jeri Southern. AVRDM3243 Mighty love / Spinners. AVRDM3244 Candy from a stranger / Soul Asylum. AVRDM3245 Gone again / Patti Smith. AVRDM3246 Gung ho / Patti Smith. AVRDM3247 Freak show / Silverchair. AVRDM3248 '60s rock. The beat goes on. AVRDM3249 ‘60s rock. The beat goes on. AVRDM3250 Frank Sinatra sings his greatest hits / Frank Sinatra. AVRDM3251 The essence of Frank Sinatra / Frank Sinatra. AVRDM3252 Learn to croon / Frank Sinatra & Tommy Dorsey and his orchestra. AVRDM3253 It's all so new / Frank Sinatra & Tommy Dorsey and his orchestra. AVRDM3254 Film noir / Carly Simon. AVRDM3255 '70s radio hits. Volume 4. AVRDM3256 '70s radio hits. Volume 3. AVRV3257 '70s radio hits. Volume 1. AVRDM3258 Sentimental favorites. AVRDM3259 The very best of Neil Sedaka. AVRDM3260 Every day I have the blues / Jimmy Rushing. -

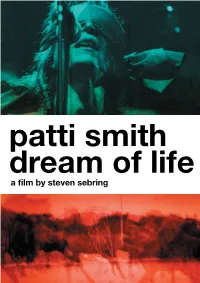

Patti DP.Indd

patti smith dream of life a film by steven sebring THIRTEEN/WNET NEW YORK AND CLEAN SOCKS PRESENT PATTI SMITH AND THE BAND: LENNY KAYE OLIVER RAY TONY SHANAHAN JAY DEE DAUGHERTY AND JACKSON SMITH JESSE SMITH DIRECTORS OF TOM VERLAINE SAM SHEPARD PHILIP GLASS BENJAMIN SMOKE FLEA DIRECTOR STEVEN SEBRING PRODUCERS STEVEN SEBRING MARGARET SMILOW SCOTT VOGEL PHOTOGRAPHY PHILLIP HUNT EXECUTIVE CREATIVE STEVEN SEBRING EDITORS ANGELO CORRAO, A.C.E, LIN POLITO PRODUCERS STEVEN SEBRING MARGARET SMILOW CONSULTANT SHOSHANA SEBRING LINE PRODUCER SONOKO AOYAGI LEOPOLD SUPERVISING INTERNATIONAL PRODUCERS JUNKO TSUNASHIMA KRISTIN LOVEJOY DISTRIBUTION BY CELLULOID DREAMS Thirteen / WNET New York and Clean Socks present Independent Film Competition: Documentary patti smith dream of life a film by steven sebring USA - 2008 - Color/B&W - 109 min - 1:66 - Dolby SRD - English www.dreamoflifethemovie.com WORLD SALES INTERNATIONAL PRESS CELLULOID DREAMS INTERNATIONAL HOUSE OF PUBLICITY 2 rue Turgot Sundance office located at the Festival Headquarters 75009 Paris, France Marriott Sidewinder Dr. T : + 33 (0) 1 4970 0370 F : + 33 (0) 1 4970 0371 Jeff Hill – cell: 917-575-8808 [email protected] E: [email protected] www.celluloid-dreams.com Michelle Moretta – cell: 917-749-5578 E: [email protected] synopsis Dream of Life is a plunge into the philosophy and artistry of cult rocker Patti Smith. This portrait of the legendary singer, artist and poet explores themes of spirituality, history and self expression. Known as the godmother of punk, she emerged in the 1970’s, galvanizing the music scene with her unique style of poetic rage, music and trademark swagger. -

2012 U.S. Banking Sector Outlook: Happy Days Are Gone Again 2012 U.S

December 2011 ® 2012 U.S. Banking Sector Outlook: Happy Days Are Gone Again 2012 U.S. Banking Sector Outlook: Happy Days Are Gone Again TABLE OF CONTENTS 2012 OutlooK Executive Summary ............................................................................................................. 1 EARNINGS Profits will slump after strong 2011 ...................................................................................... 3 NET INTEREst MARGINS A flat yield curve and anemic loan growth add up to eroding margins in 2012 .................... 4 BANK FEE REVENUE Banks face difficulty in replacing lost fee income ............................................................... 5 LOSS PROVISIONING End of the line for the loss allowance “release” .................................................................. 7 U.S. BANK BALANCE SHEET TRENDS Risk appetite lacking ............................................................................................................. 8 EUROPEAN EXPOSURES Downside risks, but not life-threatening .............................................................................. 10 COMMERCIAL REAL EstatE More bumps in the road as liquidity remains tight, could get worse ................................... 12 REgulatoRY ENVIRONMENT Life for banks gets more complicated .................................................................................. 14 BANK DIstRESS U.S. bank failure cycle far from over, more than 200 banks at high risk of failure ................ 17 Trepp, LLC Table of Contents 2012 U.S. -

I.G. Farben's Petro-Chemical Plant and Concentration Camp at Auschwitz Robert Simon Yavner Old Dominion University

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons History Theses & Dissertations History Summer 1984 I.G. Farben's Petro-Chemical Plant and Concentration Camp at Auschwitz Robert Simon Yavner Old Dominion University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/history_etds Part of the Economic History Commons, and the European History Commons Recommended Citation Yavner, Robert S.. "I.G. Farben's Petro-Chemical Plant and Concentration Camp at Auschwitz" (1984). Master of Arts (MA), thesis, History, Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/7cqx-5d23 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/history_etds/27 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the History at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1.6. FARBEN'S PETRO-CHEMICAL PLANT AND CONCENTRATION CAMP AT AUSCHWITZ by Robert Simon Yavner B.A. May 1976, Gardner-Webb College A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS HISTORY OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY August 1984 Approved by: )arw±n Bostick (Director) Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Copyright by Robert Simon Yavner 1984 All Rights Reserved Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ABSTRACT I.G. FARBEN’S PETRO-CHEMICAL PLANT AND CONCENTRATION CAMP AT AUSCHWITZ Robert Simon Yavner Old Dominion University, 1984 Director: Dr. Darwin Bostick This study examines the history of the petro chemical plant and concentration camp run by I.G. -

Katalog, Einzelseiten

Begleitpublikation Die I.G. Farben und das Konzentrationslager Buna-Monowitz | Inhaltsverzeichnis Inhaltsverzeichnis Geleitwort 5 DIE ERRICHTUNG DES KONZENTRATIONSLAGERS 7 BUNA-MONOWITZ 1. Was war die I.G. Farben? 8 2. Die Gründung der I.G. Auschwitz im April 1942 10 3. Das Konzentrationslager Auschwitz 14 4. Zwangsarbeiter bei der I.G. Auschwitz 16 5. Die SS 20 6. Die Mitarbeiter der I.G. Farben 24 DIE HÄFTLINGE IM KONZENTRATIONSLAGER 28 BUNA-MONOWITZ 7. Deportation 30 8. Ankunft 34 9. Zwangsarbeit 37 10. Fachleute 40 11. Hierarchien unter den Häftlingen 42 12. Willkür und Misshandlungen 45 13. Verpflegung 47 14. Hygiene 48 15. Krankheit 50 16. Selektion – Die »Auswahl zum Tode« 53 Die I.G. Farben und das Konzentrationslager Buna-Monowitz | Inhaltsverzeichnis 3 17. Widerstand 56 18. Bombenangriffe 59 19. Todesmärsche 61 20. Befreiung 64 21. Die Zahlen der Toten 66 DIE I.G. FARBEN NACH 1945 UND DIE JURISTISCHE 67 AUFARBEITUNG IHRER VERBRECHEN 22. Die I.G. Farben nach 1945 68 23. Der Nürnberger Prozess gegen die I.G. Farben 70 (1947/48) 24. Die Urteile im Nürnberger Prozess 72 25. Der Wollheim-Prozess 76 (1951 – 1957) 26. Aussagen aus dem Wollheim-Prozess 78 (1951 – 1957) 27. Frankfurter Auschwitz-Prozesse 80 (1963 – 1967) 28. Die politische Vereinnahmung des 81 Fischer-Prozesses durch das SED-Regime 29. Das Ende der I.G. Farben i.L. 82 (1990 – 2003) Impressum 85 4 5 Geleitwort Die I.G. Farben und das Konzentrationslager Buna-Monowitz Wirtschaft und Politik im Nationalsozialismus ZUR AUSSTELLUNG Der Chemiekonzern I.G. Farben ließ ab 1941 in unmittelbarer Nähe zum Konzen- trationslager Auschwitz eine chemische Fabrik bauen, die größte im von Deutsch- land während des Zweiten Weltkriegs eroberten Osteuropa. -

The Salvation of the Kindertransport: a Ray of Hope for Nearly Ten

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Honors Theses University Honors Program 5-2003 The alS vation of the Kindertransport: a Ray of Hope for Nearly Ten Thousand Jewish Children Cheryl Holder Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/uhp_theses Recommended Citation Holder, Cheryl, "The alvS ation of the Kindertransport: a Ray of Hope for Nearly Ten Thousand Jewish Children" (2003). Honors Theses. Paper 251. This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the University Honors Program at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cheryl Holder Professor Thomas Thibeault UHON 499, Section 701 (Honors Thesis) 9 May 2003 The Salvation ofthe Kindertransport: A Ray ofHope for Nearly Ten Thousand Jewish Children INTRODUCTION From the beginning oftime, humanity has seen conflicts, uprisings and wars between cultures, religions and boundaries making the world a continual battlefield throughout its existence. At one time or another the entire world at some point has witnessed the brunt of these continual paths ofdestruction and horror. And over time, these conflicts have originated for different reasons: acquiring wealth and additional land mass, hatred or greed against a culture, taking control over the weak, political and religious beliefs, protection of an existing culture or lifestyle, fear, revenge or retaliation, and bad judgment. These wars are never initiated by the innocent ofthe world, especially the children, but are forced upon them in such brutal ways that it is hard to fathom that mankind at times can be so insanely cruel, unjust and incomprehensible to their very existence or plight. -

NOISE DIARY ---- Shirley Nelson, Lowell Vermont January 2013 – March 2014

NOISE DIARY ---- Shirley Nelson, Lowell Vermont January 2013 – March 2014 (wind direction notes are from the turbine direction – may times the wind was not blowing here and many times if the wind is blowing here the turbines weren't turning) 1-1-13 nothing running T7 still sideways ice on blades of many later some turning verrrrrrry slowly 1-2-13 nothing turning 7:00 am nothing turning at noon- still look ice covered – the top third of the mountain is covered with ice- we had told them that the mountain top was often covered with ice for up to three weeks or more at a time afternoon – T1-6 running slowly guy here to change batteries in monitors – Barney barking like an idiot 4:15 T 1-4 turned off T5+6 still on T7 still facing south - first 6 are facing N-NW south of T7 are facing west Clouds have been whipping over the mountain and trees down here aren't moving Guy came in – said he couldn't get one unlocked – I suggested hand warmers- he said it might work but was heading for a propane torch Said he is from Wilder – their main office is in White River – another in Burlington and in Ohio and out west …... he is leaving the monitors again because something wasn't right the first time – he was in Lowell from 11:00 till 2:00 GMP told him that they are running them for 3 hours at a time (haven't figured that out yet – they haven't done it during the day for some time ) 5:00 pm T5 and 6 are off again 1-3-13 nothing moving T7 hasn't turned back and forth yet 11:15 nothing moved yet noon – nothing turning beautiful out – cold but sunny – NO WIND T5and T10 have turned to the west – maybe T13 turning to west???? went to Press conference in Montpelier met the RSG guy leaving when we came home back home and nothing turning tonight Janet left message saying she thought blades on T3 looked broken when she came home from Irasburg- dark enough so we couldn't tell 1-4-13 2 wind from W-SW 20 deg.