Dumont and the Birth of American Television

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deepwater Horizon Natural Resources Damage Assessment

Deepwater Horizon Natural Resources Damage Assessment Water Column Technical Working Group Examining the Scope of Spill impacts to Early Stage Fishes in the US Economic Exclusion Zone John A Quinlan\ Cherie Keller^, David Hanisko^ Conor McManus^ Jennifer Kunzieman^, Dave Foley®, Joaquin Trinanes^, Daniel Hahn®, and Mary Christman^ ^ NOAA-NMFS Southeast Fisheries Science Center, 75 Virginia Beach Drive, Miami, FL 33149 ^ MCC Statisticai Consuiting LLC, Gainesviiie, FL 32605 ^ NOAA-NMFS SEFSC Mississippi Laboratories, 3209 Frederic Street, Pascagoula, MS 39567 ^ RPS-ASA, 55 Village Square Drive, South Kingstown, Rl 02879 ^ NOAA-ORR Assessment and Restoration Division, Southeast/Gulf of Mexico Region, St. Petersburg, FL ® NOAA-NMFS SWFSC Environmental Research Division, Monterey, CA 93940 ^ NOAA-OAR Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, 4301 RIckenbacker Causeway, Miami, FL 33149 Abstract Statistical modeling was used to create spatio-temporal estimates/maps of mean larval fish relative abundance in the US Economic Exclusion Zone (EEZ) of the Gulf of Mexico for the period of late April to early August, 2010. These estimates were used to calculate a nondimensional number that represents the proportion, or percentage, of predicted larval fish in the EEZ that were potentially exposed to oil from the Deepwater Horizon incident. The proportion exposed is a function of the 'production schedule' of the population, the location and timing of that productivity, and the spatio-temporal distribution of surface oil. Introduction The Deepwater Horizon Incident remains the largest oil spill in a marine environment in United States history. Vast quantities of oil and other contaminants were discharged into the northern Gulf of Mexico from late April to mid-July in 2010. -

Senior Women's Performances of Sexuality

“DUSTY MUFFINS”: SENIOR WOMEN’S PERFORMANCES OF SEXUALITY A Thesis by EVLEEN MICHELLE NASIR Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2012 Major Subject: Performance Studies “Dusty Muffins”: Senior Women’s Performances of Sexuality Copyright 2012 Evleen Michelle Nasir “DUSTY MUFFINS”: SENIOR WOMEN’S PERFORMANCES OF SEXUALITY A Thesis by EVLEEN MICHELLE NASIR Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved by: Chair of Committee, Kirsten Pullen Committee Members, Judith Hamera Harry Berger Alfred Bendixen Head of Department, Judith Hamera August 2012 Major Subject: Performance Studies iii ABSTRACT “Dusty Muffins”: Senior Women’s Performance of Sexuality. (August 2012) Evleen Michelle Nasir, B.A., Texas A&M University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Kirsten Pullen There is a discursive formation of incapability that surrounds senior women’s sexuality. Senior women are incapable of reproduction, mastering their bodies, or arousing sexual desire in themselves or others. The senior actresses’ I explore in the case studies below insert their performances of self and their everyday lives into the large and complicated discourse of sex, producing a counter-narrative to sexually inactive senior women. Their performances actively embody their sexuality outside the frame of a character. This thesis examines how senior actresses’ performances of sexuality extend a discourse of sexuality imposed on older woman by mass media. These women are the public face of senior women’s sexual agency. -

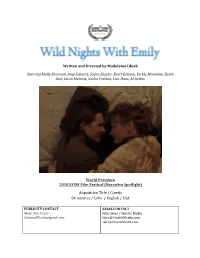

Written and Directed by Madeleine Olnek

Written and Directed by Madeleine Olnek Starring Molly Shannon, Amy Seimetz, Susan Ziegler, Brett Gelman, Jackie Monahan, Kevin Seal, Dana Melanie, Sasha Frolova, Lisa Haas, Al Sutton World Premiere 2018 SXSW Film Festival (Narrative Spotlight) Acquisition Title / Cinetic 84 minutes / Color / English / USA PUBLICITY CONTACT SALES CONTACT Mary Ann Curto John Sloss / Cinetic Media [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THE FILM PRESS MATERIALS CONTACT and FILM CONTACT: Email: [email protected] DOWNLOAD FILM STILLS ON DROPBOX/GOOGLE DRIVE: For hi-res press stills, contact [email protected] and you will be added to the Dropbox/Google folder. Put “Wild Nights with Emily Still Request” in the subject line. The OFFICIAL WEBSITE: http://wildnightswithemily.com/ For news and updates, click 'LIKE' on our FACEBOOK page: https://www.facebook.com/wildnightswithemily/ "Hilarious...an undeniably compelling romance. " —INDIEWIRE "As entertaining and thought-provoking as Dickinson’s poetry.” —THE AUSTIN CHRONICLE SYNOPSIS THE STORY SHORT SUMMARY Molly Shannon plays Emily Dickinson in " Wild Nights With Emily," a dramatic comedy. The film explores her vivacious, irreverent side that was covered up for years — most notably Emily’s lifelong romantic relationship with another woman. LONG SUMMARY Molly Shannon plays Emily Dickinson in the dramatic comedy " Wild Nights with Emily." The poet’s persona, popularized since her death, became that of a reclusive spinster – a delicate wallflower, too sensitive for this world. This film explores her vivacious, irreverent side that was covered up for years — most notably Emily’s lifelong romantic relationship with another woman (Susan Ziegler). After Emily died, a rivalry emerged when her brother's mistress (Amy Seimetz) along with editor T.W. -

Middle Grade Indicators of Readiness in Chicago Public Schools

RESEARCH REPORT NOVEMBER 2014 Looking Forward to High School and College Middle Grade Indicators of Readiness in Chicago Public Schools Elaine M. Allensworth, Julia A. Gwynne, Paul Moore, and Marisa de la Torre TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Executive Summary Chapter 5 55 Who Is at Risk of Earning Less 7 Introduction Than As or Bs in High School? Chapter 1 Chapter 6 17 Issues in Developing and Indicators of Whether Students Evaluating Indicators 63 Will Meet Test Benchmarks Chapter 2 Chapter 7 23 Changes in Academic Performance Who Is at Risk of Not Reaching from Eighth to Ninth Grade 75 the PLAN and ACT Benchmarks? Chapter 3 Chapter 8 29 Middle Grade Indicators of How Grades, Attendance, and High School Course Performance 81 Test Scores Change Chapter 4 Chapter 9 47 Who Is at Risk of Being Off-Track Interpretive Summary at the End of Ninth Grade? 93 99 References 104 Appendices A-E ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors would like to acknowledge the many people who contributed to this work. We thank Robert Balfanz and Julian Betts for providing us with very thoughtful review and feedback which were used to revise this report. We also thank Mary Ann Pitcher and Sarah Duncan, at the Network for College Success, and members of our Steering Committee, especially Karen Lewis, for their valuable feedback. Our colleagues at UChicago CCSR and UChicago UEI, including Shayne Evans, David Johnson, Thomas Kelley-Kemple, and Jenny Nagaoka, were instrumental in helping us think about the ways in which this research would be most useful to practitioners and policy makers. -

PUBLIC BROADCASTING: a MEDIUM in SEARCH of SOLUTIONS John W

PUBLIC BROADCASTING: A MEDIUM IN SEARCH OF SOLUTIONS JoHN W. MACY, JR.* INTRODUCTION In its simplest and most comprehensive definition, a communications system is a process in which creative communicators become aware of the expressed and some- times unexpressed needs of the users of the system and responsively collect and provide information, entertainment, and other resources toward the satisfaction of these needs. Despite the often quoted and now popular belief that in electronic com- munications systems "the medium is the message,"' the design of a system in which the message is itself the message-and the medium is merely a means of delivering a diversity of messages of intrinsic value to the users-is a mandate for radio and television in the decade of the 1970s. This is one of the basic philosophies behind the approach of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB) as it builds and develops the public sector of broadcasting. Some time ago Robert Oppenheimer was quoted as saying, "What is new is new not because it has never been there before, but because it has changed in quality."2 This is surely what is new about the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. But to understand the nature and direction of the qualitative changes brought about by its creation and activities, it is necessary to look first at what was there before and how the Corporation came into being. I BACKGROUND OF PUBLIC BROADCASTING Over the past fifty years, the American public, through its elected representatives and otherwise, has made a series of choices to encourage the development of a public alternative in the field of communications. -

Ms Girls Athletics Info

Commerce Middle School Lady Tiger Athletics Welcome to middle school athletics! We are super excited to get the year started and to get to know your daughter(s) throughout the year. Commerce ISD has issued the following statement “In order for your daughter to participate in UIL events and/or extra-curricular activities, your daughter has to follow the Hybrid model. If your daughter is strictly online, she cannot participate in any UIL event or extra curricular activities.” We will continue to have practice EVERY morning at 6:45 a.m. throughout the year. If your daughter is playing Volleyball, she will be here every morning, ready to practice at 6:45. If your daughter is in Athletics and NOT playing volleyball, she will still need to come to Athletics every morning, ready to start at 7:30 a.m. Parents will have to provide transportation to and from practice. If it is not your daughter’s assigned day to be at school, she will need to be picked up at the end of practice. Contacts: CMS: (903)-886-3795 ext. 726 Julie Brown: 8th(Basketball)/8th (Volleyball)Grade Coach- [email protected] Kayla Collum:7th(Volleyball/Track)/7th(Basketball/Track) Coach- [email protected] Tony Henry: Head Basketball Coach- [email protected] Shelley Jones: Head Volleyball/Track Coach- [email protected] Amanda Herron: Athletic Trainer- [email protected] Jeff Davidson: Athletic Director- [email protected] Coach Brown will set up a Remind for 7th and 8th Grade Girls Athletics. All information and Updated information will be found on Remind for students and parents will be on Remind. -

The Musical Number and the Sitcom

ECHO: a music-centered journal www.echo.ucla.edu Volume 5 Issue 1 (Spring 2003) It May Look Like a Living Room…: The Musical Number and the Sitcom By Robin Stilwell Georgetown University 1. They are images firmly established in the common television consciousness of most Americans: Lucy and Ethel stuffing chocolates in their mouths and clothing as they fall hopelessly behind at a confectionary conveyor belt, a sunburned Lucy trying to model a tweed suit, Lucy getting soused on Vitameatavegemin on live television—classic slapstick moments. But what was I Love Lucy about? It was about Lucy trying to “get in the show,” meaning her husband’s nightclub act in the first instance, and, in a pinch, anything else even remotely resembling show business. In The Dick Van Dyke Show, Rob Petrie is also in show business, and though his wife, Laura, shows no real desire to “get in the show,” Mary Tyler Moore is given ample opportunity to display her not-insignificant talent for singing and dancing—as are the other cast members—usually in the Petries’ living room. The idealized family home is transformed into, or rather revealed to be, a space of display and performance. 2. These shows, two of the most enduring situation comedies (“sitcoms”) in American television history, feature musical numbers in many episodes. The musical number in television situation comedy is a perhaps surprisingly prevalent phenomenon. In her introduction to genre studies, Jane Feuer uses the example of Indians in Westerns as the sort of surface element that might belong to a genre, even though not every example of the genre might exhibit that element: not every Western has Indians, but Indians are still paradigmatic of the genre (Feuer, “Genre Study” 139). -

Expert Panelists Consider Community Development's Next Wave Intro

Expert Panelists Consider Community Development’s Next Wave Intro In spring of 2015, LISC NYC’s Executive Director, Sam Marks invited friends of LISC - top economists, policy analysts, journalists, community development gurus and current leaders of some of the city’s top community development corporations - to join staff in strategizing around critical questions facing New York’s community development sector. What can LISC NYC and its community development partners do to counter global and national trends exacerbating economic polarization? What is community development’s role in shaping the city’s upcoming neighborhood rezonings, preserving affordable housing, and, building human capital? How can the industry scale up even as it consolidates and redeploys resources to new areas and programming? Over the course of three panel discussions moderated by Marks, presenters and LISC NYC staff shed some light on next wave strategies for New York City’s neighborhoods. Panel 1: Global City/Global Trends: Panelists explained the global trends driving high real estate prices, economic polarization, gentrification and displacement and debated about the levers available to city government, LISC NYC and community developers to alleviate the harsh impacts on low and moderate income New Yorkers. Jonathan Bowles, Executive Director, Center for an Urban Future . Adam Davidson, co-founder and co-host, Planet Money . Ingrid Gould Ellen, Paulette Goddard Professor of Urban Policy and Planning, Director of the Urban Planning Program, New York University Wagner; Faculty Director, Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy . Chris Herbert, Managing Director, Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies Panel 2: Community development past, present and future: Former LISC NYC directors distilled their experiences using real estate strategies to address neighborhood issues and considered strategies to meet current challenges. -

He KMBC-ÍM Radio TEAM

l\NUARY 3, 1955 35c PER COPY stu. esen 3o.loe -qv TTaMxg4i431 BItOADi S SSaeb: iiSZ£ (009'I0) 01 Ff : t?t /?I 9b£S IIJUY.a¡:, SUUl.; l: Ii-i od 301 :1 uoTloas steTaa Rae.zgtZ IS-SN AlTs.aantur: aTe AVSí1 T E IdEC. 211111 111111ip. he KMBC-ÍM Radio TEAM IN THIS ISSUE: St `7i ,ytLICOTNE OSE YN in the 'Mont Network Plans AICNISON ` MAISHAIS N CITY ive -Film Innovation .TOrEKA KANSAS Heart of Americ ENE. SEDALIA. Page 27 S CLINEON WARSAW EMROEIA RUTILE KMBC of Kansas City serves 83 coun- 'eer -Wine Air Time ties in western Missouri and eastern. Kansas. Four counties (Jackson and surveyed by NARTB Clay In Missouri, Johnson and Wyan- dotte in Kansas) comprise the greater Kansas City metropolitan trading Page 28 Half- millivolt area, ranked 15th nationally in retail sales. A bonus to KMBC, KFRM, serv- daytime ing the state of Kansas, puts your selling message into the high -income contours homes of Kansas, sixth richest agri- Jdio's Impact Cited cultural state. New Presentation Whether you judge radio effectiveness by coverage pattern, Page 30 audience rating or actual cash register results, you'll find that FREE & the Team leads the parade in every category. PETERS, ñtvC. Two Major Probes \Exclusive National It pays to go first -class when you go into the great Heart of Face New Senate Representatives America market. Get with the KMBC -KFRM Radio Team Page 44 and get real pulling power! See your Free & Peters Colonel for choice availabilities. st SATURE SECTION The KMBC - KFRM Radio TEAM -1 in the ;Begins on Page 35 of KANSAS fir the STATE CITY of KANSAS Heart of America Basic CBS Radio DON DAVIS Vice President JOHN SCHILLING Vice President and General Manager GEORGE HIGGINS Year Vice President and Sally Manager EWSWEEKLY Ir and for tels s )F RADIO AND TV KMBC -TV, the BIG TOP TV JIj,i, Station in the Heart of America sú,\.rw. -

Community Rebranding: a Case Study

COMMUNITY REBRANDING: A CASE STUDY A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State Polytechnic University, Pomona In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science In Hospitality Management By Michelle L. Pecheck Spring 2015 SIGNATURE PAGE PROJECT: COMMUNITY REBRANDING: A CASE STUDY AUTHOR: Michelle L. Pecheck DATE SUBMITTED: Spring 2015 The Collins College of Hospitality Management Dr. Ed Merritt _________________________________________ Project Committee Chair Associate Professor Dr. Margie Jones _________________________________________ Associate Professor Dr. Neha Singh _________________________________________ Director of Graduate Studies Associate Professor ii ABSTRACT Intro: This case study profiles Claremont, a city of approximately 37,000 residents. Since its formation in 1887, it has primarily been known as a college town with a history of citrus production. This case study investigates what components would need to be in place to rebrand or reposition the city as a unique, healthful destination. Case: A resident survey, interviews, and focus groups were used to gather qualitative data about residents’ perceptions of the city’s current brand and potential rebranding. Management & Outcome: Scope of work for the focus city included data gathering from residents, and identification of projects, services, and designations to support marketing of the city as a health/wellness destination. Discussion: Data from surveys, focus groups, and key informant interviews indicated that residents were uncertain of the City’s current brand, in general appeared to care little about the brand, and lacked information about the City’s interest in a possible future rebranding. Further, City documents revealed a history of departmental rebrandings that may have obscured the City’s current brand image. -

Broadcasting Telecasting

YEAR 101RN NOSI1)6 COLLEIih 26TH LIBRARY énoux CITY IOWA BROADCASTING TELECASTING THE BUSINESSWEEKLY OF RADIO AND TELEVISION APRIL 1, 1957 350 PER COPY c < .$'- Ki Ti3dddSIA3N Military zeros in on vhf channels 2 -6 Page 31 e&ol 9 A3I3 It's time to talk money with ASCAP again Page 42 'mars :.IE.iC! I ri Government sues Loew's for block booking Page 46 a2aTioO aFiE$r:i:;ao3 NARTB previews: What's on tap in Chicago Page 79 P N PO NT POW E R GETS BEST R E SULTS Radio Station W -I -T -H "pin point power" is tailor -made to blanket Baltimore's 15 -mile radius at low, low rates -with no waste coverage. W -I -T -H reaches 74% * of all Baltimore homes every week -delivers more listeners per dollar than any competitor. That's why we have twice as many advertisers as any competitor. That's why we're sure to hit the sales "bull's -eye" for you, too. 'Cumulative Pulse Audience Survey Buy Tom Tinsley President R. C. Embry Vice Pres. C O I N I F I I D E I N I C E National Representatives: Select Station Representatives in New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington. Forloe & Co. in Chicago, Seattle, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Dallas, Atlanta. RELAX and PLAY on a Remleee4#01%,/ You fly to Bermuda In less than 4 hours! FACELIFT FOR STATION WHTN-TV rebuilding to keep pace with the increasing importance of Central Ohio Valley . expanding to serve the needs of America's fastest growing industrial area better! Draw on this Powerhouse When OPERATION 'FACELIFT is completed this Spring, Station WNTN -TV's 316,000 watts will pour out of an antenna of Facts for your Slogan: 1000 feet above the average terrain! This means . -

Shuttlegirl Julie Anne Comine Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1998 Shuttlegirl Julie Anne Comine Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Creative Writing Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Comine, Julie Anne, "Shuttlegirl" (1998). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 14435. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/14435 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Shuttlegirl by Julie Anne Comine A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: English (Creative Writing) Major Professor: Neal Bowers Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1998 Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the Master's thesis of Julie Anne Comine has met the thesis requirements ofIowa State University Signatures have been redacted for privacy lU for Jeff, with great impatience IV TABLE OF CONTENTS I. The Astronaut's Bride 1 The married planet 2 Reputation 3 hoopskirt 4 The Godmother, part 3 1/2 7 To the memory of Mrs. Seuss 8 Canticle of tentacles 9 The torch singer who came in from the cold 10 Sarcastics anonymous 11 dada 12 Decree 13 Breaking down is hard to do 16 The book of Sarah 17 Hymns & hers 19 Diadem 20 II.