The Women of Othello Heather Crabbe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Otello Program

GIUSEPPE VERDI otello conductor Opera in four acts Gustavo Dudamel Libretto by Arrigo Boito, based on production Bartlett Sher the play by William Shakespeare set designer Thursday, January 10, 2019 Es Devlin 7:30–10:30 PM costume designer Catherine Zuber Last time this season lighting designer Donald Holder projection designer Luke Halls The production of Otello was made possible by revival stage director Gina Lapinski a generous gift from Jacqueline Desmarais, in memory of Paul G. Desmarais Sr. The revival of this production is made possible by a gift from Rolex general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2018–19 SEASON The 345th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIUSEPPE VERDI’S otello conductor Gustavo Dudamel in order of vocal appearance montano a her ald Jeff Mattsey Kidon Choi** cassio lodovico Alexey Dolgov James Morris iago Željko Lučić roderigo Chad Shelton otello Stuart Skelton desdemona Sonya Yoncheva This performance is being broadcast live on Metropolitan emilia Opera Radio on Jennifer Johnson Cano* SiriusXM channel 75 and streamed at metopera.org. Thursday, January 10, 2019, 7:30–10:30PM KEN HOWARD / MET OPERA Stuart Skelton in Chorus Master Donald Palumbo the title role and Fight Director B. H. Barry Sonya Yoncheva Musical Preparation Dennis Giauque, Howard Watkins*, as Desdemona in Verdi’s Otello J. David Jackson, and Carol Isaac Assistant Stage Directors Shawna Lucey and Paula Williams Stage Band Conductor Gregory Buchalter Prompter Carol Isaac Italian Coach Hemdi Kfir Met Titles Sonya Friedman Children’s Chorus Director Anthony Piccolo Assistant Scenic Designer, Properties Scott Laule Assistant Costume Designers Ryan Park and Wilberth Gonzalez Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted in Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes executed by Metropolitan Opera Costume Department; Angels the Costumiers, London; Das Gewand GmbH, Düsseldorf; and Seams Unlimited, Racine, Wisconsin Wigs and Makeup executed by Metropolitan Opera Wig and Makeup Department This production uses strobe effects. -

Verdi Otello

VERDI OTELLO RICCARDO MUTI CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ALEKSANDRS ANTONENKO KRASSIMIRA STOYANOVA CARLO GUELFI CHICAGO SYMPHONY CHORUS / DUAIN WOLFE Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) OTELLO CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA RICCARDO MUTI 3 verdi OTELLO Riccardo Muti, conductor Chicago Symphony Orchestra Otello (1887) Opera in four acts Music BY Giuseppe Verdi LIBretto Based on Shakespeare’S tragedy Othello, BY Arrigo Boito Othello, a Moor, general of the Venetian forces .........................Aleksandrs Antonenko Tenor Iago, his ensign .........................................................................Carlo Guelfi Baritone Cassio, a captain .......................................................................Juan Francisco Gatell Tenor Roderigo, a Venetian gentleman ................................................Michael Spyres Tenor Lodovico, ambassador of the Venetian Republic .......................Eric Owens Bass-baritone Montano, Otello’s predecessor as governor of Cyprus ..............Paolo Battaglia Bass A Herald ....................................................................................David Govertsen Bass Desdemona, wife of Otello ........................................................Krassimira Stoyanova Soprano Emilia, wife of Iago ....................................................................BarBara DI Castri Mezzo-soprano Soldiers and sailors of the Venetian Republic; Venetian ladies and gentlemen; Cypriot men, women, and children; men of the Greek, Dalmatian, and Albanian armies; an innkeeper and his four servers; -

Bianca and Cassio's Relationship in <Em>Othello</Em>

Marquette University From the SelectedWorks of Sarah E. Thompson 2012 "I Am No Strumpet": Bianca and Cassio's Relationship in <em>Othello</em> Sarah E. Thompson, Marquette University Available at: https://works.bepress.com/sarah_thompson/1/ 1 Sarah Thompson English 6220 December 12, 2012 “I Am No Strumpet”: Bianca and Cassio’s Relationship in Othello Throughout the critical history of Shakespeare’s Othello, audiences and critics alike have identified love and sexuality as major themes of the play. Indeed, there are many who would argue that the play as a whole is an examination of heterosexual relationships, with all the concerns, such as sexual anxieties, gender inequalities, and emotional struggles that accompany this subject. Discussions of Othello’s portrayal of the relationships between men and women integrate any number of other facets of literary study, such as the psychological factors that shape the relationships of Othello and Desdemona or Iago and Emilia, or the cultural expectations for gender and marriage during the Renaissance, and how these expectations are both upheld and critiqued in Othello, or how the genre elements of sex, or love, tragedies influence the play’s action and the audience’s expectations for the play. Many critics who examine the married relationships focus on the feminine roles that Desdemona and Emilia fill or challenge, while others study the masculine perspectives of these relationships, and seek to explore what prompts Iago’s seeming “hatred of his wife and all women,”1 or Othello’s obsession with Desdemona’s sexuality, and his self-doubts, frequently linked to his age and racial status, about his ability to satisfy her in their relationship. -

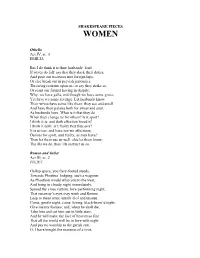

SHAKESPEARE PIECES Othello Act IV, Sc. 3 EMILIA but I Do Think It Is

SHAKESPEARE PIECES WOMEN Othello Act IV, sc. 3 EMILIA But I do think it is their husbands’ fault If wives do fall: say that they slack their duties, And pour our treasures into foreign laps, Or else break out in peevish jealousies, Throwing restraint upon us; or say they strike us, Or scant our former having in despite; Why, we have galls, and though we have some grace, Yet have we some revenge. Let husbands know Their wives have sense like them: they see and smell And have their palates both for sweet and sour, As husbands have. What is it that they do When they change us for others? Is it sport? I think it is: and doth affection breed it? I think it doth: is’t frailty that thus errs? It is so too: and have not we affections, Desires for sport, and frailty, as men have? Then let them use us well: else let them know, The ills we do, their ills instruct us so. Romeo and Juliet Act III, sc. 2 JULIET Gallop apace, you fiery-footed steeds, Towards Phoebus’ lodging: such a wagoner As Phaethon would whip you to the west, And bring in cloudy night immediately. Spread thy close curtain, love-performing night, That runaway’s eyes may wink and Romeo Leap to these arms, untalk’d of and unseen. Come, gentle night, come, loving, black-brow’d night, Give me my Romeo; and, when he shall die, Take him and cut him out in little stars, And he will make the face of heaven so fine That all the world will be in love with night And pay no worship to the garish sun. -

Early Television Shakespeare from the BBC, 1937-39 Wyver, J

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch An Intimate and Intermedial Form: Early Television Shakespeare from the BBC, 1937-39 Wyver, J. This is a preliminary version of a book chapter published in Shakespeare Survey 69: Shakespeare and Rome, Cambridge University Press, pp. 347-360, ISBN 9781107159068 Details of the book are available on the publisher’s website: https://www.cambridge.org/core/what-we-publish/collections/shakespea... The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] 1 An intimate and intermedial form: early television Shakespeare from the BBC, 1937-39 In the twenty-seven months between February 1937 and April 1939 the fledgling BBC television service from Alexandra Palace broadcast more than twenty Shakespeare adaptations.1 The majority of these productions were short programmes featuring ‘scenes from…’ the plays, although there were also substantial adaptations of Othello (1937), Julius Caesar (1938), Twelfth Night and The Tempest (both 1939) as well as a presentation of David Garrick’s 1754 version of The Taming of the Shrew, Katharine and Petruchio (1939). There were other Shakespeare-related programmes as well, and the playwright himself appeared in three distinct historical dramas. In large part because no recordings exist of these transmissions (or of any British television Shakespeare before 1955), these ‘lost’ adaptations have received little scholarly attention. -

Shakespeare's Othello Beyond the Boundaries of the Page

http://dx.doi.org/10.5007/2175-7917.2015v20n2p11 SHAKESPEARE’S OTHELLO BEYOND THE BOUNDARIES OF THE PAGE: AN ANALYSIS OF TWO FILMIC PRODUCTIONS Camila Paula Camilotti* Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Abstract: This article aims at observing and analyzing two filmic productions ofWilliam Shakespeare’s Othello. The first, entitled Othello, was directed, produced and starred by Orson Welles in 1952 andthe second, also entitled Othello, was directed by Oliver Parker in 1995. My main interest in studying these two filmic productions is to observe – based on the notions of theatrical adaptation by Jay Halio (2000), Patrice Pavis (1992), and Allan Dessen (2002) – how each director constructed the seduction moment that happens in Scene III, Act III of Shakespeare’s playtext in their filmic productions. The analysis proves that two different conceptions, separated in time and space, are capable of making Shakespeare’s timelessness transcend and make the modern spectators aware of the fact that the human artistic capacity is able to cross unimaginable limits of creativity and transform a great literary work of art in a great (filmic or theatrical) spectacle. Keywords: Shakespeare’s Othello. Welles’ Othello. Parker’s Othello. Conception. I have’t. It is engendered. Hell and night Must bring this monstrous birth to the world’s light. (II.I 403-404) Whenever a text (in this case, a Shakespearian playtext) crosses the boundaries of the page to live in a theatrical or cinematic medium, with all its visual (and sonorous) elements,it has inevitably to go through several alterations in order to be seen and heard by an audience, in a certain time and space. -

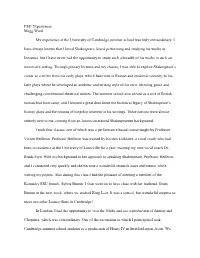

ESU Experiences Megg Ward My Experience at the University Of

ESU Experiences Megg Ward My experience at the University of Cambridge summer school was truly extraordinary. I have always known that I loved Shakespeare, loved performing and studying his works as literature, but I have never had the opportunity to study such a breadth of his works in such an immersive setting. Through plenary lectures and my classes, I was able to explore Shakespeare’s career as a writer from his early plays, which had roots in Roman and medieval comedy, to his later plays where he developed an aesthetic and writing style of his own, blending genre and challenging conventional theatrical unities. The summer school also served as a sort of British monarchial boot camp, and I learned a great deal about the historical legacy of Shakespeare’s history plays and the notions of kingship inherent in his writings. These notions were almost entirely new to me, coming from an American-trained Shakespearean background. I took four classes, one of which was a performance based course taught by Professor Vivien Heilbron. Professor Heilbron was trained by Kristen Linklater, a vocal coach who had been in residence at the University of Louisville for a year, training my own vocal coach Dr. Rinda Frye. With my background in her approach to speaking Shakespeare, Professor Heilbron and I connected very quickly and she became a wonderful research asset and mentor while writing my papers. Also during this class I had the pleasure of meeting a member of the Kentucky ESU branch, Sylvia Bruton. I then went on to have class with her husband, Grant Bruton in the next week, where we studied King Lear. -

SHAKESPEARE in PERFORMANCE Some Screen Productions

SHAKESPEARE IN PERFORMANCE some screen productions PLAY date production DIRECTOR CAST company As You 2006 BBC Films / Kenneth Branagh Rosalind: Bryce Dallas Howard Like It HBO Films Celia: Romola Gerai Orlando: David Oyelewo Jaques: Kevin Kline Hamlet 1948 Two Cities Laurence Olivier Hamlet: Laurence Olivier 1980 BBC TVI Rodney Bennett Hamlet: Derek Jacobi Time-Life 1991 Warner Franco ~effirelli Hamlet: Mel Gibson 1997 Renaissance Kenneth Branagh Hamlet: Kenneth Branagh 2000 Miramax Michael Almereyda Hamlet: Ethan Hawke 1965 Alpine Films, Orson Welles Falstaff: Orson Welles Intemacional Henry IV: John Gielgud Chimes at Films Hal: Keith Baxter Midni~ht Doll Tearsheet: Jeanne Moreau Henry V 1944 Two Cities Laurence Olivier Henry: Laurence Olivier Chorus: Leslie Banks 1989 Renaissance Kenneth Branagh Henry: Kenneth Branagh Films Chorus: Derek Jacobi Julius 1953 MGM Joseph L Caesar: Louis Calhern Caesar Manluewicz Brutus: James Mason Antony: Marlon Brando ~assiis:John Gielgud 1978 BBC TV I Herbert Wise Caesar: Charles Gray Time-Life Brutus: kchard ~asco Antony: Keith Michell Cassius: David Collings King Lear 1971 Filmways I Peter Brook Lear: Paul Scofield AtheneILatenla Love's 2000 Miramax Kenneth Branagh Berowne: Kenneth Branagh Labour's and others Lost Macbeth 1948 Republic Orson Welles Macbeth: Orson Welles Lady Macbeth: Jeanette Nolan 1971 Playboy / Roman Polanslu Macbe th: Jon Finch Columbia Lady Macbeth: Francesca Annis 1998 Granada TV 1 Michael Bogdanov Macbeth: Sean Pertwee Channel 4 TV Lady Macbeth: Greta Scacchi 2000 RSC/ Gregory -

Emilia's Rhetoric of Self-Resistance in Othello

“I nothing know”: Emilia’s Rhetoric of Self-Resistance in Othello Notes 177 SEDERI XIV 178 “I nothing know”: Emilia’s Rhetoric of Self-Resistance in Othello “I nothing know”: Emilia’s Rhetoric of Self-Resistance in Othello Eileen ABRAHAMS University of Texas at Austin ABSTRACT There can be little doubt that by filching Desdemona’s handkerchief Emilia catalyzes her husband’s actions against Othello. To be sure, the handkerchief supplies Iago with the ocular proof he needs to convince the Moor of Desdemona’s infidelity. However, there remains the question of how much, if any, moral responsibility is to be attributed to Emilia for her complicity in Iago’s plot. Critics concur that the question of why Emilia both lies directly to Desdemona and then neglects to speak up even when Othello angrily confronts his wife about the whereabouts of the handkerchief is a deeply problematic one. However, even a cursory glance at the literature points to a critical divide about the answer to this question. Although I agree with Carole Thomas Neely that Emilia is prey to the dominant ideology of wifely virtue, I do not believe that it is either her conception of duty or her desire to act in accord with this ideology that compels her to lie. As the willow scene makes clear, Emilia recognizes the degree to which women’s pre-ordained social roles both consign them to suffer and restrict their freedom to act, and to a certain extent, she accepts her social role. But she does not identify with it, that is, she does not buy into it, and for the right price, she would defy it. -

Examine the Way in Which Female Characters Are Portrayed in the Patriarchal World of Othello

Examine the way in which female characters are portrayed in the patriarchal world of Othello. In the patriarchal world of Othello, set in the late 16th century, the audience may expect submissive, docile female characters that serve as a mere backdrop to the bountiful action of the play. Indeed, the two most prominent male characters, Othello and Iago, both regard women as lesser beings, and do not place much worth or importance on their opinions and ideas, acting in accordance with being products of a patriarchal society. However, the female characters of Shakespeare’s Othello exemplify many traits that modern day women can identify with, and they tend to break the stereotypical perceptions of females of their time. Whether it is by transcending societal expectations in her marriage to a black man and the defiance of her father as with the character of Desdemona, within Bianca’s assertive attitude towards dealing with her object of affection and fixation, or expressing her progressive views on the nature of men as Emilia does, it is evident that women have a large role to play in shaping the text as we know it. Their individual contributions to the resulting tragic ending are extensive, as they are all portrayed as multifaceted, dynamic personalities and exhibit many unique character traits and qualities that resonate with the audience even today. Shakespeare portrays the character of Desdemona through a number of prominent character traits that define her throughout the play, especially within her strength of character, her dutiful and loyal nature, and her naivety. The beginning of the play reveals her secret marriage to Othello, a black man, in the first scene itself, and this indicates to the audience that she is breaking social barriers for the sake of her own happiness and the affection she cherishes for Othello. -

“I Must Be Circumstanced:” Bianca's Effect on Othello

“I Must Be Circumstanced:” Bianca’s Effect on Othello The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Bastin, Jennifer. 2017. “I Must Be Circumstanced:” Bianca’s Effect on Othello. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33826658 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA “I Must Be Circumstanced:” Bianca’s Effect on Othello Jennifer Bastin A Thesis in the Field of English Literature for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University May 2017 Abstract This study examines the inclusion of Bianca in William Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of Othello, Moor of Venice. What purpose did the character serve, if any? How does the play benefit from her creation? Previous scholarly criticism, along with a close textual analysis of both the play and its source material, provide a deeper understanding of the character. The investigation concludes that Bianca helps the audience decipher the play’s action by creating a triptych of romantic couples, providing a better picture of the main character by serving as his foil, and by providing catharsis for the audience, cementing the interpretation of the drama as tragedy. Author Biography Jennifer Bastin saw an uncut, repertory production of Hamlet at eight years old and has been in love with Shakespeare ever since. -

CHAN 3068 BOOK COVER.Qxd 16/7/07 10:47 Am Page 1

CHAN 3068 BOOK COVER.qxd 16/7/07 10:47 am Page 1 CHAN 3068(2) CHANDOS O PERA IN ENGLISH PETE MOOES FOUNDATION CHAN 3068 BOOK.qxd 16/7/07 10:52 am Page 2 Giuseppe Verdi (1813–1901) Otello Dramma lirico in four acts Lebrecht Collection Lebrecht Libretto by Arrigo Boito after Shakespeare, English translation by Andrew Porter Otello, a Moor, general of the Venetian army ................................................ Charles Craig tenor Desdemona, Otello’s wife ....................................................................Rosalind Plowright soprano Iago, an ensign ............................................................................................Neil Howlett baritone Emilia, Iago’s wife............................................................................Shelagh Squires mezzo-soprano Cassio, a platoon leader........................................................................Bonaventura Bottone tenor Roderigo, a Venetian gentleman ..........................................................................Stuart Kale tenor Lodovico, an ambassador of the Venetian Republic ..................................................Sean Rea bass Montano, Otello’s predecessor as Governor of Cyprus ............................Malcolm Rivers baritone Herald ....................................................................................................Gordon Traynor baritone English National Opera Orchestra and Chorus Mark Elder Giuseppe Verdi 3 CHAN 3068 BOOK.qxd 16/7/07 10:52 am Page 4 COMPACT DISC ONE Time Page Time Page Act I Act II Scene 1 Scene 1 1 ‘See, the sail there!’ 4:22 [p. 84] 11 ‘Don’t give up hope, but trust in me’ 2:42 [p. 93] Chorus, Montano, Cassio, Iago, Roderigo Iago, Cassio 2 ‘Oh rejoice now!’ 2:17 [p. 85] Otello, Chorus Scene 2 3 ‘Roderigo, speak up’ 2:45 [p. 86] 12 ‘Take it; take the path to your ruin’ 0:32 [p. 94] Iago, Roderigo 13 ‘Yes, I believe in a God who has created me’ 4:25 [p. 94] 4 ‘Flame of rejoicing!’ 2:23 [p. 87] 14 ‘There she is… Cassio… your chance…’ 1:23 [p.