Download the Publication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liberal Leadership – the Public’S Choice

Liberal Leadership – The Public’s Choice September 14, 2006 Methodology Survey of 1000 Canadians ¾ National random sample, yielding a margin of error of +/- 3.1% ¾ Conducted in September, 2006 2 Current Vote Intention The national numbers remain very similar to the 2006 election Underneath that apparent calm, some significant movement that would affect the composition of Parliament In Quebec, Conservatives are now in a fight to hold their seats, and could lose up to seven of them to the BQ BQ could come out of an election now with 60 or more seats In Ontario, both the Conservatives (four seats) and the NDP (two seats) would lose seats to the Liberals 3 National Vote Intention Assuming a federal election were held today, which party would you vote for? The Conservative Party of Canada The Liberal Party of Canada 36 30 15 10 8 The NDP The Bloc Quebecois The Green Party 020406080100 4 National Vote Intention: Ontario/Quebec Assuming a federal election were held today, which party would you vote for? The Conservative Party of Canada 32 39 16 12 Ontario The Liberal Party of Canada The NDP The Bloc Quebecois 23 20 8 42 4 Quebec The Green Party 0 20406080100 5 What Is Driving Votes Concern about the economy is rising, and for the first time in many years is the number one priority of Canadians Health Care, and specifically wait times, remains a key issue for many people Lack of credibility on fiscal management and balanced budgets is fatal in Canadian politics now Remarkable culture shift Two perceived “hot button issues” – the Government’s -

The Victims of Substantive Representation: How "Women's Interests" Influence the Career Paths of Mps in Canada (1997-2011)

The Victims of Substantive Representation: How "Women's Interests" Influence the Career Paths of MPs in Canada (1997-2011) by Susan Piercey A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts Department of Political Science Memorial University September, 2011 St. John's Newfoundland Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre r&tirence ISBN: 978-0-494-81979-1 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-81979-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Nnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Canada's Unfinished Business

NOVEMBER 2014 Canada’s unfinished business How efforts to liberalize trade within Canada have failed and how to finally realize George Brown’s vision that Confederation would make a “citizen of one, citizen of the whole” With contributions from: Martha Hall Findlay, Anna Maria Magnifico, Ian Blue, Brian Kingston and Ailish Campbell, Monique Moreau and Brian Lee Crowley. Plus, Robin Sears profiles Saskatchewan Premier Brad Wall, a rare politician who’s unafraid to think big. Also in this issue: Stanley Hartt on whether Social Enterprise is an oxymoronic concept or the next big thing; Brian Lee Crowley says that the Ottawa shooting shows that treason isn’t going away; Benjamin Perrin on how to avoid falling into the trap of “Lone-Wolf ” terrorists Published by the Macdonald-Laurier Institute Brian Lee Crowley, Managing Director, [email protected] PublishedJames Anderson, by the Macdonald-LaurierManaging Editor, Inside Policy Institute Brian Lee Crowley,Contributing Managing writers: Director, [email protected] James Anderson, Managing Editor, Inside Policy ThomasThomas S. Axworthy S. Axworthy Tom FlanaganContributingAndrew Griffith writers:Audrey Laporte Benjamin PerrinMike Priaro Donald Barry Chrystia Freeland Ian Lee Richard Remillard DonaldThomas Barry S. Axworthy StanleyAndrew H. GriffithHartt BenjaminMike PriaroPerrin Ken Coates Guy Giorno Meredith MacDonald Robin V. Sears Brian Lee CrowleyKen CoatesDonald Barry Stephen GreenePaulStanley Kennedy H. HarttJanice MacKinnon ColinMike RobertsonPriaroMunir Sheikh Laura Dawson Andrew Griffith Linda Nazareth Alex Wilner Ken Coates Paul Kennedy Colin Robertson ElaineBrian Depow Lee Crowley Stanley H. HarttAudrey LaporteDwight Newman Roger Robinson Jeremy DepowBrian Lee Crowley Carin Holroyd Audrey LaporteGeoff Norquay Roger Robinson Carlo Dade Ian Lee Robin V. Sears Martha Hall Findlay Paul Kennedy Benjamin Perrin Carlo Dade Ian Lee Robin V. -

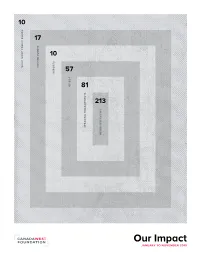

Our Impact JANUARY to NOVEMBER 2019 > Reports > What Now? Policy Briefs Contents > Op-Eds > Speaking Engagements > Hosted Events > Media Interviews

10 17 10 WHAT NOW? POLICY BRIEFS POLICY NOW? WHAT HOSTED EVENTS HOSTED 57 REPORTS OP-EDS 81 213 SPEAKING ENGAGEMENTS MEDIA INTERVIEWS Our Impact JANUARY TO NOVEMBER 2019 > Reports > What Now? policy briefs Contents > Op-eds > Speaking engagements > Hosted events > Media interviews Natural Trade Human Resources & Investment Capital Centre Centre Centre POLICY GOALS POLICY GOALS POLICY GOALS 01 08 15 Carbon and climate policies China’s relationship with Canada’s West The economics of basic skills The hierarchy of skills acquisition 02 10 15 Getting things built in Canada How to deal with trade disruption Effective partnerships between Indigenous 06 10 communities and resource firms Getting to ‘Go’: Removing regulatory Province-state relations 16 barriers to energy innovation in the age of Trump Getting ready for the 07 11 challenges of tomorrow Effective partnerships between Indigenous Building more and better strategic 16 communities and resource firms trade infrastructure Building the competency frameworks 07 11 Canada needs Getting ready for the challenges The path forward for globally competitive of tomorrow plant ingredient processing 07 11 Smart energy Trade and competitiveness 13 Getting ready for the Other challenges of tomorrow POLICY GOALS 14 17 How a U.S.-Japan trade deal affects Canada’s exports The State of Canada’s Confederation 14 20 Bold fixes to Canada’s old internal Other trade problem > Smart energy > Carbon and climate policies Natural > Getting things built in Canada > Getting to ‘Go’: Removing regulatory barriers to -

Press Release

Your Local Partner Worldwide. For Immediate Release For immediate release BOYDEN IS PLEASED TO SHARE CANADA WEST FOUNDATION APPOINTMENT NEWS – Canada West Foundation appoints Martha Hall Findlay as president and chief executive officer – CALGARY, September 8, 2016 – Martha Hall Findlay, a businessperson, lawyer and recognized thought leader, has joined the Canada West Foundation as President and CEO. Hall Findlay joins the Foundation after serving as Executive Fellow with the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy. She was also Chief Legal Officer at EnStream LP, a mobile payment joint venture of mobile providers Rogers, Bell and TELUS. Hall Findlay’s insights on critical issues such as pipelines, international trade, foreign investment, energy and the environment, and supply management have framed the national debate. Her numerous connections to the West include service on the boards of Alpine Canada and Alberta’s CKUA not-for-profit radio network. She has also served on several boards and advisory councils related to policy, resources and the environment. She served as a member of Parliament from 2008 to 2011, and as a member of the House of Commons Standing Committees for Finance; Transport; Government Operations and International Trade. She launched her 2013 campaign for the leadership of the Liberal Party of Canada in Calgary. “It was critical to the board that our new President and CEO understand the history and mission of the Canada West Foundation,” said Geoff Plant, chair of the Foundation’s board of directors. “There is no question that Martha does.” Hall Findlay said that, under her leadership, “We will continue to advocate for the West, at the national level and with other provinces and territories across Canada – reinforcing that, overwhelmingly, what is good for the West is good for Canada.” Over its four-and-a-half decades of activity, the distinguished leaders of the Canada West Foundation have contributed to a better future for western Canadians, said Plant. -

Three Liberal Challenges, Then Seize The

12 The field: Justin Trudeau, Joyce Murray, Karen McCrimmon, Martha Hall Findlay, Deborah Coyne and Martin Cauchon, at the last leadership debate in Montreal on March 23. By then, the only question remaining was who would finish second to Trudeau. Photo: Adam Scotti. he formation of Liberal Party policy heading towards the next Three Liberal T election will be shaped by three challenges, which are essentially stra- tegic in nature. This is not to suggest Challenges, then that normal policy development will be hijacked by a stand-alone strategic exercise. As always, a sense of what is Seize the Day best for the country, married with the party’s values, will obtain. There may be John Duffy an accent placed upon new and more democratic means of canvassing party opinion. Within that, however, meeting The Liberal Party can count on the record of seven years the strategic imperatives outlined below will be the critical challenge in shaping of Conservative government to help differentiate it as a the Liberal offering. governing alternative. But it also has to formulate rem- As with any opposition party, the first edies, sell them to an electorate hungry for change over and most compelling need is to build a clear, coherent and resonant critique of the heads of a balky policy elite and outperform the other the government’s policy and to create choices. It has the advantages of a policy history that an alternative that proposes to remedy the ills pointed out in that critique. squares with current trends in public sentiment and a A second, key challenge will be reconcil- leader who has the appeal of the late Jack Layton. -

38 Years Later, Aurora Optimists Turn 20 9

See page 38 years later, Aurora Optimists turn 20 9 HOT & COLD LUNCHEON BUFFET MONDAY TO FRIDAY Your local source for... 1130 A.M. - 130 P.M. Insurance Only $6.95 per person Investments Enter our weekly draw to win a FREE lunch for 2 Wealth Management 905 727 4605 www.hsfinancial.ca 15520 Yonge St., Aurora 905727-1312 Aurora’s Community Newspaper Representing www.hojoaurora.com Vol. 5 No. 30 Week of May 17, 2005 905-727-3300 Briefly Cadet inspection The 140 Aurora Royal Canadian Air Cadet Squadron will use its annual inspection to help celebrate 16 years of air cadet training in Aurora. The inspection will take place at the Aurora Community Centre, Saturday, May 28 beginning at 1 p.m. More than 500 Aurora youngsters have been through the squadron since it was founded by former Citizen of the Year Ferguson Mobbs. The inspection is the culminating event of the Air Cadet year. Several displays, created by the cadets, will be on view. During the event, the 778 Banshee Squadron Band from Richmond Hill will perform. The inspection is open to the entire community. Be there early if you want to see the march on of cadets. Bus tour The annual Aurora Historical Society bus tour will carry passengers to the Bowmanville area this year. Scheduled for Saturday, June 11, the tour will visit several historic locations in the Clarington area, including the Clarke Museum. Persons planning to make the $47 trip, which includes a buffet lunch, are asked to book seats prior to Thursday, June 9. -

No Longer Hyphenated, Liberals Cast Aside the Business Faction by Ian

No longer hyphenated, Liberals cast aside the business faction By Ian Lee, Ottawa Citizen April 15, 2013 7:15 PM Pundits and analysts agree the election of Justin Trudeau as the new leader of the Liberal Party of Canada has finally put to rest the divisive demons of internecine warfare between the Jean Chrétien and Paul Martin factions within their party. Indeed, in his acceptance speech, Trudeau urged Liberals to rediscover their “sunny ways.” And to emphasize the point, he said, “The era of hyphenated Liberals ends right here, tonight.” Consequently — so goes the argument — a united Liberal party will finally be able to return to power with its divisions behind it. However, a deeper and more empirical understanding of these events suggests Canadians witnessed the death of the historic Liberal party in Ottawa on Sunday. For a hundred years, the Liberal party was a grand coalition between “red” or social liberals and “blue” or business liberals who worked together very effectively to become Canada’s “natural governing party.” It is not fully understood by many analysts that while the Conservatives were historically supported by small business and other “outer” groups such as farmers, big business or “Bay Street capital” historically had far closer ties with the Liberal party. To that end, over the generations, distinguished and influential leaders from big business entered politics and became Liberal cabinet members. C.D. Howe under Louis St. Laurent, Robert Winters under Lester Pearson, John Turner, Donald Johnston and Roy MacLaren under Pierre Trudeau, John Manley under Chrétien, Martha Hall Findlay under Martin. -

The Liberal Leadership Race

The Liberal Leadership Race www.ekos.com Methodology Telephone survey of members of The Liberal Party of Canada in Quebec and Ontario Interviews were conducted between September 18 and 20, 2006 With a randomly selected sample of 1053, results are valid to within 3 percentage points, 19 times out of 20 - The margin of error increases when the results are sub-divided - It should also be noted that the refusal rate and other measurement errors could also increase the margin of error Attention to the leadership race Attention to the leadership race Q: As you are probably aware, there is currently a contest underway for the election of a new leader for the Liberal Party of Canada. How closely have you been following the race? 100 80 60 40 34 29 25 20 11 0 Not at all (1-3) Moderately (4) Quite closely (5-6) Very closely (7) Base Ontario and Quebec, Members of the Liberal Party of Canada, Sep. 19-21/06 n=1053 Attention to the race – Ontario v. Quebec party members Q: As you are probably aware, there is currently a contest underway for the election of a new leader for the Liberal Party of Canada. How closely have you been following the race? Ontario party members Quebec party members 100 80 60 40 40 32 29 30 22 21 17 20 9 0 Not at all (1-3) Moderately (4) Quite closely (5-6) Very closely (7) Base Ontario and Quebec, Members of the Liberal Party of Canada, Sep. 19-21/06 n=1053 Choice of candidate Choice of candidate Q: If you were able to vote in the Liberal leadership race, which candidate would you choose? Ontario Quebec Michael Ignatieff 25 24 27 Bob Rae 25 24 28 Stephane Dion 17 13 30 Gerard Kennedy 16 21 3 Ken Dryden 9 10 6 Martha Hall Findlay 3 3 0 Joe Volpe 2 2 2 Scott Brison 2 2 1 Hedy Fry 0 0 0 Other 1 0 2 0 10 20 30 40 50 Decideds only: 29 per cent answered “DK/NR” Base Ontario and Quebec, Members of the Liberal Party of Canada, Sep. -

Partie I, Vol. 142, No 11, Édition Spéciale ( 89Ko)

EXTRA Vol. 142, No. 11 ÉDITION SPÉCIALE Vol. 142, no 11 Canada Gazette Gazette du Canada Part I Partie I OTTAWA, MONDAY, OCTOBER 27, 2008 OTTAWA, LE LUNDI 27 OCTOBRE 2008 CHIEF ELECTORAL OFFICER DIRECTEUR GÉNÉRAL DES ÉLECTIONS CANADA ELECTIONS ACT LOI ÉLECTORALE DU CANADA Return of Members elected at the 40th general election Rapport de députés(es) élus(es) à la 40e élection générale Notice is hereby given, pursuant to section 317 of the Canada Avis est par les présentes donné, conformément à l’article 317 Elections Act, that returns, in the following order, have been de la Loi électorale du Canada, que les rapports, dans l’ordre received of the election of Members to serve in the House of ci-dessous, ont été reçus relativement à l’élection de députés(es) à Commons of Canada for the following electoral districts: la Chambre des communes du Canada pour les circonscriptions ci-après mentionnées : Electoral Districts Members Circonscriptions Députés(es) Rosemont—La Petite-Patrie Bernard Bigras Rosemont—La Petite-Patrie Bernard Bigras Nepean—Carleton Pierre Poilievre Nepean—Carleton Pierre Poilievre Pontiac Lawrence Cannon Pontiac Lawrence Cannon Trinity—Spadina Olivia Chow Trinity—Spadina Olivia Chow Victoria Denise Savoie Victoria Denise Savoie Thornhill Peter Kent Thornhill Peter Kent Edmonton—Mill Woods— Mike Lake Edmonton—Mill Woods— Mike Lake Beaumont Beaumont Edmonton—St. Albert Brent Rathgeber Edmonton—St. Albert Brent Rathgeber Leeds—Grenville Gord Brown Leeds—Grenville Gord Brown Wellington—Halton Hills Michael Chong Wellington—Halton -

Core 1..10 Journalweekly (PRISM

HOUSE OF COMMONS OF CANADA CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES DU CANADA 40th PARLIAMENT, 1st SESSION 40e LÉGISLATURE, 1re SESSION Journals Journaux No. 1 No 1 Tuesday, November 18, 2008 Le mardi 18 novembre 2008 10:00 a.m. 10 heures Today being the first day of the meeting of the First Session of Le Parlement se réunit aujourd'hui pour la première fois de la the 40th Parliament for the dispatch of business, Ms. Audrey première session de la 40e législature, pour l'expédition des O'Brien, Clerk of the House of Commons, and Mr. Marc Bosc, affaires. Mme Audrey O'Brien, Greffière de la Chambre des Deputy Clerk of the House of Commons, Commissioners communes, et M. Marc Bosc, Sous-greffier de la Chambre des appointed per dedimus potestatem for the purpose of communes, commissaires nommés en vertu d'une ordonnance, administering the oath to Members of the House of Commons, dedimus potestatem, pour faire prêter serment aux députés de la attending according to their duty, Ms. Audrey O'Brien laid upon Chambre des communes, sont présents dans l'exercice de leurs the Table a list of the Members returned to serve in this Parliament fonctions. Mme Audrey O'Brien dépose sur le Bureau la liste des received by her as Clerk of the House of Commons from and députés qui ont été proclamés élus au Parlement, liste attestée et certified under the hand of Mr. Marc Mayrand, Chief Electoral signée par M. Marc Mayrand, directeur général des élections, et Officer (Sessional Paper No. 8530-401-01). qu'elle a reçue en sa qualité de Greffière de la Chambre des communes (document parlementaire no 8530-401-01). -

Our Impact 2018 > Reports > What Now? Policy Briefs > Op-Eds Contents > Speaking Engagements > Hosted Events > Media Interviews

8 8 12 WHAT NOW? POLICY BRIEFS POLICY NOW? WHAT HOSTED EVENTS HOSTED 49 REPORTS OP-EDS 85 354 SPEAKING ENGAGEMENTS MEDIA INTERVIEWS Our Impact 2018 > Reports > What Now? policy briefs > Op-eds Contents > Speaking engagements > Hosted events > Media interviews Natural Trade Human Resources & Investment Capital Centre Centre Centre POLICY GOALS POLICY GOALS POLICY GOALS 01 07 20 Getting energy infrastructure The NAFTA ‘Just in Case’ Plan Reducing friction in the built – responsibly Canadian labour market 14 05 20 New trade horizons Getting electricity right in the Asia-Pacific New, different work for laid off oil and gas workers 05 16 21 Successful Indigenous China resource partnerships Literacy skill loss – and why it matters 18 06 Building more and better 22 From ‘no’ to ‘go’ on innovation strategic trade infrastructure and regulatory policy Successful Indigenous resource partnerships 18 Conditions on foreign investment 18 23 How to deal with other trade disruption 19 The plant protein opportunity > Getting energy infrastructure Natural built – responsibly > Getting electricity right > Successful Indigenous Resources resource partnerships > From ‘no’ to ‘go’ on innovation Centre and regulatory policy Op-eds Can we trust Canada’s energy processes? Getting energy Globe and Mail infrastructure built Are more pipelines in the public interest? Martha Hall Findlay Martha Hall Findlay 20-Feb-18 – responsibly Alberta Views POLICY GOAL 17-Dec-18 On Trans Mountain, Trudeau needs to become a leader for all of Canada Bill C-69 is the antithesis of