Act 4 Othello Scene 1 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Otello Program

GIUSEPPE VERDI otello conductor Opera in four acts Gustavo Dudamel Libretto by Arrigo Boito, based on production Bartlett Sher the play by William Shakespeare set designer Thursday, January 10, 2019 Es Devlin 7:30–10:30 PM costume designer Catherine Zuber Last time this season lighting designer Donald Holder projection designer Luke Halls The production of Otello was made possible by revival stage director Gina Lapinski a generous gift from Jacqueline Desmarais, in memory of Paul G. Desmarais Sr. The revival of this production is made possible by a gift from Rolex general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2018–19 SEASON The 345th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIUSEPPE VERDI’S otello conductor Gustavo Dudamel in order of vocal appearance montano a her ald Jeff Mattsey Kidon Choi** cassio lodovico Alexey Dolgov James Morris iago Željko Lučić roderigo Chad Shelton otello Stuart Skelton desdemona Sonya Yoncheva This performance is being broadcast live on Metropolitan emilia Opera Radio on Jennifer Johnson Cano* SiriusXM channel 75 and streamed at metopera.org. Thursday, January 10, 2019, 7:30–10:30PM KEN HOWARD / MET OPERA Stuart Skelton in Chorus Master Donald Palumbo the title role and Fight Director B. H. Barry Sonya Yoncheva Musical Preparation Dennis Giauque, Howard Watkins*, as Desdemona in Verdi’s Otello J. David Jackson, and Carol Isaac Assistant Stage Directors Shawna Lucey and Paula Williams Stage Band Conductor Gregory Buchalter Prompter Carol Isaac Italian Coach Hemdi Kfir Met Titles Sonya Friedman Children’s Chorus Director Anthony Piccolo Assistant Scenic Designer, Properties Scott Laule Assistant Costume Designers Ryan Park and Wilberth Gonzalez Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted in Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes executed by Metropolitan Opera Costume Department; Angels the Costumiers, London; Das Gewand GmbH, Düsseldorf; and Seams Unlimited, Racine, Wisconsin Wigs and Makeup executed by Metropolitan Opera Wig and Makeup Department This production uses strobe effects. -

Verdi Otello

VERDI OTELLO RICCARDO MUTI CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ALEKSANDRS ANTONENKO KRASSIMIRA STOYANOVA CARLO GUELFI CHICAGO SYMPHONY CHORUS / DUAIN WOLFE Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) OTELLO CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA RICCARDO MUTI 3 verdi OTELLO Riccardo Muti, conductor Chicago Symphony Orchestra Otello (1887) Opera in four acts Music BY Giuseppe Verdi LIBretto Based on Shakespeare’S tragedy Othello, BY Arrigo Boito Othello, a Moor, general of the Venetian forces .........................Aleksandrs Antonenko Tenor Iago, his ensign .........................................................................Carlo Guelfi Baritone Cassio, a captain .......................................................................Juan Francisco Gatell Tenor Roderigo, a Venetian gentleman ................................................Michael Spyres Tenor Lodovico, ambassador of the Venetian Republic .......................Eric Owens Bass-baritone Montano, Otello’s predecessor as governor of Cyprus ..............Paolo Battaglia Bass A Herald ....................................................................................David Govertsen Bass Desdemona, wife of Otello ........................................................Krassimira Stoyanova Soprano Emilia, wife of Iago ....................................................................BarBara DI Castri Mezzo-soprano Soldiers and sailors of the Venetian Republic; Venetian ladies and gentlemen; Cypriot men, women, and children; men of the Greek, Dalmatian, and Albanian armies; an innkeeper and his four servers; -

The Unconsummated Marriage in “Othello”

Goodfellow 1 K. A. Goodfellow Professor Henderson English 102 5 May 200X A Guiltless Death: The Unconsummated Marriage in Othello Although Desdemona and Othello are truly in love when they marry, they are unable to consummate their marriage in William Shakespeare's Othello. Because their marriage was tragically short (only three days), there were few opportunities for them to be together alone. When the opportunity did present itself, unforeseen circumstances arose and the moment was lost. This being the case, in murdering Desdemona, Othello kills a virginal wife -- a deeper irony considering that he murders her because he believes her to be unchaste. Desdemona is faithful before and during her marriage to Othello. Her own words defend the fact that she is an "honest" wife. After Othello accuses her for the first time of being a whore, Desdemona responds to Iago's queries of why Othello would thus accuse her with "I do not know. I am sure I am none such" (4.2.130). She continues to defend her virtue up to the moment of her death when she says "A guiltless death I die" (5.2.126). While Desdemona's words alone may not be enough proof of her faithfulness to Othello, her attendant, Emilia, also denies Othello's accusations of Desdemona. When Othello's questions Emilia about Desdemona's honesty, she replies "For if she be not honest, chaste, and true,/There's no man happy; the purest of their wives/ Is foul as slander" (4.2.18-20). As Desdemona's longtime servant, she is more aware than anyone Copyright (c) 2005, Pearson Education Inc., publishing as Pearson Longman. -

Jealousy and Destruction in William Shakespeare's

Crossing the Border: International Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies Volume 4; Number 1; 15 April 2016 ISSN 2350-8752 (Print); ISSN 2350-8922 (Online) JEALOUSY AND DESTRUCTION IN WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE’S OTHELLO Ram Prasad Rai (Nepal) ABSTRACT Othello is honest. He wants to establish an order and peace in the society. He falls in love with a white lady, Desdemona. Despite the discontentment of Desdemona’s father Brobantio, they marry each other. Iago, an evil-minded man, is not happy with the promotion of Cassio, a junior o! cer to Iago, to lieutenant’s post in support of the chief Othello. Iago becomes jealous to Cassio and plans to destroy the relation between Othello and Cassio in any way it is pos- sible. He uses Roderigo, a rejected suitor to Desdemona and Emilia, the innocent wife of Iago in his evil plot. Iago treacherously makes Desdemona’s handkerchief, a marriage gi" from Othello, reach in Cassio through Emilia. # en he notices Othello about the Apresence of the handkerchief in Cassio as an accusation of Desdemona’s falling in love with Cassio. In reality, both Cassio and Desdemona are innocent. # ey are honest and loyal to their moral position. But because of jealousy grown in Othello by Iago, Othello plans to murder his kind and truly loving wife and his dutiful junior o! cer Cassio. Othello kills Desdemona and Iago kills his wife Emilia as she discloses the reality about Iago’s evilness. Othello kills himself a" er he knows about Iago’s treachery. As a result, all the happiness, peace and love in the families of Othello and Iago get spoilt completely because of just jealousy upon each other. -

Othello, a Tragedy Act 1: Palace

Othello, A Tragedy Act 1: Palace Set - The Duke's Court Iago and Roderigo have started a rumor that Othello won over Desdemona through witchcraft. Before the Duke of Venice, Othello explains that he won Desdemona through his stories of adventure and war. Desdemona confirms this, and insists that she loves Othello. Act 2: Street Set - A Drunkard's Bar Iago gets Cassio drunk and convinces him to start a fight with a rival officer, Roderigo. Cassio accidentally wounds the Governor, and Othello is summoned. Iago tells Othello that it was Cassio that started the fight, and Othello strips Cassio of his title. Iago then tells Cassio that he should attempt to win over Othello through Desdemona. Act 3: Palace Set - Royal Chambers Cassio appeals to Desdemona to help him earn Othello's forgiveness. He leaves before Othello returns, however, and Iago uses this to convince Othello that Desdemona has betrayed him with Cassio. Desedemona makes things worse by attempting to convince Othello to forgive Cassio. Iago steals Desdemona's handkerchief and plants it on Cassio. Act 4: Palace Set - Private Chambers Othello growing suspicious of Desdemona, asks Iago for evidence. Iago suggests that he has seen Cassio with Desdemona's handkerchief. Othello asks Desdemona for her handkerchief, which she confesses that she has lost, and attempts to change the subject by pleading Cassio's case. Act 5: Palace Set - Private Chambers Othello confronts Desdemona, but does not believe her story. He kills her. After her death, he realizes what has happened and confronts Iago. They duel and both are wounded. -

Bianca and Cassio's Relationship in <Em>Othello</Em>

Marquette University From the SelectedWorks of Sarah E. Thompson 2012 "I Am No Strumpet": Bianca and Cassio's Relationship in <em>Othello</em> Sarah E. Thompson, Marquette University Available at: https://works.bepress.com/sarah_thompson/1/ 1 Sarah Thompson English 6220 December 12, 2012 “I Am No Strumpet”: Bianca and Cassio’s Relationship in Othello Throughout the critical history of Shakespeare’s Othello, audiences and critics alike have identified love and sexuality as major themes of the play. Indeed, there are many who would argue that the play as a whole is an examination of heterosexual relationships, with all the concerns, such as sexual anxieties, gender inequalities, and emotional struggles that accompany this subject. Discussions of Othello’s portrayal of the relationships between men and women integrate any number of other facets of literary study, such as the psychological factors that shape the relationships of Othello and Desdemona or Iago and Emilia, or the cultural expectations for gender and marriage during the Renaissance, and how these expectations are both upheld and critiqued in Othello, or how the genre elements of sex, or love, tragedies influence the play’s action and the audience’s expectations for the play. Many critics who examine the married relationships focus on the feminine roles that Desdemona and Emilia fill or challenge, while others study the masculine perspectives of these relationships, and seek to explore what prompts Iago’s seeming “hatred of his wife and all women,”1 or Othello’s obsession with Desdemona’s sexuality, and his self-doubts, frequently linked to his age and racial status, about his ability to satisfy her in their relationship. -

The Inevitable Death of Desdemona: Shakespeare and the Mediterranean Tradition

THE INEVITABLE DEATH OF DESDEMONA: SHAKESPEARE AND THE MEDITERRANEAN TRADITION María Luisa Dañobeitia University of Granada Our endeavour in this paper is none other than examining the literary impact of an archaic preoccupation, honour and reputation. This preoccupation is almost omnipresent in many cultures but not every culture solves issues involving the injured honour of an individual, or that of family, or a clan, in an identical manner. Consequently it has been a motif that has given an ample number of writes the chance of creating stories with a single thematic nucleus: honour. There are many elements that could affect both honour and reputation, but in this paper we are concerned only with one specific type of honour: that which embraces the behaviour of a woman. This type of honour involves both a woman and man simply because the honour and good name of a man depends on the demeanour of his wife, or his mother, or even his own sister. To be a man whose honour has been stained by the sexual behaviour of a woman who is either related to him by blood ties, or by the bond of matrimony, is not a trivial matter. Society, not the law, does censure and ridicules him. So, for a man this type of aggression becomes an intolerable affront he must revenge if he wants to regain the respect of his society. The way in which a given community, or culture, regards this class of offense coerces the man to become the custodian of the honour of his family. Obviously to be this kind of keeper is difficult for it involves a great deal of voyeurism, since he must observe not only the sexual behaviour of his wife, is he has one, but that of the ladies of his family. -

SHAKESPEARE PIECES Othello Act IV, Sc. 3 EMILIA but I Do Think It Is

SHAKESPEARE PIECES WOMEN Othello Act IV, sc. 3 EMILIA But I do think it is their husbands’ fault If wives do fall: say that they slack their duties, And pour our treasures into foreign laps, Or else break out in peevish jealousies, Throwing restraint upon us; or say they strike us, Or scant our former having in despite; Why, we have galls, and though we have some grace, Yet have we some revenge. Let husbands know Their wives have sense like them: they see and smell And have their palates both for sweet and sour, As husbands have. What is it that they do When they change us for others? Is it sport? I think it is: and doth affection breed it? I think it doth: is’t frailty that thus errs? It is so too: and have not we affections, Desires for sport, and frailty, as men have? Then let them use us well: else let them know, The ills we do, their ills instruct us so. Romeo and Juliet Act III, sc. 2 JULIET Gallop apace, you fiery-footed steeds, Towards Phoebus’ lodging: such a wagoner As Phaethon would whip you to the west, And bring in cloudy night immediately. Spread thy close curtain, love-performing night, That runaway’s eyes may wink and Romeo Leap to these arms, untalk’d of and unseen. Come, gentle night, come, loving, black-brow’d night, Give me my Romeo; and, when he shall die, Take him and cut him out in little stars, And he will make the face of heaven so fine That all the world will be in love with night And pay no worship to the garish sun. -

Early Television Shakespeare from the BBC, 1937-39 Wyver, J

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch An Intimate and Intermedial Form: Early Television Shakespeare from the BBC, 1937-39 Wyver, J. This is a preliminary version of a book chapter published in Shakespeare Survey 69: Shakespeare and Rome, Cambridge University Press, pp. 347-360, ISBN 9781107159068 Details of the book are available on the publisher’s website: https://www.cambridge.org/core/what-we-publish/collections/shakespea... The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] 1 An intimate and intermedial form: early television Shakespeare from the BBC, 1937-39 In the twenty-seven months between February 1937 and April 1939 the fledgling BBC television service from Alexandra Palace broadcast more than twenty Shakespeare adaptations.1 The majority of these productions were short programmes featuring ‘scenes from…’ the plays, although there were also substantial adaptations of Othello (1937), Julius Caesar (1938), Twelfth Night and The Tempest (both 1939) as well as a presentation of David Garrick’s 1754 version of The Taming of the Shrew, Katharine and Petruchio (1939). There were other Shakespeare-related programmes as well, and the playwright himself appeared in three distinct historical dramas. In large part because no recordings exist of these transmissions (or of any British television Shakespeare before 1955), these ‘lost’ adaptations have received little scholarly attention. -

Shakespeare's Othello Beyond the Boundaries of the Page

http://dx.doi.org/10.5007/2175-7917.2015v20n2p11 SHAKESPEARE’S OTHELLO BEYOND THE BOUNDARIES OF THE PAGE: AN ANALYSIS OF TWO FILMIC PRODUCTIONS Camila Paula Camilotti* Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Abstract: This article aims at observing and analyzing two filmic productions ofWilliam Shakespeare’s Othello. The first, entitled Othello, was directed, produced and starred by Orson Welles in 1952 andthe second, also entitled Othello, was directed by Oliver Parker in 1995. My main interest in studying these two filmic productions is to observe – based on the notions of theatrical adaptation by Jay Halio (2000), Patrice Pavis (1992), and Allan Dessen (2002) – how each director constructed the seduction moment that happens in Scene III, Act III of Shakespeare’s playtext in their filmic productions. The analysis proves that two different conceptions, separated in time and space, are capable of making Shakespeare’s timelessness transcend and make the modern spectators aware of the fact that the human artistic capacity is able to cross unimaginable limits of creativity and transform a great literary work of art in a great (filmic or theatrical) spectacle. Keywords: Shakespeare’s Othello. Welles’ Othello. Parker’s Othello. Conception. I have’t. It is engendered. Hell and night Must bring this monstrous birth to the world’s light. (II.I 403-404) Whenever a text (in this case, a Shakespearian playtext) crosses the boundaries of the page to live in a theatrical or cinematic medium, with all its visual (and sonorous) elements,it has inevitably to go through several alterations in order to be seen and heard by an audience, in a certain time and space. -

ESU Experiences Megg Ward My Experience at the University Of

ESU Experiences Megg Ward My experience at the University of Cambridge summer school was truly extraordinary. I have always known that I loved Shakespeare, loved performing and studying his works as literature, but I have never had the opportunity to study such a breadth of his works in such an immersive setting. Through plenary lectures and my classes, I was able to explore Shakespeare’s career as a writer from his early plays, which had roots in Roman and medieval comedy, to his later plays where he developed an aesthetic and writing style of his own, blending genre and challenging conventional theatrical unities. The summer school also served as a sort of British monarchial boot camp, and I learned a great deal about the historical legacy of Shakespeare’s history plays and the notions of kingship inherent in his writings. These notions were almost entirely new to me, coming from an American-trained Shakespearean background. I took four classes, one of which was a performance based course taught by Professor Vivien Heilbron. Professor Heilbron was trained by Kristen Linklater, a vocal coach who had been in residence at the University of Louisville for a year, training my own vocal coach Dr. Rinda Frye. With my background in her approach to speaking Shakespeare, Professor Heilbron and I connected very quickly and she became a wonderful research asset and mentor while writing my papers. Also during this class I had the pleasure of meeting a member of the Kentucky ESU branch, Sylvia Bruton. I then went on to have class with her husband, Grant Bruton in the next week, where we studied King Lear. -

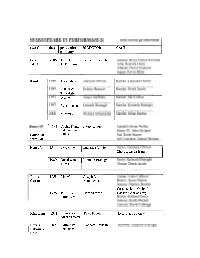

SHAKESPEARE in PERFORMANCE Some Screen Productions

SHAKESPEARE IN PERFORMANCE some screen productions PLAY date production DIRECTOR CAST company As You 2006 BBC Films / Kenneth Branagh Rosalind: Bryce Dallas Howard Like It HBO Films Celia: Romola Gerai Orlando: David Oyelewo Jaques: Kevin Kline Hamlet 1948 Two Cities Laurence Olivier Hamlet: Laurence Olivier 1980 BBC TVI Rodney Bennett Hamlet: Derek Jacobi Time-Life 1991 Warner Franco ~effirelli Hamlet: Mel Gibson 1997 Renaissance Kenneth Branagh Hamlet: Kenneth Branagh 2000 Miramax Michael Almereyda Hamlet: Ethan Hawke 1965 Alpine Films, Orson Welles Falstaff: Orson Welles Intemacional Henry IV: John Gielgud Chimes at Films Hal: Keith Baxter Midni~ht Doll Tearsheet: Jeanne Moreau Henry V 1944 Two Cities Laurence Olivier Henry: Laurence Olivier Chorus: Leslie Banks 1989 Renaissance Kenneth Branagh Henry: Kenneth Branagh Films Chorus: Derek Jacobi Julius 1953 MGM Joseph L Caesar: Louis Calhern Caesar Manluewicz Brutus: James Mason Antony: Marlon Brando ~assiis:John Gielgud 1978 BBC TV I Herbert Wise Caesar: Charles Gray Time-Life Brutus: kchard ~asco Antony: Keith Michell Cassius: David Collings King Lear 1971 Filmways I Peter Brook Lear: Paul Scofield AtheneILatenla Love's 2000 Miramax Kenneth Branagh Berowne: Kenneth Branagh Labour's and others Lost Macbeth 1948 Republic Orson Welles Macbeth: Orson Welles Lady Macbeth: Jeanette Nolan 1971 Playboy / Roman Polanslu Macbe th: Jon Finch Columbia Lady Macbeth: Francesca Annis 1998 Granada TV 1 Michael Bogdanov Macbeth: Sean Pertwee Channel 4 TV Lady Macbeth: Greta Scacchi 2000 RSC/ Gregory