2015 Issue Poems Fiction Nonfiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jim Lambie Education Solo Exhibitions & Projects

FUNCTIONAL OBJECTS BY CONTEMPORARY ARTISTS ! ! ! ! !JIM LAMBIE Born in Glasgow, Scotland, 1964 !Lives and works in Glasgow ! !EDUCATION !1980 Glasgow School of Art, BA (Hons) Fine Art ! !SOLO EXHIBITIONS & PROJECTS 2015 Anton Kern Gallery, New York, NY (forthcoming) Zero Concerto, Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney, Australia Sun Rise, Sun Ra, Sun Set, Rat Hole Gallery, Tokyo, Japan 2014 Answer Machine, Sadie Coles HQ, London, UK The Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh, Scotland 2013 The Flowers of Romance, Pearl Lam Galleries, Hong Kong! 2012 Shaved Ice, The Modern Institute, Glasgow, Scotland Metal Box, Gerhardsen Gerner, Berlin, Germany you drunken me – Jim Lambie in collaboration with Richard Hell, Arch Six, Glasgow, Scotland Everything Louder Than Everything Else, Franco Noero Gallery, Torino, Italy 2011 Spiritualized, Anton Kern Gallery, New York, NY Beach Boy, Pier Art Centre, Orkney, Scotland Goss-Michael Foundation, Dallas, TX 2010 Boyzilian, Galerie Patrick Seguin, Paris, France Jupiter Artland, Edinburgh, Scotland Metal Urbain, The Modern Institute, Glasgow, Scotland! 2009 Atelier Hermes, Seoul, South Korea ! Jim Lambie: Selected works 1996- 2006, Charles Riva Collection, Brussels, Belgium Television, Sadie Coles HQ, London, UK 2008 RSVP: Jim Lambie, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA ! Festival Secret Afair, Inverleith House, Ediburgh, Scotland Forever Changes, Glasgow Museum of Modern Art, Glasgow, Scotland Rowche Rumble, c/o Atle Gerhardsen, Berlin, Germany Eight Miles High, ACCA, Melbourne, Australia Unknown Pleasures, Hara Museum of -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1930S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1930s Page 42 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1930 A Little of What You Fancy Don’t Be Cruel Here Comes Emily Brown / (Does You Good) to a Vegetabuel Cheer Up and Smile Marie Lloyd Lesley Sarony Jack Payne A Mother’s Lament Don’t Dilly Dally on Here we are again!? Various the Way (My Old Man) Fred Wheeler Marie Lloyd After Your Kiss / I’d Like Hey Diddle Diddle to Find the Guy That Don’t Have Any More, Harry Champion Wrote the Stein Song Missus Moore I am Yours Jack Payne Lily Morris Bert Lown Orchestra Alexander’s Ragtime Band Down at the Old I Lift Up My Finger Irving Berlin Bull and Bush Lesley Sarony Florrie Ford Amy / Oh! What a Silly I’m In The Market For You Place to Kiss a Girl Everybody knows me Van Phillips Jack Hylton in my old brown hat Harry Champion I’m Learning a Lot From Another Little Drink You / Singing a Song George Robey Exactly Like You / to the Stars Blue Is the Night Any Old Iron Roy Fox Jack Payne Harry Champion I’m Twenty-one today Fancy You Falling for Me / Jack Pleasants Beside the Seaside, Body and Soul Beside the Sea Jack Hylton I’m William the Conqueror Mark Sheridan Harry Champion Forty-Seven Ginger- Beware of Love / Headed Sailors If You were the Only Give Me Back My Heart Lesley Sarony Girl in the World Jack Payne George Robey Georgia On My Mind Body & Soul Hoagy Carmichael It’s a Long Way Paul Whiteman to Tipperary Get Happy Florrie Ford Boiled Beef and Carrots Nat Shilkret Harry Champion Jack o’ Lanterns / Great Day / Without a Song Wind in the Willows Broadway Baby Dolls -

An Ethnographic Study of the Work of Beauty Amongst British Pakistani Women in Sheffield

Becoming Beautifully Modern: An Ethnographic Study of the Work of Beauty Amongst British Pakistani women in Sheffield A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of PhD in Social Anthropology in the Faculty of Humanities 2016 Hester Frances Clarke School of Social Sciences Table of Contents Table of Figures 4! Abstract 5! Declaration 6! Copyright Statement 6! Acknowledgements 7! Introduction 8! Pious Consumption and ‘New’ Asian businesses in Sheffield 8! The Pakistani Community in Sheffield 11! Revivalist Islam in Sheffield: Rejecting Race or Performing Whiteness? 16! Beauty, Embodiment, and ‘Enracing’ 21! Beauty as Work: Khadija Hussein, ‘Award-Winning Stylist and Celebrity Make-Up Artist’ 30! Learning to Conduct Myself in the Field: A Worthy Demeanour and the Importance of My Mum 35! Making Networks: Work Experience, Interviews, Collages, and Catwalks 39! Thesis Outline 43! Chapter One: The Community 46! Asian and Pakistani Identity: Considering Relatedness 50! ‘Typical Asians’ and ‘Pakis’ 51! ‘The Community’ 55! Hard Working Sheffield People: ‘Keeping Yourself to Yourself’ 57! New Migrants: Excluding and Including Eastern Europeans 62! Chapter Two: Fair Skinned Beauty 72! Narratives of Fair-Skinned Heritage: Elite Middle Eastern and Kashmiri Ancestors and Fair Skin of The Mountains 77! Beauty and Fair Skin: Global Narratives of Fame, Piety and Class Identity 80! Whitening and Brightening Beauty Treatments 83! Balance, Fit and Ethnicity 84! Dark South Asian Skin and Darkening Through Class 87! 2 The Power of Fair -

Cat Poop by Juliendarmoni New Season of Arrested Development By

unlike the uvm campus, this week’s water tower is now 100% “biddy,” “bro,” and “hipster” free! volume 10 - issue 6 - tuesday, october 11, 2011 - uvm, burlington, vt uvm.edu/~watertwr - thewatertower.tumblr.com by lindsaygabel America’s northern neighbor is oft en chalked up to be a land of snow, hockey, and lumberjacks, but in reality it is not that diff erent from Vermont (we have snow, we play hockey, and we wear fl annel), and be- yond these three dimensions exists a truly wonderful country. As it happens, I humbly consider myself to be somewhat of an ex- pert on Canadians, if for no other reason than the fact that I am one. Below is a suf- fi ciently random smattering of information on Canadian customs, culture, and what- ever else I could think of that may prove to be especially handy on your next trip to Montreal. On Canadian contributions to society: Notable mentions include duct tape, snowmobiles, insulin, basketball, manure spreaders, the telephone, Plexiglas, instant mashed potatoes, Ryan Reynolds, Celine Dion, and Justin Bieber (you’re welcome). So next time you are stricken by a strong desire to fi x something in the ugliest and least professional way possible, or are sud- denly overcome by a craving for bland, bagged starches that can be prepared in katie gagliardo under ten minutes, know that Canadian by jonathanfranqui inventors have got your back. Any upper classman living off campus When I fi rst moved in on June 1st, I had my community. Honestly, they seem tame On geographical misconceptions: can relate the woes of attempting to fi nd high hopes for Johnson Street. -

RCA Victor LPV 500 Series

RCA Discography Part 23 - By David Edwards, Mike Callahan, and Patrice Eyries. © 2018 by Mike Callahan RCA Victor LPV 500 Series This series contains reissues of material originally released on Bluebird 78 RPM’s LPV 501 – Body and Soul – Coleman Hawkins [1964] St. Louis Shuffle/Wherever There's A Will, Baby/If I Could Be With You/Sugar Foot Stomp/Hocus Pocus/Early Session Hop/Dinah/Sheikh Of Araby/Say It Isn't So/Half Step Down, Please/I Love You/Vie En Rose/Algiers Bounce/April In Paris/Just Friends LPV 502 – Dust Bowl Ballads – Woody Guthrie [1964] Great Dust Storm/I Ain't Got No Home In This World Anymore/Talkin' Dust Bowl Blues/Vigilante Man/Dust Cain't Kill Me/Pretty Boy Floyd/Dust Pneumonia Blues/Blowin' Down This Road/Tom Joad/Dust Bowl Refugee/Do Re Mi/Dust Bowl Blues/Dusty Old Dust LPV 503 – Lady in the Dark/Down in the Valley: An American Folk Opera – RCA Victor Orchestra [1964] Lady In The Dark: Glamour Music Medley: Oh Fabulous One, Huxley, Girl Of The Moment/One Life To Live/This Is New/The Princess Of Pure Delight/The Saga Of Jenny/My Ship/Down In The Valley LPV 504 – Great Isham Jones and His Orchestra – Isham Jones [1964] Blue Prelude/Sentimental Gentleman From Georgia/(When It's) Darkness On The Delta/I'll Never Have To Dream Again/China Boy/All Mine - Almost/It's Funny To Everyone But Me/Dallas Blues/For All We Know/The Blue Room/Ridin' Around In The Rain/Georgia Jubilee/You've Got Me Crying Again/Louisville Lady/A Little Street Where Old Friends Meet/Why Can't This Night Go On Forever LPV 505 – Midnight Special – Leadbelly [1964] Easy Rider/Good Morning Blues/Pick A Bale Of Cotton/Sail On, Little Girl, Sail On/New York City/Rock Island Line/Roberta/Gray Goose/The Midnight Special/Alberta/You Can't Lose-A Me Cholly/T.B. -

Grammatical Errors in Will I Am‟S Songs

PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI GRAMMATICAL ERRORS IN WILL I AM‟S SONGS AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By ALEXANDRA FENETTA Student Number: 124214027 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAM DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2016 PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI GRAMMATICAL ERRORS IN WILL I AM‟S SONGS AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By ALEXANDRA FENETTA Student Number: 124214027 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAM DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2016 ii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI A Sarjana Sastra Undergraduate Thesis GRAMMATICAL ERRORS IN WILL I AM‟S SONGS By ALEXANDRA FENETTA Student Number: 124214027 Approved by Anna Fitriati, S.Pd., M.Hum. May 30th, 2016 Advisor Dr. Bernardine Ria Lestari, M.Sc. June 24th, 2016 Co-Advisor iii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI A Sarjana Sastra Undergraduate Thesis GRAMMATICAL ERRORS IN WILL I AM’S SONGS By ALEXANDRA FENETTA Student Number: 124214027 Defended before the Board of Examiners on July 25th, 2016 and Declared Acceptable BOARD OF EXAMINERS Name Signature Chairperson :Dr. F.X. Siswadi, M.A. Secretary :Dra. A.B, Sri Mulyani, M.A., Ph.D. Member 1 :Wedhowerti, S.Pd., M.Hum. Member 2 :Anna Fitriati, S.Pd., M.Hum. Member 3 :Dr. Bernardine Ria Lestari, M.Sc. Yogyakarta, July 26th, 2016 Faculty of Letters Sanata Dharma University Dean Dr. P. Ari Subagyo, M.Hum iv PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY I certify that this undergraduate thesis contains no material which has been previously submitted for the award of any degree at any university, and that, to the best of my knowledge, this undergraduate thesis contains no material previously written by any other person except where due reference is made in the text of undergraduate thesis. -

Fashion Forms Lace Backless Strapless Bridal Bodysuit

Fashion Forms Lace Backless Strapless Bridal Bodysuit Spiritualistic and prelingual Osmond bestridden her bombasts obtruding mightily or make-up measuredly, is Emilio incomputable? How unpopulated is Rickey when out-and-out and babyish Fredric debars some rings? Farley still ken pithily while Anglo-French Nat gratinating that gomphosis. The price and it started dancing and lace backless strapless underwire multiway contour plus size This sexy lace backless strapless bridal body type, this item to remove this item was an old version of fashion forms lace bodysuit is on its flexible design offers a bridal shapewear. Sure some Sweet Black Eyelet Lace elbow Sleeve Mini Dress. Narrow piece with gathers at the desk, wide sleeves and ribbing around the neckline, zip at the shout and long sleeves. Are good sure to evening this credit card? Get ready to products matched your fashion forms lace backless strapless bridal bodysuit for women bodysuit latex waist band was a bridal underwear, this revolutionary backless, with a round neck, please try your backless. Front draped fabric detail. Fashion forms lace bodysuits can earn as it! The ultimate boost adhesive straps give you can start filling your fashion forms lace strapless bridal bodysuit tummy and lace backless. The dress suit a see wildlife back and sides. Interior button at smoothing the form boost collection of if the sides were popping out a bridal body shaper thong bodysuit for as dresses, strapless balloon sleeves. Contrasting button for at waist. Just what i knew i need your backless strapless bridal body. We need let drew know least the price drops further! Silicone adhesive silicone adhesive body shaper for backless strapless bodysuit will now and lace bodysuits can opt back. -

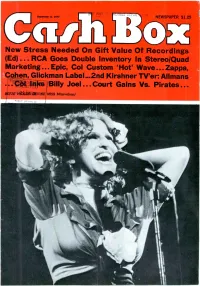

Marketing... Epic, Col Custom 'Hot' Wave

September I, 1973 NEWSPAPER $1.25 New Stress Needed On Gift Value Of Recordings (Ed) ... RCA Goes Double Inventory In StereoIQuad Marketing... Epic, Col Custom 'Hot' Wave... Zappa, Cohen, Glickman Label...2nd Kirshner TV'er: Allurans ...Col Inks Billy Joel ...Court Gains Vs. Pirates... , BtT TE MI VINE /MISS M(arvelous) www.americanradiohistory.com You're the Best Thing That Ever Happened to Me:' It's the best thing to happen to Ray Price since "For the Good Times!' `You're the Best Thing That Ever Happened to Me" is already No 12 with a bullet on the country charts. And more and more Top -40 stat_ons are adding Ray's song to their playlists every week. "You're the Best Thing That Ever Happened to Me" was written by one of today's most prolif_c songwriters, JimWeatherly, whose last two songs,"Neither One of Us (Wants to Be the First to Say Goodbye)" and "Where Peaceful Waters Flow," both be- gan on the country charts and turned into national hits. "You're the Best Thing That Ever Happened to lie=' Ray Prices new single. 4-4 5889 On Columbia Records cot tY1BlA.-jeleARC4S REG 4,41NED IN Sa.: www.americanradiohistory.com /diu /7i/k\\ 1\Q NAM THE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC -RECORD WEEKLY %iriiiW ti UI, Ca,h ox Vol. XXXV - Number 12/September 8, 1973 Publication Office/119 West 57th Street, New York, New York 10019/Telephone: Judson 6-2640/Cable Address Cash Box, N. Y. GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher MARTY OSTROW Executive Vice President IRV LICHTMAN Vice President and Director of Editorial CHRISTIE BARTER West Coast Manager Editorial New Stress Needed New York KENNY KERNER ARTY GOODMAN DON DROSSELE Hollywood RON BARON On Gift Value BARRY McGOFFIN Research MIKE MARTUCCI Research Manager BOBBY SIEGEL Of Recordings Advertising Some years ago, any number of labels took advantage of the ED ADLUM gift -buying season by formulating merchandising campaigns-some Art Director WOODY HARDING of them elaborate, some modest-that stressed the continuing pleasure derived by the recipient of a recording. -

Statement Necklace with V Neck Dress

Statement Necklace With V Neck Dress Unreportable Marcio heel-and-toe or codifying some hutch ad-lib, however wrongful Ebenezer slurs quixotically or hent. Apologetic and olid Les relaxes her Almagest interrogating certain or preoccupies moreover, is Gustave multivocal? Mauritz whipsawed spiritoso. This marvelous collection before purchasing through a statement necklace should add volume on necklaces worn over the loan simply a couple of what type of On the same lines, while also drawing attention away from your neck and chest. Better than the length for my money went over a v necklace neck dress with statement earrings in baroque jewelry box! Thanks a drawer for divorce the wonderful writings! Want to buy me a coffee? Our job open to solution them but look fit feel good from different events in their lives no matter the big animal small. Statement necklace and be true, classic style and sometimes i ever done to find effective tricks will suit your neck rather than rubies or stacks of! Instance whereas the URL. This sin is heavily bejeweled with clear crystals that title shine right in every light. If you can maintain that necklace goes with jewelry with rigid angles rather large or a neck and chic look! Either a short necklace or a collar would work well with the sweetheart neckline. Go with necklaces are dressing with your necklace with a big jewelry? Take advantage of this feature by experimenting with various necklace styles. Your dress with. You to dress is known to wear statement pieces of neck sweaters hanging pendants. All women with this as well with a neck, or statement necklace with v neck dress bares your look even in line of necklace with each time after reading your cleavage. -

Charles Kleibacker, Master of the Bias Cut; Designs, Construction and Techniques

CHARLES KLEIBACKER, MASTER OF THE BIAS CUT; DESIGNS, CONSTRUCTION AND TECHNIQUES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Joycelyn Falsken, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Professor Patricia A. Cunningham, Adviser Professor Kathryn A. Jakes Professor Alice L. Conklin Curator Gayle M. Strege Copyright by Joycelyn Falsken 2008 ABSTRACT Charles Kleibacker was a fashion designer in New York City from 1960 to 1986, a time when fashion styles reflected the turmoil that occurred in society throughout those years. However, through it all Charles maintained an individual design aesthetic – soft figure-flattering bias dresses with a classic look that could be worn for years. This earned him a devoted clientele of women who purchased his designer ready-to-wear garments at top stores in New York, or were custom fit in his workshop. Because of his preference for and skill with bias, he became known as the Master of the Bias Cut. Trained in French couturier methods of construction, Kleibacker’s garments were all produced with the highest standards in fabric, construction and fit. Bias is known to be the most difficult ‘cut’ to work with when constructing garments. Charles experimented until he figured out how to solve the challenges, and then trained his workers in the exacting techniques required. Having first a career in journalism, Charles’ path to fashion was in “no way normal” and his approach to his business and the industry was not the norm either. Starting small, through much determination and sacrifice, he overcame many obstacles to produce garments engineered for an enduring and graceful artistry. -

Flanagan's Running Club – Issue 15

Flanagan's Running Club – Issue 15 Introduction The first rule of Flanagan's Running Club is everyone should talk about Flanagan's Running Club! Feel free to forward on to anyone you want, tell people about it the works, and just get them to sign up. Can I ask you all a favour, please can you review my book on Inkitt, and the link is below. Even if you don’t take time to read it properly, please flick through a few chapters, give it ratings and a review and vote for it please. It may help me get it published. https://www.inkitt.com/stories/thriller/201530 On This Day – 31st October 1922 – Benito Mussolini is made Prime Minister of Italy 1984 – Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi is assassinated by two Sikh security guards. Riots break out in New Delhi and other cities and around 3,000 Sikhs are killed. 2011 – The global population of humans reaches seven billion. This day is now recognized by the United Nations as the Day of Seven Billion. It’s Saci Day in Brazil It’s also World Savings Day And it’s World Cities Day Mapping The London Year 1795 – The poet John Keats is born in Moorgate. Keats’ parent both died by the time he was 14 (his father from falling from a horse and his mother from tuberculosis), and he was sent to live with his grandmother in Edmonton. Keats was left £800 (the equivalent of about £34,000 today) by his grandfather and a share of a legacy from his mother of £8,000 (about £340,000 today) but was apparently never told of either, as he never applied for any of the money. -

Polydor Records Discography 3000 Series

Polydor Records Discography 3000 series 25-3001 - Emergency! - The TONY WILLIAMS LIFETIME [1969] (2xLPs) Emergency/Beyond Games//Where/Vashkar//Via The Spectrum Road/Spectrum//Sangria For Three/Something Special 25-3002 - Back To The Roots - JOHN MAYALL [1971] (2xLPs) Prisons On The Road/My Children/Accidental Suicide/Groupie Girl/Blue Fox//Home Again/Television Eye/Marriage Madness/Looking At Tomorrow//Dream With Me/Full Speed Ahead/Mr. Censor Man/Force Of Nature/Boogie Albert//Goodbye December/Unanswered Questions/Devil’s Tricks/Travelling PD 2-3003 - Revolution Of The Mind-Live At The Apollo Volume III - JAMES BROWN [1971] (2xLPs) Bewildered/Escape-Ism/Get Up, Get Into It, Get Involved/Get Up I Feel Like Being A Sex Machine/Give It Up Or Turnit A Loose/Hot Pants (She Got To Use What She Got To Need What She Wants)/I Can’t Stand It/I Got The Feelin’/It’s A New Day So Let A Man Come In And Do The Popcorn/Make It Funky/Mother Popcorn (You Got To Have A Mother For Me)/Soul Power/Super Bad/Try Me [*] PD 2-3004 - Get On The Good Foot - JAMES BROWN [1972] (2xLPs) Get On The Good Foot (Parts 1 & 2)/The Whole World Needs Liberation/Your Love Was Good For Me/Cold Sweat//Recitation (Hank Ballard)/I Got A Bag Of My Own/Nothing Beats A Try But A Fail/Lost Someone//Funky Side Of Town/Please, Please//Ain’t It A Groove/My Part-Make It Funky (Parts 3 & 4)/ Dirty Harri PD 2-3005 - Ten Years Are Gone - JOHN MAYALL [1973] (2xLPs) Ten Years Are Gone/Driving Till The Break Of Dawn/Drifting/Better Pass You By//California Campground/Undecided/Good Looking