Imlllfl~Ii!Ooiiillil 3 ACKU 00000138 7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Land of Five Rivers and Sindh by David Ross

THE LAND OFOFOF THE FIVE RIVERS AND SINDH. BY DAVID ROSS, C.I.E., F.R.G.S. London 1883 Reproduced by: Sani Hussain Panhwar The land of the five rivers and Sindh; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 1 TO HIS EXCELLENCY THE MOST HONORABLE GEORGE FREDERICK SAMUEL MARQUIS OF RIPON, K.G., P.C., G.M.S.I., G.M.I.E., VICEROY AND GOVERNOR-GENERAL OF INDIA, THESE SKETCHES OF THE PUNJAB AND SINDH ARE With His Excellency’s Most Gracious Permission DEDICATED. The land of the five rivers and Sindh; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 2 PREFACE. My object in publishing these “Sketches” is to furnish travelers passing through Sindh and the Punjab with a short historical and descriptive account of the country and places of interest between Karachi, Multan, Lahore, Peshawar, and Delhi. I mainly confine my remarks to the more prominent cities and towns adjoining the railway system. Objects of antiquarian interest and the principal arts and manufactures in the different localities are briefly noticed. I have alluded to the independent adjoining States, and I have added outlines of the routes to Kashmir, the various hill sanitaria, and of the marches which may be made in the interior of the Western Himalayas. In order to give a distinct and definite idea as to the situation of the different localities mentioned, their position with reference to the various railway stations is given as far as possible. The names of the railway stations and principal places described head each article or paragraph, and in the margin are shown the minor places or objects of interest in the vicinity. -

Parcel Post Compendium Online Pakistan Post PKA PK

Parcel Post Compendium Online PK - Pakistan Pakistan Post PKA Basic Services CARDIT Carrier documents international Yes transport – origin post 1 Maximum weight limit admitted RESDIT Response to a CARDIT – destination Yes 1.1 Surface parcels (kg) 50 post 1.2 Air (or priority) parcels (kg) 50 6 Home delivery 2 Maximum size admitted 6.1 Initial delivery attempt at physical Yes delivery of parcels to addressee 2.1 Surface parcels 6.2 If initial delivery attempt unsuccessful, Yes 2.1.1 2m x 2m x 2m No card left for addressee (or 3m length & greatest circumference) 6.3 Addressee has option of paying taxes or Yes 2.1.2 1.5m x 1.5m x 1.5m Yes duties and taking physical delivery of the (or 3m length & greatest circumference) item 2.1.3 1.05m x 1.05m x 1.05m No 6.4 There are governmental or legally (or 2m length & greatest circumference) binding restrictions mean that there are certain limitations in implementing home 2.2 Air parcels delivery. 2.2.1 2m x 2m x 2m No 6.5 Nature of this governmental or legally (or 3m length & greatest circumference) binding restriction. 2.2.2 1.5m x 1.5m x 1.5m Yes (or 3m length & greatest circumference) 2.2.3 1.05m x 1.05m x 1.05m No 7 Signature of acceptance (or 2m length & greatest circumference) 7.1 When a parcel is delivered or handed over Supplementary services 7.1.1 a signature of acceptance is obtained Yes 3 Cumbersome parcels admitted No 7.1.2 captured data from an identity card are Yes registered 7.1.3 another form of evidence of receipt is No Parcels service features obtained 5 Electronic exchange of information -

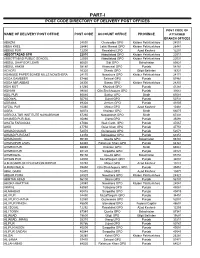

Part-I: Post Code Directory of Delivery Post Offices

PART-I POST CODE DIRECTORY OF DELIVERY POST OFFICES POST CODE OF NAME OF DELIVERY POST OFFICE POST CODE ACCOUNT OFFICE PROVINCE ATTACHED BRANCH OFFICES ABAZAI 24550 Charsadda GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24551 ABBA KHEL 28440 Lakki Marwat GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28441 ABBAS PUR 12200 Rawalakot GPO Azad Kashmir 12201 ABBOTTABAD GPO 22010 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22011 ABBOTTABAD PUBLIC SCHOOL 22030 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22031 ABDUL GHAFOOR LEHRI 80820 Sibi GPO Balochistan 80821 ABDUL HAKIM 58180 Khanewal GPO Punjab 58181 ACHORI 16320 Skardu GPO Gilgit Baltistan 16321 ADAMJEE PAPER BOARD MILLS NOWSHERA 24170 Nowshera GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24171 ADDA GAMBEER 57460 Sahiwal GPO Punjab 57461 ADDA MIR ABBAS 28300 Bannu GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28301 ADHI KOT 41260 Khushab GPO Punjab 41261 ADHIAN 39060 Qila Sheikhupura GPO Punjab 39061 ADIL PUR 65080 Sukkur GPO Sindh 65081 ADOWAL 50730 Gujrat GPO Punjab 50731 ADRANA 49304 Jhelum GPO Punjab 49305 AFZAL PUR 10360 Mirpur GPO Azad Kashmir 10361 AGRA 66074 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66075 AGRICULTUR INSTITUTE NAWABSHAH 67230 Nawabshah GPO Sindh 67231 AHAMED PUR SIAL 35090 Jhang GPO Punjab 35091 AHATA FAROOQIA 47066 Wah Cantt. GPO Punjab 47067 AHDI 47750 Gujar Khan GPO Punjab 47751 AHMAD NAGAR 52070 Gujranwala GPO Punjab 52071 AHMAD PUR EAST 63350 Bahawalpur GPO Punjab 63351 AHMADOON 96100 Quetta GPO Balochistan 96101 AHMADPUR LAMA 64380 Rahimyar Khan GPO Punjab 64381 AHMED PUR 66040 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66041 AHMED PUR 40120 Sargodha GPO Punjab 40121 AHMEDWAL 95150 Quetta GPO Balochistan 95151 -

List of Branches Authorized for Overnight Clearing (Annexure - II) Branch Sr

List of Branches Authorized for Overnight Clearing (Annexure - II) Branch Sr. # Branch Name City Name Branch Address Code Show Room No. 1, Business & Finance Centre, Plot No. 7/3, Sheet No. S.R. 1, Serai 1 0001 Karachi Main Branch Karachi Quarters, I.I. Chundrigar Road, Karachi 2 0002 Jodia Bazar Karachi Karachi Jodia Bazar, Waqar Centre, Rambharti Street, Karachi 3 0003 Zaibunnisa Street Karachi Karachi Zaibunnisa Street, Near Singer Show Room, Karachi 4 0004 Saddar Karachi Karachi Near English Boot House, Main Zaib un Nisa Street, Saddar, Karachi 5 0005 S.I.T.E. Karachi Karachi Shop No. 48-50, SITE Area, Karachi 6 0006 Timber Market Karachi Karachi Timber Market, Siddique Wahab Road, Old Haji Camp, Karachi 7 0007 New Challi Karachi Karachi Rehmani Chamber, New Challi, Altaf Hussain Road, Karachi 8 0008 Plaza Quarters Karachi Karachi 1-Rehman Court, Greigh Street, Plaza Quarters, Karachi 9 0009 New Naham Road Karachi Karachi B.R. 641, New Naham Road, Karachi 10 0010 Pakistan Chowk Karachi Karachi Pakistan Chowk, Dr. Ziauddin Ahmed Road, Karachi 11 0011 Mithadar Karachi Karachi Sarafa Bazar, Mithadar, Karachi Shop No. G-3, Ground Floor, Plot No. RB-3/1-CIII-A-18, Shiveram Bhatia Building, 12 0013 Burns Road Karachi Karachi Opposite Fresco Chowk, Rambagh Quarters, Karachi 13 0014 Tariq Road Karachi Karachi 124-P, Block-2, P.E.C.H.S. Tariq Road, Karachi 14 0015 North Napier Road Karachi Karachi 34-C, Kassam Chamber's, North Napier Road, Karachi 15 0016 Eid Gah Karachi Karachi Eid Gah, Opp. Khaliq Dina Hall, M.A. -

Estimated Age

The US National Counterterrorism Center is pleased to present the 2016 edition of the Counterterrorism (CT) Calendar. Since 2003, we have published the calendar in a daily planner format that provides our consumers with a variety of information related to international terrorism, including wanted terrorists; terrorist group fact sheets; technical issue related to terrorist tactics, techniques, and procedures; and potential dates of importance that terrorists might consider when planning attacks. The cover of this year’s CT Calendar highlights terrorists’ growing use of social media and other emerging online technologies to recruit, radicalize, and encourage adherents to carry out attacks. This year will be the last hardcopy publication of the calendar, as growing production costs necessitate our transition to more cost- effective dissemination methods. In the coming years, NCTC will use a variety of online and other media platforms to continue to share the valuable information found in the CT Calendar with a broad customer set, including our Federal, State, Local, and Tribal law enforcement partners; agencies across the Intelligence Community; private sector partners; and the US public. On behalf of NCTC, I want to thank all the consumers of the CT Calendar during the past 12 years. We hope you continue to find the CT Calendar beneficial to your daily efforts. Sincerely, Nicholas J. Rasmussen Director The US National Counterterrorism Center is pleased to present the 2016 edition of the Counterterrorism (CT) Calendar. This edition, like others since the Calendar was first published in daily planner format in 2003, contains many features across the full range of issues pertaining to international terrorism: terrorist groups, wanted terrorists, and technical pages on various threat-related topics. -

II Pakistani Schedule Banks Branches As on 31 December 2010

Appendix - II Pakistani Schedule Banks Branches As on 31st December 2010 Allied Bank Ltd. -Noor Hayat Colony -Mohar Sharif Road (806) Bheli Bhattar (A.K.) Chitral Abbaspur 251 RB Bandla Bhiria Chungpur (A.K.) Dadu Abbottabad (4) Burewala (2) -Bara Towers, Jinnahabad -Grain Market Dadyal (A.K) (2) -Pineview Road -Housing Scheme -College Road -Supply Bazar -Samahni Ratta Cross -The Mall Chak Jhumra Chak Naurang Daharki Adda Johal Chak No. 111 P Danna (A.K.) Adda Nandipur Rasoolpur Chak No. 122/JB Nurpur Danyor Bhal Chak No. 142/P Bangla Darband Adda Pansra Manthar Dargai Adda Sarai Mochiwal Chak No. 220 RB Darhal Gaggan Adda Thikriwala Chak No. 272 HR Fortabbas Daroo Jabagai Kombar Alipur Chak No. 280/JB (Dawakhri) Ahmed Pur East Chak No. 34/TDA Daska (2) Akalgarh (A.K) Chak No. 354 -Kutchery road Arifwala Chak No. 44/N.B. -Village budha Attock (Campbellpur) Chak No. 509 GB Bagh (A.K) Chak No. 61 RB Daurandi (A.K.) Bahawalnagar Chak No. 76 RB Deenpur Chak No. 80 SB Deh Uddhi Bahawalpur (5) Chak No. 88/10 R Dinga Chak No. 89/6-R -Com. Area Sattelite Town Chakothi -Dubai Chowk Dera Ghazi Khan (2) -Farid Gate -Azmat Road -Ghalla Mandi Chakwal (3) -Model Town -Settelite Town -Mohra Chinna -Sabzimandi Dera Ismail Khan (3) Bakhar Jamali Mori Talu -Talagang Road -Circular Road Bhawanj -Commissionery Bazar Balagarhi Chaman -Faqirani Gate (Muryali) Balakot Chaprar Baldher Charsadda Dhamke (Faisalabad) Bucheke Chaskswari (A.K) Dhamke (Sheikhupura) Chattar (A.K) Dhangar Bala (A.K) Chhatro (A.K.) Bannu (2) Dheed Wal -Chai Bazar (Ghalla Mandi) Dhudial (Punjab) -Preedy Gate Chichawatni (2) Dina -College Road Dipalpur Barja Jandala (A.K) -Railway Road Dir Batkhela Dunyapur Behari Agla Mohra (A.K.) Chilas Ellahabad Bewal Eminabad More Bhagowal Chiniot (2) Bhakkar -Muslim Bazar (Main) Faisalabad (20) Bhaleki (Phularwan Chowk) -Sargodha Road -Akbarabad -Chibban Road Bhalwal (2) Chishtian (2) -Factory Area -Grain Market -Grain Market 335 -Ghulam Muhammad Abad -Grand Trunk Road -Bara Kahu Colony -Rehman Saheed Road -Blue Area -Gole Cloth Market -Shah Daula Road. -

Audit Report on the Accounts of Pakistan Railways Audit Year 2015-16

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF PAKISTAN RAILWAYS AUDIT YEAR 2015-16 AUDITOR - GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. ABBREVIATIONS & ACRONYMS i & ii PREFACE iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY iv SUMMARY TABLES I Audit Work Statistics xi II Audit Observations Regarding Financial Management xi III Outcome Statistics xii IV Irregularities Pointed out xiii V Cost Benefit Analysis xiii CHAPTER 1 Public Financial Management Issues 1 Financial Advisor & Chief Accounts Officer, Pakistan Railways CHAPTER 2 Ministry of Railways 8 2.1 Introduction of Ministry 8 2.2 Comments on Budget & Accounts 9 2.3 Brief Comments on the status of Compliance with PAC 17 directives 2.4 AUDIT PARAS Misappropriations 18 Non-Production of Record 23 Irregularity & Non-Compliance 25 Performance 68 Internal Control Weaknesses 90 Others 101 Annexure-1 Pie Chart Table 111-112 Annexure-II Detail of Recoverables 113-124 Annexure-III MFDAC Paras 125-127 Annexure-IV Detail of irregular expenditure on pay & allowances 128 ABBREVIATIONS & ACRONYMS AEN Assistant Executive Engineer AGM Additional General Manager APPM Accounting Policies and Procedures Manual BPS Basic Pay Scale CA Certification Audit CCM Chief Commercial Manager CCTV Closed Circuit Television CFT Cubic Feet CSR Composite Schedule of Rates CHOT Chiniot DAC Departmental Accounts Committee DAEE Divisional Assistant Electrical Engineer DCOS District Controller of Stores DE Locomotive Diesel Electric Locomotive DEE Divisional Electrical Engineer DG Set Diesel Generator Sets DGM Deputy General Manager DRF Depreciation Reserve -

Archaeological Sites and Historical Monuments Along the Khyber Pass Javed Iqbal

Ancient Pakistan, Vol. XXV (2014) 41 Where History Meets Archaeology: Archaeological Sites and Historical Monuments along the Khyber Pass Javed Iqbal Abstract: History and Archaeology are inseparable twins. Archaeological data needs to be explained with the help of historical facts and figures while historical narrations always need to be strengthened with tangible evidence in the shape of solid archaeological proofs excavated by archaeologists and described in their style and structure. The historical and archaeological monuments in different parts of Pakistan are a national heritage and potentially a source of earning if foreign tourism is revived and promoted in this country that so badly need a soft image to regain its place among the civilized nations of the world. Some of these treasures are situated in Khyber Pass and with a little effort and projection these can help convert the tourism department into tourism industry in Pakistan, bringing in foreign tourists and economic opportunities for the people. These monuments are our national heritage and it is our duty as historians and archaeologists to save them from further destruction at the hands of both men and nature and to give them the projection and appreciation that they so rightly deserve. Most of these monuments are a perfect example of a closer link and bond between the discipline of History and Archaeology, historians doing their part of research and archaeologists supplementing their work with technical aspects of their style and structure. This is where History meets Archaeology. The paper is an effort to bring to light the important but neglected historical sites and archaeological monuments in Khyber pass with a brief history so that it becomes an inspiration for the young and budding researchers in both fields, history as well as archaeology, to explore the hidden aspects of these treasures and to make them more known to the people all over the world. -

Pakistan Bait-Ul-Mal

PAKISTAN BAIT-UL-MAL National Center(s) for Rehabilitation of Child Labour (NCsRCL) Province Khyber Pakhtunkhwa S# District Address of NCsRCL 1 Peshawar Pattan Colony, Near Ghalla Godown, Kohat Road Tel:0332-9211201 2 Nowshera Near Shah Gul Baba Arat, Mardan Road, Nowshera Klan Tel:0321-9697141 3 Charsadda Quaidabad, Mardan Road, Charsadda Tel:0301-8908382 4 Mardan City Moh. Muslim Abad, Kas Korona, Mardan Tel:0345-9239479 5 Takht Bhai Mohallah Mira Khan. Malakand Road, Takht Bhai, Mardan Tel:0301-8767752 6 Hari Pur Sector #2, Kangra Colony, Hari Pur Tel:0300-5619286 7 Swabi Swatiano Mohallah, Topi Tel:0300-5653660 8 Kohat Happy Valley, KCB-1/93, Peshawar Road. Tel:0922-515472 9 Hangu House No. 1141, Mohallah Ganjiano Killi, Hangu Tel:0332-9643770 10 Abbottabad House No. 2719 M/C 2099, Link Road, Abbottabad. Tel:- 11 Mansehra Village Bhar Kand, Uggi Road, Tehsil & District Mansehra. Tel:0331-9284380 12 Tank Tank City, Tank Tel:0343-9296314 13 D.I.Khan Quaid-e-Azam Road, Banglow No. 1, Cantt. D.I. Khan Tel:0333-9954370 14 Bannu Hinjal, Bannu City Tel:0301-8085965 15 Pir Baba Near Pir Baba, Main Bazar, Buner Tel:0333-9690736 16 Swari Dewana baba road, Swari Buner Tel:0333-9690736 17 Swat St. No.1, Sharif Abad, Mingora, District Swat Tel:0344-9603081 18 Shangla Alpuri Village, Shanglapar Tel:0996-850813 19 Chitral Jung Bazar Payan, Near Polo Ground, Chitral Tel:0302-3161977 20 Mohmand Agency Chanda Bazar Ghalanai Tel:0346-9858682 21 Orakzai Agency Main Bazar Kalaya, Orakzai Agency Tel:0334-8287908 22 Bajaur Agency Near Old Hospital, Sabzi Mandi, Khar Tel:0303-8260940 23 Landi Kotal Main Landi Kotal Bazar, Khyber Agency Tel:0346-9720072 24 Jamrud Tidi, New Abadi, Jamrud, Khyber Agency Tel:0344-9846468 Province Punjab S# District Name Address of NCsRCL 1 Rawalpindi Bait-us-Sada Colony, Misrial Road, Rawalpindi Cantt Tel:0301-5867911 2 Dhoke Fateh, Kamal Pur Sayedan, near tube well District Attock Tel:0336-5778910 Attock Hassanabdal Mohallah Iqbnal Nagar Tehsil Hassan abdaal District Attock Tel:0322- 3 5715770/ 0322-5722019 H. -

Pak Pos and RMS Offices 3Rd Ed 1962

Instructions for Sorting Clerks and Sorters ARTICLES ADDRl!SSBD TO TWO PosT-TOWNS.-If the address Dead Letter Offices receiving articles of the description re 01(an article contains the names of two post-town, the article ferred in this clause shall be guided by these instructions so far should, as a general rule, be forwarded to whichever of the two as the circumstances of each case admit of their application. towns is named last unless the last post-town- Officers employed in Dead Letter Offices are selected for their special fitness for the work and are expected to exercise intelli ( a) is obviously meant to indicate the district, in which gence and discretion in the disposal of articles received by case the article should be . forwar ~ ed ~ · :, the first them. named post-town, e. g.- A. K. Malik, Nowshera, Pes!iaivar. 3. ARTICLES ADDRESSED TO A TERRITORIAL DIVISION WITH (b) is intended merely as a guide to the locality, in which OUT THE ADDITION OF A PosT-TOWN.-If an article is addressed case the article should be forwarded to the first to one of the provinces, districts, or other territorial divisions named post-town, e. g.- mentioned in Appendix I and the address does not contain the name of any post-town, it should be forwarded to the post-town A. U. Khan, Khanpur, Bahawalpur. mentioned opposite, with the exception of articles addressed to (c) Case in which the first-named post-town forms a a military command which are to be sent to its headquarters. component part of the addressee's designation come under the general rule, e. -

Second Science Education Sector Project

Completion Report Project Number: 26326 Loan Number: 1534-PAK[SF] November 2007 PAKISTAN: Second Science Education Sector Project CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Currency Unit – Pakistan rupee/s (PRe/PRs) At Appraisal At Project Completion (31 July 1997) (30 June 2007) PRe1.00 = $0.025 $0.017 $1.00 = PRs40.56 PRs60.00 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank BME – benefit monitoring and evaluation EA – executing agency ECNEC – Executive Committee of the National Economic Council FATA – Federally Administered Tribal Areas FCU – federal coordinating unit IPSET – Institute for the Promotion of Science Education and Training M&E – monitoring and evaluation MOE – Ministry of Education MPL – multipurpose laboratory MRR – mathematics resource room NEEC – National Education Equipment Center NISTE – National Institute for Science and Technical Education NSAC – National Scientific Advisory Committee NSC – National Steering Committee NWFP – North-West Frontier Province OECF – Overseas Economic Cooperation Fund PCC – provincial coordination committee PC-I – Planning Commission Proforma I PED – provincial education department PIU – project implementation unit RRP – report and recommendation of the President SAP – Social Action Programme SEC – science education center SHS – science high school NOTES (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the Government of Pakistan and its agencies ends on 30 June. FY before a calendar year denotes the year in which the fiscal year ends, e.g., FY2007 ends on 30 June 2007. (ii) In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. (iii) “Government” refers to the Government of Pakistan. Vice President L. Jin, Operations 1 Director General J. Miranda, Central and West Asia Regional Department Director P. Fedon, Pakistan Resident Mission Team leader S. Abbas, Senior Project Implementation Officer, Pakistan Resident Mission Team member N. -

ECO Railway Network Development Plan

A report for the ECO Secretariat ECO Railway Network Development Plan CORRIDOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES FOR THE PROJECT MANAGEMENT UNIT (PMU) UNDER THE AEGIS OF THE JOINT ECO/IDB PROJECT ON IMPLEMENTATION OF THE TTFA Professor Dimitrios Tsamboulas Consultant June 2012 1 Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................3 1.1 Background.......................................................................................................3 1.2 Scope of the Report ..........................................................................................3 1.3 Report Outline ...................................................................................................3 2.DATA COLLECTION ..............................................................................................5 2.1 Introduction .......................................................................................................5 2.2 Part 1-ECO Rail Routes ....................................................................................5 2.3 Part 2-ECO rail transportation infrastructure projects ........................................5 2.4 Part 3-Country Reports .....................................................................................6 3.IDENTIFICATION OF PRIORITY ECO RAIL ROUTES...........................................7 3.1 Introduction .......................................................................................................7 3.2 Methodology for identification